Yuk Hui Read Bio Collapse

Yuk Hui is Professor of Philosophy at Erasmus University Rotterdam, where he holds the Chair of Human Conditions. He is the author of several monographs that have been translated into a dozen languages, including On the Existence of Digital Objects (2016), The Question Concerning Technology in China: An Essay in Cosmotechnics (2016), Recursivity and Contingency (2019), Art and Cosmotechnics (2021), and Machine and Sovereignty (forthcoming 2024). He is the convenor of the Research Network for Philosophy and Technology and has been a juror for the Berggruen Prize for Philosophy and Culture since 2020.

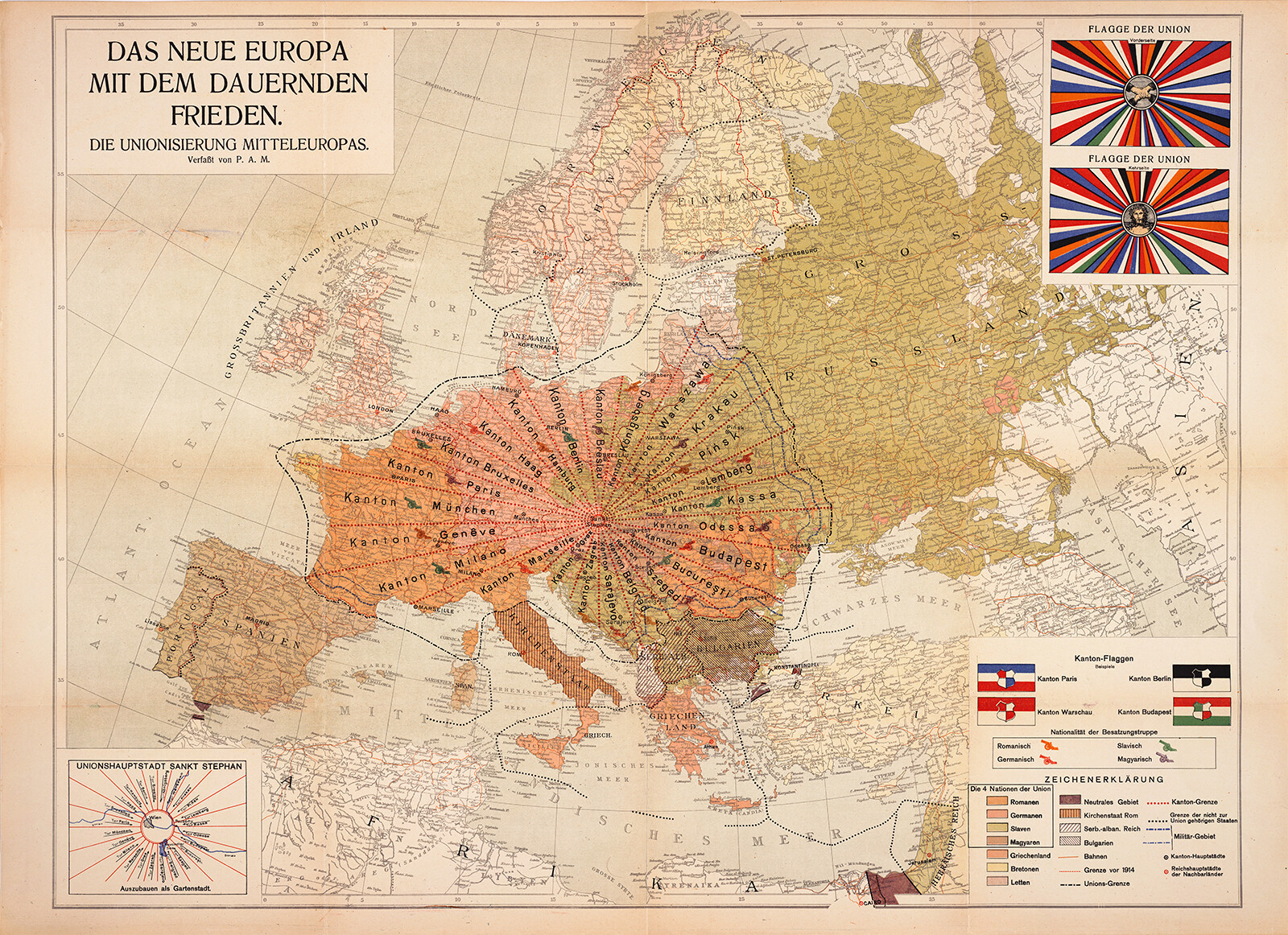

In past centuries, almost every philosopher was addressed according to nationality, and a new school of thought was often prefixed with a nationality. A thinker can only go beyond the nation-state by becoming heimatlos, that is to say, by looking at the world from the standpoint of not being at home. This doesn’t mean that one must refrain from talking or thinking about a particular place or a culture; on the contrary, one must confront it and access it from the perspective of a planetary future.

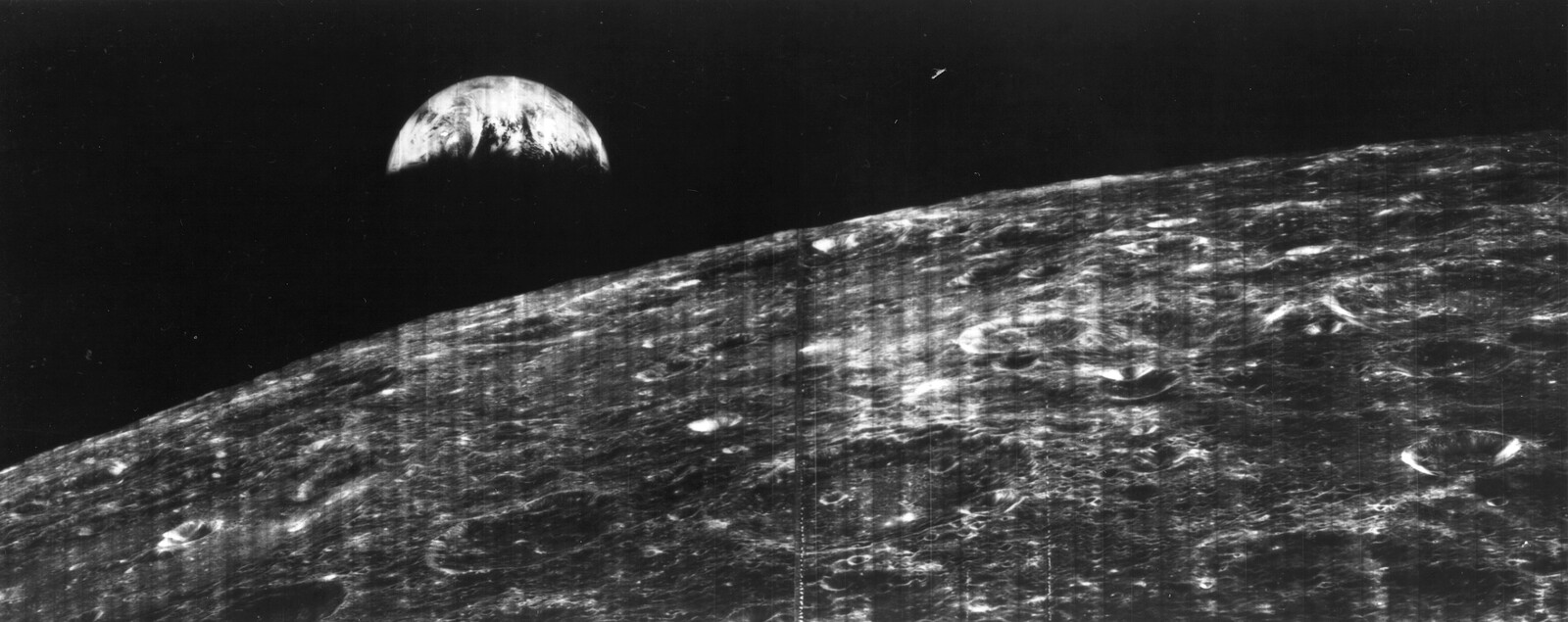

In the twenty-first century, we can easily sense that this process of destruction and recreation is only accelerating rather than slowing down. The longing for Heimat will only be intensified instead of being diminished; the dilemma of homecoming can only become more pathological. In fact, two opposed movements are taking place at the same time: planetarization and homecoming. Capital and techno-science, with their assumed universality, have a tendency toward escalation and self-propagation, while the specificity of territory and customs have a tendency to resist what is foreign.

Today’s humans fail to dream. If the dream of flight led to the invention of the airplane, now we have intensifying nightmares of machines. Ultimately, both techno-optimism (in the form of transhumanism) and cultural pessimism meet in their projection of an apocalyptic end.

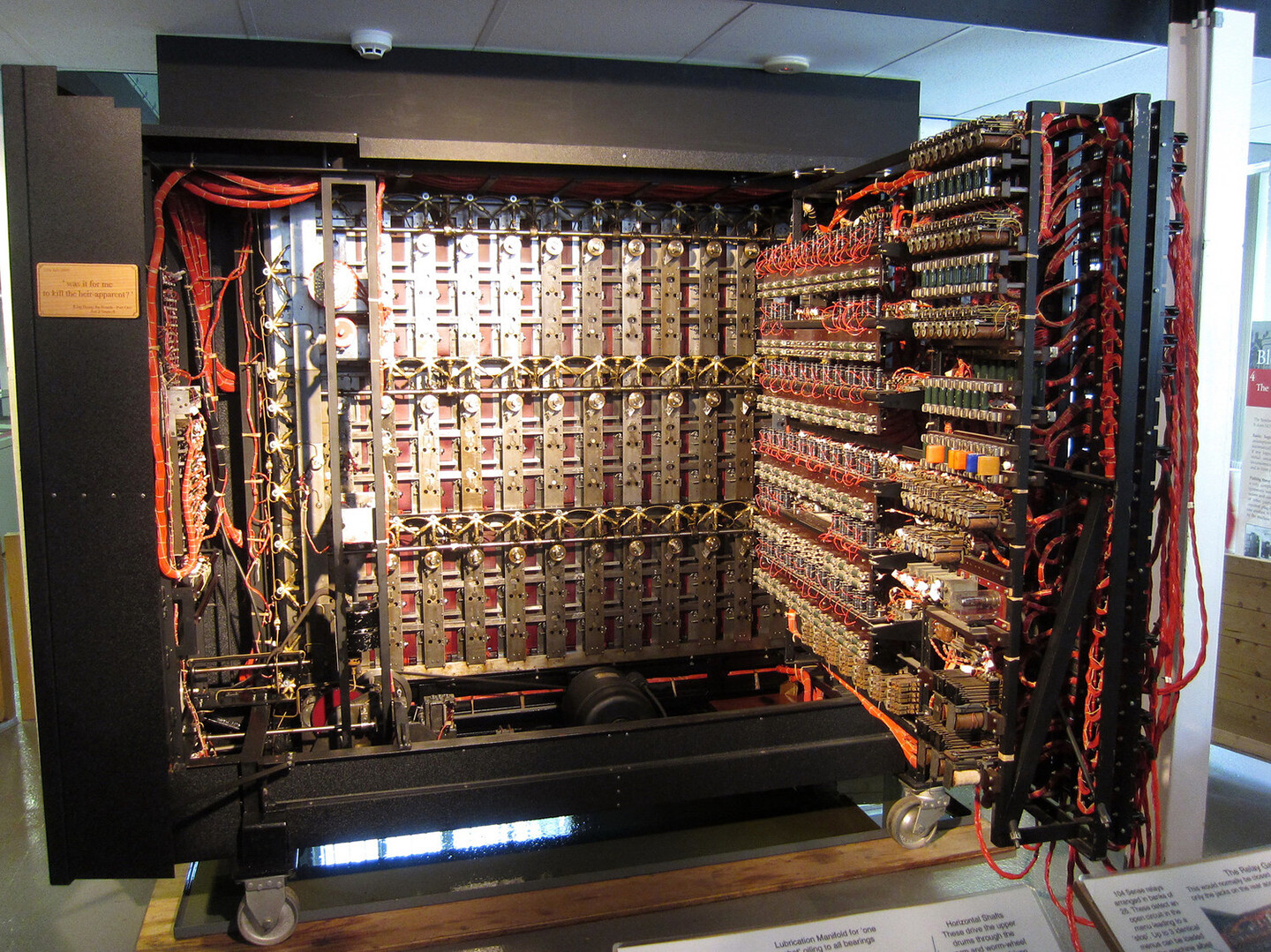

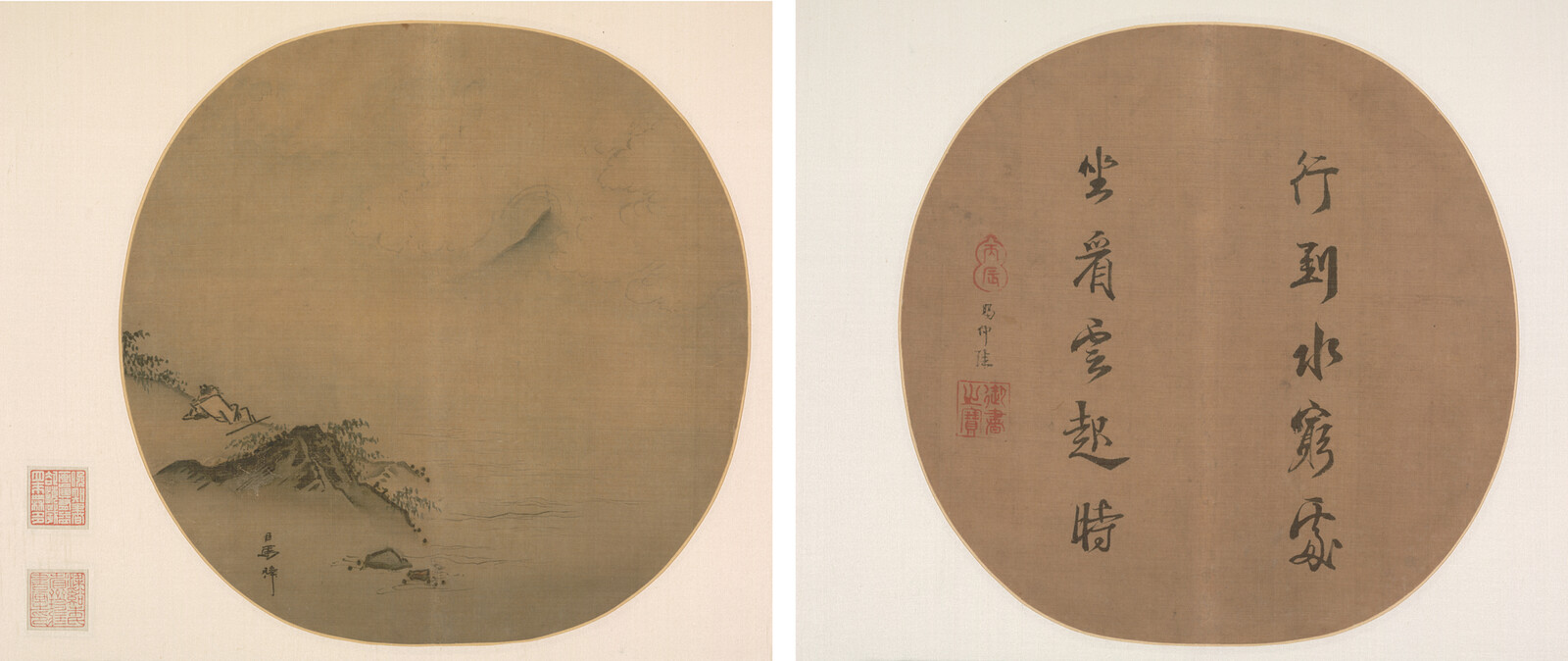

Cybernetic logic is always about the pursuit of a telos. So if you ask artificial intelligence to write a poem, it is always determined by an end, and this end is calculable. But in what I call tragist logic or shanshui logic we find a similar recursive movement, yet the end is something incalculable. So how can we relate back the question of the incalculable to our discussion of the use of artificial intelligence?

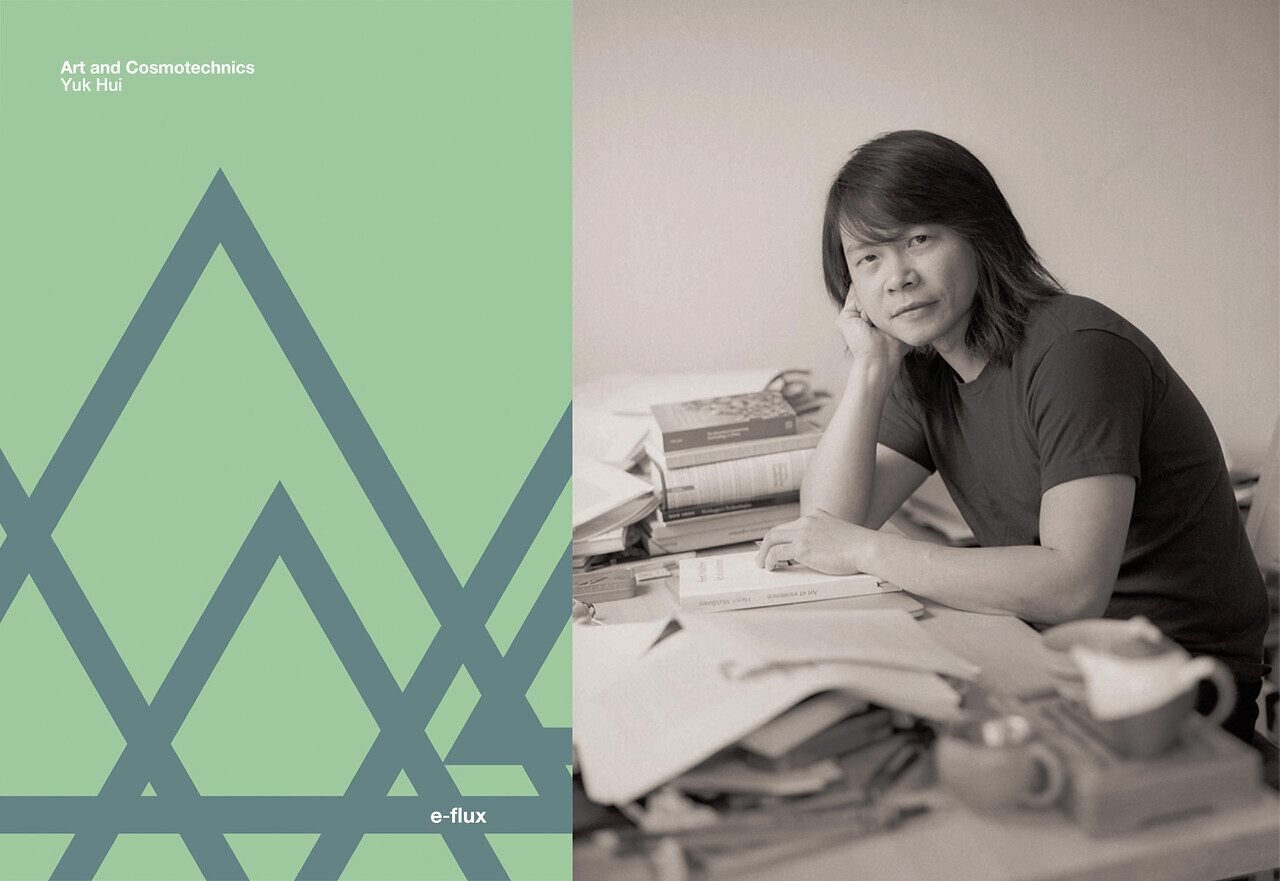

Art and Cosmotechnics: Yuk Hui in conversation with Barry Schwabsky

Maybe there are other ways of overcoming modernity that remain important for us today. War is not the most desirable thing, though it is always a possibility as long as the sovereign state remains the only reality of international politics, since sovereignty presupposes the possibility of war.

If, since Walter Benjamin—or even since the avant-garde before Benjamin—we have been trying to ask how technology changes the concept of art, as you find in Duchamp, can we now turn the question around and ask how art can transform technology? I think this is an important question not only in a conceptual sense, but also in a diplomatic one. If you were to talk to an engineer about an art project, how would you talk to them? Do you simply want to import this or that technology to create some kind of a new experience? Or do you want to influence how technology is made, how technology is conceived, how technology ought to be developed? I think we can also turn the question around further by asking: How can art contribute to the imagination of technological development?

Art and Cosmotechnics

Yuk Hui

Sense-making (Besinnung) cannot be restored through the negation of planetarization. Rather, thinking has to overcome this condition. This is a matter of life and death. We may want to call this kind of thinking, which is already taking form but has yet to be formulated, “planetary thinking.”