Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

April 9, 2021 – Review

Joachim Bandau’s “Die Nichtschönen. Werke 1967–1974”

Aoife Rosenmeyer

At the entrance to Joachim Bandau’s Basel exhibition stands Großes weißes Tor [Large White Gate] (1969/1970), a trio of tall, shiny white columns, each sprouting buffed shoulders and arms that conjoin with its neighbors. Born in Cologne in 1936, Bandau’s childhood was marked by World War Two. He determined to be an artist at 13, after a visit to a Paul Klee exhibition, and went on to study at Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, just ahead of Gerhard Richter and Imi Knoebel. Nonetheless, he grew up in the shadow of the figurative sculpture with which the National Socialists underpinned their credo of racial superiority—like Karl Albiker’s strapping athletes that still welcome visitors to Berlin’s Olympic Park—and began to counter this mechanical perfection in his own work. The anthropomorphic columns of Großes weißes Tor make unconvincing titans: the arms might just be thighs; the bulges don’t swell where they ought to. And the structure is modular, easily assembled and just as easily tidied away. It’s a collaged acropolis for a time of jerky social reconfiguration.

The initial mood of this selective retrospective, a survey of Bandau’s Nichtschönen [Non-beauties] from 1967 to 1974, is black humor. The Nichtschönen are generously proportioned, fiberglass-reinforced polyester forms, sometimes with …

February 24, 2020 – Review

Camille Blatrix’s “Standby Mice Station”

Aoife Rosenmeyer

As is often the case in public institutions, the provision for small children at this show is minimal. An activity table in the middle of the spartan gallery draws attention to the bare floor surrounding it. In Camille Blatrix’s latest test of how spare an exhibition can be, the large, sky-lit space at the Kunsthalle Basel houses four small wooden marquetry pictures and a number of low (and low-key) sculptures. And in the same main gallery there’s a poster—like the activity table, it’s not listed as an artwork—that signposts the nearest Starbucks. Might we find more comfort there? Presenting quasi-artworks that don’t quite fulfil their purposes and signs that direct us back out again, Blatrix interrogates our reasons for coming to the kunsthalle. Are we here for entertainment or aesthetic stimulation, to find something familiar or novel, personal or institutional?

In two small, dimly lit galleries beyond the main space, Hugo Benayoun Bost’s remix of the eight-bar intro to Stand by Me, the 1961 Ben E. King song behind the title of Rob Reiner’s 1986 film, loops, continually heightening and—almost—releasing tension. The artist’s alter ego, another non-artwork, sits crumpled in one corner: a crying face drawn on an old …

June 18, 2019 – Feature

Basel Roundup

Ingo Niermann

Next year, Art Basel turns 50, and animals are still not allowed. There’s not even a “Pets Lounge,” as there is for kids, even though the fair’s premises are big enough to host a whole circus. Art Basel was founded in 1970, a year before Swiss women gained suffrage. Women were allowed in the fair from the very beginning, but animals will probably have to achieve parliamentary representation before the fair will welcome them. While male collectors of visual art have long been fine with consulting their wives and mistresses, they tend to ignore the taste of their pets. Probably not because they give women’s taste on visual art more importance but because it allows them to bond in placid, post-sexual ways. Sounds boring? That’s what non-humans must think about visual art.

Entertainment needs surprise and trust needs solidity. Visual art tries to combine both: to make a joke that works forever. All arts are polluted by this uncanny ambition, but only visual art confronts us as a permanent physical manifestation. In that sense, it shares similar traits with nationalism. Both intend to eternally occupy Earth’s limited space. Nationalism has caused far more casualties and suffering, because artworks can’t fight …

February 21, 2019 – Review

Wong Ping’s “Golden Shower”

Chloe Stead

Without wanting to yuck someone else’s yum (as the saying goes), the breathless list of perversities on view in “Golden Shower”—Wong Ping’s first solo exhibition at a major institution—is enough to make an adult film star blush. There’s the elderly man who gets off on the smell of his pregnant daughter-in-law’s soiled underwear; the husband who darkly fantasizes about turning invisible and sodomizing a police officer; and the teenager who’s obsessed with the, shall we say, unusual placement of his classmate’s breasts on her back. All of this in sharp contrast to the relentlessly cheerful aesthetic of the films themselves, which bring to mind the color-saturated, blocky simplicity of 1980s computer games. It’s this world that the cross-generational protagonists of Ping’s animations must navigate; and they are not handling it well.

Misogynist, violent, and jealousy-fuelled thoughts consume the minds of Ping’s characters, which we hear mostly in first-person accounts, read by the artist himself in deadpan Cantonese. But the activities in each of the seven films featured in the exhibition are communicated free of judgment and—excluding part one and two of “Wong’s Fables” (2018 and 2019 respectively), which are moralistic by design—any discernible lesson. If anything, there is an element of …

February 14, 2018 – Review

Sofia Hultén’s "Here’s the Answer, What’s the Question?"

Aoife Rosenmeyer

I just didn’t get Sofia Hultén’s work Pattern Recognition (2017). Several sets of 12 small perforated metal sheets, like those that hang on workshop walls, are arranged in tidy grids. Each set holds a number of tools or objects, short pieces of chain on one, plastic cutting templates on another, for example. I should have been able to recognize patterns, because the work is inspired by computer scientist Mikhail Bongard’s “Bongard problems,” a series of tests of machine intelligence. But I couldn’t. Eventually—some time later—the obvious dawned on me. I had not to find a pattern within each sheet, or compare each sheet to its neighbor, but identify a pattern occurring in each of a set of six that was not repeated in the opposite six. I had framed the problem incorrectly.

Reframing is an approach that becomes familiar in this survey exhibition, an extended version of which was shown at Ikon Gallery in Birmingham last year. In works dating from 2008 to 2017, Hultén undertakes projects or records actions in which she challenges the logics operating throughout contemporary life and, in particular, surrounding labor and waste. To this end the artist often generates a comprehensible scenario, then undermines the causality …

November 9, 2017 – Review

Charlie Godet Thomas’s “Roman-fleuve”

Aoife Rosenmeyer

An exhibition vitrine in a contemporary exhibition is a knowing nod to long traditions of display. By recreating a form of museum presentation, it relates to what Tony Bennett calls the “museum idea” and its way of defining knowledge and, more broadly, power. Museums, according to Bennett, are places where visitors are taught their place in a society. But Vitrine gallery’s two locations, while behind glass, are antitheses of such authoritative presentation. Founder and director Alys Williams’s model is to create shows displayed in large shop window spaces, visible 24 hours a day. Her London gallery, in Bermondsey Square, is relatively simple; the Basel site, in comparison, has an irregular pentagon footprint with walls placed within, its minute office at the center. Though behind glass, exhibitions are effectively on the outside, not a protected interior. The gallery hunkers under a road bridge, surrounded by a fast food kiosk, a spiral staircase, a supermarket, and a tram stop. Artists have to compete visually and aurally with their surroundings and the everyday life that plays out in a space far from most hermetic art contexts.

Vitrine Basel thus demands mettle from artists; it is never self-evident that their work should be there, entangled …

June 17, 2016 – Review

Art Basel and Liste

Jennifer Piejko

When word got out that Hervé Falciani, a dapper systems engineer at HSBC’s hushed private bank in Geneva, had lifted the identities and details of 130,000 account holders in 2008, the Swiss government was put in the unfortunate position of having to ask its neighbors to extradite this thief or Robin Hood, depending on one’s perspective. These were the same countries whose own citizens had evaded paying taxes on the cash (often wrapped into bricks, sometimes in faraway, foreign currencies) by storing it with HSBC’s Swiss branches. France sheltered the whistleblower and his “Lagarde list,” even sharing the embezzled data with other state governments to help them further their own pursuits of missing tax income, often from its wealthiest citizens.

The centuries-old Swiss banking tradition of total discretion, even at its highest stakes, was finally broken. Falciani was not only a highly skilled technician, he was also an astute witness of both formal and informal office protocol. This was vital, since there was often no official documentation to refer to, or dispute: the majority of the private bank’s clients opted out of receiving monthly bank statements, a process detailed in a recent New Yorker profile that reads like a Hollywood script. …

January 14, 2016 – Review

John Wood and Paul Harrison, “Some things are undesigned"

Ingo Niermann

There are countless jokes about modern art being ridiculously boring and about people only being into it to distinguish themselves from the unrefined, who expect from art what hungry people expect from food.

When people keep making fun of you, you can pretend not to listen, or you can start making fun of yourself. But in both cases, your stance is a reactive one. To undermine the twitting, you better create some ambiguity: are you really being serious with that boring stuff, or are you just making fun of yourself?

Since the breakthrough of Marcel Duchamp, most art that is canonically understood as good is fueled by such an ambiguity. The dubious balance between serious and silly itself became a predictable formula. Which made it tempting for some artists to stand out by insisting on being boringly meaningful or boringly silly. In those cases, it’s less a reaction to outsiders making fun of them than to the well-balanced ambiguity of the other artists.

The works of the British artists John Wood and Paul Harrison play on the boringly silly side. Their current show at von Bartha, “Some things are undesigned,” is no exception: a painting with the words “LEFT AND RIGHT” in one …

June 18, 2015 – Review

Art Basel

Ingo Niermann

During Art Basel’s preview days most visitors appear to be elderly heterosexual couples. More so than having children, collecting art bears the promise of keeping wealthy couples together. Children grow up and leave the house, but the collection stays and can grow forever. Like people, collections cannot be divided without killing them—still, that’s what a divorce asks you to do.

From a cynical perspective, husbands only collect art to give their wives the illusion that they still share some substantial interests with them, and wives only collect art to give their husbands the illusion that they have lost all libido beyond the little sex and eroticism they still experience together.

While the female half of this collector couple rather tries to resemble an artwork—colorful and ageless—the male part rather imitates the appearance of money with monochrome (preferably dark blue) suits. Of course there are exceptions to the rule, in particular when both spouses try to resemble artworks, or when both spouses try to resemble money.

Collecting art is the best that bourgeois society has to offer to reassure that sex isn’t everything a man and woman could share. Food makes you fat, drugs make you stupid, sports make you attractive again and subsequently …

June 17, 2015 – Review

Art Basel

Stefan Kobel

There is a first time for everything! Speaking at Art Basel’s media reception, director Marc Spiegler remarked that “the line between finance and art sometimes seems hard to discern.” Pressed, he admitted that he had never drawn this connection in public before, specifying that “art can be used as a financial asset but a very risky one: there is a high carrying cost involved with owning art due to issues such as storage, insurance, and conservation. It can turn illiquid overnight. Meaning, there are artists whose work has suddenly become impossible to sell at the original price. While there are many people who have invested in art successfully, they are either very knowledgeable themselves or they have very good advisors.” Jürg Zeltner, the President of UBS Wealth Management, had no doubt that art had become an asset.

In the past, everybody at the fair avoided giving even the slightest impression that art might resemble a commodity. Art Basel was all about putting together the best art, by the best artists, represented by the best galleries, and placing it in the best private and public collections. It got a bit monotonous over the years.

Suddenly Art Basel acknowledges the obvious: art is widely …

September 26, 2014 – Review

Stephen Willats’s “Attracting the Attractor”

Aoife Rosenmeyer

It’s tempting to throw Londoner Stephen Willats in with the crop of neglected artists born in the first half of the last century currently being “unearthed” by the voracious contemporary market machine. Willats, born in 1943, may fit the generation, but to suggest that he required rediscovery would be misleading. Nonetheless, despite solo shows in the UK alone in the last two years at the South London Gallery, Raven Row, Modern Art Oxford, and Victoria Miro—a gallery with whom he has a longstanding collaboration—his work still feels anachronistic. The earliest piece in this exhibition of drawings at Anne Mosseri-Marlio Galerie is from 2008, yet Willats’ practice retains the positivism of the mid-1960s, when he first started working.

“Attracting the Attractor” is a cabinet-style presentation of 17 drawings and 2 digitized Super-8 films. The visitor first encounters Making a Rich Connection (2008), a drawing topped with a frieze of figures photographed in the street; lines pointing to some of these people identify them in various relationships from “stranger,” to “accomplice,” or “soulmate.” Below the frieze these identities are associated with squares that interact in different manners, as defined by the lines between and around them. These interactions and connections become progressively denser …

June 19, 2014 – Review

Art Basel

Laura McLean-Ferris

“Real experiments that really fail have to take place in a festival, rather than in an exhibition, because this way you don’t have to take responsibility for them two or three weeks later when they are still going on,” said Klaus Biesenbach at the opening of “14 Rooms,” an exhibition of “living sculptures” that he developed with Hans Ulrich Obrist in 2011 (as “11 Rooms”), which has since arrived at this year’s Art Basel, taking shelter under its branded umbrella. Art fairs truly are the modern festival, a theatre of things and money—but the majority of the things on stage at art fairs do aspire to a state of permanence.

“14 Rooms” takes place in Basel’s oldest trade fair hall, one transformed by Swiss architectural heroes Herzog & de Meuron into a wide corridor space with 14 small, white cubes leading off it, each behind closed doors with wooden handles. Beyond them one finds groups of people performing instructional works, like Allora & Calzadilla’s Revolving Door (2011), in which a line of dancers rotates around a central axis, blocking the visitor’s path, and stamping with various shades of aggression, or Roman Ondák’s Swap (2011)—a person at a table barters with the …

June 17, 2012 – Feature

Art Basel roundup

Laura McLean-Ferris

Jeff Koons’s giant blue egg sculpture—that outlandishly chatoyant and seductive object—looks as though it could have landed from another planet or another time. Its cracked top serves as a reminder of the way that Koons created a fundamental fracture within art history with his compelling work, and I was reminded of the artist’s monumental impact as I visited his exhibition at the Fondation Beyeler coinciding with the Art Basel fair, partly because it informed nearly everything I saw subsequently. The very first work in the show is the utterly eerie The New Jeff Koons (1980), a lightbox displaying an image of the artist as a young boy posing with crayons and a coloring book like the perfect child, his expression every bit the airy adult Jeff we have come to know: clear-eyed, polite and unnervingly serene, with his “how may I help you” smile. This image serves as an introduction to the artist’s brilliant Hoover sculptures and shampoo polishers in Plexiglas cubes, which revel in the purity of their box-fresh newness and aspirational product names—Celebrity and so forth, and assisted by Koons’s presentation and uncanny doublings. These, now more than thirty years old, are nothing short of visionary. They seem …

June 14, 2012 – Review

Art | 43 | Basel

Colin Chinnery

Upon entering Art Basel straight off the train from Kassel, I cannot but help recall the last time Documenta coincided with Art Basel. Back in 2007 the art market, animated by the roaring finance sector, had almost superhero-like qualities, with special powers like selling work before it even existed, and adding zeros to the end of prices. Projects in Art Unlimited then were positively bombastic, like the Christoph Büchel piece Unplugged (Simply Botiful) 2006/07 that could have filled a medium-sized museum. This sensory assault was contrasted by the curatorially austere Documenta XII and Skulptur Projekte Münster that opened after Basel in quick succession. Five years on, the art world is quite a different place. Art cannot escape its relative context, and the context of the market is possibly the most relative of all. The financial anguish of the 2008 crash and the palpable threat of a new recession across Europe has forced the market to think deep and hard about the meaning of longevity. Judging from this year’s Art Basel, longevity means… thinking deep and hard; about what artists have to say, about what works speak most eloquently, and about putting on rigorous shows.

I have to confess this was not …

March 13, 2012 – Review

Marjetica Potrč’s "Acre: Rural School"

Quinn Latimer

A few months ago there was a photograph circulating on Facebook that made my stomach turn. Not knowing where to find it now, I simply (if wincingly) typed into Google the following: “photograph of Indian chief crying.” The image immediately appeared, conjured magically out of the internet ether. There he was, an older, bare-chested, dark-skinned man in chinos and a fluorescent-yellow, halo-like headdress, sitting in a chair, his head bowed into his hand, sobbing. Other men, sans ceremonial headdress, sit in chairs behind him, dismayed or stunned or blank. A man in a button-down shirt stands in front of the chief, either attempting to console or perhaps he’s the deliverer of the devastating news. Terribly, banally, the awkwardly worded caption below provided the entirely expected answer:

Chief Raoni cries when he learns that Brazilian president Dilma released the beginning of construction of the hydroelectric plant of Belo Monte, even after tens of thousands of letters and emails addressed to her and which were ignored as the more than 600,000 signatures. That is, the death sentence of the peoples of Great Bend of the Xingu River is enacted. Belo Monte will inundate at least 400,000 hectares of forest, an area bigger than …

June 19, 2011 – Feature

Art Basel roundup

Vivian Sky Rehberg

One hears a lot of grumbling about Art Basel. Or maybe it’s just the leftist company I keep. Still, I was surprised to meet more than a few people who had travelled all the way to Basel for reasons peripherally related to the fair but who had refused to step foot in it, according to the misguided “principle” that blinding oneself to the commerce of art is proof of genuine anti-capitalist credentials. Whatever happened to “know thine enemy”? And is the fair really the enemy? Well, historical materialists like me don’t believe in fairy tales and—guess what?—ignoring the art market does not make it go away. My choreographed wander through the behemoth Hall 2 was exhausting, terribly instructive and, in some cases, more aesthetically gratifying than many of the exhibitions I’ve recently seen in non-profit institutions.

Worth the trip alone: Isabella Bortolozzi’s stand, especially Carol Rama’s Movimento e Immobilita’ di Birnam (1977) with its limp bouquet of flaccid black rubber bicycle tire tubes, visually spare yet enticing. In an entirely different register, at Air de Paris, I didn’t know how to quit Dorothy Iannone’s Brokeback Mountain (2010), a brightly painted freestanding object, like a miniature altar, featuring portraits of the characters …

June 17, 2011 – Review

Art Basel

Quinn Latimer

How does one write about an art fair? Dear reader, I am being sincere. If one is not an art market journalist gleefully scribbling down the cost of a collector or celebrity’s (or celebrity collector’s) pre-preview purchase of huge German neon painting, my question is less rhetorical than the subtext of missives sent off to editors after their anxious writers have made the rounds. For a fair like Art Basel—the high, giddy priestess of art fairs—to say the work hung in the white booths is good is redundant. Of course it’s good. It’s insane. So. Where do we go now? Let’s talk about some works, yes, and I’ll even break it down by section.

Art Statements

It’s the curated section devoted to solo presentations of young, promising artists. Perusing it can help identify specific trends—or not. It is a small selection, after all. Still, I noted a turn away from the spare, chic formalism of past years: there were less white plinths and folded c-prints strewn across booth floors, more vivid color and essayistic video and weird, joyful pomp. If there was one booth that caught my eye and seemed an apt metaphor for the fair’s crush of art, it was Petrit …

September 8, 2010 – Review

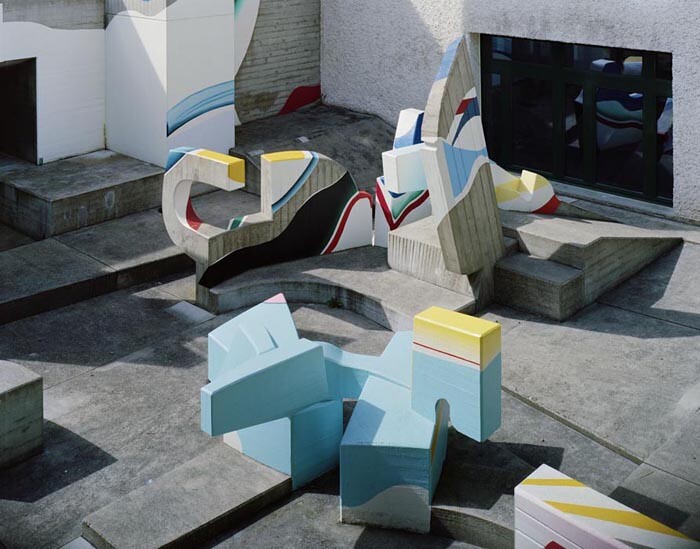

Michael Grossert’s "3 Playgrounds, 1967–1975" at New Jerseyy, Switzerland

Quinn Latimer

It can be difficult in our age of post-everything to comprehend the political import and impact of art and architecture in the 20th century, when stakes—see: two world wars, and the modernist and/or progressive ardor that arose around them—were high. It is far easier in our climate, in which art and politics often feel like estranged commuters, to understand such work as part of a formalist or art-historical continuum. An exception might be the experimental, postwar playgrounds of America and Europe—as designed by artists, pedagogues, and innovators like Isamu Noguchi, Aldo van Eyck, and Carl Theodor Sørensen—which even now retain a tangible weirdness and palpable utopian spirit. That playgrounds are a social project is a given, even when designed by artists with “purely” aesthetic intentions.

If Noguchi’s unrealized “Play Mountain” (1933) united modernist sculptural principles and Japanese design—Noguchi felt it was the “progenitor of playgrounds as sculptural landscapes”—and Aldo Van Eyck employed the formalism of the De Stijl artists in the 700 postwar playgrounds he designed in Amsterdam, the Basel sculptor Michael Grossert’s contribution to the field appears small indeed. It constitutes just three projects—one unrealized—made between 1967 and 1975. Nevertheless, these playgrounds, as seen in video, photographs, models, and prototypes, …

June 28, 2010 – Review

Art Parcours at Art Basel 41

Colin Chinnery

After seeing what felt like thousands of artworks in hundreds of booths at the fairs, the feeling of walking around Basel’s old town in search of the nine individual art projects of Jens Hoffmann’s Art Parcours was a welcome hiatus from fair fatigue. But what made Parcours a coherent project was the difference in mentalities and attitudes between the various works, and the rhythm of mood that was created from one work to the next. Especially important was the live factor, feeling the presence of the artist. Instead of attempting to create a common denominator between the works, Hoffmann worked with artists who gave different interpretations of the processes of observation, participation, narrative, and the theatrical.

Ryan Gander’s Loose Associations, was the perfect starting point. Gander’s work took the form of an open lecture that weaved different personal anecdotes and observations the artist made over the years. Loose Associations has become a well-known work since it was first performed in 2002, but few people have had the chance to experience this event. The relaxed delivery by the artist, the idiosyncratic sense of curiosity that made Gander collect his anecdotes, and the way the various subjects blend into each other makes this …

June 25, 2010 – Review

Art Basel 41

April Lamm

The Finest Worksong 16 June 2010

Last weekend during the Berlin Biennale I found myself wedged up against a rock star. (Rock star? That’s a far cry from what Michael Stipe means. His lyrics gave solace to a whole generation of purblind pubescents in the late 80s.) He said hello, shyly, and I asked him, bluntly, about an album cover clutched under his arm. We began to talk (why couldn’t I drum up a lyric like “Buy the sky and tell the sky”?) and the last words I could murmur, before being interrupted by the penetrating cell phone were, “Trust your own eyes.”

“Trust my own eyes” was the advice I would follow for myself while harrying through the halls of Art Basel. I decided to begin at random by seeking out a gallery where I know/love their artists but they don’t know me: Air de Paris (read: half-objective territory, impossible to be corrupted by the charm of words or personal relationships). First thing I saw was Bibliothèque du Paradise (2009) by Philippe Parreno, a work I had seen, or at least a similar one, in Paris, at the FIAC last October. It’s an armful of paperbacks covered in Pantone pastel colors. …

Load more