There is something elusive about the term “design.” English dictionaries tell us the word comes from French, French dictionaries point to an Italian origin (disegno, drawing), but modern Italian uses the English word “design.” French and German have also adopted the English term, while Spanish prefers diseño. Most cultures, it seems, project the idea of design into the sphere of international English and the cool modernity it represents.

In these languages “design” has several meanings that include: plan, trick, and deceit (as in “to have designs”). In French, for instance, the word dessein refers to this kind of cunning: in one of Edgar Allen Poe’s stories, this is the term C. Auguste Dupin inscribes on the purloined letter that inspired Jacques Lacan to write one of his most famous seminars. As Derrida pointed out, Lacan misread dessein as destin, transforming “design” into “destiny” and producing one of the most famous misreadings in the history of literary theory. Design, Derrida argues, was not destined for this epistemological turn.

Design is a slippery term: it cannot be pinned down to a specific origin, to a specific tradition, and when invoked it often leads to Freudian slips. As we will see in the following cases and their missed encounters with design, “design” becomes an especially unstable territory when it overlaps with sex…

Proust

Dessein is a term Marcel Proust used often when relating tales of seduction. In Time Regained, the last volume of À la Recherche du temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time), one of the characters uses it to describe Baron de Charlus’s seemingly boundless appetite for young men (who seem to get progressively younger as the novel progresses). Near the end, a decrepit Charlus—having suffered several strokes that left him blind and bound to a wheelchair—is cared for by his lover Jupien, who explains to the narrator that ill health has not hindered Charlus’s “cunning designs”:

One day … I was returning from one of these supposedly urgent errands, all the faster because I guessed it to have been arranged on purpose [arrangée à dessein], when as I approached the Baron’s room I head a voice saying: “What?” and the Baron reply: “You don’t mean that this has never happened to you before?” I went into the room without knocking, and imagine my terror! The Baron, misled by a voice which was in fact deeper than is usual at that age (remember that at this period he was completely blind and in the old days, as you know, he had always been partial to men who were not quite young), was with a little boy who could not have been ten years old.1

Charlus’s elaborate designs have a singular purpose: to ensure his erotic satisfaction. And it is the perversity of these designs—today they would be associated with child abuse and in most cultures this passage would provoke the ire of the censors—that interests the narrator. Here design refers to the creative mechanisms—and cunning stratagems—deployed to achieve libidinal satisfaction.

Was Charlus’s design successful? It would seem so, since it allowed him to find a sexual partner and to carry the act to completion. But Jupien seems to imply that the adventure concluded with a comic failure, since the Baron made the wrong object choice, in part because of his blindness (there is a blind-spot in his design). This point is ambiguous, however: the object-choice seems inappropriate to Jupien—and to most readers—but Charlus seems perfectly satisfied—even if a bit surprised by the outcome of his adventure. His design had, in any case, a happy ending.

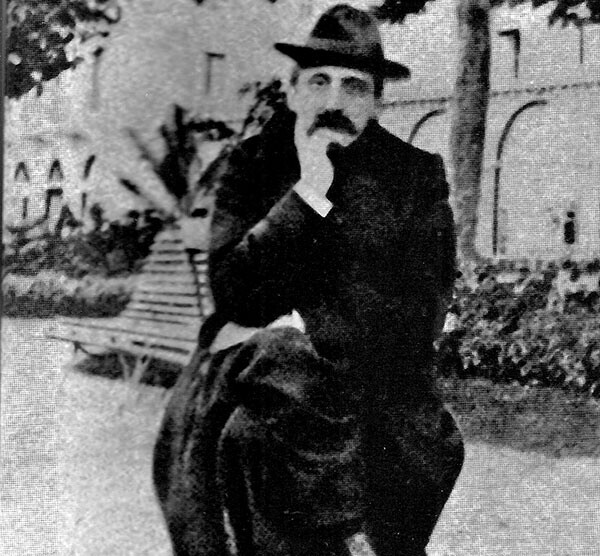

Proust was not what we could call today a design queen. He lived in a dusty apartment filled with the dark, heavy furniture he inherited from his parents. Though he wrote his novel during the heyday of art nouveau—called “modern style” at the time—he had no interest in updating his furnishings or modernizing his living space; visitors recall a dusty and claustrophobic space where the curtains were always drawn and the rooms were airless. Nor was he a label queen: in his youth he spent countless evenings dans le monde, attending dinners and parties and cocktails, but most of his friends recall him as a poorly dressed man, halfway between a clochard and a ghost. In his diary, Jean Cocteau recalls that one day Proust called and asked him to accompany him to the Louvre so he could see Andrea Mantegna’s Saint Sebastian: it was mid-summer but the novelist, pale as a ghost, showed up wearing a fur coat, gloves and a scarf. “No one in the galleries looked at the paintings,” Cocteau writes; “they were too busy looking at Proust.”

Proust is often linked to dandyism, and it is true that many of his friends—like Robert de Montesquiou—and some of his characters—like Charlus and Robert de Saint-Loup—are sharp dressers, but in real-life (and especially in his later years) he seems to have been completely uninterested in either his appearance or the design of his clothes. His unfashionable overcoat has recently been the subject of a book by Lorenza Foschini, Proust’s Overcoat. Could it be that all of Proust’s design energies went into literature and sex?

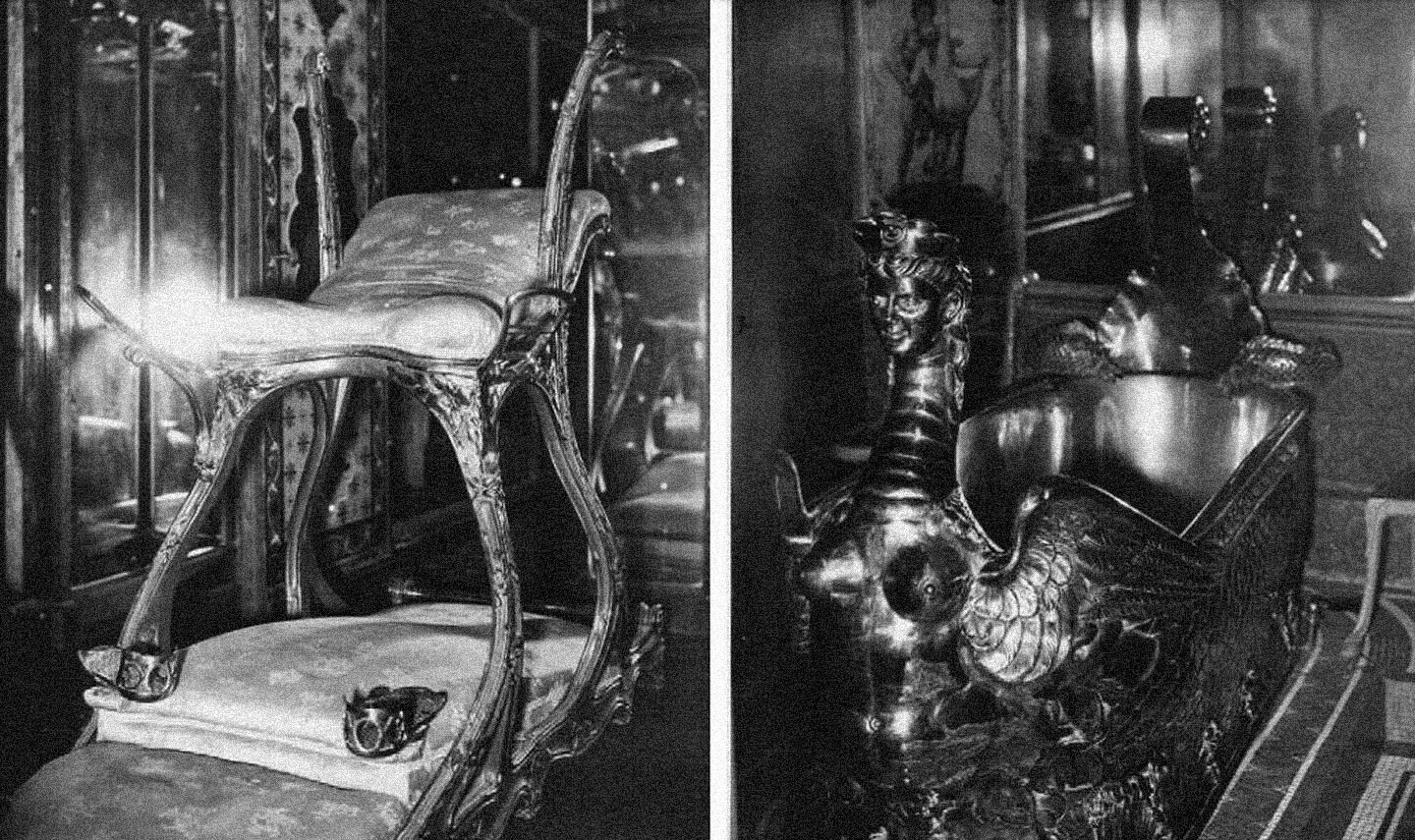

One of the most detailed descriptions of interior design in Proust’s novel appears in the section devoted to Jupien’s male brothel. The living quarters of the Duchesse de Guermantes or Charles Swann are never described in much detail, but the interior of this Temple of Sodom gives rise to pages and pages of information: we learn about the layout of the rooms, the number of stories in the building, and even the design of peep-holes to satisfy shy voyeurs. The model for this heterotopic erotic space was a hotel on the rue de l’Arcade owned by a Breton by the name of Albert LeCuziat. During the belle époque there were so many establishments of this kind in Paris—including the Chabanais, arguably the most famous brothel in the world—that historians could write a history of brothel interior design, which was not only decorative but also functional; one designer had to go as far as to conceive a special piece of furniture to allow the Prince of Wales to enjoy, simultaneously, the erotic pleasures afforded by the bodies of two female companions.

Freud

Though Sigmund Freud and Proust never met, their lives and interest overlapped. Freud, in Vienna, published his Three Essays in the Theory of Sexuality in 1905, while Proust, in Paris, was busy writing his novel. Both were fascinated by the same topics: sexuality, the workings of memory, and the discontents brought about by the demands imposed on us by civilization.

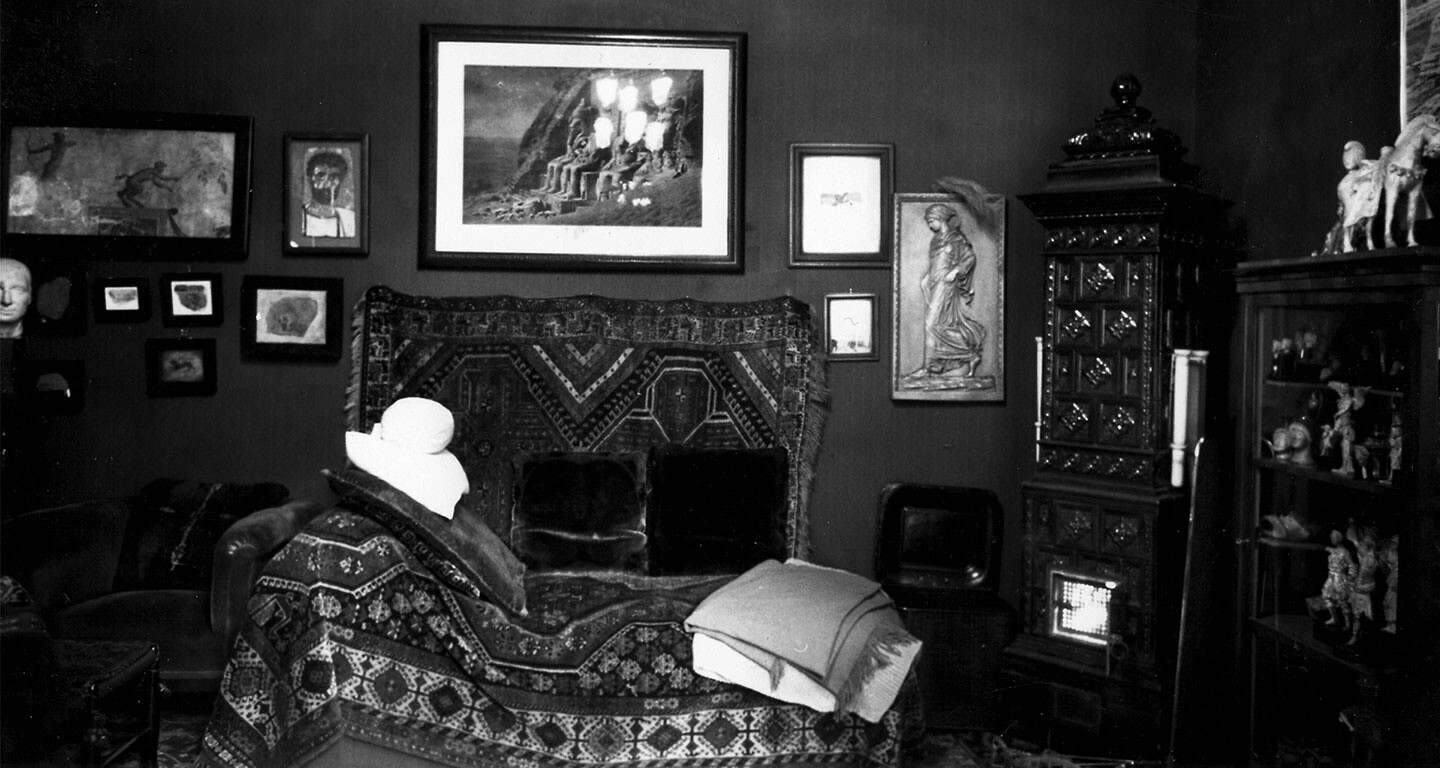

Freud, like Proust, had little interest in either interior or fashion design. Though he overlapped with Adolf Loos, who revolutionized the concept of living space, the analyst continued to live in a stuffy nineteenth-century apartment on Berggasse, furnished with Persian rugs, heavy Biedemaier objects, and thousands of Greco-Roman and Egyptian statuettes. His dress was equally un-modern: in a time marked by dandies and experimental dressers, Freud opted for the most sober and neutral of outfits (in one of his papers on technique, he even recommended that analysts avoid variations in dress from session to session). He was less disheveled than Proust, but equally unfashionable, and could not have been more different than Lacan, who wore designer shirts and dressed the part of the dandy.

Unlike Proust, Freud seems to have been completely uninterested in interior design. Nowhere in his published work does he describe an interior: neither patient’s apartments nor brothels. But he did make one telling comment about design. In the Three Essays he writes:

The progressive concealment of the body which goes along with civilization keeps sexual curiosity awake. This curiosity seeks to complete the sexual object by revealing its hidden parts. It can, however, be diverted (“sublimated”) in the direction of art, if its interest can be shifted away from the genitals on to the shape of the body as a whole.2

This passage is followed by a most intriguing footnote:

There is to my mind no doubt that the concept of “beautiful” has its roots in sexual excitation and that its original meaning was “sexually stimulating” … This is related to the fact that we never regard the genitals themselves, which produce the strongest sexual excitation, as really “beautiful.”3

Freud would have interpreted the aesthetic pleasure generated by well-designed objects as having a sexual origin and being the result of the sublimations introduced by civilization. More surprisingly, however, is the fact that Freud dismissed the genitals as unaesthetic. This comment, which has been analyzed at length by Leo Bersani, reveals that the analyst considered the genitals as poorly designed (they performed a function, but had a disagreeable form), and that in his view all good design (characterized by an agreeable form) originated with a turning away from the genitals: design as an anti-genital turn. Proust too might have shared Freud’s vision of the genitals as ill-designed; his novel includes painstaking accounts of seductions but not a single description of the genitals, male or female.

Grindr and the Posthuman

Technology has introduced the specter of designer sex, a decidedly un-Freudian proposition. Apps like Grindr sell its users the fantasy of designing every aspect of their sexual encounters, from the partner—entered in the form of height, weight, hair color and favorite position—to the site and the duration (nsa or boyfriend material).

Freud might have wondered whether the rise of Grindr introduced new sexual perversions—technological fetishism? Smartphone onanism?—while Proust, germaphobic and bed-ridden, would have welcomed this app with open arms, just like he listened to the opera using the theatrophone, an invention that allowed users to dial into the opera house and listen during performances.

Grindr allows users to upload photos to their profiles: proof that the stats—6’1”, bl/bl, top—correspond to what a potential partner might find upon opening the door. Recently a new website, Lurid Digs, ventured to explore the collateral damage—design accidents—generated by users of this app. While the punctum of profile photos is usually the genital area that Freud deemed unaesthetic, it is possible to examine these images for information on current trends in interior design: users pose, most often in various states of undress, in their living rooms, basements, kitchens, and gardens.

The queer eye deployed by the editors at Lurid Digs flows in the exact opposite direction than the process Freud described as sublimation: instead of moving from the unaesthetic genitals to the beautiful artwork, the lurid gaze progresses from attractive body to squalid interior:

In one caption—“Oh come on dude! At least tidy up a little bit first!”—the viewer does not have access to the model’s genitals, but he can appreciate the mess—strewn clothes, dirty laundry, computer cables—crowding the apartment.

Lurid Digs presents its project in the following terms:

Interior design began with the first cave dwellers. Most likely it was a gay caveman who decided to paint pictures of running bison and other frolicking animals on the rough walls and low ceilings of his abode. Not only were these flourishes artistic and decorative, they also served as a way to feel more comfortable while living in a hole in the earth.

But, my how times have changed. Gone is the stereotypical association of gay men with good interior design. The Internet has shattered the gay style myth forever with its slew of nude amateur self-portraits that clog bandwidth from New York to Sydney and back again. These Feng Shui-challenged souls have proven over and over again that male homosexuals can be just as color uncoordinated, sloppy and nasty as their straight brethren. Yes, the gap between what defines gay and straight is slowly beginning to zipper shut.4

Interestingly, Grindr’s terms-of-service (TOS) do not allow users to post images featuring full frontal nudity. Could it be because they agree with Freud that the genitals are unaesthetic? In any case, the app was design precisely to carry out the kinds of erotic designs that Charlus had in mind when he sent out Jupien on a fake errand.

In the new world order of app design, users are post-sexual beings. Body contact—such a twentieth century notion—has been replaced by one-click, slide and screen taps. Freud once wrote of mechanical excitations: could these touchscreen excitations characterize the design of a new, twenty-first century sexuality? In any case, Proust’s dusty, dark, and stuffy interior—the room of a germaphobic asthmatic—would fit right into the gallery of interior design follies highlighted in Lurid Digs.

Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time, Volume VI: Time Regained. (New York: Random House, 2000), 251–252.

Sigmund Freud, “Three Essays in the Theory of Sexuality,” The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume VI (London: The Hogarth Press, 1953), 155.

Ibid., 156n2.

www.luriddigs.com

Superhumanity is a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.

Category

Subject

Superhumanity, a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, is produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.

All uncaptioned images have remained so as per the author’s request.