The interface between land and water is nature’s metabolic process. In this messy, everchanging, and unpredictable zone, different kinds of porosities emerge and become the birthplace of many more-than-human livelihoods. Water channels are nature’s blood vessel network. The exchange of nutrients and oxygen in our blood flow sustain our lives in the same way that the exchange of water flows shapes different salinity and nutrient zones for vast ecosystems.

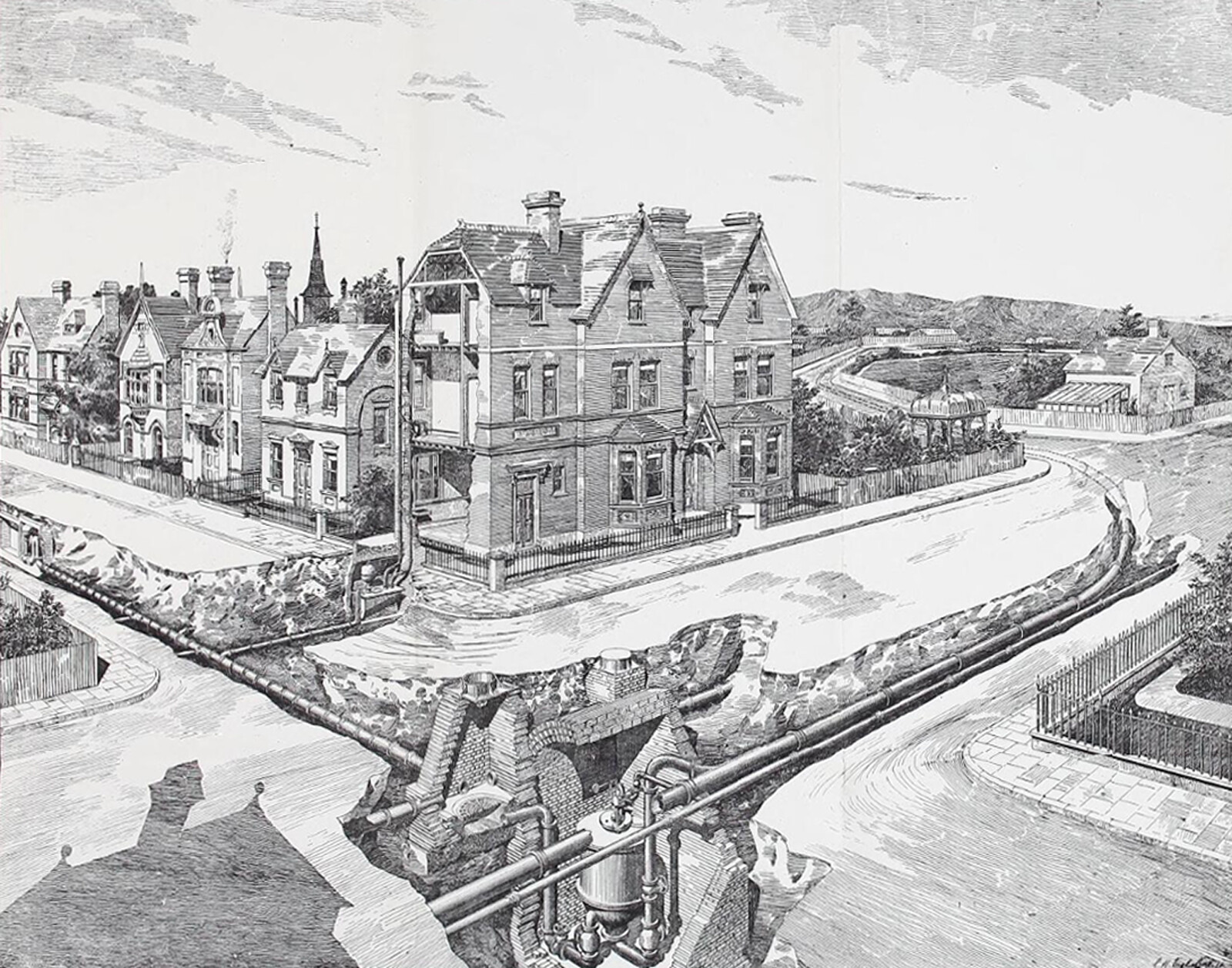

However, increasing anthropogenic modifications to coastal land-and-seascapes proliferates other kinds of porosities that impose threats to nature’s once vigorous metabolism. Where some coastal infrastructures block the exchange of water, others encouraged the fast mixing and exchange of toxins through industrial and agricultural dumping, exceeding nature’s affordance to digest. According to Pak Sothi, Orang Seletar elder from Kampong Pasir Salam:

In Johor’s history, there was a period of rain. Not tsunami, but rain. It rained in Johor for a month; it didn’t matter night or day, the rain did not stop. In just four days, Kota Tinggi was submerged. Just four days, not even a month. Many kaum [tribes/clans] of Orang Asli sat on boats. People were berangkai [joined] together at Gunung Pulai, very joined [puts two curved index fingers together in a linking motion]. [They] could not get close to land because of animals—crocodiles, snakes, tiger, all on the mountain tops. Everyone lived on the boats joined to each other, using rattan to make these joints. When the rain stopped and the tide receded, the joints broke [places two fists in front of his face and then opened his fists with palms forward as he moves his hands swiftly down to either side of his waist]. Orang Asli settled all over the place, that’s why people say [we are scattered] across seven rivers, seven mountains. That’s the story my mother told me when she was still alive: Orang Asli everywhere are our relatives who were once joined together at Pulai when Johor sank. All the Orang know… All their history comes from Johor, Pulau Ubin, Pulau Ketam. When they live on land, their language changed, even though their language was originally Seletar, they mixed with other kaum. This history stretches to Pulau Ketam, to Bukit Kemandul.

—Pak Sothi, Orang Seletar elder from Kampong Pasir Salam1

The Orang Seletar are the indigenous group of people from the Strait of Johor—a narrow channel divides Malaysia with Singapore—who lived within the extreme porosity of the land and waterscapes. Traditionally living on houseboats, the Orang Seletar based their culture and livelihood on the intertwined waterways and mangrove forests. Some survivors from the sinking of Johor used to secure their boats with rattan to the coastal mangrove trees, who became the “sea people.” According to various folk tales, Orang Seletar culture was nurtured by rich, amphibious ecosystems, primarily mangroves. Multiple species see mangroves as their host, such as snakehead fish (Ikan Haruan), mullet (Ikan belanak), parrotfish (Ikan Bayan / Ikan Ketarap), green mussels (Kupang hijau), Melon conch (Siput unam), as well as mud crabs (Ketam bangkang/Yok Sang) and saltwater crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus). As the host of a rich amphibious ecosystem, mangroves supply nutrients, food resources, and materials for more-than-human livelihood and architecture.

The dynamics of porosity shifted when plantations re-shaped the landscapes of Johor. In the mid-nineteenth century, gambier extract was discovered to be a tanning product for leather. Gambier plantations quickly came to dominate the Strait’s near-water regions, where mangroves used to thrive. In plantations, pepper and gambier plants were usually planted together, as they share a symbiotic relationship and tend to grow entwined. The remains of gambier leaves act as nutrients or fertilizers for pepper plants while protecting the pepper plant roots. The gambier extraction process requires the boiling its leaves, and the planters turned to mangrove trees as resources of firewood and charcoal. Gambier cultivation is extremely resource-intensive too; the land was typically exhausted to wastelands within fifteen to twenty years. Following the gambier boom and continuing today, interior and coastal forests have undergone massive deforestation to make way for plantations supplying global demands for commodities like rubber, palm, and pineapple. With the disappearance of mangrove forests as multispecies shelters and nurseries, the Orang Seletar were forced to seek livelihoods elsewhere.

Porosities today have become toxic and dangerous. Coastal infrastructure projects such as land reclamation, dams, and seawalls block water exchange in some places, while exacerbating the mixing of chemical and physical dumps in others. With the intensification of industrial fishing and mussel cultivation, the Orang Seletar find it challenging to maintain their traditional livelihood practices of fishing, hunting, and foraging sustained by the once-abundant ecological zones. With limited access, they largely rely on local Chinese or Malay middlemen to sell their daily catches to urban restaurants and markets. In this extractive landscape, both humans and nonhumans struggle to adapt to this constantly shifting porosity.

From an interview conducted by Zahirah Suhaimi and recorded by Jefree Salim.

Digestion is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the 2022 Tallinn Architecture Biennale, supported by the Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia (IAAC), the Estonian Museum of Architecture, and Friendship Products.