If the ghosts of Liszt and Chopin have become fluent English speakers while in the land of the dead, isn’t it strange that they have accents? In fact, an accent is just like a composer’s signature style: a small detail that reveals the origin of a given piece. Style was what experts looked for when examining the scores written down by medium Rosemary Brown for confirmation of life after death. But why should a dead composer have the same style as when they were alive?

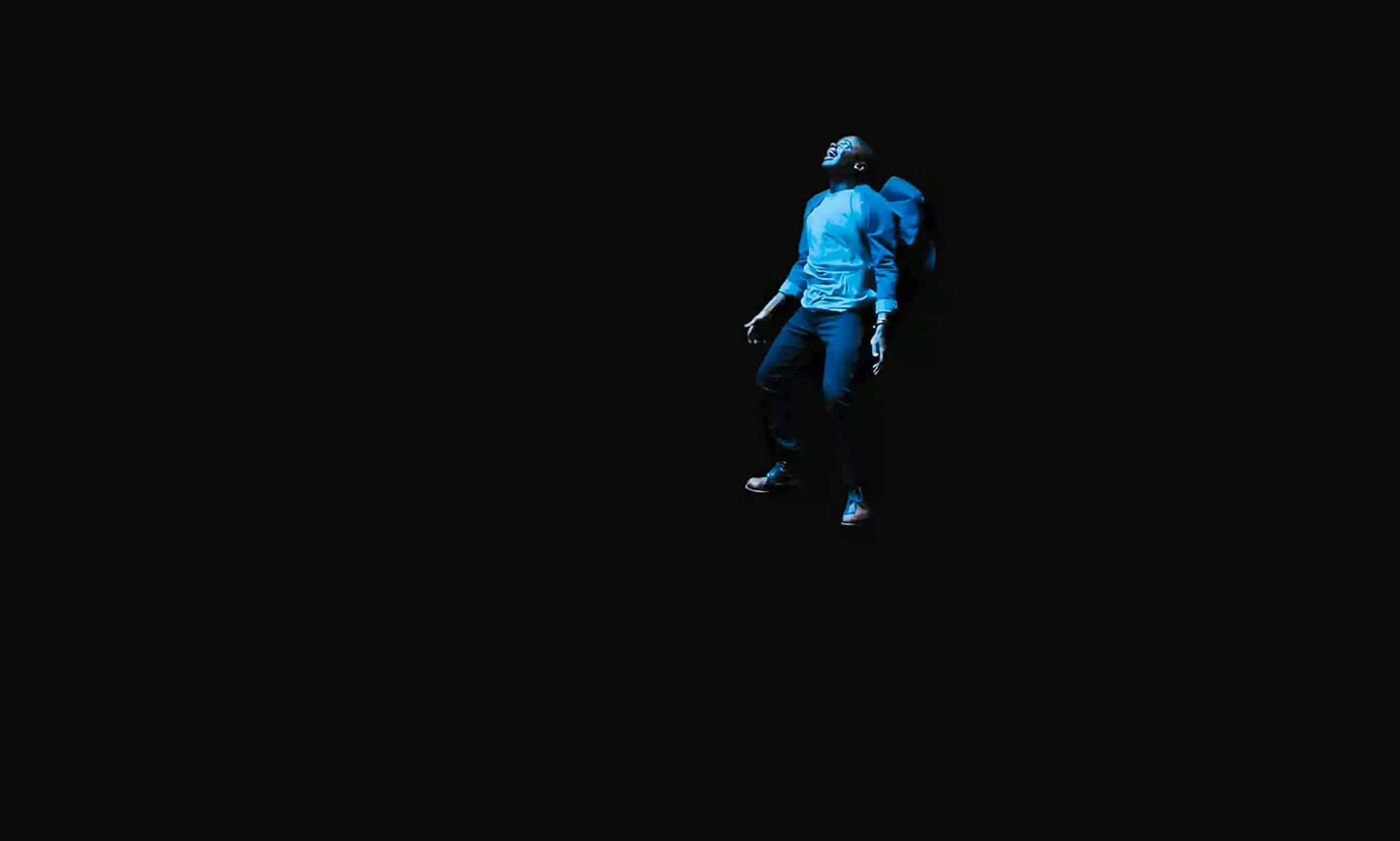

A photograph of a Yangtze River dolphin, commonly known as the baiji, was printed in one of my textbooks when I was a pupil in Dalian, China. I remember staring at a small white back submerged in a tideless pool. It was 2007, and our teacher informed us that the animal we were looking at was near extinction. The last known baiji had died in captivity five years prior. When I saw the photograph, I did not realize I was looking at a ghost—not just of an individual animal, but of an entire species.

Only the living can visit the dead, not the other way around. We’re there when George Washington buys a slave. We’re there when a tree bears strange fruit. We’re there in the gas chambers, or when Winston Churchill starves to death millions of Indians. And as we in the present are in the past, we are also haunted by those in the future, those not yet born.

Louis Henderson: Ouvertures

Takeover: Online discussion with May Adadol Ingawanij, Riar Rizaldi, Ephraim Asili, Tiffany Sia, and Sriwhana Spong

Online discussion with May Adadol Ingawanij, Ephraim Asili, Tiffany Sia, and Sriwhana Spong

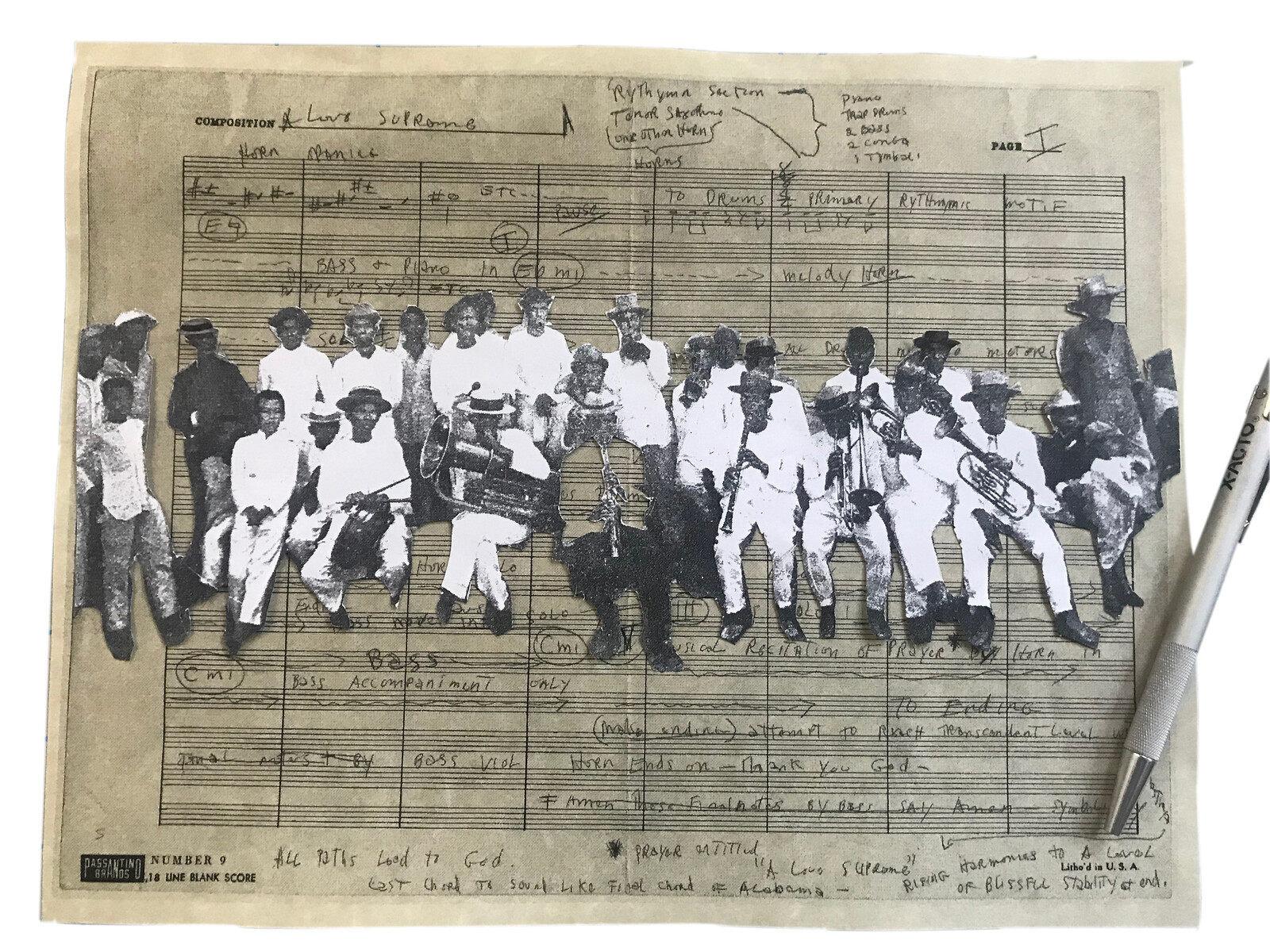

I’d gotten good enough at listening to the dead that I could call them in. Not like they’d come every time I called, but time to time they’d come. And that’s how I’d heard stories from men and women who lived in other times and places. Ancestors. Not long ago. Some of them in California, during the twenties and thirties.

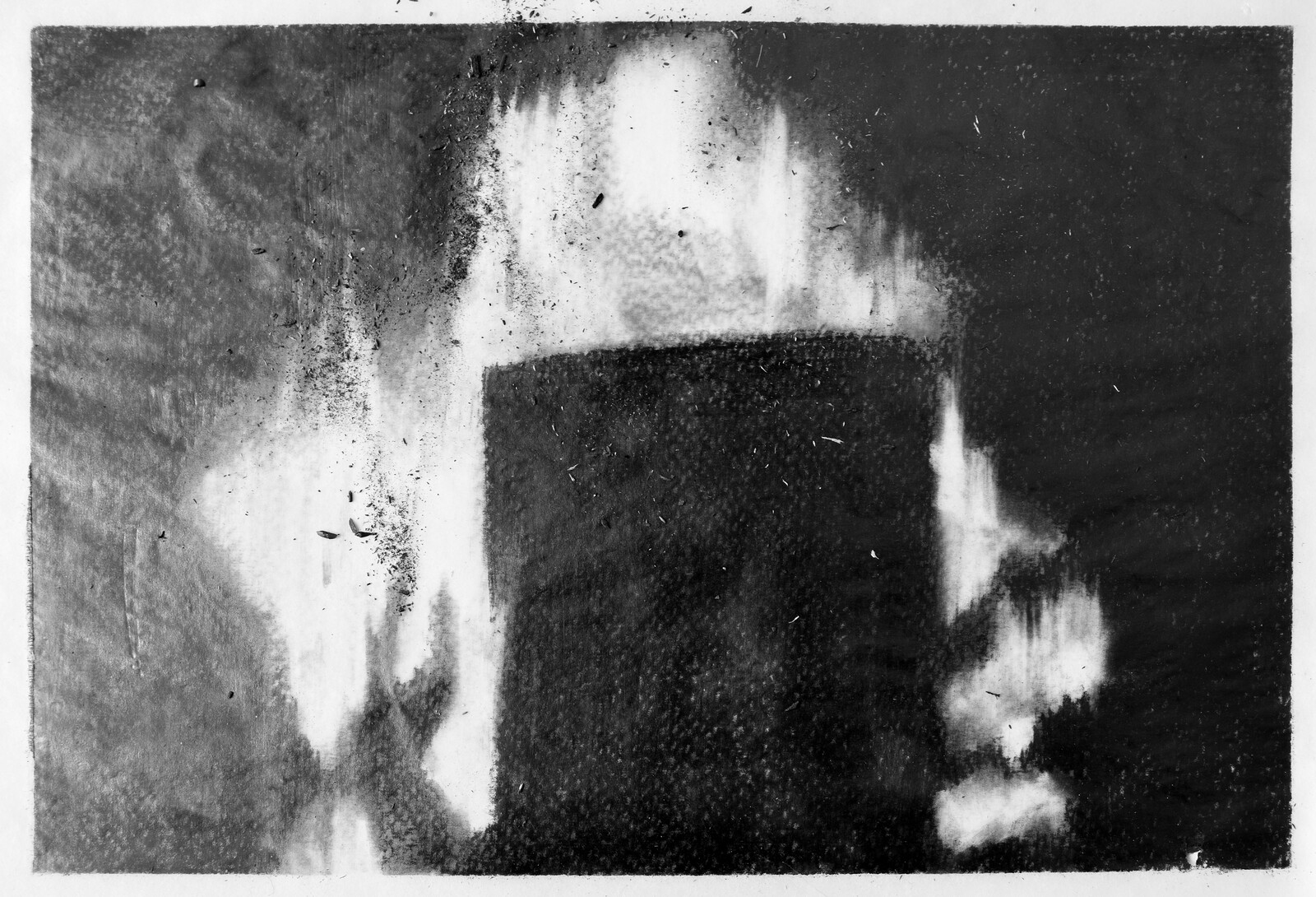

let us investigate the notion of art after the end of the world, and the two figures this proposition conjures up: the figure of the post-, something after the event; and the figure of the main event itself, the end of the world, or if you will, the apocalypse. If there is to be something like art after the apocalypse, this would mean that something is still present, in whatever form, or that something is still being presented and produced, and possibly made public, whether as a form of signification or de-signification. That something (i.e., art) has a meaning or being after the end of the world, whether symbolically or in actuality. Let us first investigate the latter: that the world has in fact ended, but there is still art, still cultural production. By whom is it produced if the world has ended? What could it possibly mean, moreover, to produce art and culture after the end of the world, and thus, presumably, after the end of both the natural and the cultural world, of both bios and zoë, as it were? Would there still be life, or even afterlife, at all? What would it mean to be alive after the end, either as survival or beyond death? Would such a subject still be human, or perhaps rather inhuman or even post-human? In any case, the suggestion of an art after the end of the world implies that there is someone around after the end, whether as producer or receiver: that there is transmission of some sort or another, intentional or unintentional.