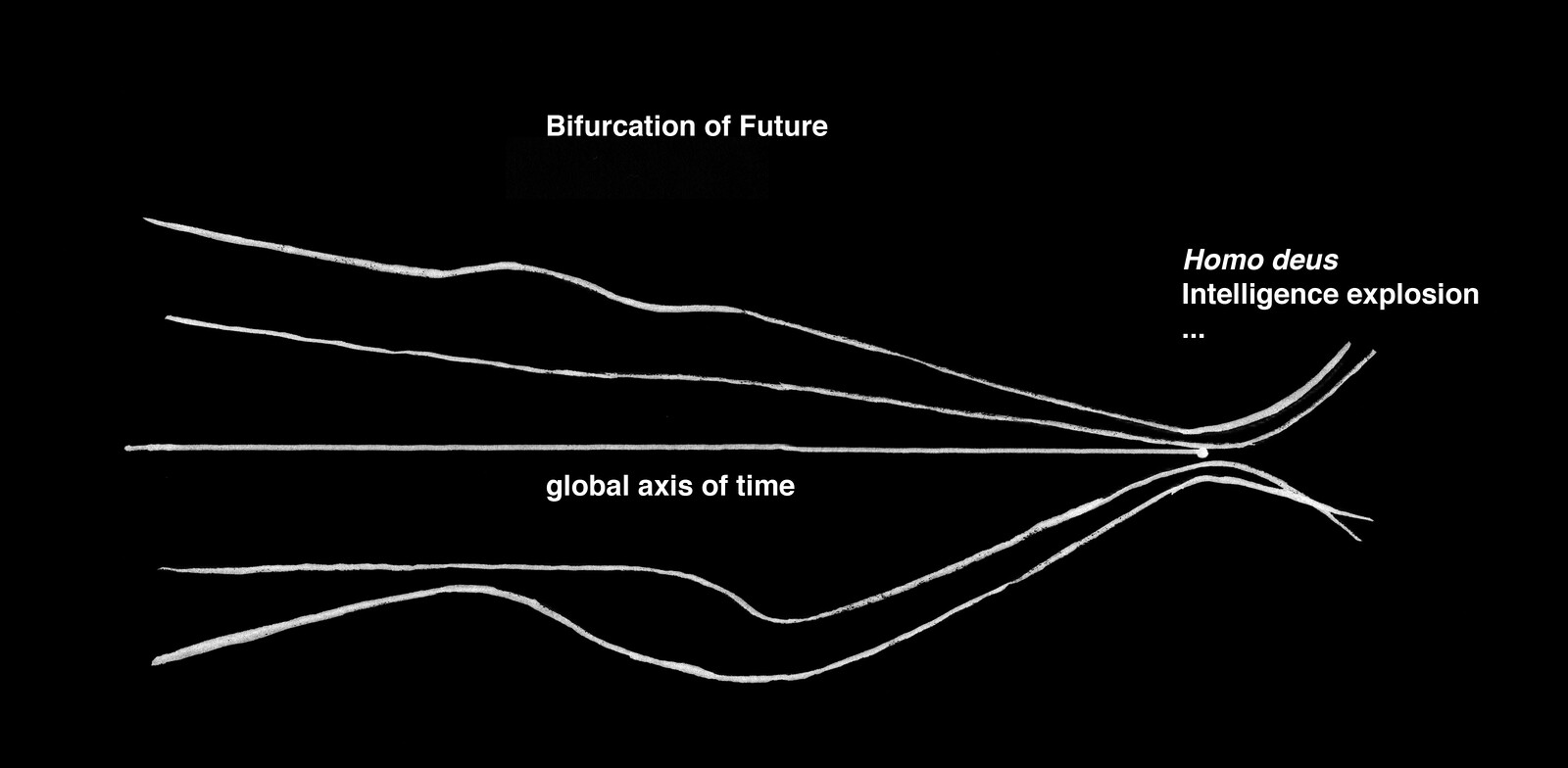

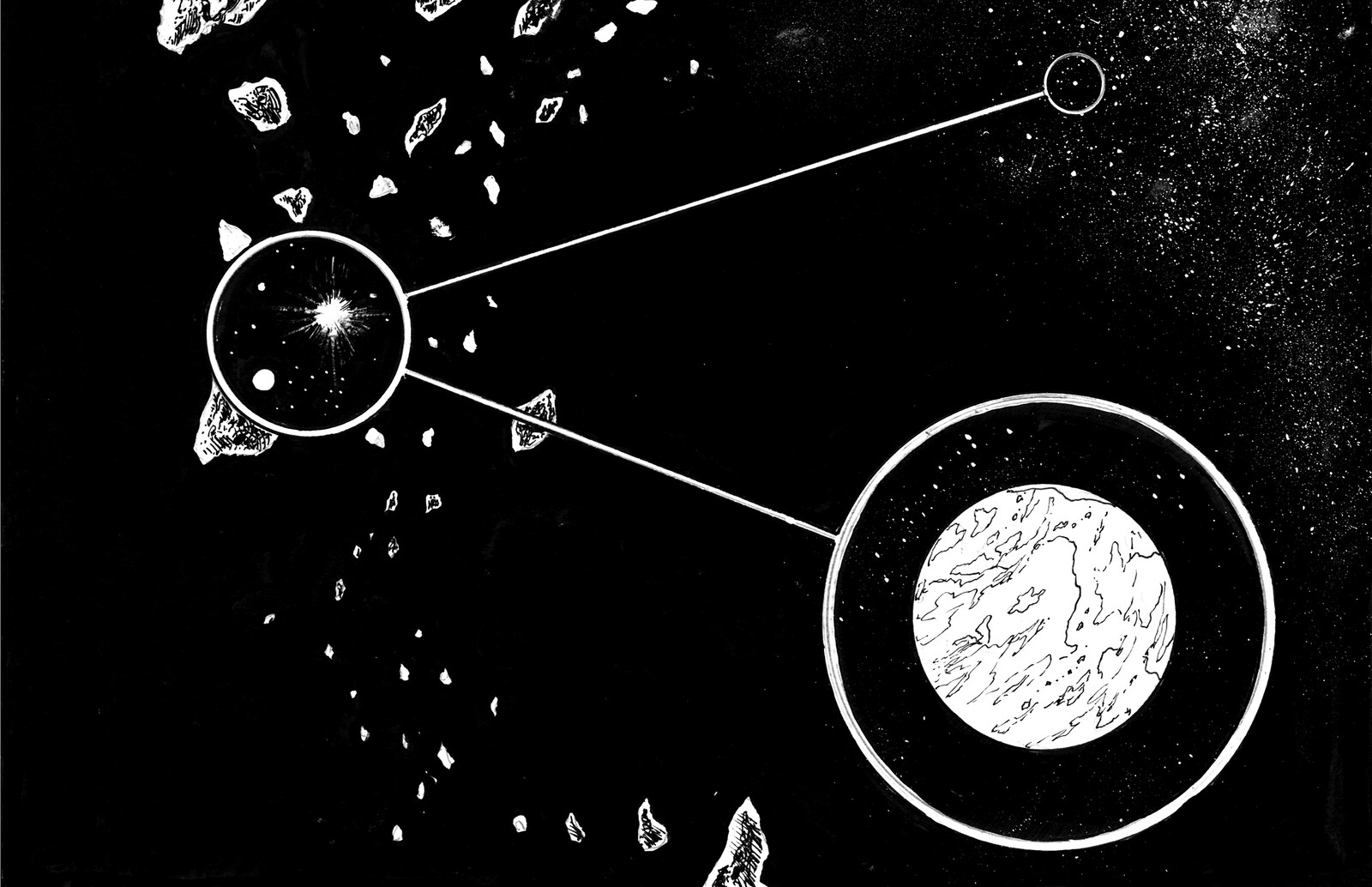

On the other hand, we may understand Kissinger’s end-of-Enlightenment claim as marking the full realization of a single global axis of time in which all historical times converge into the synchronizing metric of European modernity. It is the moment of disorientation—a loss of direction as well as of the Orient in relation to the Occident. The unhappy consciousness of fascism and xenophobia arises from this inability to orient: as a response, it offers an easy identity politics and an aestheticized politics of technology. More broadly, such a disorientation can be seen as a desirable and necessary deterritorialization of contemporary capitalism, which facilitates accumulation beyond temporal and spatial constraints. War is the technique of disruption par excellence, vastly more effective than Uber and Airbnb.

Time

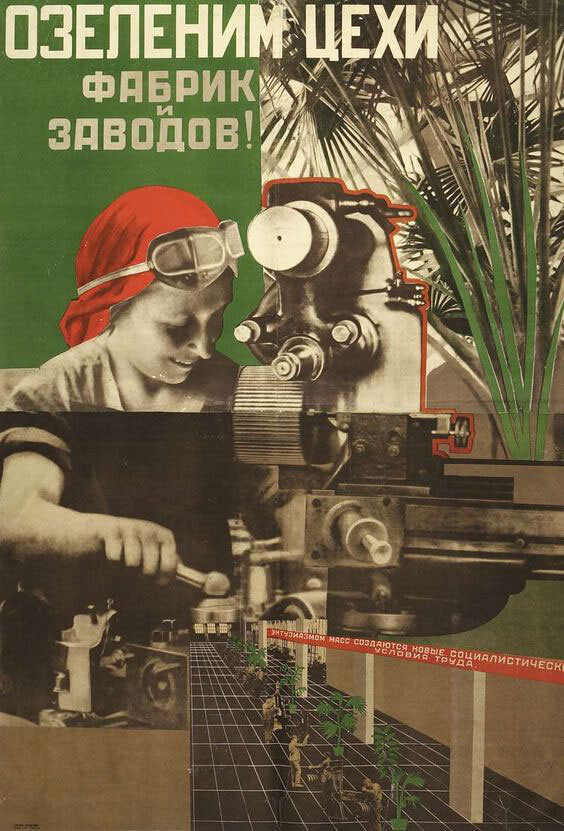

Confined to space, aware of its limits like never before, we are at a global juncture that is determined by a radicalized economy of time. Dilating and contracting through discrete operations of technological systems and communicational networks, spatial experience is either completely dulled (stay-at-home), taken from us (borders closed), or apportioned along a binary spectrum that enacts inherent violence. In Bogotá and Lima, the government determined that “women” may leave their home on even days and “men” on uneven days, legally forcing queer and trans identities to conform in public in order to survive. The reader assembles texts, comics, and soundscapes from the e-flux journal archive to read the individuating intensity of time from a multiplicity of angles.

Infused with an adverbial ideal of acting, feeling, and thinking modeled on the experience of an electric shock, the modern individual who struggles to escape gentrification is indeed no longer moved by what remains the same. They have lost their interest in fixed identities; what does not vary receives scant notice: an indefinitely repeated act, typical of the standardized world of work, seems intolerable to them. The very idea of eternity makes them yawn; marble leaves them cold. Everything that denies life and the musical variations that compose it breeds impatience: perfection and the absolute appear to them like an ontological flaw, an inability to become something else, the result of a serious intensity deficiency. The supreme objects of religious contemplation and wisdom strike them as extraordinarily flimsy. They love music for the changes, with repetition a taste of hell to come. Like Kierkegaard’s hero, they demand the possible or else they suffocate, and not only then; as soon as they are forced to recognize what they know, they gasp for air. What stays the same makes no difference to them. They need either less or more. They would rather change their mind even if the outcome is uncertain than stick to established certainties. Endlessly curious, they are ready to taste pain just as much as pleasure, as long as there is some change and movement, and the sound of being alive—melodious or dissonant—can be heard.

The bonds that new modes of resistance establish with previous historical sequences are scratching loose their very own world-disorganizing potential. Constituent history has never submitted to the tyranny of the textual. The sonic moves audiences-cum-comrades, fleshy things that, in feeling and moving communally, call up the specter of the common project. This is the surplus of their corporeal, anti-transactional transactions. Of their uprising against even minor miseries. Whether one is thinking of music, spoken word, coded patois, scratched records, effective and affective oration, glitching at mechanical interfaces, the multidimensions of performativity in and around sounds—the sonic has always been a most active field in bonds-making. A kind of goddammed Mississippi, seeded with tragedy and resilience, to the frigid Northeast of more buttoned-up organic intellectuals who prefer the tabloid and the blog. Approaching the vicinity of this fact—or perhaps the ways in which its incontrovertibility impinged in our catching-up thinking—led us to commission e-flux journal’s first “text” as track. Of course, “track” seems wanting as a name for the landscape that Lamin Fofana came back with. What we got, what we are still getting, as the thing unspools its textured strands, is our increasingly derelict Now, compressed and distilled, the good shards extracted from it, into a flexible terrain that flickers in and out of different configurations. At one moment, it is riot-space; at another, thinking-space; at yet another, chill-out-and-recharge-space; and at yet another, historical-space. At all times it is a delicate synthesis of multifarious strands and an enterprise in gauging dirt patches in this mad moment, in exposing little bits of hard ground on which our desires for another world, certainly for the end of this one, can continue to find traction.

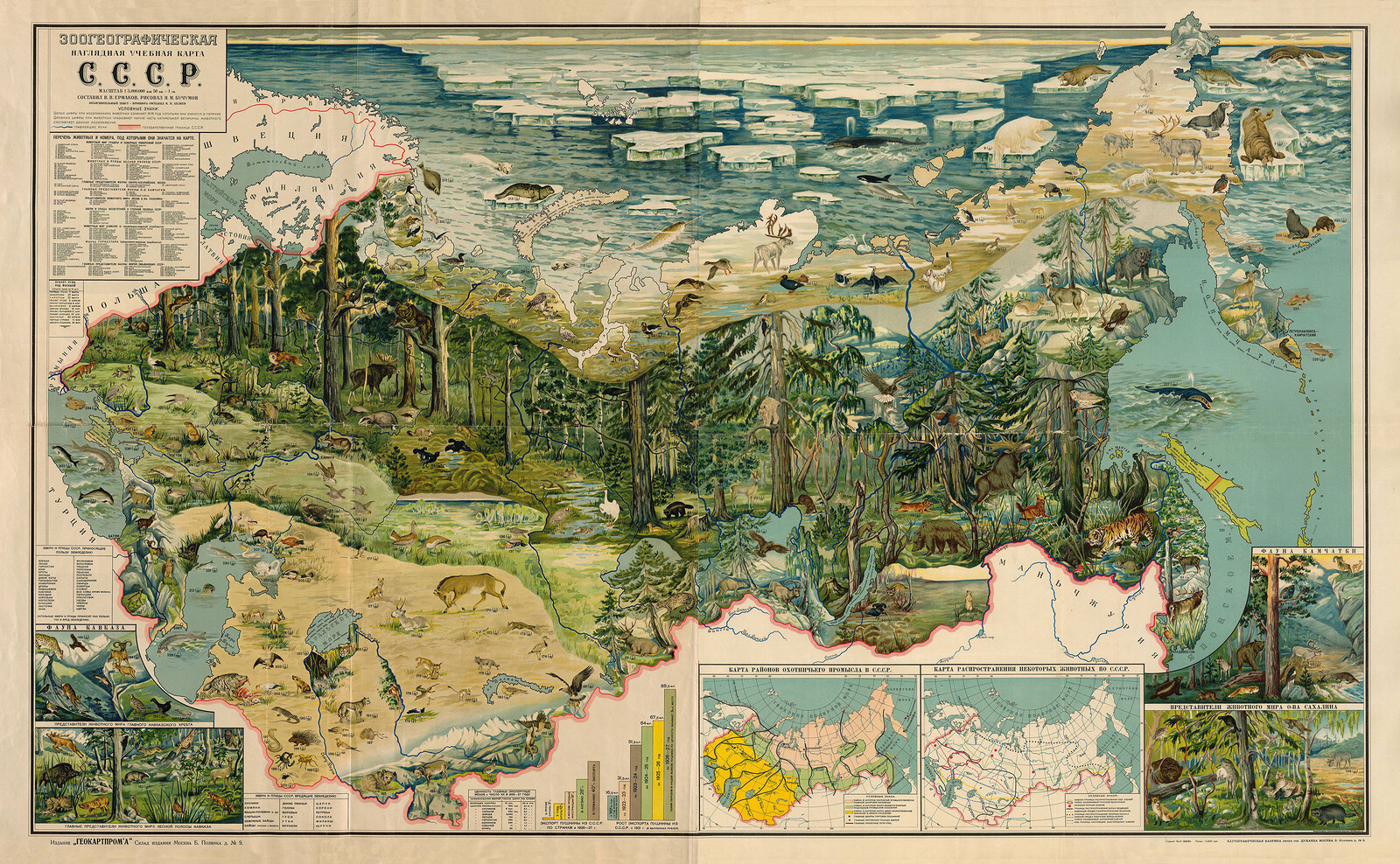

Can we resurrect the people who have not been born yet, but who nevertheless died prematurely due to environmental devastation, hunger, racism, and inequality? Perhaps by learning from Fedorov to think about time as a landscape—one that we shape in the same way that we shape the earth’s surface—we can develop a framework for thinking some of our most urgent crises.