Noemi Smolik

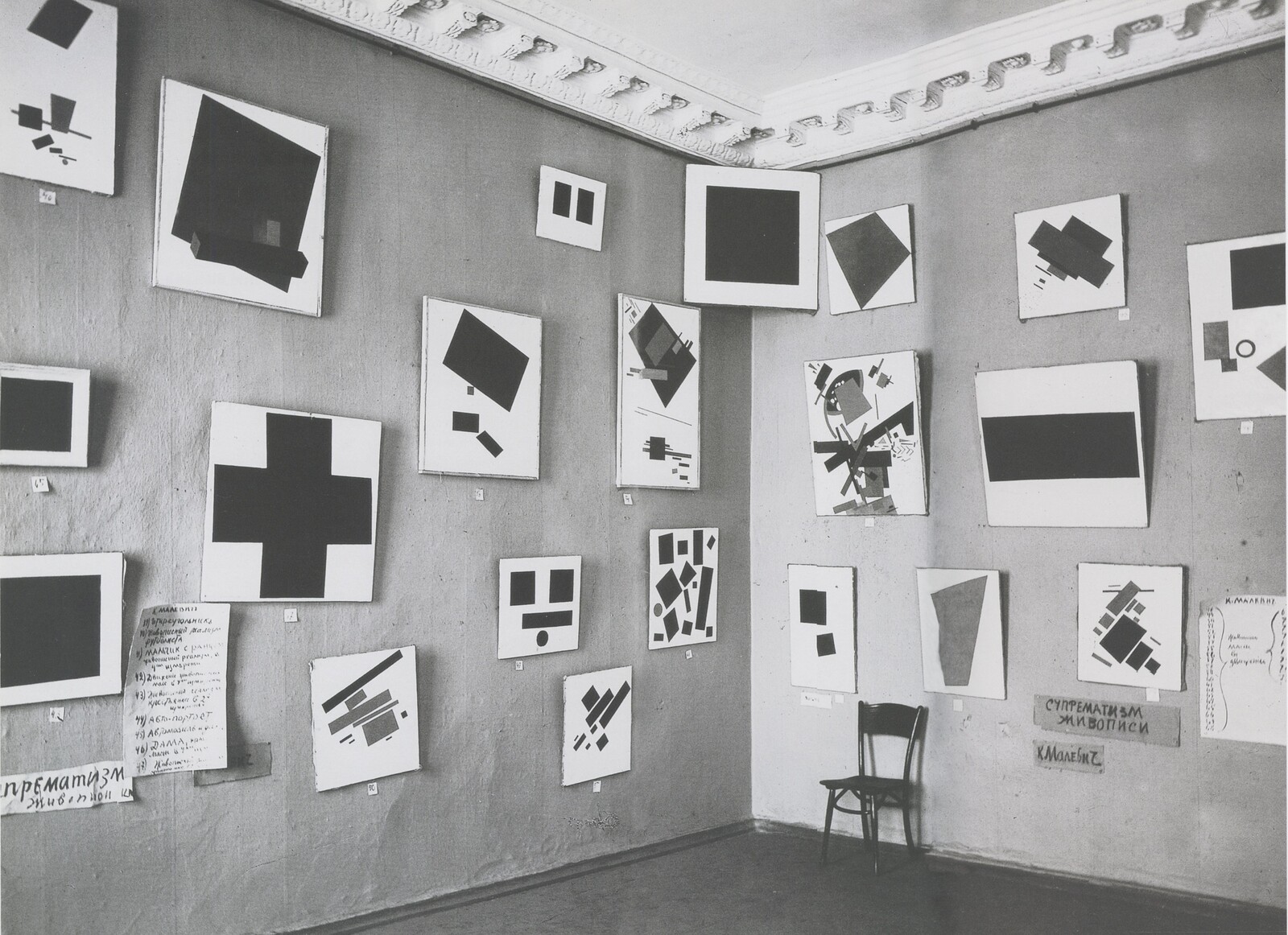

One of the key works of the Russian movement of the early twentieth century is the picture of a black square on a white background by Kazimir Malevich. It was first shown in 1915 during the “Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0,10,” in what was then Petrograd, hung across the corner of one of the exhibition’s rooms. This was how peasants hung the icons in their houses. As well as the black square—listed in the catalogue simply as Square—Malevich also showed his picture of a red square entitled Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions. What is astonishing here, however, is that Malevich relates these nonfigurative pictures, now considered to be among the high points of secular modernism, to the premodern icon and to Russian peasants living in the Orthodox tradition. How is this contradiction to be understood?