April 5–July 14, 2024

When the factory at Untere Weißgerberstraße 13 in Vienna was converted into a museum, in keeping with artist and designer Friedensreich Hundertwasser’s colorful and sustainable aesthetic and design principles, straight lines were bent, more light was allowed in, and the façade was adorned with mosaics and pierced with plants. What opened as Museum Hundertwasser in 1991, now KunstHausWien, positions itself as an ecological museum and is the center of an exhibition styling itself as the first “climate biennial.”

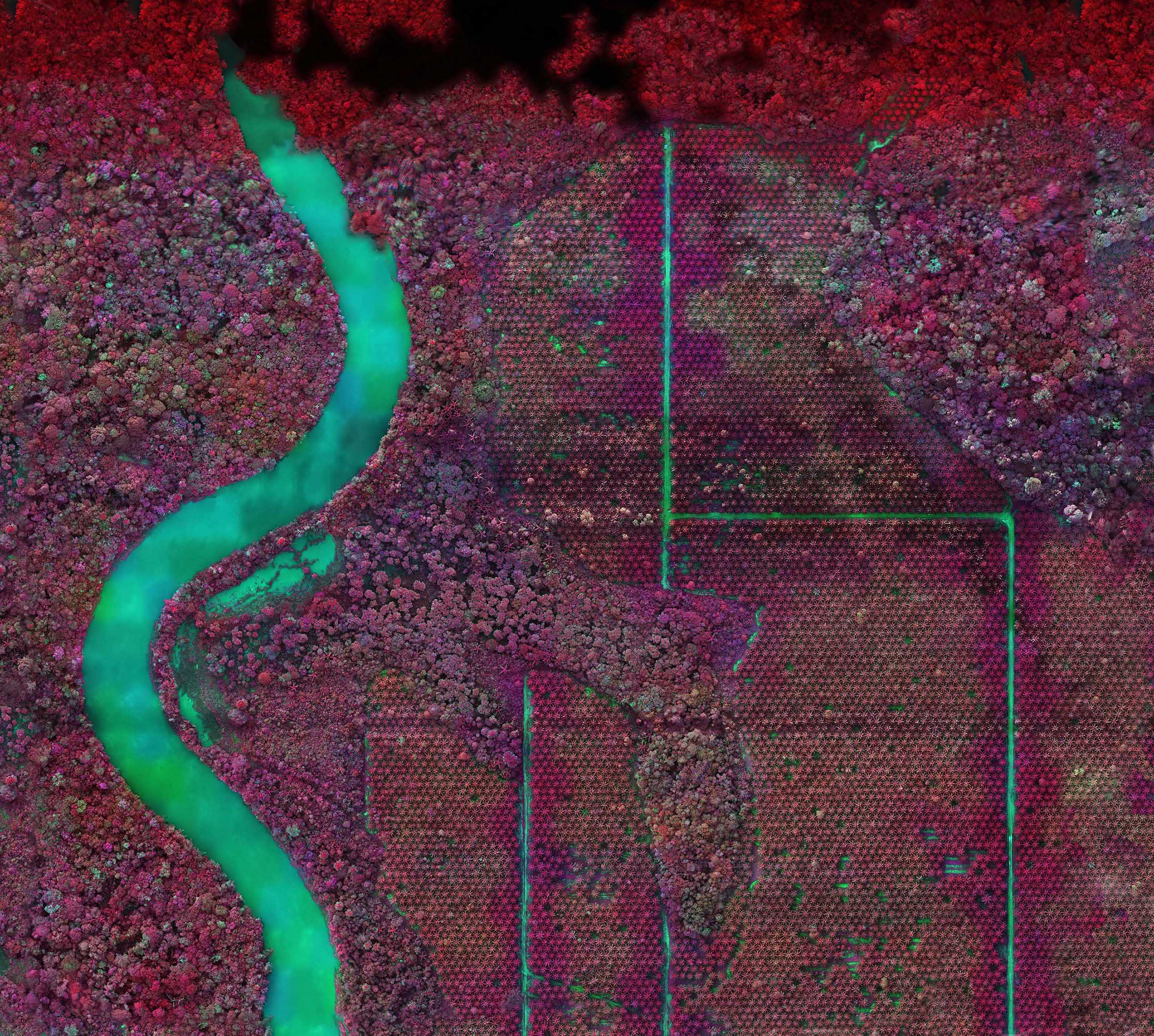

There “Into the Woods,” curated by Sophie Haslinger—one of many programmed or affiliated exhibitions and projects—arranges works by nineteen artists into thematic areas that cover, amongst others, the effects of monoculture, felling and deforestation, and how climate change is impacting forests in a survey of an environment we depend upon yet routinely destroy. Richard Mosse’s multispectral drone-camera shots illustrate deforestation in pointed pinks; Susanne Kriemann’s screenprints reflect on the poetry and exploitation of woods in ink generated from discarded cheap timber furniture; Eline Benjaminsen and Elias Kimaiyo follow the trail of carbon offsetting to land evictions in Kenya in order that trees can be planted for consumers elsewhere (and intrinsic knowledge of the place and its native fauna lost). Information on all of the works is supplemented by cautious scientific crib notes to each chapter authored by local academics. Alongside Diana Scherer’s root tapestries, for example, a text notes how the hypothesis that large trees supply smaller ones with resources through mycorrhizal networks “has so far held up in only a few scientific studies.” This might be edgy scientific language but is low impact for viewers accustomed to artistic speculation.

The second biennial focal point, a former railway site, Festivalareal Nordwestbahnhof, hosts the exhibition “Songs for the Changing Seasons” curated by Filipa Ramos and Lucia Pietroiusti. Works spread their wings in a long, postindustrial space: Eva Fàbregas’s Exudates (2024), large pinkish spheres coated in wrinkled and fleshy latex, might have emerged organically throughout the hall; Cooking Sections’ Salmon: Feed Chains (2022), a long trumpet-like rotating speaker, invites you to walk in circles while listening to the mesmeric yet horrific realities of intensive fish farming: “Fish eat chicken eat fish eat chicken feed feed feed….” Works bleed into each other audibly and visually in a disquieting chorus, so the silence of Adrián Villar Rojas’s The End of Imagination (2021) is striking: webcam footage of animals in sites deserted by recent lockdowns shows them manifestly unperturbed by our absence.

To quote the organizers, the overarching idea of the biennial is to spur “the paradigm shift toward a livable and sustainable future on our planet. The key tools to achieve this objective are, without doubt, participation, collaboration, and awareness.”1 To this end, the programme at the semi-derelict Festivalareal includes an Atelier Luma and Vienna Business Agency project, where architecture students research material reuse, and a showcase for “Design with a Purpose,” objects that try to alter the dynamics of product lifecycles. The same location offers childcare, no-consumption spaces where you can spend time without any pressure to buy anything, and compost toilets; in the yard outside, tarmac has been torn up to create beds in which slender trees and herbs seem to be flourishing—they can enjoy a few years before the site’s eventual redevelopment.

Care is evident across the board: the biennial tries to set an example for making and visiting exhibitions by minimizing shipping, and commissioning projects that are locally informed and realized; where one installation was marred by wrinkled vinyl, the images were not reprinted to save materials, for example. Yet I found myself questioning what role artists have in the whole endeavor. In “Into the Woods,” Rasa Smite and Raitis Smits present a VR installation allowing us to see the “breathing” of trees, i.e. volatile organic compounds in the air we might appreciate as the scent of pine. An accompanying video about their research includes biologists lauding the collaboration with artists, who bring novel viewpoints and new ways of visualizing their work. Is that all there is? What about agitation, instigation, imagination?

More abrasion is to be found further from the biennial’s nuclei. Within the “Immediate Matters” program of exhibitions in off-spaces, at discotec gallery, Kathrin Stumreich records little plumes of smoke in blue skies around a concentrated solar plant in the Mojave Desert. These puffs are unsuspecting birds being incinerated in the immense heat generated when 150,000 mirrors concentrate sunlight on one solar plant. On a grander scale, at Belvedere 21, artist and activist Oliver Ressler makes works in video and still image that illustrate the methods of organized protest, demonstrate self-management in practice, and kibosh the false promises of the carbon capture industry. And in between Ressler posits optimistic future scenarios of the regreened ruins of extractivist capitalism.

At Foto Arsenal, Beate Gütschow, a photography professor at the Academy of Media Arts Cologne, exhibits some of her earlier aesthetically driven investigations. “Hortus Conclusus,” a 2019 series of composite images of park landscapes, is shown alongside an ongoing series of documentary images that record the results of climate change and her participation in environmental protests. Gütschow knows that she is implicated and that her medium is tainted; she wishes to record but not exploit, and struggles to square the circle. “I wonder what role I assume as an artist in activism,” she writes in text that accompanies the images, “this relationship can quickly become extractive, because art takes on value through activist content. After all, it is part of the capitalist commodity and attention economy.” A similar quandary perhaps informs “Into the Woods”: in order not to berate or shock without justification, the exhibition ends up evading confrontation, whereas Gütschow openly acknowledges the impossibility of a fitting artistic response.

Tucked out of the way in the courtyard of the KunstHaus the Hamburg collective Baltic Raw Org’s sci-fi-style ARAPOLIS: climate, displacement, gambling (2024) invites visitors to think through various scenarios and bet on the future. It is at once one of the most engaging and testing elements of the biennial, proposing that visitors discuss and reach consensus before they interact, and one of the most doom-laden, as the scenarios are lightly fictionalized projections of scientific prognoses. Often the answer feels like “none of the above,” provoking some soul-searching. Do we need to reframe our actions, or our conceptual framework? The latter is perhaps a more challenging endeavor, and an interesting counterbalance to the broadly anthropocentric tone of the biennial. Though humanity has catalyzed climate change, we are not in control of its effects.

Quoted on the exhibition website. The emphasis on collaboration means that several projects—notably the Activism Camp outside the Volkskunde Museum that is part of the Wiener Festwochen from 17 May–23 June—operate out of synch with the biennial’s set 100 days.