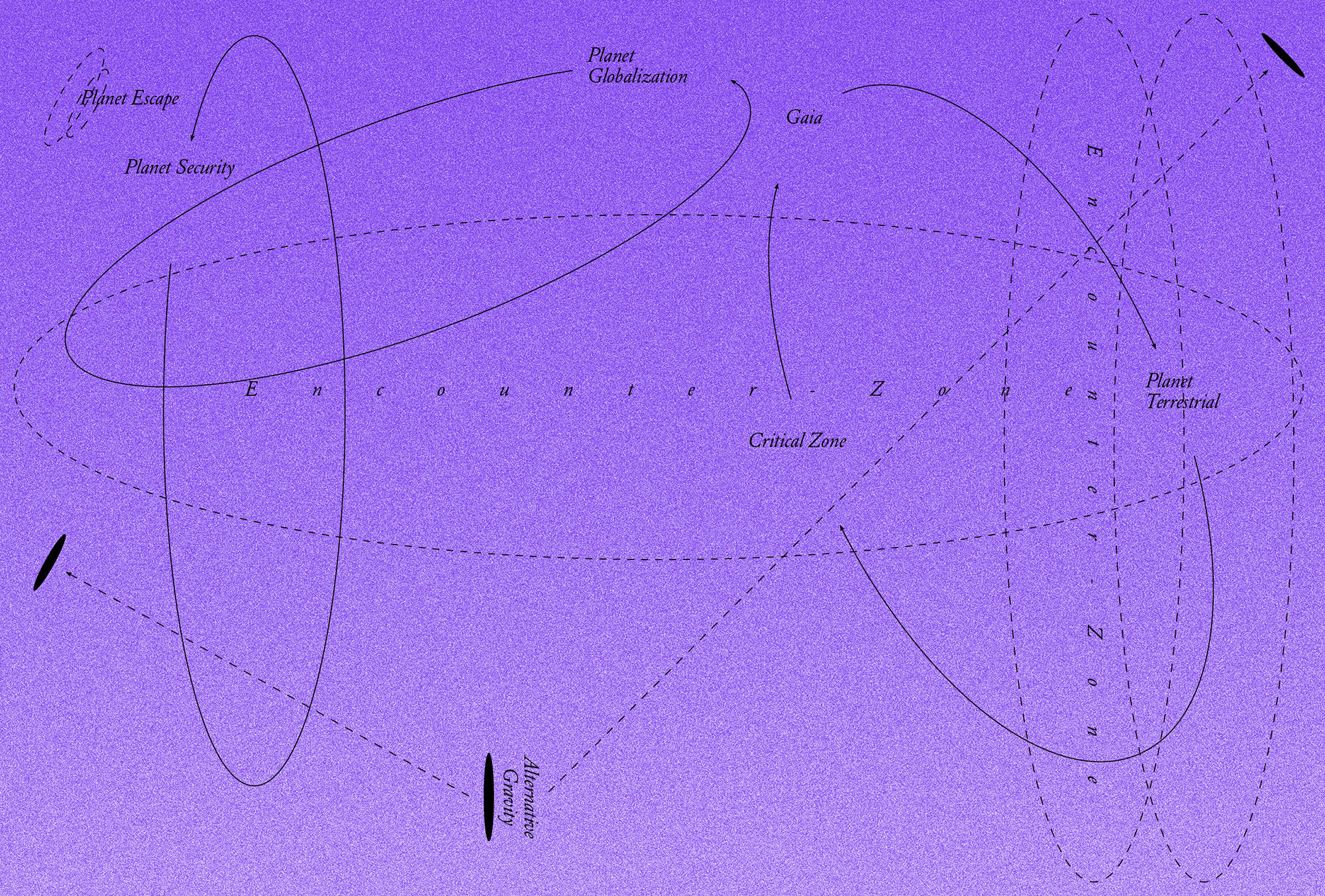

Eternity is timelessness; it is nonliving death. Life is finite, temporary, but it is meta-nonliving. The living can see/observe the nonliving (and the living), while the nonliving cannot see either the living or the nonliving. If 2D images derived from RNA/DNA sequences are “pictures of the world” recorded by living matter, then perhaps another kind of life-form, regardless of its molecular structure, might perceive the world in a similar way. Its “pictures of the world” might correspond to those recorded and saved within RNA/DNA. In other words, if the two living forms are structurally different, having different or even unrelated material properties, they might still perceive the world in a similar way. Temporariness is the price life must pay in order to be able to see the world.

Ghosts

In times where elusive, invisible forces seem to be ruling our existence, to reclaim the presence of ghosts is to question both the epistemologies of the real and the politics of the visible. But who or what is perceived as ghostly? What is immaterial/physical and how does our human perception construct its limits? Is the spiritual a metaphysical dimension of the self or just an extension of our physicality? This reader examines the countless dimensions of ghosts and the possibilities that they enable. Considering the languages, gestures, spaces, and politics invoking ghosts, the following essays challenge not only notions of life, absence, liminality, consciousness, agency, and existence, but moreover the immaterial conditions of world–making.

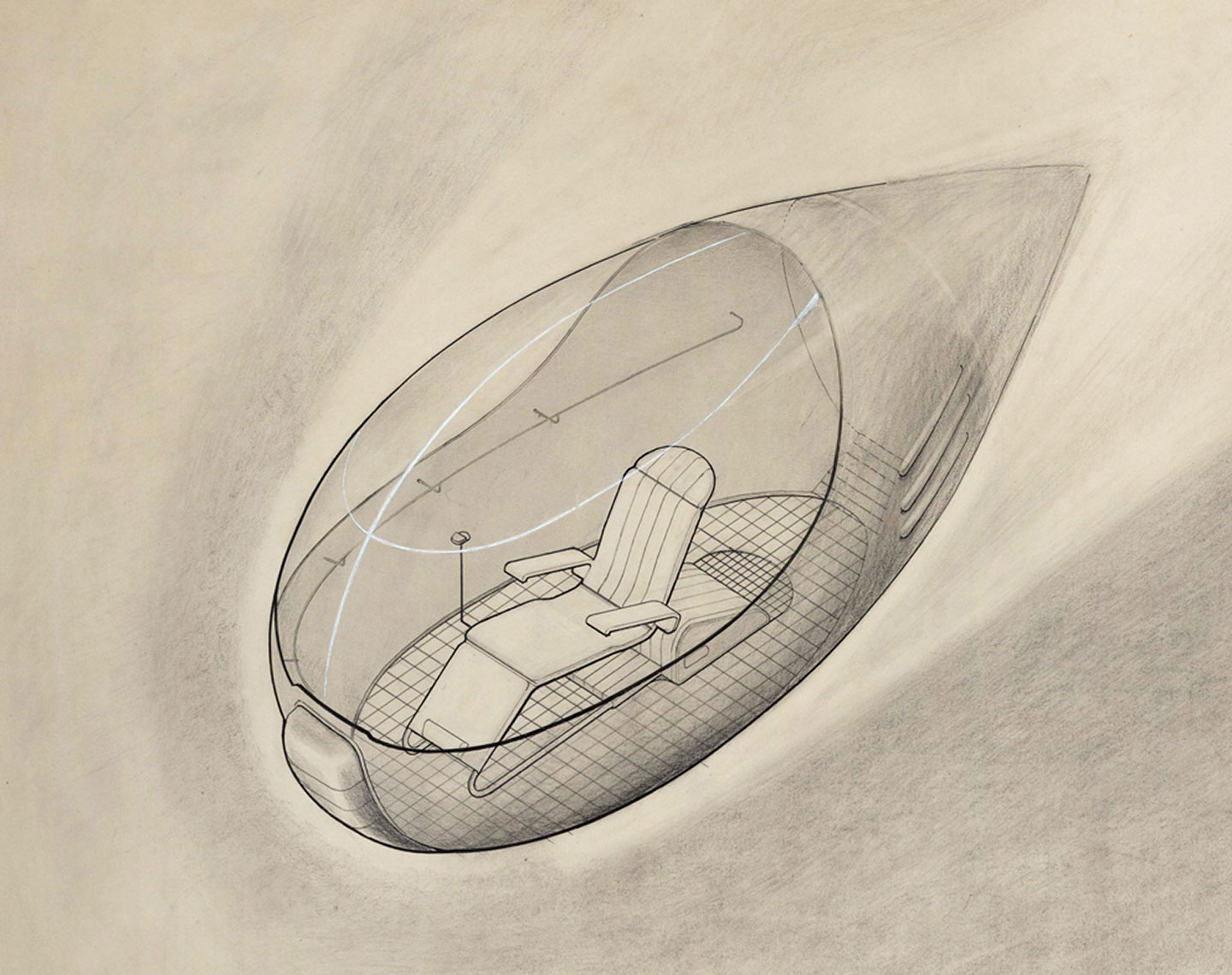

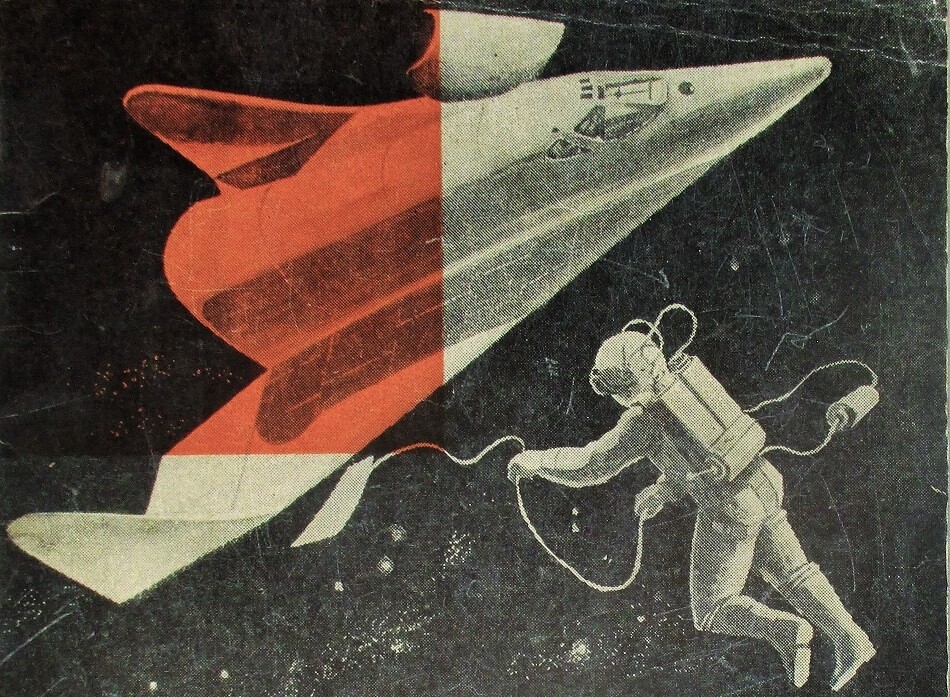

Cosmist thinkers founded the “organization of world-transformation”—an organization that was meant to encompass all the types of humanity’s creative activity, all spheres of its theoretical and practical application—on the creative principle found in art. Art opens before humanity an opportunity to move away from the present instrumental, technical progress, which acts upon nature only from outside, by use of mechanisms and machines, to a new, mature type of progress that would be organic, that would transform and spiritualize the world through a living, non-mediated touch.

I’d gotten good enough at listening to the dead that I could call them in. Not like they’d come every time I called, but time to time they’d come. And that’s how I’d heard stories from men and women who lived in other times and places. Ancestors. Not long ago. Some of them in California, during the twenties and thirties.

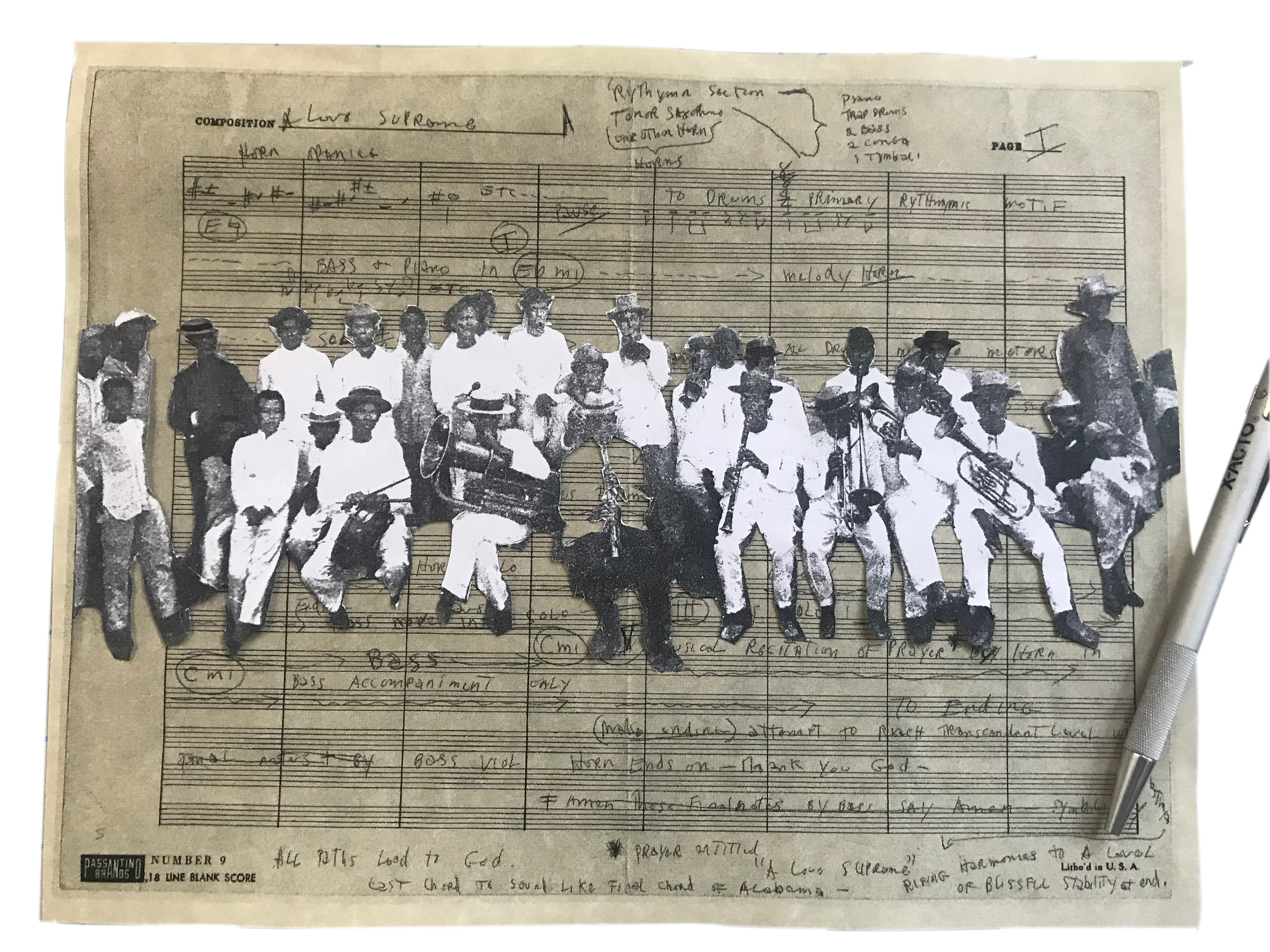

There is said to be a universal hum. An imperceptible vibration producing a sound ten thousand times lower than can be registered by the human ear. It can be measured on the ocean’s floor, but its source is not exactly known: perhaps the hush of oceanic waves, perhaps the turbulence in the atmosphere, or the far bluster of planetary storms.

These spirits are tenants of nothing jointly, temporary inheritors of pages 276 and 277 of an old paleology. They sometimes hold a life like a meeting in a detention camp, like a settlement without a stone or stick, like dirty shelves, like a gag in the mouth. Their dry goods are all eaten up already and their hunger is tenacious. This spirit doubling and quadrupling, resuming, skipping stairs and breathing elevators is possessed with uncommunicated undone plots; consignments of compasses whose directions tilt, skid off known maps, details skitter off like crabs.

One, two, three, four—and a plant framed in the middle of the shot is ripped out from the ground with its severed roots dangling in midair. The seeming oxymoron of a “taxonomy of monsters” can also be displaced and reencountered in the monstrousness of taxonomies as such; they sever specimens from the fluid integrity of the environments they inhabit, and which inhabit them, in order to monstrare: reveal, show, demonstrate. They cut apart the world, just as surgeons cut into the flesh. And what is more uniquely cinematic than the cut? What aspect of film more monstrous?

With the cybernetization of the world, both the human and the divine are downloaded into a multitude of tech objects, interactive screens, and physical machines. These objects have become genuine crucibles in which visions and beliefs, the contemporary metamorphoses of faith, are forged. From this standpoint, contemporary technological religions are expressions of animism.