The title “Foreigners Everywhere,” derived from the neon text works by Claire Fontaine that hang over the entrances to both sites of the international exhibition at the Venice Biennale, holds out the promise of a productive confusion. In the Italian expression visible on the reverse of the English, stranieri ovunque, the phrase carries a more overt implication of strangeness with the same edge of hostility, so that the visitor might brace themselves for a series of encounters that are—like the experience of foreignness itself—bewildering, unsettling, and fundamentally unsafe.1

But there is no need to do so. Because while the adoption of a bilingual sign as motto for the Biennale’s centerpiece exhibition suggests that its curator, Adriano Pedrosa, will embrace the miscomprehensions that are commensurate with translation, the reality is that everything will be explained to you. No space will be left for misunderstanding or its correlate, interpretation. The frustration of this exhibition is not that of the exile who, in a strange land, is unable to make sense of their surroundings but rather that of the tourist who is prevented from straying beyond the Potemkin village in which everything has been arranged to illustrate a point.

This is not to say that there are no good works in the exhibition. There are many, and Pedrosa should first be credited for bringing so many artists onto the stage whose names might be unfamiliar to visitors and for the genuine pluralism of his selection. There are early hints of a more expansive version of the idea of “foreignness” than the experience of being outside one’s homeland, and a group of paintings by Emmi Whitehorse at the opening of the Arsenale introduce what promises to be a rewarding theme. These ostensibly abstract compositions are pictorial representations of the artist’s native landscape in the US Southwest, incorporating the inconsistent flow of time and resembling a musical score more than a photographic image.

In a similar vein is Dana Awartani’s restorative installation of red and orange hanging silks, each “medicinally dyed” according to Ayurvedic methods (Come, let me heal your wounds. Let me mend your broken bones, 2024). For all the soothing effects of the light strained through these screens, closer inspection reveals that each strip is scarred with the patches of rough stitching made to repair rents representing sites in the Arab world destroyed by conflict. These works do not challenge the boundaries between figuration and abstraction—or indeed linear time and three-dimensional space—so much as disregard them as the artificial constructs upon which an entirely different way of seeing depends. Here is “foreignness” as not just physical displacement but as the alternative constitution of perceptual frameworks.

The problem is that the show is itself unwilling to make a comparable jump. It is hamstrung in this respect by a determination to draw attention to the categories it claims to be dismantling, a paradox most apparent in its conventional museological arrangements and neatly encapsulated by the inclusion on every wall text of the artist’s birthplace and residence.2 The constant reminder that these works are products of cultures foreign to the imagined viewer—and I could not escape the sense that there was an imagined viewer—makes it very difficult to move beyond the structures of identity and attribution that one might expect the exhibition to disrupt. Beneath this lurks a latent presumption about what is foreign to whom—or what is canonical and what is extraneous to it—that is revealed by the exhibition’s excessive protestations. Take the description of Santiago Yahuarcani’s paintings as “neither derivative nor dependent on Western art history.” This only begs the question, who said that they were?

The most memorable work in the show is that which succeeds in slipping these binds. Bouchra Khalili’s multiscreen installation of maps on which hands trace the lines of their owner’s migration (The Mapping Journey Project, 2008–11) is affecting precisely because each subject tells their own story. A series of textiles by Claudia Alarcón with the collective Silät are among a number of abstractions to remind visitors that creative practice is not only a means of carrying forward a community’s specific cultural heritage but also a mechanism for the generation of aesthetic experiences that can travel beyond the circumstances of their production (a canvas by Etel Adnan supports the point). Evelyn Taocheng Wang’s homages to Agnes Martin (notably Colored Cotton Candies and Imitation of Agnes Martin, 2023) are possessed of a lightness that makes them pleasingly difficult to pin down. It is to their credit that, while it would be easy to write about these paintings in the buzzy terms of authenticity, contested authorship, or hybridity, it would be insufficient to communicate their effects.

Here is a glimpse of “foreign” as signifying something closer to “uncategorizable” than “other,” and I found myself wishing that the curators had resisted the urge to compartmentalize that sees works arranged into groups united by some formal or biographical affiliation. This legislates against the production of those unpredictable effects that come from placing works into unexpected or counterintuitive relations, and feels symptomatic of a desire to keep a leash on the show’s meaning. Indeed, for all that the stated intention of the exhibition is to destabilize the idea of both “foreignness” and its flipside of “familiarity,” it rarely succeeded in disordering my experience of the world to the point that I felt myself to be a stranger within it. The arrangement of the exhibition places the visitor squarely at the center of a global culture, representatives of which are convened for their appreciation. The otherness of these works is so insistently foregrounded as to constrain their potential to estrange me—the viewer—from myself.

The clearest expression of the decentering potential of art remains Arthur Rimbaud’s “I is another,” and it might be because poetry is so well adapted to using a shared medium to express feelings exceeding its conventions that I found myself drawn to works operating at the points at which language breaks down. Onto the hunks of marble, granite, and quartzite that comprise her sculpture series “Scritture” [Scriptures] (2020–23), Greta Schödl has handwritten the words that signify the rocks in Italian—respectively marmo, granito, and quartzite—in repeating lines that fill the flat surface with characters, burnishing the holes at the center of the initial “q” or conclusive “o” with gold leaf to create a visual rhythm. This doesn’t read like an Adamic act of naming so much as a recognition of the insufficiency of the word and the concept it circumscribes to fully account for reality. The failure of language here breaks open the world, insisting that the viewer attend to the living strangeness of even the most inert material. It’s a little like the experience of repeating a word so many times that it not only loses its conventional meaning but becomes music.

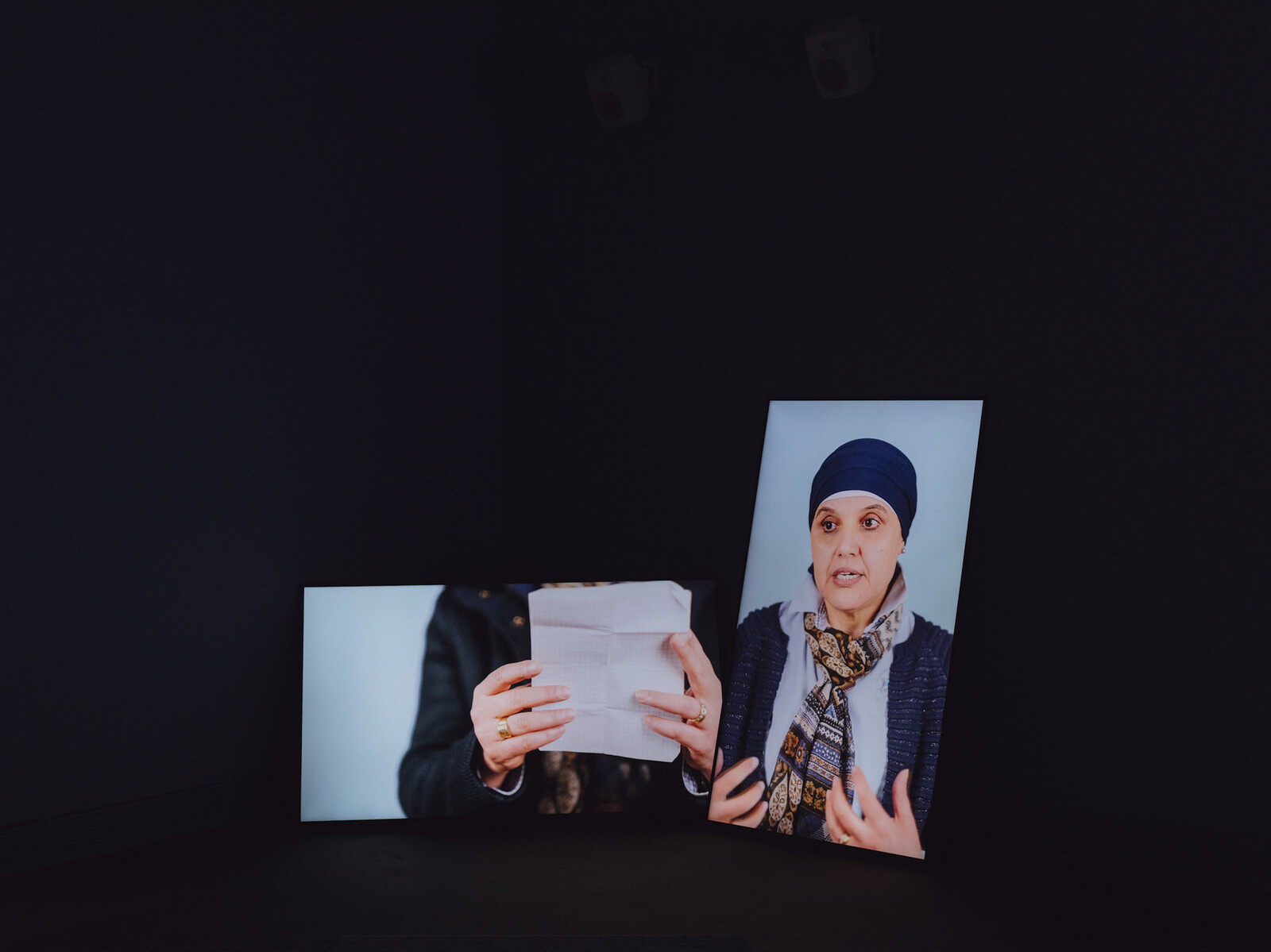

This emptying out of language into music also animates Gabrielle Goliath’s exceptional multi-screen video installation Personal Accounts (2024), in which the survivors of patriarchal violence relate their experience to camera against a monochrome blue background. Yet their words are withheld and their stories pared down to the moments at which their throats catch or they are forced to take a deep breath, producing a hubbub of inarticulate sounds overlaid by a single melody sung a cappella. It is an extraordinarily moving assertion of the liberatory potential inherent in the creative failure of our conventional forms of articulation, and for the value of artistic expression more generally.

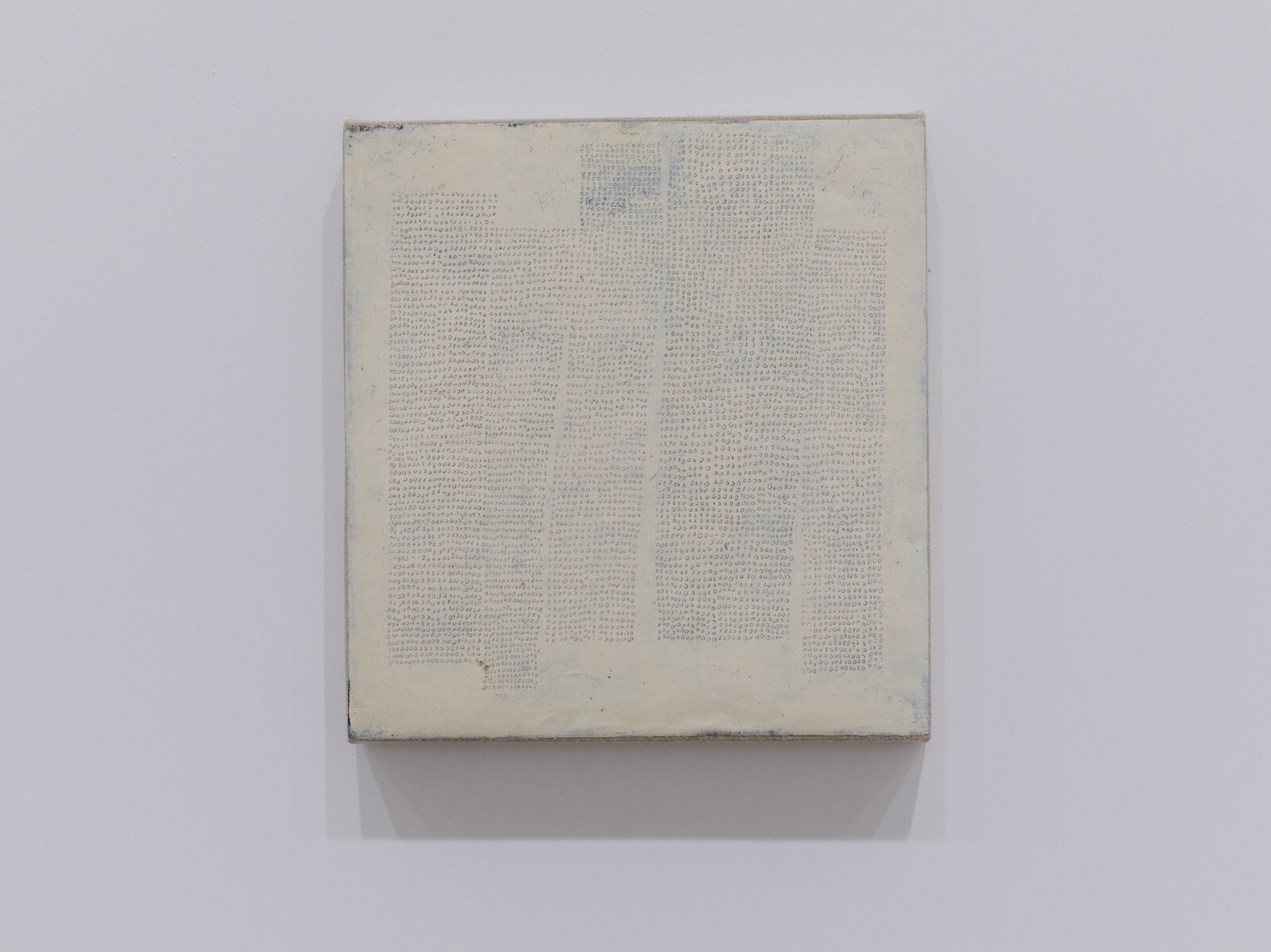

That legibility is not consistent with significance is driven home by Romany Eveleigh’s mesmerizing paintings. Consisting of repeated O’s scratched into white paint, they call to mind a passage in Anne Boyer’s Garments Against Women (2019) reflecting on Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s justification for the intellectual inferiority of women. Observing a little girl who would “write nothing but O’s; she was always making O’s, large and small,” and who gave up writing once she saw herself in the mirror, Rousseau concludes that linguistic facility was secondary in women to the desire to be beautiful.3 Eveleigh’s paintings might be taken as support for Boyer’s counterargument that these O’s constituted the girl’s secret language and infinitely expanded literature, “each O also an opening, a planet, a ring, a word, a query, a grammar. One O could be an eye, another a mouth, another a bruise, another a calculation.”

The girl stopped writing when she looked in the mirror not because she admired herself but because her O’s were written backwards. She was reading what she had written, the hidden meaning of which must always elude Rousseau, might have been designed to defeat his reason. Eveleigh’s paintings also evade control and categorization, might need a mirror or a codebook, carry meanings that cannot be corralled into conveniently representative categories, might like the girl’s writing be translated as “I understand the proximate shape of the fountain” or “Apples are smaller than the sun.” These are what Boyer calls “revolutionary letters in the code of Os,” and in this unbound language can be found a radical freedom that the intellectual architecture of this exhibition too often closes down.

This is the first in a series of responses to the 60th Venice Biennale by e-flux Criticism. Reviews of selected national pavilions, as well as appraisals of its overarching themes, will be published over the coming days and weeks.

The iterations of Claire Fontaine’s ongoing series exhibited at the Biennale pointedly replace the masculine “i” of stranieri, or foreigners, with a backwards “e.”

The exhibition literature also takes great pains to remind viewers how many of the artists in the exhibition have not shown as part of the Biennale before. In itself this fact is laudable, but its inclusion at the bottom of each relevant artist’s wall text only serves uncomfortably to suggest that novelty was among the criteria for selection.

Quotes taken from Anne Boyer, Garments Against Women (London: Penguin, 2019), 98–100.