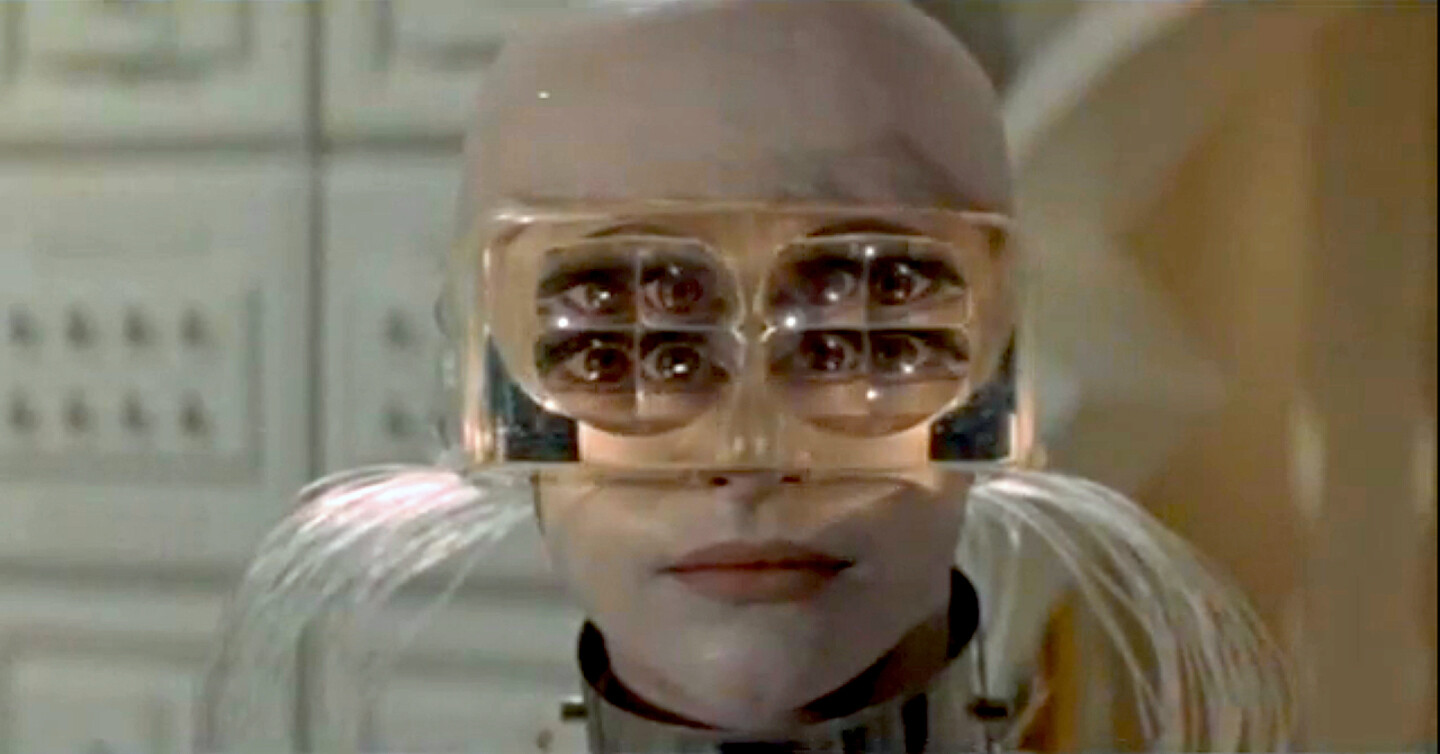

Methodologically speaking, it might be said that all of Ilya and Emilia Kabakov’s installations are in some way or another connected with a special structured experience of space, echoing the transformations of the starry sky. But there is one installation in which the sky also becomes the center of gravity. We are talking about perhaps their most famous installation, The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment, first shown in the Kabakovs’ Moscow studio in 1985. The viewer is presented with a room in a communal apartment that has been sealed off by investigators. The room’s resident has, with the help of a homemade device, escaped Soviet reality and is hiding in the sky.

Cosmists regard progress not as a goal or an end in itself, but rather as a necessary sacrifice that is an integral part of humanity’s struggle to survive and evolve. Real development, they believe, can only begin after humanity triumphs over death and learns how to resurrect the dead. This vision suggests that the future becomes the reconstruction or restoration of the past, and the arrow of time bites its own tail.

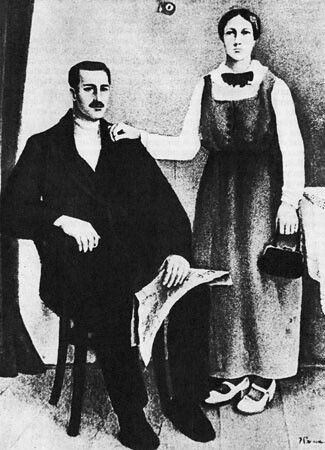

Almost a decade before the revolution, Bogdanov depicted a postrevolutionary Marxist museum in his science-fiction novel Red Star from 1908. “I imagined there would be no museums in a developed communist society,” exclaims Bogdanov’s astonished protagonist upon his arrival on Mars, home to a highly advanced Communist civilization. The museum has indeed survived, but its function has been modified. The museum is no longer a bourgeois ghetto, a repository for all the delusional hopes for the resolution of social contradictions. The liberating force of proletarian revolution has dissolved class divisions as such, and art, once an autonomous professional sphere, has been integrated into the everyday life and work of humanity.

How might the contents of the museum be reanimated so as to transcend even the social and physical limits imposed on humankind?

_-_Volga_Boatmen_(1870-1873)WEB.jpg,1600)