Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

July 29, 2022 – Review

Manifesta 14, “It matters what worlds world worlds: how to tell stories otherwise”

Cathryn Drake

For its 14th edition, the nomadic European biennial Manifesta has taken up temporary residence in various cultural institutions and derelict spaces in and around Pristina, the capital of Kosovo, where creative mediator Catherine Nichols invited artists and practitioners to explore modes of storytelling across cultures. As a contested nation state, Kosovo embodies many of the most pressing and complex issues facing society today. When is a country a country? How many people have to say it is for it to be? Who has the authority to declare a territory as a nation? Does the population need to be homogenous? Who is nationalism good for? How can we all live together and be free? Roaming the city in search of the exhibitions and “artistic interventions”—by 102 artists in 25 locations, from an Ottoman-era hammam to a former brick factory—I attempted to plot pieces of the puzzle into a coherent picture. Interacting with locals in Pristina was inevitable, both to find the far-flung (and often vaguely signposted) locations and to glean how the tumultuous, not-so-distant past led to the complex present.

The main exhibition, titled “The Grand Scheme of Things,” is hosted on seven floors of the Grand Hotel Pristina, a decadent …

September 25, 2018 – Review

Revisiting Manifesta 12

Arseny Zhilyaev

Arseny Zhilyaev traveled to Manifesta, the European Nomadic Biennial. Back in the day, it was one of the Old World’s most experimental art venues. “The Planetary Garden,” its twelfth edition, opened in June in Palermo.

The attempt by Italy’s newly minted right-wing populist government to reject a boatload of 629 refugees from Africa this June triggered a story that became Manifesta 12’s epigraph. A few days before the biennial’s official press conference, Palermo’s mayor, Leoluca Orlando, stormily announced he was ready to take on the federal government in Rome. He argued Italian authorities were violating international conventions and humanitarian principles, thus leaving him with no choice but to let the ship carrying the refugees dock at the port of Palermo, a city that has long incarnated hospitality and cultural intercourse. Orlando spoke on nearly the same topic at the opening press conference. Needless to say, given the previous two biennials—Manifesta 10’s “window on Europe,” held amid St. Petersburg’s imperial splendor, and Manifesta 11’s discussions of how artists could make money, held in one of the world’s most expensive cities, Zurich—the rhetorical tone adopted by Manifesta 12 seems timelier and more in keeping with the biennial’s original brief to exhibit new, …

June 21, 2018 – Review

Guy Mees’s “Espace Perdu (Verloren Ruimte)”—an exhibition in two chapters

Helena Tatay

Guy Mees (1935–2003) was a leading figure of the Belgian avant-garde whose enigmatic work combined formal diversity with conceptual rigor. A consecutive pair of exhibitions at Barcelona’s ProjecteSD—the first from March to April, the second from May to June—shed light on his career, offering carefully curated series of works alongside archival materials that situate his practice in a wider art-historical background. Mees’s interest in serial structures, repetition, formal reduction, and industrial materials was in some ways typical of minimalism. But as these two exhibitions attest, his highly personal artistic language balanced formal rigor with fragile materials—stretched lace, pale neon, narrow strips of paper—to lend his work its characteristic delicacy.

Each exhibition loosely corresponds to a distinct period in Mees’s career, during which he produced a series of works under the collective title “Verloren Ruimte” [Lost Space]. The first group, made between 1960 and 1967, feature simple, geometric wood and aluminum sculptures overlaid with industrial lace. The second, which Mees began in the mid-1980s and completed in the mid-1990s, is looser and more vivid, comprising strips of colored paper pinned to the wall. Despite their formal differences, both series investigate the relationship between art objects and their exhibitionary environments. Displaying these works …

June 20, 2018 – Review

Manifesta 12

Barbara Casavecchia

In 2001, Maurizio Cattelan invited a group of the 49th Venice Biennale’s VIP guests to join a satellite event in Palermo: a cocktail reception in Bellolampo, the city’s main landfill, where the artist had installed a larger-than-life replica of the Hollywood Sign overlooking the Conca d’Oro, the defaced coastal “golden bowl” once filled with citrus groves. It was a vitriolic triumph of trash and a homage to the fictionalization of “a city that has to struggle every day with its own conceptions of its past and present,” the artist said. A few months later, Diego Cammarata, the candidate from Silvio Berlusconi’s party Forza Italia, won the local elections. His victory ended the long tenure of Leoluca Orlando, who during two nonconsecutive terms as mayor between 1985 and 2000 championed the anti-mafia movement known as the Palermo Spring.

Seventeen years later, Orlando is back in the mayor’s seat for the fifth time, as leader of a center-left coalition; a new biennale has landed in town; and another work—art collective Rotor’s installation Da quassù è tutta un’altra cosa [From up here, everything looks different] (2018)—invites viewers to visit another devastated hill perched atop the city. Nicknamed “the hill of shame,” the Pizzo Sella …

March 19, 2018 – Review

Allora & Calzadilla

Mariana Cánepa Luna

A piercing whistle punctuates the blaring of a trumpet. But in the columned central space of the Fundació Antoni Tàpies, the only visible instrument is a grand piano. For three days a week throughout the course of the exhibition, the instrument is played—and, one could say, worn—by a pianist who stands in a hole cut into its center. Leaning over the rim of the piano to strike the keys, the performer energetically interprets the fourth movement of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 (1824), while slowly pushing the wheeled instrument around the space. The building has become a musical box, the exhibition orchestrated so that one movement flows into the other, spilling through the gallery’s spaces to create a dissonant soundscape.

The piano of Stop, Repair, Prepare: Variations on Ode to Joy for a Prepared Piano (2008) could be thought of as the lead performer of Puerto Rico-based duo Allora & Calzadilla’s show. Popularly known as “Ode to Joy,” Beethoven’s piece has often been interpreted as a defense or celebration of humanist values, and in 1985 the European Union adopted it as its official anthem. Yet, as Slavoj Žižek has noted, the tune’s “universal adaptability” has made it vulnerable to use …

January 9, 2018 – Review

Holly White’s “Orange World”

Lizzie Homersham

“If you believe you’re a citizen of the world, you’re a citizen of nowhere. You don’t understand what the very word ‘citizenship’ means.” I was sent into a cold rage when I read these words what feels like a never-ending day ago in the transcript from Theresa May’s Conservative Party Conference speech of October 2016. The sentences still reverberate. Supposedly they targeted “people in positions of power [who] behave as though they have more in common with international elites than with the people down the road, the people they employ, the people they pass in the street.” They simultaneously scorned free movement, no-borders politics, and international solidarity. For those opposed to the Leave campaign’s catalyzing effects on xenophobia, disinvestment, and abstract nationalist desire to “take back control,” a heavy blow to hope had already been struck by the vote back in June. Following her appointment as prime minister, May’s formal response to the referendum result set the electorate’s action into cruel and condescending relief.

“Orange World” opened in Barcelona two months after the Catalan referendum for independence from Spain. During my stay there, the city is punctuated by pro-independence yellow ribbons tied to railings or graffitied onto walls. Apartment buildings are …

September 15, 2017 – Review

“The Space of Dreams”

Ingo Niermann

Earlier this summer, after a public talk between Elena Sorokina and my wife, Chus Martínez, the three of us were invited by Eduard Mayoral of Galeria Mayoral to dinner. We hadn’t yet reached dessert when Eduard asked us what to make of Salvador Dalí. They were about to open a group exhibition, “The Space of Dreams,” curated by poet Vicenç Altaió, that would include Dalí’s work. Last year the gallery had also exhibited a series of six of Dalí’s fashion sketches from 1965, with elegantly absurd designs for beachwear and evening robes. These drawings were still for sale for 100,000 euro each.

Apart from his major paintings, the market for Dalí remains murky. Not only did he flood the market by signing all and everything, his historical importance is also in question. When I interviewed Boris Groys in 2010, he used Dalí as a perfect example of an artist who didn’t manage to appeal to both “the mass public and the informed part of the audience.” “Dalí overdid it, lapsed too far into poor taste and did not stand in any central tradition.”

The typical counter-example of someone catering to the art elite and the masses equally (who Groys also mentioned) is …

November 8, 2016 – Review

Ana Jotta’s “Abans que me n’oblidi (Before I forget)”

Mariana Cánepa Luna

While it has been widely exhibited in her native Portugal, Ana Jotta’s work hasn’t been presented in depth to the Barcelona public since the early 1990s. So this mini-survey of her production from 1980 to the present, framed as part of the Barcelona Gallery Weekend, is overdue. “Abans que me n’oblidi (Before I forget)” begins (or ends) at the intermediary patio space that one crosses before entering the main exhibition space at ProjecteSD. Part of a curved wall is covered with irregular patches of light gray and pale pink paint, as if emulating swatch tests for a redecoration. This playful gesture sets the tone for the exhibition inside, a somber and subtle palette of delicate intonations and provisional arrangements.

A dozen pieces are sparingly hung around the perimeter of the exhibition space. A large aquatint depicts a delicate wire fence (Untitled, 2002) and a portable projection screen is covered with a torrent of black-and-white strokes (Un Printemps 2008, 2008). This is the only work in the exhibition that appears to confirm Jotta’s own reductive description of herself as a painter, despite having tackled all manner of craft, from embroidery to writing. The sleek finish of the blue steel wall piece Cloud …

June 28, 2016 – Review

Loop Barcelona

Lucy Reynolds

Barcelona’s Loop art fair, which started in 2003, is the oldest and most established initiative to assert the commercial potential of film and video. The medium’s ephemeral nature, and its associations with the very different market values of cinema, have contributed to a continued reluctance from collectors, attracted by the aura of more traditional art forms. Paradoxically, these tricky market credentials have recently endowed the moving image with a critical cachet in institutional art spaces and museums. As the institutional assimilation of practices traditionally seen as marginal, and oppositional, to the art market continues—from experimental film to the documentary—the instrumental role of film and video takes on a significant historical resonance in art discourse. In order to assign value to this wayward and ambiguous media within the context of an art fair, Loop has to negotiate a conflicted territory. How to maintain its more market-driven function without appearing to dismiss these historic discourses of disavowal, which will themselves provide validation for the sale of moving image works?

I received the answer at my hotel desk, where I received the exhibition catalogue for “Empathy,” Harun Farocki’s show at the Fundació Antoni Tàpies. The enclosed compliment slip asserts Farocki’s role as a “close …

June 13, 2016 – Review

“What People Do For Money,” Manifesta 11

Ingo Niermann

Contemporary artists are great at being dilettantes. Some make a point of how liberating it is to lack skill, others of how liberating it is to delegate to those who know better. Meanwhile, machines continue to outdo humans in more and more skills. More and more humans work in some sort of managerial position, in which their job profile resembles that of a contemporary artist: a bit of research, a bit of creativity, a bit of giving orders, a bit of receiving orders, and lots of micro-communication. More and more jobs are short-term and poorly paid—like most commissions for artists. Those professionals who don’t work like artists act like artists in their spare time, whether by creating artifacts or by remodeling their personas.

Today, being an artist is the norm; specialists are the exotic birds that artists once were. To work with a specialist has become an exquisite experience that can easily be turned into a piece of art. This must have been the starting point for German artist Christian Jankowski when curating the 11th edition of the “European biennial” Manifesta, hosted this time by Zurich. Jankowski—who made himself known for works created with the help of fortune tellers, speechwriters, or …

January 30, 2015 – Review

Jochen Lempert

Carles Guerra

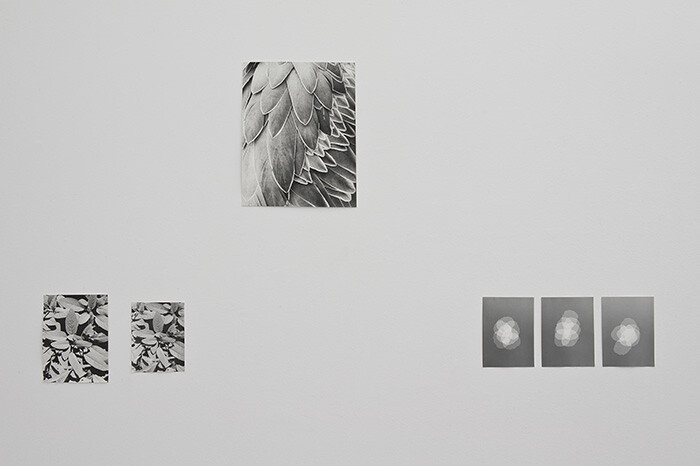

Jochen Lempert’s work is often presented in large compositions of black-and-white photographs demanding close inspection. This time is no different. Ranging from medium-sized to small and tiny prints, this exhibition of his now classic repertoire of flora and fauna gives visitors the feeling of being at an amateur’s show, where the standards of high-end presentation have been disregarded. Since the early 1990s Lempert has been known as the photographer who was once a biologist, and with this knowledge the scale of the gallery space seems ideal; a room not big enough to belittle such subtle work, which could easily be confused with scientific materials of a lesser order. Although most of the photographs in the show are organized in diptychs, triptychs, and series including several pictures, the visitor is easily drawn into the detail. A few steps away from the wall it all looks like a harmonious world: natural objects from different orders merge into seamless forms.

But upon closer examination paradoxical connections manage to unsettle what at first glance seemed unproblematic. A shelf with eight photographs and one photogram (Botanical Box [2014]) emblematizes this type of composition. Among the diverse typologies of leaves depicted there sits a blurry reproduction of …

November 21, 2014 – Review

Harun Farocki’s “4 films from 1967–1997. An homage curated by Antje Ehmann”

Carles Guerra

This exhibition is one of the first since Harun Farocki’s unexpected death in July. In the absence of the artist himself, “4 films from 1967 to 1997” pays tribute to the man—chosen by his partner and collaborator, Antje Ehmann—who has been perhaps among the most influential artists and filmmakers of the second half of the twentieth century. However, this is a reputation gained by a modest and straightforward output, as is reflected by this presentation at àngels barcelona. Three of the works emerge from a single-channel video monitor and another is projected onto the wall. The unassuming atmosphere is the perfect setting for this 76-minute program bringing together examples from Farocki’s varying and strategic forms of narrative, from militancy to critique. The Words of the Chairman (1967) and Their Newspapers (1968) recall the agitprop and politically informed practices in art and film of the late 1960s; whereas Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet at Work on a film based on Franz Kafka’s “Amerika” (1983) and The Expression of Hands (1997) are representative of his strong and analytical approach to film culture.

This is the same gallery where early installations of Serious Games (2009–2010) and Parallel I-IV (2012–2014) were presented at different stages …

July 17, 2014 – Review

Andrea Büttner’s "Tische"

Max Andrews / Mariana Cánepa Luna

Pursuing a clearly spiritual approach within a Christian cultural and ethical context, Andrea Büttner is one of the few contemporary artists who could plausibly cite St. Francis of Assisi, the twelfth-century Catholic friar who committed himself to a life of poverty, as a key influence. Her work Tische [Tables] (2013), which addresses notions of the “blessed poor” (those who disavow material possessions as a way of being closer to God) and the prehistory of farm-to-table dining, is a carefully constructed homily on what art can bring to the table on poverty, without ever lapsing into austerity chic. Büttner’s meager solo presentation at Barcelona’s NoguerasBlanchard forms part of a year-long exhibition series entitled “The Story Behind,” organized by in-house curator Direlia Lazo. In it, the artist exhibits four out of the original thirteen tabletop compositions she created for a dinner held at the Museum für Moderne Kunst Zollamt in Frankfurt last year. At Büttner’s invitation, five talks were given at dinner and recorded. Entitled Tischreden [Dinner speeches] (2013), the resulting extended audio recordings of the speeches and the ebb and flow of dinner conversation now serve as prime stimulants for the discursive appetites of the Barcelona gallery’s visitors.

Büttner’s four dining tables—and …

June 2, 2012 – Review

"The Deep of the Modern," Manifesta 9

Jonas Žakaitis

OK, let’s start with a joke heard by the author on the way to the site of Manifesta 9. Two men were waiting for a bus together in the central station of Genk (Belgium), one of them equipped with a basket full of red apples.

“Here, have an apple,” the man said. “They said in the shop these were Bio apples, whatever that means. I think they come from a real pig.”

Belgian humor is seriously twisted. And there’s plenty of room for it at the defunct Waterschei coal mine where the biennial is taking place. This does not mean to say that Manifesta 9 is one twisted joke… but we’ll get back to that later.

So the show is titled “The Deep of the Modern” (to be read in a slow rumbling voice) and is curated by Cuauhtémoc Medina together with Dawn Ades and Katerina Gregos. It is all about coal. Or, to be more precise, coal is the semantic and morphological engine behind more or less everything in the exhibition. Of all the conceivable approaches to the material, quite predictably, political economy gets the ball most of the time. Genk is a town built for the sole purpose of getting the …

Load more