In this symbolic and material economy, black and brown women’s lives are made precarious and vulnerable, but their fabricated superfluity goes hand in hand with their necessary existence and presence. They are allowed into private homes and workplaces. But other members of superfluous communities—such as the families and neighbors of these workers—must stay behind the gates, unless they are willing to risk being killed by state police violence and other forms of the militarization of green and public spaces for the sake of the wealthy. For these workers, the special permit to enter is based both on the need for their work and on their invisibility. Women of color enter the gates of the city, of its controlled buildings, but they must do it as phantoms. Racialized women may circulate in the city, but only as an erased presence.

Work

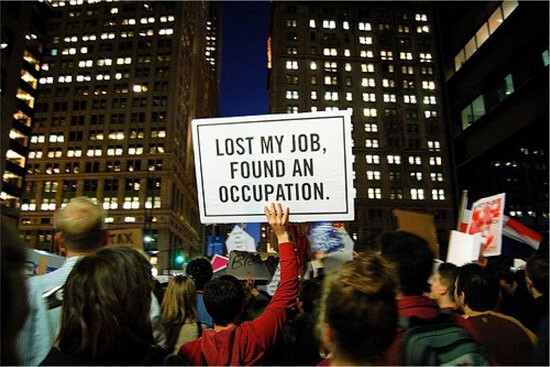

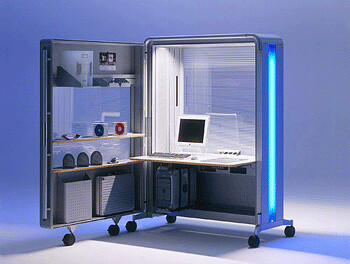

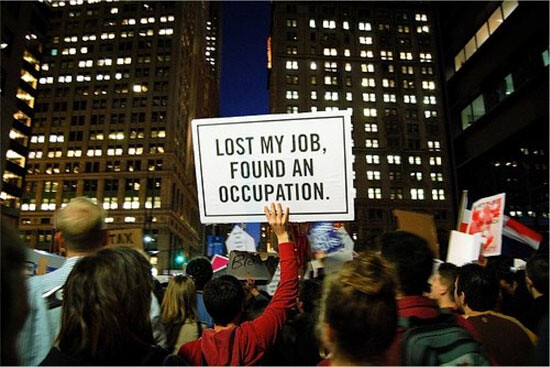

In the first essay of this reader, Françoise Vergès writes of the invisible workers tasked every day with “opening the city.” Now, even as our cities are closed under lockdown, sanitation, transportation, and care workers continue to labor in public, under even more precarious conditions. Food delivery and call center customer service work are both designated “essential,” alongside crucial medical and public safety work, even as the latter structures are privatized and grossly underfunded, paid partially with cheers and claps. The adjudication of essentiality follows mandates to maximally protect economic growth and accumulation, rather than lives. Meanwhile, those who can work from home are obliged to keep production, immaterial or otherwise, on track. Think pieces and corporate memorandums wax normalcy as weekends and holidays blur away due to the destabilization of Post-Fordist time. The legitimizing demands of the work ethic loom large on either side of shuttered doors. Lastly, cultural workers, freelancers, those without contracts, who were already designated flexible, precarious, or expendable, are confined without financial protections or guarantees of medical care or shelter. Taken together, paradigms of labor and parliamentary sovereignty face new legitimacy crises. Simultaneously, an opening has also emerged for some: the possibility for work and projects to become self-determined, to become work that keeps us interested and emerges from our interests. It will take active imagining and collective purposefulness to liberate this autonomously managed work and creation from today’s crisis economics and insert it into new collective horizons. Thus, today’s attempts to organize mutual aid and imagine novel forms of virtual solidarity instigated by physical isolation present a crucial opportunity for studying the contours of being together outside the dimensions of work, at least work that we haven’t chosen ourselves.

The following essays from the e-flux journal archives may be a good place to begin.

Imagine experts in the world of art admitting that the entire project of artistic salvation to which they pledged allegiance is insane and that it could not have existed without exercising various forms of violence, attributing spectacular prices to pieces that should not have been acquired in the first place. Imagine that all those experts recognize that the knowledge and skills to create objects the museum violently rendered rare and valuable are not extinct. For these objects to preserve their market value, those people who inherited the knowledge and skills to continue to create them had to be denied the time and conditions to engage in building their world. Imagine museum directors and chief curators taken by a belated awakening—similar to the one that is sometimes experienced by soldiers—on the meaning of the violence they exercise under the guise of the benign and admitting the extent to which their profession is constitutive of differential violence.