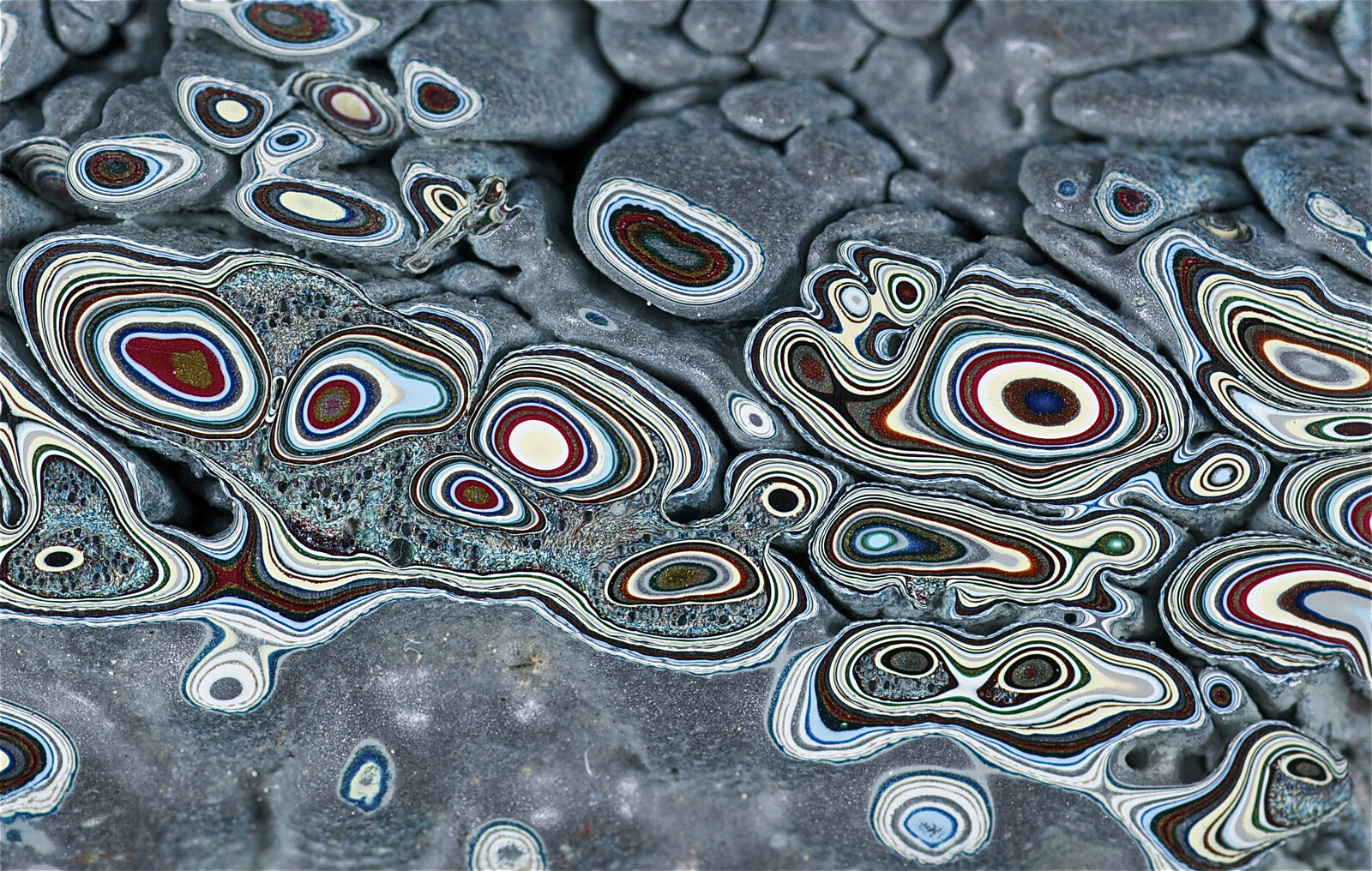

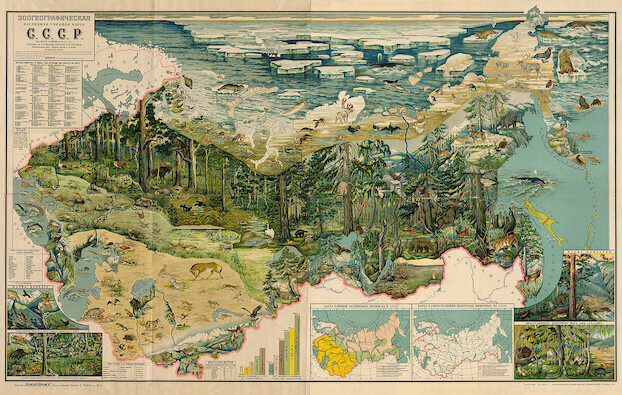

Can we resurrect the people who have not been born yet, but who nevertheless died prematurely due to environmental devastation, hunger, racism, and inequality? Perhaps by learning from Fedorov to think about time as a landscape—one that we shape in the same way that we shape the earth’s surface—we can develop a framework for thinking some of our most urgent crises.

Shadow-Time

The Coronavirus pandemic has thrown many of us into a state of disorientation, laden with uncertainties. Crossing vastly different temporal scales, our concerns range from our own immediate survival to existential questions raised by illness and death at planetary scales; from the impact that shutdowns and imminent global recession have on a personal level to the possibly longterm implications of the current reduction of CO2 emissions for planet Earth.

The Bureau of Linguistical Reality defines Shadow Time as “a parallel timescale that follows one around throughout day-to-day experience of regular time”; or “acute consciousness of the possibility that the near future will be drastically different than the present.”

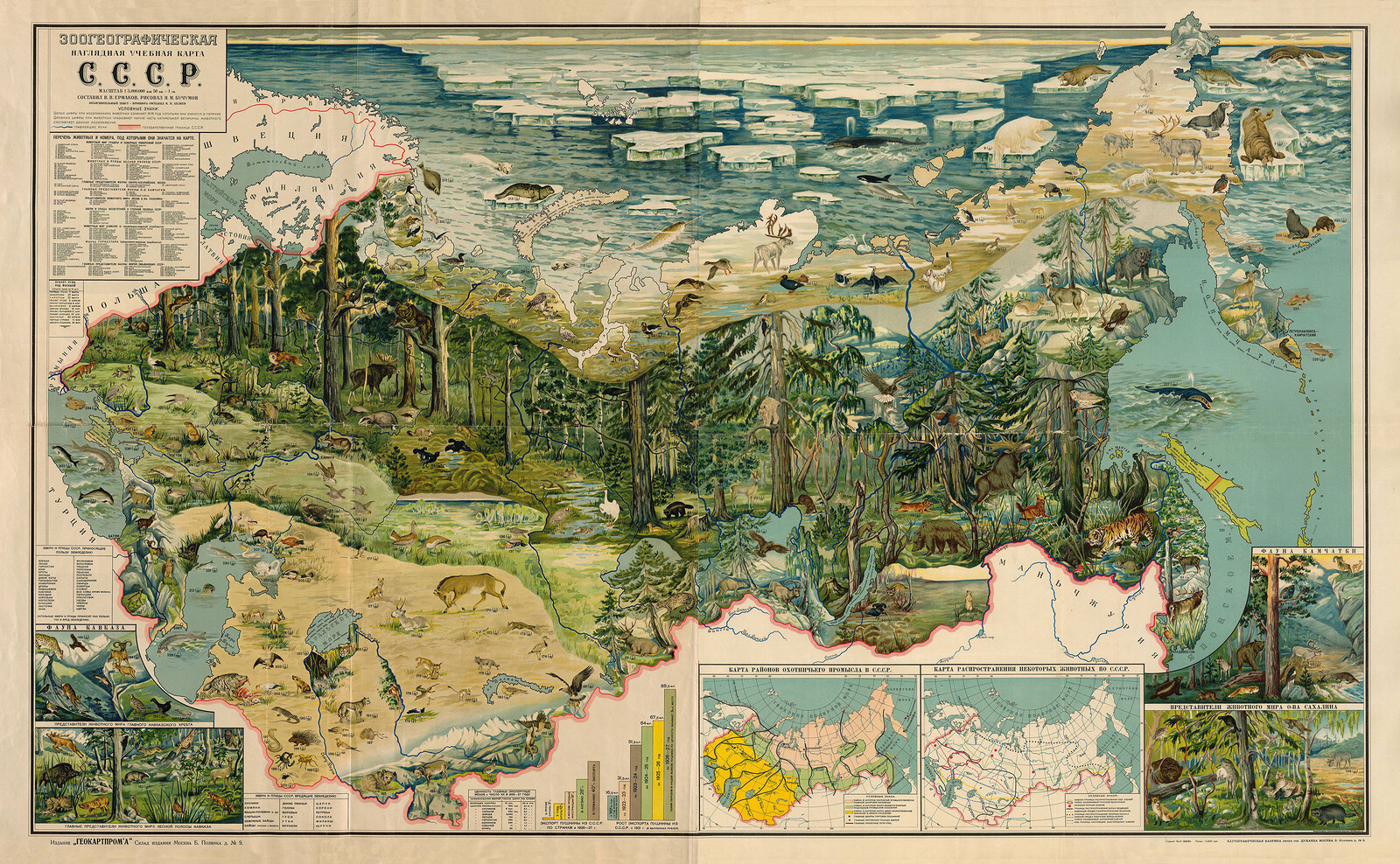

As the urgent and fast-moving crisis of this pandemic intersects with the also urgent but much slower-moving crisis of climate change, will the human experience of Shadow Time contribute to a more time-literate society? Will we humans be capable of expanding our temporal sensibilities to embrace a more poly-temporal worldview? Will we be able to deeply understand and mentally inhabit the geologic time scales at which our own human activities and actions are operating today?

Environmental collapse, global civil war, nuclear proliferation, and epidemics of panic and depression are steps towards extinction. But this is not the end of the world, since abstraction has created a world of its own, subsuming social language and prescribing the social forms of interaction.

“Life” in the phrase “Black Lives Matter” is defined as that which can be killed or which dies. It is also a measure of time, for however long we are alive is a life. Many human lives have been and are considered disposable, surplus, or without value, so the movement speaks of each life as mattering. When black life matters, time itself is altered, creating revolutionary time. These temporalities have become entangled with the crisis of earth-system time known as the Anthropocene. That time, known to geologists as “deep time,” is in crisis. And it’s a good thing too, because out of that crisis has reemerged the possibility of revolutionary time. No one has been more aware of this dynamic than the anti-black reactionary right. To be for revolutionary time, whatever one’s own personal history, is to be for anti-anti-blackness as the condition of transformative possibility.