Singapore, 2030

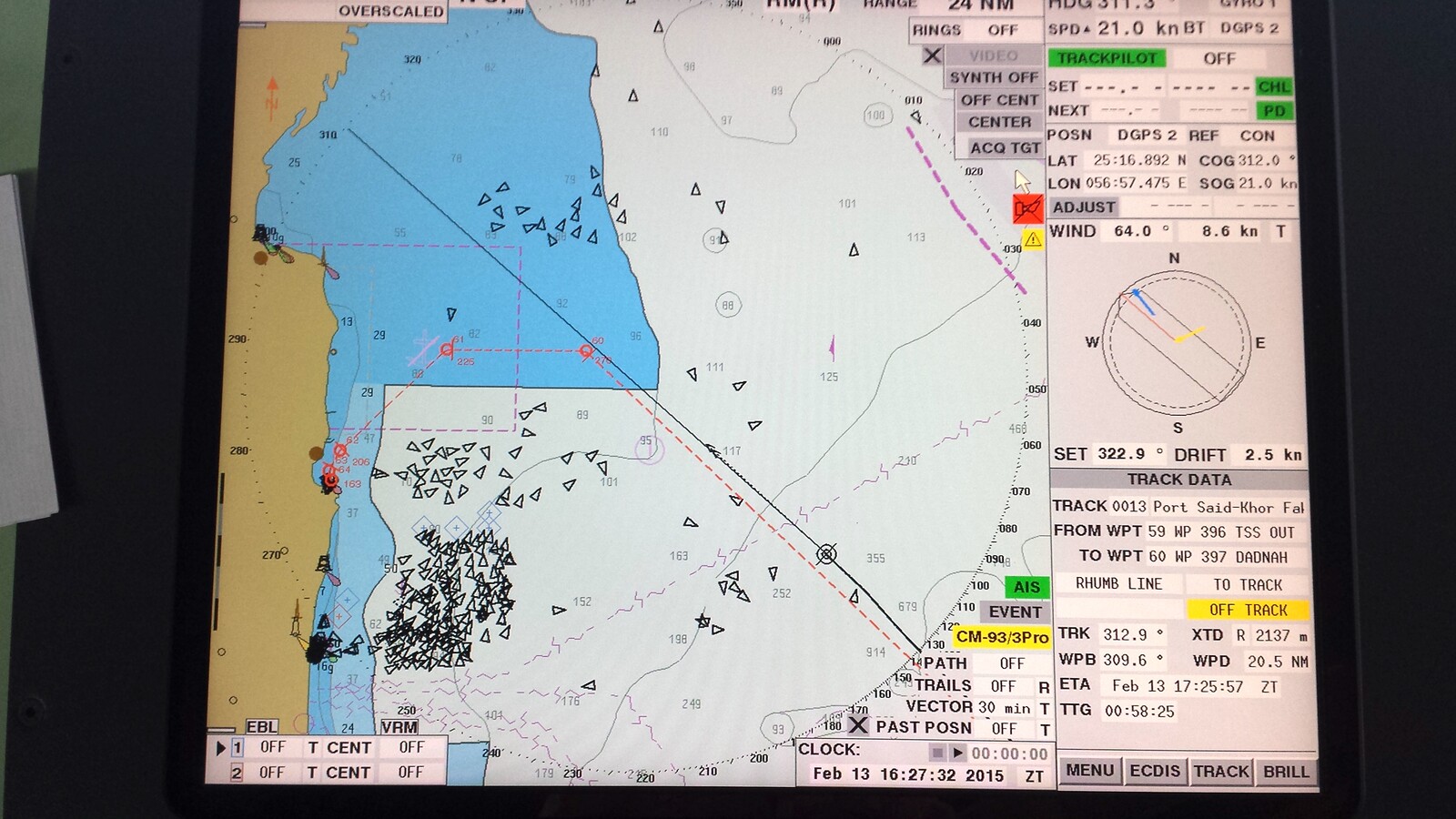

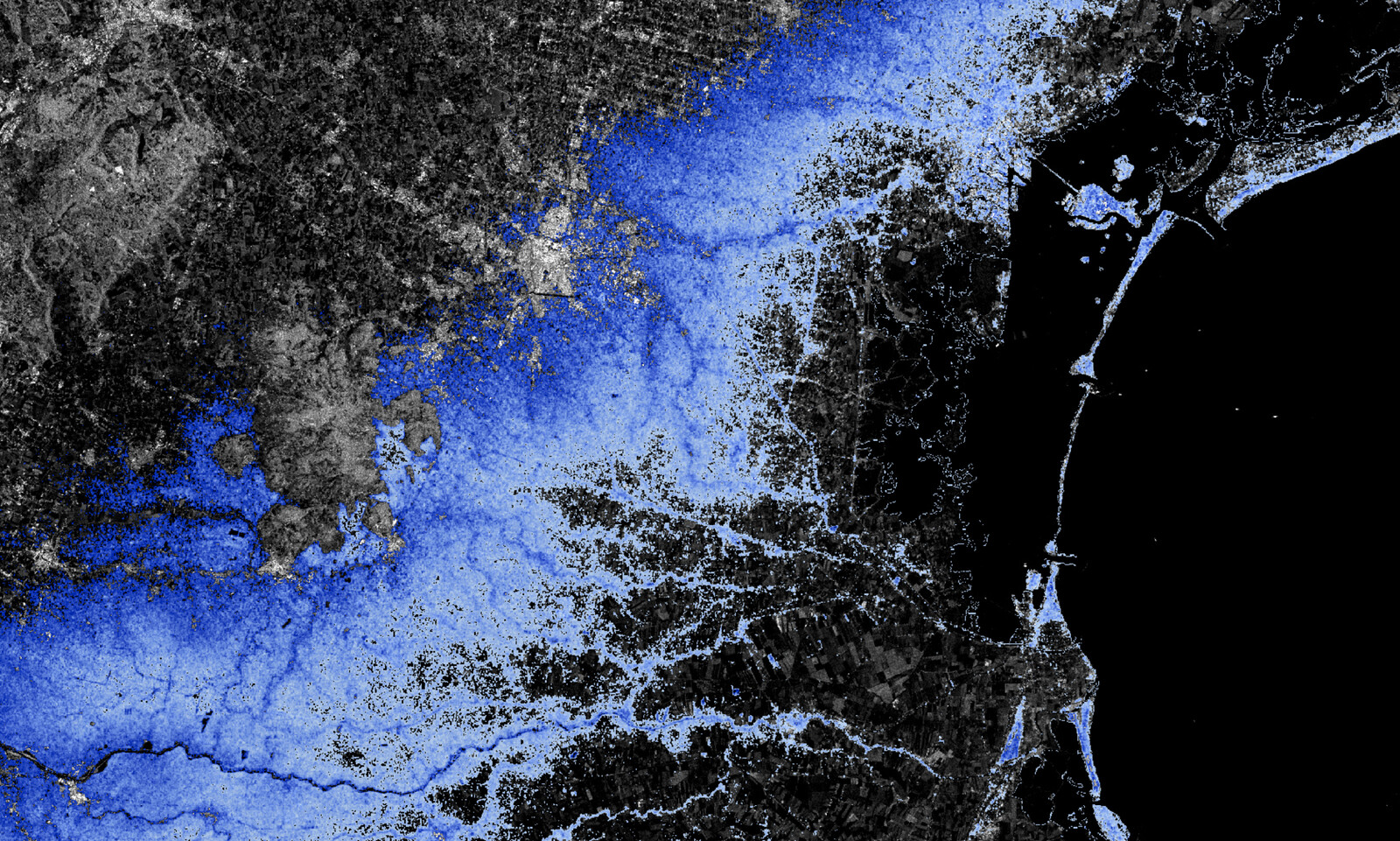

A tropical storm is brewing. A group of anonymous hackers recently leaked confidential government documents showing that Singaporean authorities have been doing business with the notorious Southeast Asian sand cartels for years. Employing forced labor and organized violence, these highly structured criminal organizations are major players in the black sand market, trafficking sand sourced from across the whole of Southeast Asia. They steal entire beaches, dredge paradisal islands, slaughter wildlife, and endanger local communities. Amidst the global shortage of sand—a non-renewable resource—sand gangs have become a profitable business model.

The leaked documents aren’t a surprise to most. After all, once Singapore’s major sand suppliers (Vietnam, Cambodia, Malaysia) banned sand export one after another in the 2010s, how could its “strategic reserve,” those mountainous stockpiles of sand at the edges of the city, keep growing? America hoards oil, China hoards pork, Singapore hoards sand. It’s all vital to their security.

The body of the island-nation is growing. It needs to grow. It will always have a voracious need for concrete, glass, and asphalt as the building blocks of its flesh. Land reclamation has grown the island from 580 square kilometers in the 1960s to around 800 square kilometers today. Things slowed down after the sand ban, but growth has continued nonetheless. Reclaiming sand from adjacent Southeast Asian countries to grow… Sovereign cannibalism at its best. The rich eat the poor.

At the core of the city-state’s operation has always been a colossally complex and unapologetically technocratic risk management system. It is diplomatically nimble and leverages markets with masterful planning, concentrating the flows of capital, resources, and talent to expand its influence beyond its size. It has long been celebrated by international observers for its ability to navigate turbulence while delivering security and prosperity, regardless of how “democratic” its methods are.

In the 1940s, American scholars advocated the so-called “garrison state”—a form of elite government led by the military-industrial complex, with a mindset of perpetual preparedness for war. Singapore was built upon a similar philosophy, though on a much smaller scale: its enemy can be anything that threatens to compromise its survival or prosperity, such as the sand ban, or the slowly rising sea.

Days after the leak, however, the documents haven’t stirred up much controversy. Some fifteen years ago, we witnessed a global populist uprising, after which the frivolous and unstable nature of populist politics crippled many nations, especially their ability to respond to contingency and crisis. In response, Singaporean authorities resorted to a full-on survivalist technocracy, and their approval ratings remain stable. When the sea’s gradual encroachment is shrinking the territories of half the world’s nations, there’s nothing wrong with wanting your own to be among the last standing.

Shanghai, 2050

Underwater tours have become the city’s latest obsession, and one of the most popular destinations is a submerged hotel in Songjiang, a southwestern suburb of Shanghai. The hotel, a luxury establishment, opened thirty years ago. It was built inside a long-abandoned quarry, and was technically the world’s first underground luxury hotel, although many more have drowned since its demise.

In the 1950s, when the quarry started, it was a small hill called Mt. Tianma (“Pegasus”), bulging out of the extremely flat alluvial plain of the Yangtze River Delta. Not far from the quarry, that same decade, farmers uncovered the remains of an ancient irrigation system—later identified as built by our neolithic ancestors some five thousand years ago. Perhaps people living here have always been sedentary, agrarian, and fond of paddy rice.

The efforts and organization of those long-ago people were surely extraordinary. This may even be where complex societies and states originated! But now, with groundwater flooding driven by sea level rise, these ancient endeavors appear kind of comical. The water is too much now. The groundwater level rises faster than predicted. Fortunately, at least, the water that emerges is so pure and clear. It feels familiar. Visitors can get to know these relics of other times—the irrigation system and the hotel—through this aquatic mediation. So it goes.

The socialist state eventually chiseled Mt. Tianma Quarry into Tianma Pit. Its mainstay was andesite, a volcanic stone good for construction and roads. By the year 2000, when it was abandoned, the pit was seventy meters deep and covered an area of thirty-seven hectares. A natural spring, coupled with the ample rainfall of southern China, had turned it into a steep turquoise pool with sublime perpendicular cliffs. If viewed from midair, the pit would probably have appeared half like a scar in the land, and half like a piece of jewelry.

After a dozen years and $300 million spent, mostly governmental subsidies, a twenty-one-story luxury hotel was finally erected from the base of the pit. It was awkwardly named InterContinental Shanghai Wonderland, owned by the British multinational hotel company IHG. But locals simply called it the Tianma Pit Hotel. Government officials were excited to see a socialist industrial ruin become a neoliberal architectural marvel. They wanted it to be positive proof that the Reform could undo mistakes made in the socialist past. The project made a splash in architecture and tourist magazines, its planners and architects lauded for their Midas touch.

When inaugurated in 2018, the topmost two floors—also, incidentally, the only two floors above ground—comprised the presidential suite, with an unhindered panoramic view. The bottommost two floors, submerged in the azure-green pool, were an underwater restaurant. In between were four hundred rooms with plant-decorated balconies, all facing the high drop waterfall on the opposing cliff. Now all this fanciness is gone, or rather, it’s still there, but can only be witnessed on a tour, as a kind of curiosity. Tours start from the presidential suite; it’s still the only portion above, just water this time. Slowly descending through a transparent medium, into a scene once well documented is truly a breathtaking experience. Everything is tinted emerald.

The agency offering the tour started their business giving underwater tours of Fengdu, the city submerged by the Three Gorges Dam in 2003. The colossal dam tamed the fierce Yangtze River, turning it into a giant bathtub of bubbly water queuing up to actuate its turbines and generate electricity. A million people were uprooted and relocated to planned residential areas on higher ground.

In Taoist mythology, Fengdu was the netherworld, the home of the dead. For centuries, it had been an eerie attraction among boat trippers downstreaming the Yangtze; a traveling route which inspired more poems and prose than all the rest of China put together. Shrines and temples dedicated to the afterlife were built on the Ming Mountain of Fengdu and were regularly visited by worshippers. In those sites of rituals, there used to be grisly ancient sculptures depicting torture scenes in hell, trying to morally instill a draconian feudal order.

The agency no longer offers its tour of Fengdu, since it’s perilous to operate and the structures have all been washed away anyway. But they are expanding their business along the coast to cover all the lovely places sitting underwater. It certainly will be a lucrative business. With the old coastal economy destroyed by groundwater inundation, turning drowned places into sites of attraction is the next big thing.

Hong Kong, 2098

By the end of the century, 90% of what we used to know as Hong Kong has become submerged and no longer inhabitable. Most of the remaining population occupies three megastructures—Wing Sung Tower (the Tower of Eternal Life), Wing Sai Tower (the Tower of Aeon) and Wing Gau Tower (the Tower of Permanence)—located respectively on Tai Mo Shan, Lantau Peak, and Sunset Peak, the three highest peaks in the city. Those born after 2072—the year the deadliest typhoon in recorded history wreaked havoc on the seawalls—have never set foot outside the towers. According to those who survived, the water that flooded Hong Kong and many other parts of the Greater Bay Area after the storm of ’72 is foul, putrid, and mixed with enormous chunks of marine debris, some large as islets themselves. Anyone who touches it dies within days.

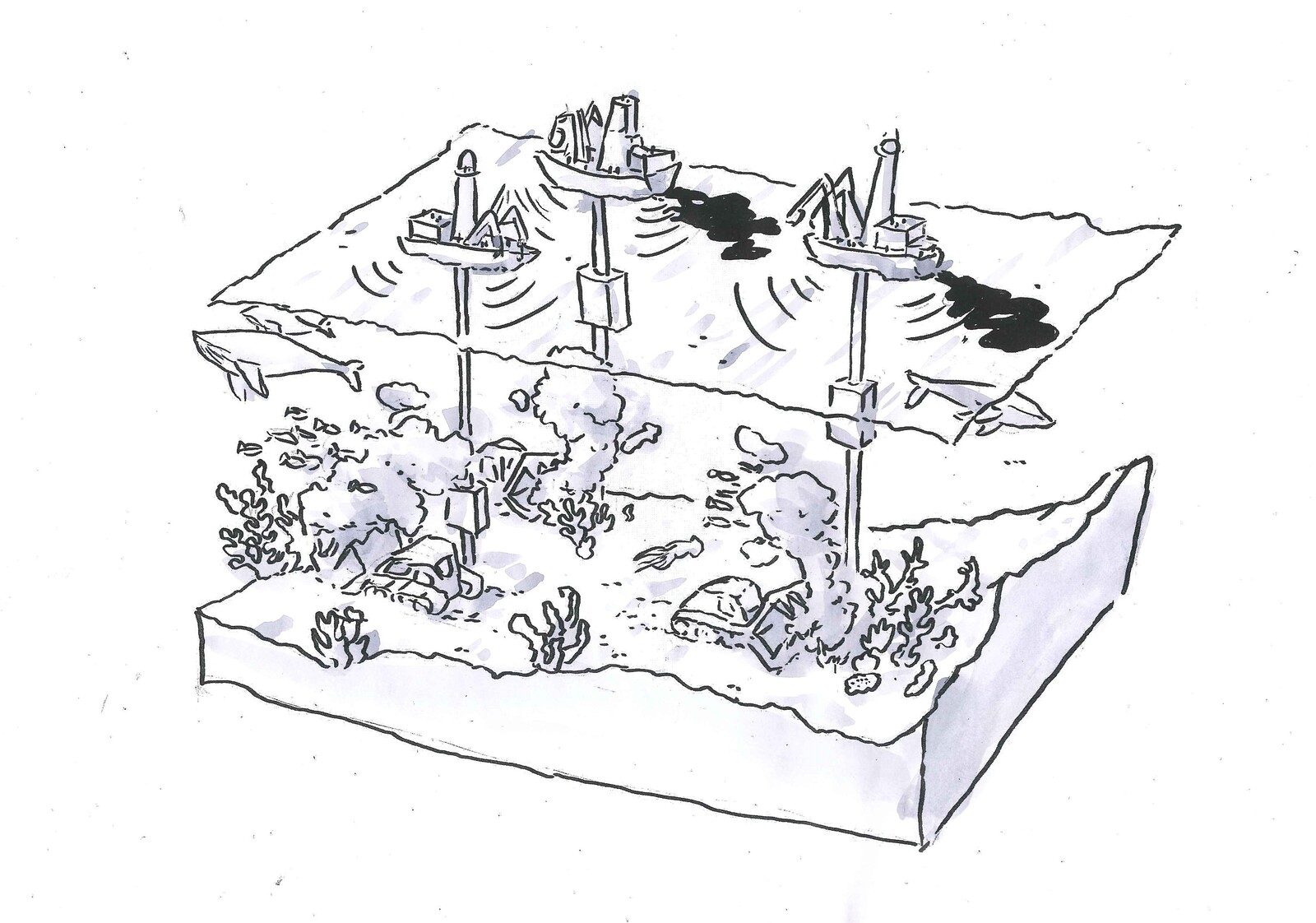

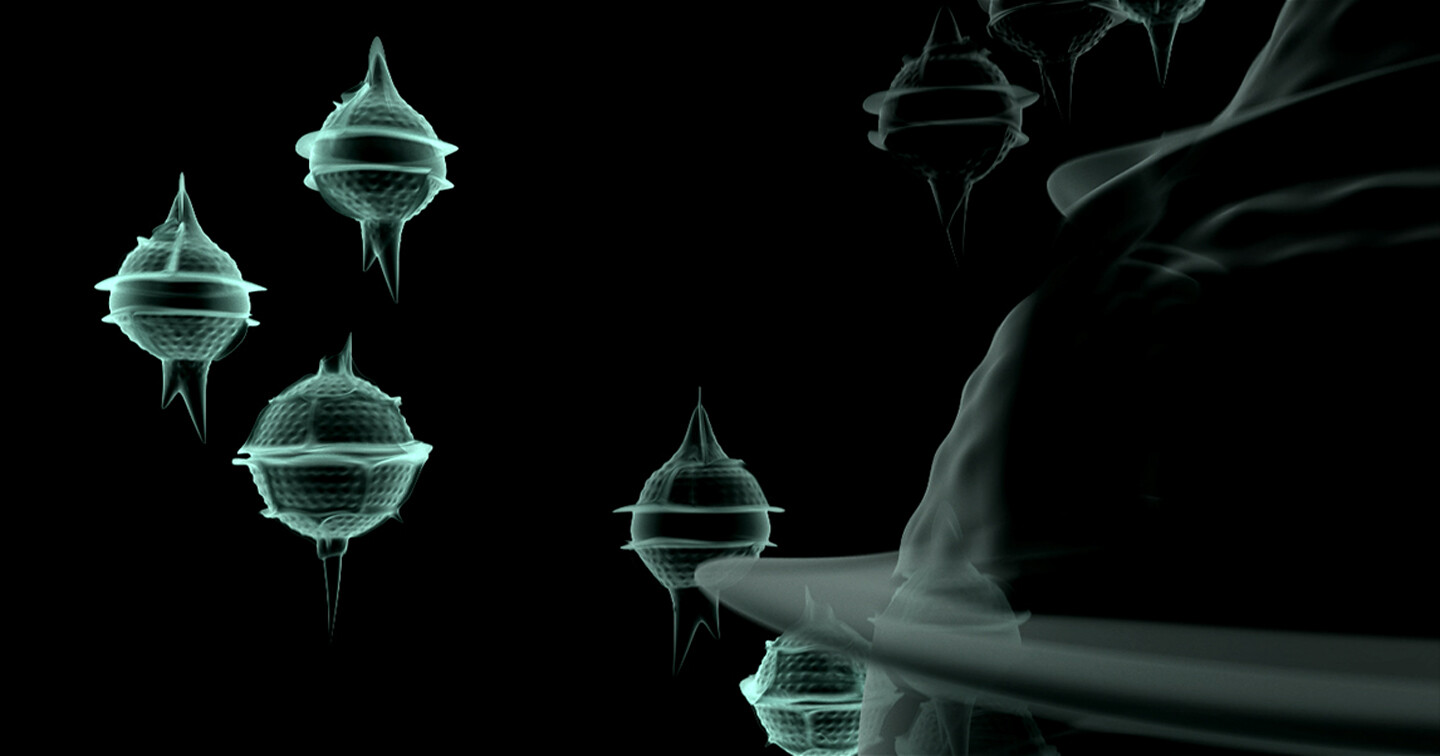

Forty percent of the population was wiped out, and many of the survivors fled the city. Scientists haven’t been able to figure out exactly what is wrong with the water—the decomposition of the microplastics in the North Pacific Trash Vortex, however severe, should not have such lethal consequences. A reigning hypothesis is that excessive deep-sea mining activity caused the release of an unknown substance (or, some believe, a sea spirit) from the bottom of the ocean nearby. Over twenty years have passed, and no solution has been found. Only androids can survive the corrosive liquid outside, but even their metallic bodies degrade after a few months of exposure.

Completed in the late 2070s and early 2080s, Wing Sung, Wing Sai, and Wing Gao are tree-like buildings over 2,000 meters tall, each playing the multiple roles of residential complex, financial center, transportation hub, and all-purpose vertical locus. The three towers are connected by highways at multiple levels and divided vertically into zones. First 500 meters of the tower is the slum, where roughly 80% of the remaining population resides. Above that are the central business districts and the public zones. The top 200 meters is an exclusive, private zone reserved for luxury condos and penthouses. Only technocrats and uber-wealthy, like the Four Big Families, live there.

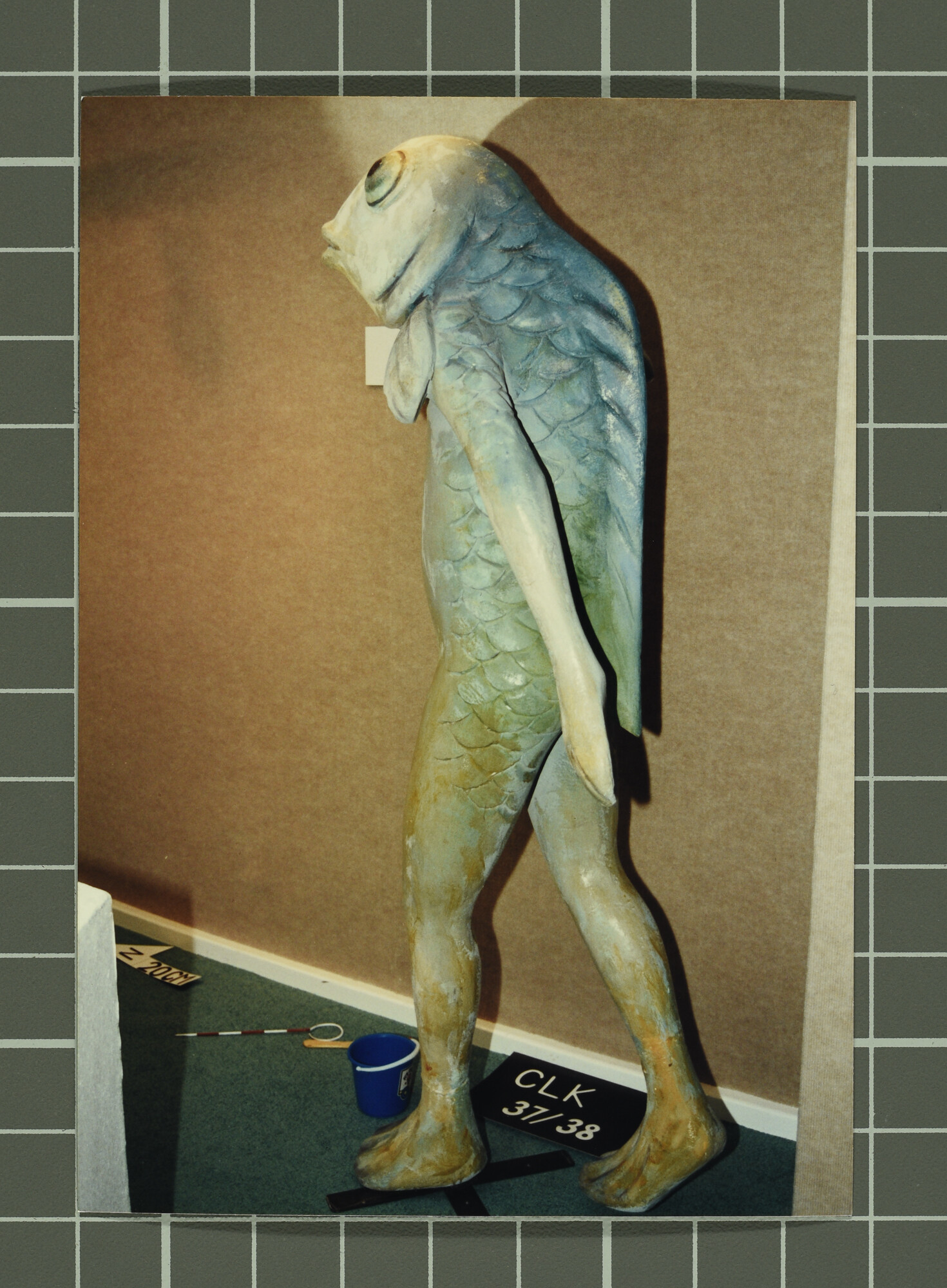

Photographs from the exhibition “Hong Kong Reincarnated: New Lo Ting Archeological Find,” curated by Oscar Ho, 1998. Photo: HA Bikchuen. Source: Ha Bik Chuen Archive. Courtesy of the Ha Family and Asia Art Archive.

Photographs from the exhibition “Hong Kong Reincarnated: New Lo Ting Archeological Find,” curated by Oscar Ho, 1998. Photo: HA Bikchuen. Source: Ha Bik Chuen Archive. Courtesy of the Ha Family and Asia Art Archive.

After the Great Flood, rising anti-government sentiment blamed the government’s technocratic planning and collusion with fracking capitalists for the loss of their sea, which had always been so integral to Hong Kong’s identity. The public campaign took as its mascot the half-man, half-fish creature Lo Ting. According to the New Narratives of Guangdong, written by the Qing scholar Qu Dajun over four hundred years ago, the Lo Ting had once led ungoverned lives in the sea around the Lantau Island area. Legend has it that the people of Hong Kong are their descendants.

In the wake of widespread unrest, the government decided to censor the myth of Lo Ting and attempted to erase all records of it—in literature, in the press, in art—once and for all. Fortunately, a researcher at the Asia Art Archive had managed to make a copy of the photographic documentation from an exhibition titled “Hong Kong Reincarnated: New Lo Ting Archeological Find” before it was confiscated. Mounted in 1998, the year after Hong Kong was handed over from British colonial rule to become a special administrative region of China, the exhibition had brought together relics, maps, documents, and photographs by contemporary artists to present an archeological survey about the Lo Ting settlements. Even before the Great Flood, this once-half-forgotten figure had become the symbol of the city’s solidarity.

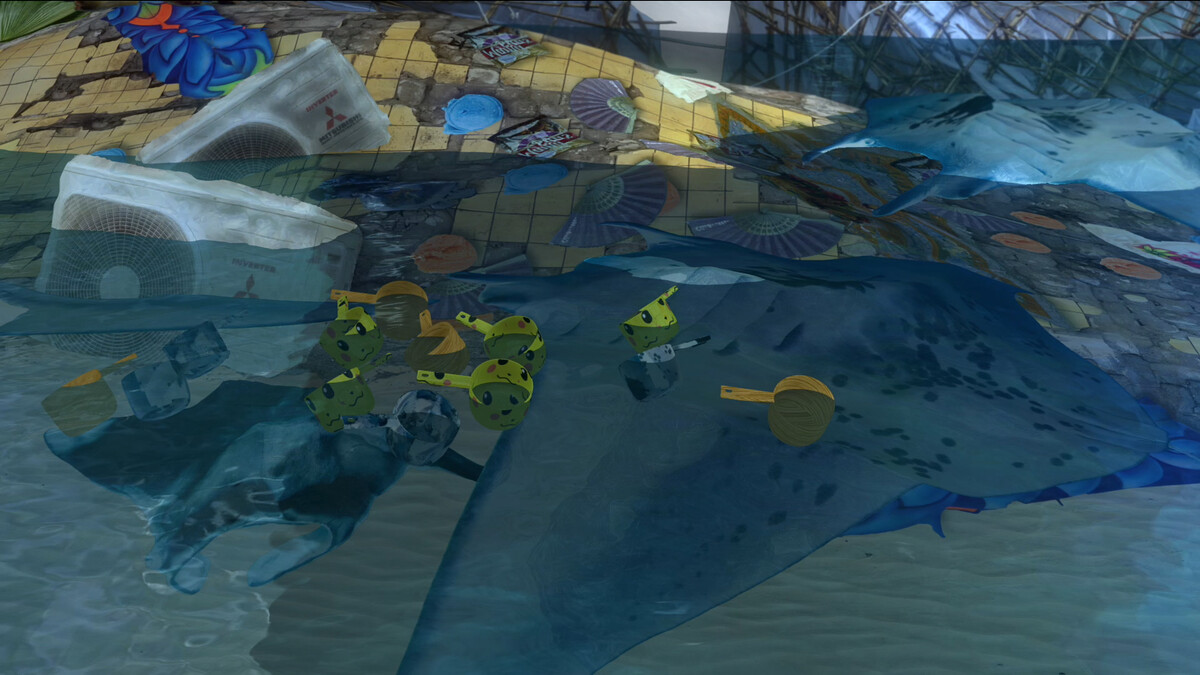

Even though their real home had been changed beyond recognition, to preserve this alternative, mythical Hong Kong, some programmers designed an online game set in a present-day virtual model of Hong Kong, with the exception of the Hong Kong Arts Centre (restored to its 1998 condition, thanks to the photos), to keep the Lo Ting exhibition permanently on display. Every July 1, the citizens of Hong Kong log into the game (though it has been repeatedly shut down by the government, they always find a way to relaunch it), where everyone’s avatar is half-man, half-fish. Together, they swim through the waters to the Arts Centre, picking up the remaining chunks of garbage on the way while singing spells to bless the beloved land beneath. They linger for hours, savoring every bit of the past while pondering a future when they will again swim in the sea.

Tianjin, 2070

As it turned out, wiping out the entire species of starry sky beetles was a terrible idea. Only the ocean can stop the viral spread of poplar now.

In 1978, almost a century ago, the same year the far-reaching Reform and Opening-Up policies began, China undertook the Three-North Shelter Forest project. It was a large array of human-planted windbreaker forest belts in northern China, designed to hold back the expanding Gobi Desert and shelter the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei megalopolis, home to a population of 110 million at the time, from increasingly devastating sandstorms. Choking air quality in dusty springtime was politicized. Party officials viewed sandstorms as a threat to social stability because it infringed on the basic rights to health of the booming urban middle class.

In World War I, chlorine gas viciously broke the stalemate of trench warfare and re-galvanize combat. Sandstorms in late twentieth-century China could similarly tip the unstable consensus between the party-state and its people: they were willing to exchange political representation for an ever-growing economy, but only provisionally. The wind carried toxic gas agents and sand particles alike. The party-state had to declare war on sandstorms blown from the north.

The Gobi Desert spans Northern China and Southern Mongolia. The southern edge of this desert was historically the interface between the agrarian Han people and the nomadic non-Hans roaming in the northern prairies. Tensions between their two fundamentally different ways of human life have shaped the history of Northeast Asia for the past millennia. The perpetual anxiety and discontent of the Han Chinese empires externalized itself in the long history of state-led afforestation along the historical frontier of the Great Wall, often carried out by empire soldiers.

In the moralistic universe of ancient Chinese historiographers, history exhibits a cyclic pattern. This influential Dynastic Cycle theory depicts the rise, fall, and eventual substitution of dynasties, subject to the Mandate of Heaven (天命). The Mandate of Heaven often manifests itself in the form of climate: genial and cultivating in a dynasty’s nascence; punitive and ruthless after it reached its apex and turned degenerate.

Could the Dynastic Cycle manifest itself in the disenchanted modern world as a self-fulfilling prophecy? Out of self-preservation, then, in 1978, the party-state decided to break the cycle and secure its longevity. In case it falls out of favor with the Mandate of Heaven, its technocratic weaponry may still have a chance against the weather, the executor of the Mandate.

The Three-North Shelter Forest is an extreme monoculture of poplar trees, which are known for their rapid growth and ability to be used as timber. From the very beginning, however, the windbreaker forest had been infected with Asian long-horned beetles, or as the locals call them, starry sky beetles. Up until the 2010s, one out of three poplars died because of them.

The climate crisis worsened the sandstorms coming from the north, which meant that the Three-North had to grow even denser and larger. Spanning a total area of four million square kilometers, the windbreaker forest was too sparse for pesticides and conventional pest controls to take effect. In the 2030s, then, the government approved genetic modification of starry sky beetles, which worked like a charm. Saboteur genetics from the male beetles would kill any female offspring resulting from mating, and over time shrink the swarms. Since then, the Three-North has been incredibly successful. Sandstorms previously wreaking havoc in the whole Northeast Asia climate region died out.

In the 2050s, the monolithic poplar forest started to go rogue. The single-species forest spread like a viral disease across northern China, strangling all other plants and destroying the habitat for most animals. After destroying the capital, the monoculture forest eventually encompassed and besieged the harbor city of Tianjin. Most of the region’s population fled to the south, and those who remained are stuck in a permanent war against the expanding forest. The trees, designed to demarcate the boundary between culture and nature, civilization and wilderness, prevented the spread of desert, but at the end of the day, became the new desert instead.

Oceans in Transformation is a collaboration between TBA21–Academy and e-flux Architecture within the context of the eponymous exhibition at Ocean Space in Venice by Territorial Agency and its manifestation on Ocean Archive.

Category

This essay grew out of the authors’ ongoing research into the history and politics of terraforming in Asia, in preparation for their exhibition project “Liquid Ground,” which was selected by Para Site, Hong Kong from their 2020 emerging curators open call and is scheduled to open in fall 2021.

Oceans in Transformation is a collaboration between TBA21–Academy and e-flux Architecture within the context of the eponymous exhibition at Ocean Space in Venice by Territorial Agency and its manifestation on Ocean Archive.