Rebirth

“I’m telling you this

we needed to stop.

(…) We all felt it

that it was too furious,

our frenzy. Being inside of things.

Outside of our selves.

(…) We needed to do it together.

(…) And there is gold, I believe, in this strange time.

Perhaps there are gifts.

(…) A common fate

holds us here.

(…) we will return with expanded awareness.

(…) Our hand

will be more delicate in the doing of life.”

—Mariangela Gualtieri, “March the Ninth Twenty Twenty”

The world we left can be reborn from these words and texts.

But what does vulnerability actually mean? Is it being able to acknowledge a state of pain or insecurity, embracing the feeling of coming undone? I feel that it’s something I’ve tried to hide from others and from myself. At the cost of headaches, a bloated stomach, the inability to articulate a sentence. A mental-physical feeling of paralysis. I now suspect that people spend a lot of time and effort hiding in this way. Could I overcome my terror of falling apart if I allowed myself to rely on others, on you? Or should I be a “cruel optimist” and create hopeful and positive attachments, in full awareness that they will not work out?

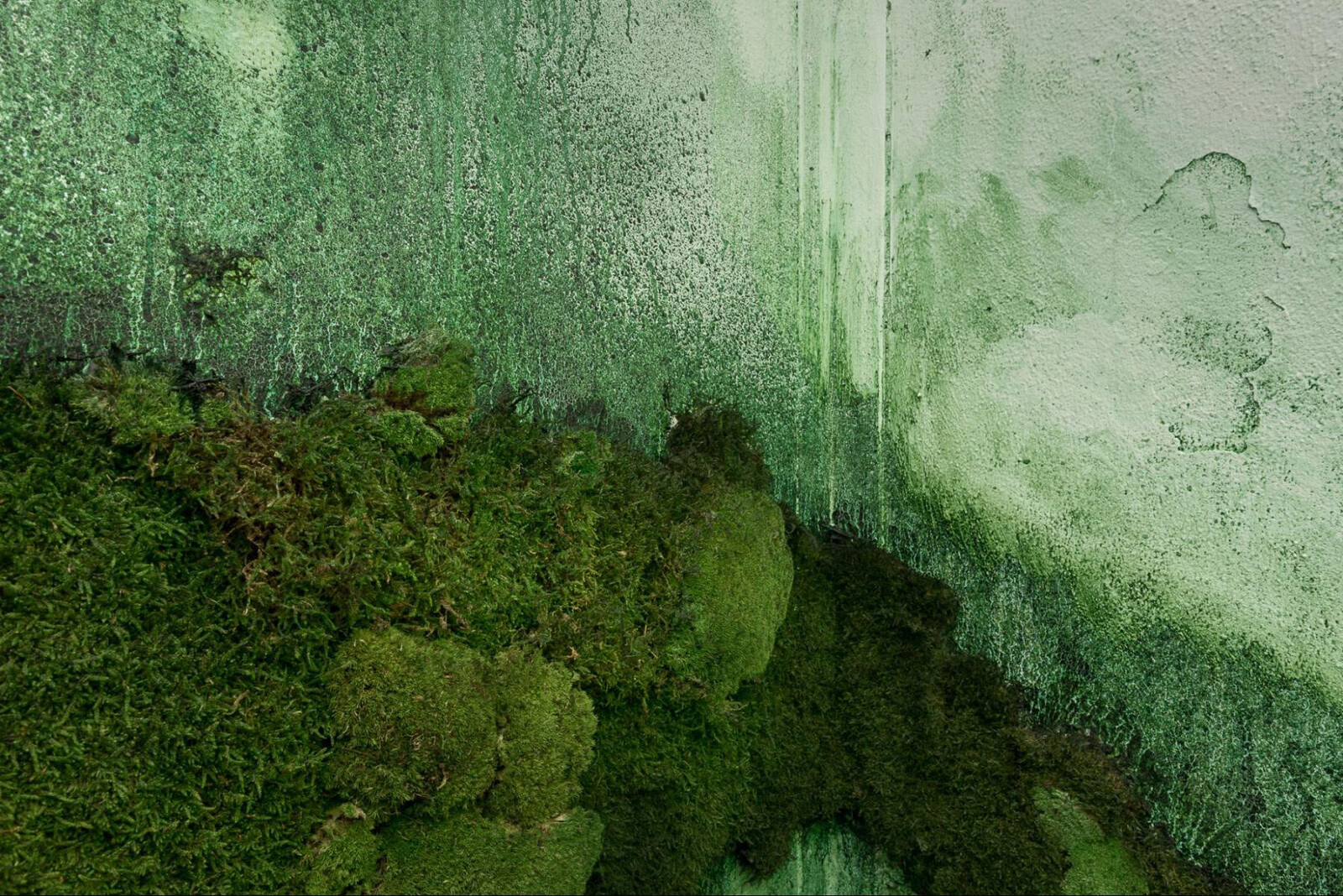

The mediated, sentient, and intelligent plant potentially invites us to think about nature, plants, technology, and ourselves-as-humans in different ways. As plants in particular are revealed as agentic, intentional beings, the mediated plant potentially invites us to develop more caring, attentive, and communicative attitudes toward the vegetal. In this way, the mediated plant can push us forward in the urgent “struggle to think differently” that Val Plumwood called us to join. Perhaps the mediated, sentient, intelligent plant can help us to queer nature, to queer botanics, to queer ourselves-as-humans as we “go onwards in a different mode of humanity.” But why to queer? Why not “simply” to “decolonize”?

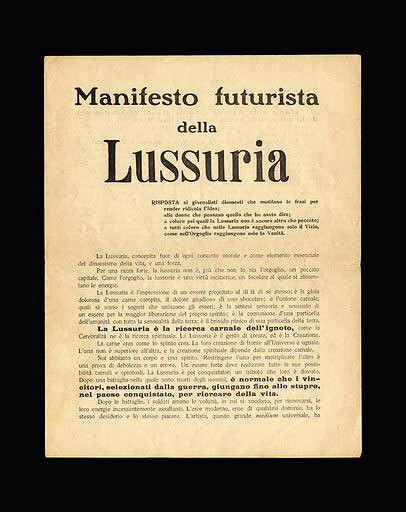

Free love and camaraderie were at the core of Kollontai’s thinking, for her novels and essays describe love as a force that frees one from bourgeois notions of property. As an influential figure, a rare woman in the Bolshevik Party leadership, and commissar for social welfare in their first government, she not only set up free childcare centers and maternity houses, but also pushed through laws and regulations that greatly expanded the rights of women: divorce, abortion, and recognition for children born out of wedlock, for example. She organized women’s congresses that were multiethnic in the way the young Soviet Union practiced controlled inclusion, following Western models. At the time, these were unique measures that were soon overhauled by Stalin, who did not appreciate any attempt at ending what Kollontai called “the universal servitude of woman.”