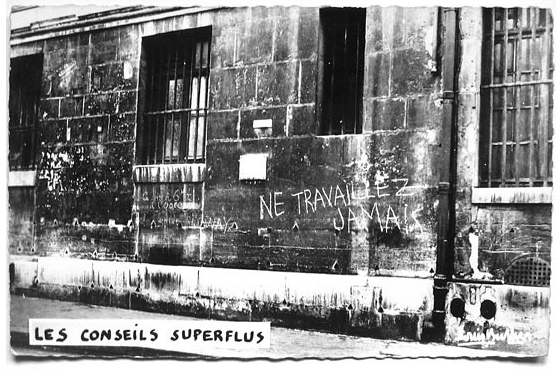

Strike

The strategy of withdrawing productivity has historical roots in labor politics, anti-colonial activism, and feminist practices, characterizing official as well as wildcat workers’ strikes, public protests, and more subtle acts of refusal in private and domestic spaces. But what does it mean to “strike” when work itself is increasingly fragmentary and immaterial, disconnected from sites of production, while also permeating every facet of life? These texts explore individual and collective refusals of labor, abstract strikes, and strike work within and beyond the economies and ecologies of contemporary art. Suggesting the critical potential of unproductivity, immobilization, and refusal, they also highlight the activity of those on strike to create conditions under which progressive alternatives can flourish.

Imagine experts in the world of art admitting that the entire project of artistic salvation to which they pledged allegiance is insane and that it could not have existed without exercising various forms of violence, attributing spectacular prices to pieces that should not have been acquired in the first place. Imagine that all those experts recognize that the knowledge and skills to create objects the museum violently rendered rare and valuable are not extinct. For these objects to preserve their market value, those people who inherited the knowledge and skills to continue to create them had to be denied the time and conditions to engage in building their world. Imagine museum directors and chief curators taken by a belated awakening—similar to the one that is sometimes experienced by soldiers—on the meaning of the violence they exercise under the guise of the benign and admitting the extent to which their profession is constitutive of differential violence.

Agents of artistic circulation mistake the decision to withdraw one’s labor or participation for idle disengagement. The illusion of political agency granted by global artistic circulation underpins this ideology. In contrast to these false accusations, striking art workers engage in artistic self-organization, the highest form of social creativity, which produces new social assemblages that sustain artistic creativity beyond its ossified forms. Only when reinvigorated by strikes, boycotts, and occupations do institutions of the commons emerge and provide ground for art as a practice of freedom. Far from destroying circulation, the refusal of art workers in moments of productive withdrawal allows for its resumption at some point in the future and under better terms. Without moments of collective refusal, there would be nothing to circulate under the name of art but luxurious objects, emptied of sense and value.