Animism

e-flux presents Animism—a digital exhibition and research project curated by Anselm Franke.

The wonder of being immersed in an exhibition, the social act of public viewing, and the aura of a work of art have never translated easily beyond the physical walls of the museum. During the pandemic, with its long months of social distancing and museum closures, the need for a viable approach to taking the exhibition experience online has grown more urgent in all parts of the world. This need is not new, nor are its challenges, since a small, flat screen, or more “immersive” digital formats, can never fully reproduce the bodily experience of viewing art and exhibitions in real space. And certainly click-through slide shows, Zoom events, or linear video streams are no answer.

Traditionally, however, the way to experience an exhibition beyond its walls or limited timeframe was by way of publishing: the exhibition catalogue. While the catalogue can never reproduce the bodily experience of the exhibition, it never attempts to—on the one hand, it would be ridiculous and a waste of paper, and on the other, the catalogue provides an entirely different view onto an exhibition by including archival, historical, analytical, or literary viewpoints that were never available to the bodily or spatial experience of the exhibition in the first place.

However, many contemporary exhibitions include this documentary approach in the exhibition’s conception from the outset. Most notably, the curator Anselm Franke is known for the “essay exhibition,” which includes documents, artifacts, artworks, and extensive analysis. And we are excited to share with you our first attempt at an online exhibition with Franke’s groundbreaking Animism—a digital project that could also be a cinematic lecture, a speculative text performed by voices, images, and sounds, or a guided tour through an archive with multiple points of entry.

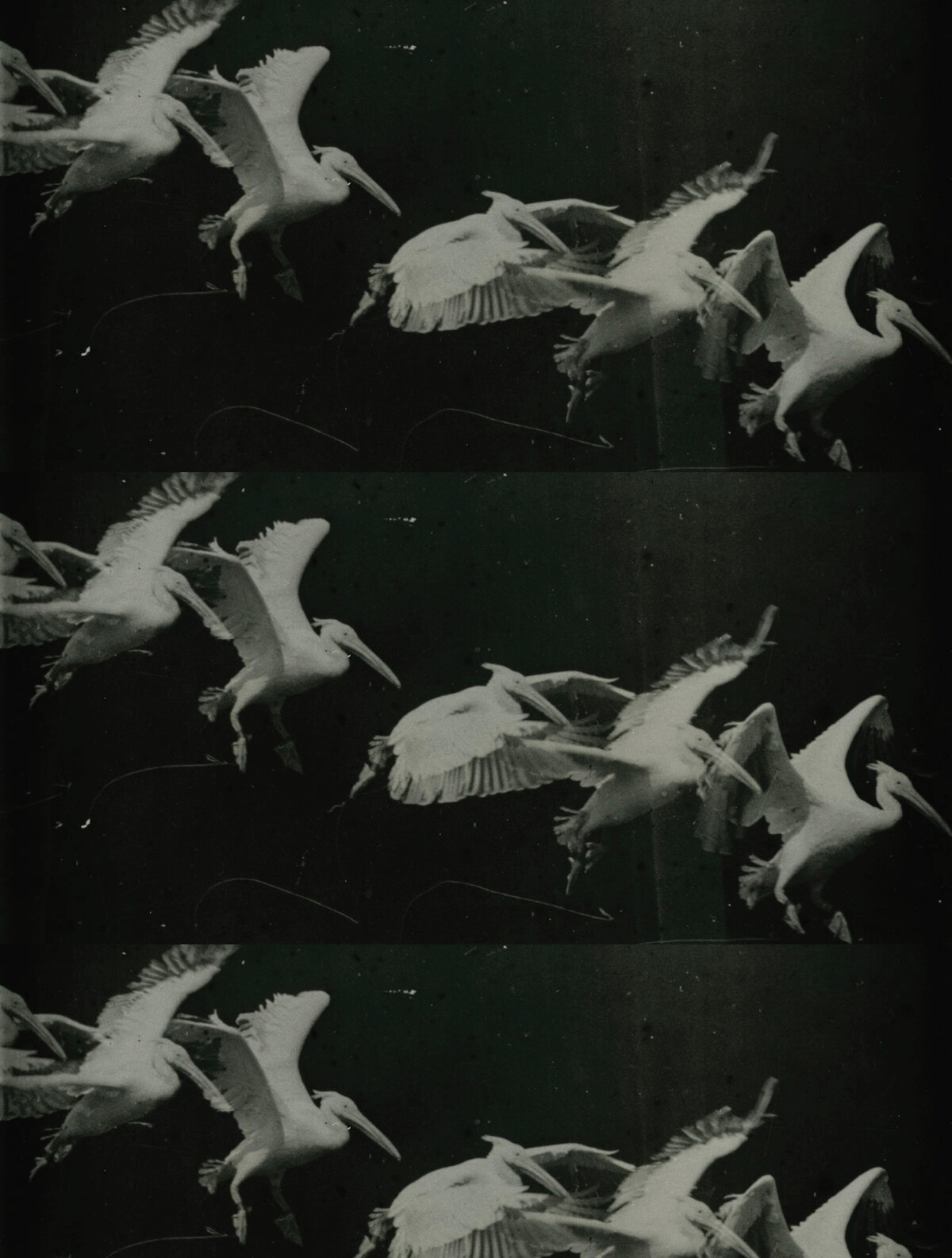

This special digital iteration on e-flux, thematically titled “A Report on Migrating Souls in Museums and Moving Pictures,” features works by Marcel Broodthaers, Walt Disney, Jimmie Durham, Edison Studios, Max Ernst, J.J. Grandville, Candida Höfer, Ken Jacobs, Joachim Koester, Len Lye, Étienne-Jules Marey, Chris Marker and Alain Resnais, Studio OLM, and Natascha Sadr Haghighian.

Taken as a whole, the Animism project tries to envision modern European history returning as its inverse: not as a story of the rise of science or the evolution of secular society and the enlightened subject, but rather as the invention and production of unfree matter and the non-animate—as an imaginary division whose material organization in capitalism is constitutive of modern forms of sociality and power. Animism tries to show that the power of animation cannot be isolated as aesthetic phenomena, since such power concerns the far more encompassing and political question of what it means to be included in a sociality and on what terms. It is not a question of the subjectivity of perception, but of the subjectivity of the so-called object. Decolonizing the term animism means using it as an optical tool that brings into view the boundary-making practices of modern colonial discourse.

Using artworks as guides, this special thematic chapter starts by looking at the divisions and boundaries at work in museums, and moves on to consider what museums do to so-called animist objects, and finally considers animation as an effect of the lifelike in images, particularly in film. The historically saturated sequence of artistic and documentary imagery suggests that modern mass media such as cinema derive their power from the impossibility to contain the collective dimensions of mediation found in the categories of Western psychology.

Animism on e-flux.com is the ninth iteration of the exhibition and overall research project curated by Anselm Franke and previously presented at Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp (M HKA) and Extra City, Antwerp, 2010; Kunsthalle Bern, 2010; Generali Foundation, Vienna, 2011; Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, 2012; e-flux, New York, 2012; OCT Contemporary Art Terminal (OCAT) Shenzhen, 2013; Ilmin Museum of Art, Seoul, 2013; and Ashkal Alwan, Beirut, 2014.

Presented on a specially created platform designed by Other Means and developed by Jules LaPlace, this digital iteration of the Animism exhibition takes the form of a curator’s guided tour of selected highlights from the works, texts, and discourses that have informed or were generated by the project over the course of its many iterations and collaborations. The online exhibition is accompanied by an audio guide produced in collaboration with Nicholas Bussman and is intended to be viewed in a single sitting of around 45 minutes. The exhibition can also be navigated through manually via its featured works and transcript.

Reviews

“Animismus” •

The subtitle of the exhibition – the third in a series of four – gives an idea of the scale of this project initiated by Anselm Franke (and co-curated here in Vienna by Sabine Folie): ‘Modernity through the Looking Glass’ subjects animism to historical analysis, only to discover a chaotic and suppressed counterpart to the rule of pure intellect, as…

The subtitle of the exhibition – the third in a series of four – gives an idea of the scale of this project initiated by Anselm Franke (and co-curated here in Vienna by Sabine Folie): ‘Modernity through the Looking Glass’ subjects animism to historical analysis, only to discover a chaotic and suppressed counterpart to the rule of pure intellect, as the mythological ‘Other’ and ‘vanishing point’ of modern rationalism. The co-curators planned to rehabilitate the concept of animism within this historical treatment, installing it ‘beyond the return of the repressed’ (to cite the title of Franke’s programmatic catalogue essay) and thus beyond the standard modern dichotomies of subject/object, mind/body, conscious/unconscious. Rather than speaking about animism, the aim, as formulated in the essay, was to speak ‘from animism’.

The exhibition offered a captivating, tightly packed survey that seemed to cover every conceivable aspect of the theme: from colonialism and psychoanalysis, via occultism, to the ambivalence towards animism displayed by art (as the only legitimate place of refuge for modernity) and by the museum (as a burial chamber). As a kind of self-reflexive opening statement, the show began with works addressing the ‘mortifying’ effect of exhibition culture: Candida Höfer’s photographic series of ethnological museums (including American Museum of Natural History New York I, 1990 and Ethnologisches Museum Berlin III, 2003) and Jimmie Durham’s pseudo-museum vitrines The Dangers of Petrification (2007), which gives simple stones labels describing them as petrified versions of random objects like a slice of apple or a loaf of bread. Next to these works, Victor Grippo’s Tiempo, 2da. versión (1991) suggested another alternative: Electricity generated with the help of four potatoes runs a digital clock, casting a seemingly inanimate object as an energy source.

This duality between stasis and motion was also exemplified by Luis Jacob’s video Towards a Theory of Impressionist and Expressionist Spectatorship (2002): Jacob asked children dressed in colourful fabrics to pose in front of Henry Moore sculptures, thereby transforming the children into sculptures and bringing the sculptures to life in a single gesture. In Joachim Köster’s My Frontier is an Endless Wall of Points (After the mescaline drawings of Henri Michaux) (2007) – an animation of drawings Henri Michaux made under the influence of mescaline – jagged abstract forms dance across the celluloid. And in Daria Martin’s film Soft Materials (2004) naked humans dance with non-anthropomorphic robots: As they learn from one another, their movements converge.

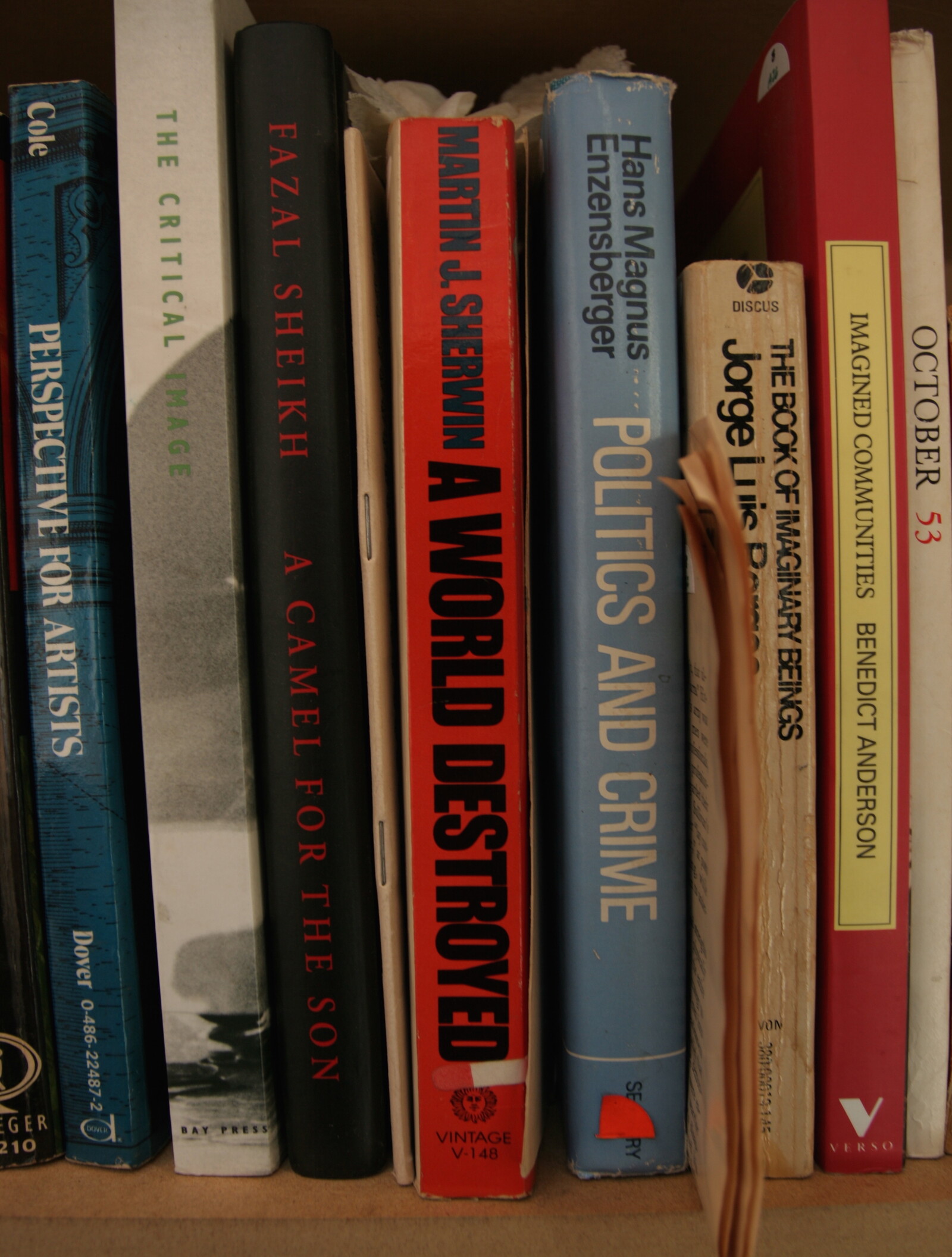

Franke and Folie supplemented the many video works in the show with reference materials: Vitrines featured books and texts such as Sigmund Freud’s Totem and Taboo (1913), Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer’s Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947) or Richard Brautigan’s cybernetic hymn All Watched over by Machines of Loving Grace (1967). Adam Curtis’s four-part BBC documentary ‘The Century of the Self’ (2002) traces the triumphant progress of both psychoanalysis and the Freud family right to the heart of modern PR.

This exhibition worked so well because the curators conceived it as an integrative machine: The selected exhibits fit naturally with each other, and the entire show, with the casual self-reflexivity of projections and vitrines, matched the sophisticated theoretical superstructure in the catalogue. The whole project reflected the increasing entanglement of objects and people, stories and commodities, in world- and époque-spanning networks.

Translated by Nicholas Grindell

“ANIMISM” •

At its core, the exhibition “Animism” is a European export. Now, produced under circumstances of limited financial resources, it has been introduced into China and Asia for the first time. On the surface, German curator Anselm Franke works from aesthetic and anthropological perspectives to raise an anti-modernist proposal for the order of knowledge. From…

At its core, the exhibition “Animism” is a European export. Now, produced under circumstances of limited financial resources, it has been introduced into China and Asia for the first time. On the surface, German curator Anselm Franke works from aesthetic and anthropological perspectives to raise an anti-modernist proposal for the order of knowledge. From participating in “Magiciens de la Terre” in 1989 until today, China’s art practitioners have been disposed to leverage the identity politics of difference in order to establish their position within the globalized art system. Due to recent calls by European scholars to transcend difference and find commonality, this exhibition and the thought system it beholds merit our closer attention.

In “Animism,” the discussion of subject, object, and equality is broadened from traditional humanism and into the realms of psychism, life, inorganic matter, and man-made objects. Evident throughout the exhibition is a basically universalist value system. Examples include the study of minority ethnicities and aboriginal works, such as the film Tusalava (1929) by pioneering avant-garde artist Len Lye, who researched the native tribes of Australia, New Zealand, and Samoa. There are León Ferrari’s collages L’Osservatore Romano (2001-2007); works that use natural objects as medium for mystical experiences, such as Adam Avikainen’s Shenzhen residency project Man go, jack fruit (2013); and works touching upon the relationship between artificially synthesized materials, new technologies, and psychism, such Daria Martin’s film Soft Material (2004), which explores the interaction between a group of robots and two dancers.

Universalism emphasizes transcending national, religious, and individual boundaries to arrive at a universal reality and understanding. In an interview with e-flux journal, Franke cited Stewart Brand’s The Whole Earth Catalog from the 1960s as an example for discussing the close relationship between universalism and artistic practice. Today, Brand is known as an environmentalist who is concerned with ecological degradation and the global problem of urbanization. But back in the 1960s he launched a movement to compel the publication of NASA satellite photographs of the earth, distributing buttons with the slogan, “Why haven’t we seen a photograph of the whole Earth yet?” This slogan and the subsequently released photograph of the earth, known as the “Blue Marble,” were then appropriated as political propaganda. In the image, parts of the globe could not be seen, clearly in reference to the Soviet Union and other Communist countries. In 1947, during the Turkey and Greece crisis, the United States began openly expressing universalism as policy under the guise of the Truman Doctrine, where the goal was to help any country whose freedom was threatened by Russia. This theory became the dominant ideology during the Cold War, replacing the Monroe Doctrine that took geographical boundaries as its organizing principle. The blue earth concept as advocated by Brand, along with the increasingly popular California lifestyle, were used by the American government as anti-Soviet propaganda tools.

After the Cold War, as globalization began to spread in earnest, universalism continued to expand and develop. The return of animism is its latest development: It brings the concept of human equality to include nature, religion, and even inanimate matter, thereby entering a new period. Yet, these strains of universalism and equality are not limited to cultural and ethical demands.

For example, in 2008, Ecuador put into effect a new constitution that incorporated natural resources into the existing legal structure, declaring that rivers, mountains, rocks, and the oceans enjoy the same legal rights as humans. This event became the inspiration for Brazilian architect Paulo Tavares’s film installation, which is also shown during the exhibition. Ecuador’s new constitution is a representative example of an animistic conception of the world. It sounds like something from a happy fairy tale. But, the real world is not a fairy tale. After the constitution went into effect, the Ecuadorean government increased its control of natural resources through large state-owned enterprises, reduced foreign capital, and expanded its control of oil and coal stocks. In terms of economics and politics, Ecuador’s new constitution has strong overtones of nationalism and anti-neoliberal economics. Yet fortunately, in the last five years, Ecuador’s new constitution has had the effect of accelerated economic growth. But for developing countries whose industrial infrastructure is more complete and have yet to find their positions in the globalized economy, such as China, Brazil, and India, this type of rights scheme based on absolute equality can only bring more problems.

More and more people are beginning to recognize that transcending modernity has become an internal drive for Europe. This goal catalyzed the exhibition’s proposals, and determined its pluralist and decentralizing pursuit of broad global connections. Equality is a lubricant and a talisman, at least from a moral perspective. Economically, the supporters of neoliberalism prefer the suggestion and establishment of a homogenous, flattened international market. But the issue remains that equality has not eliminated the hierarchical order of production; politically, the differences created by identity politics will not disappear in any short amount of time. As a result, talk about equality outside of the context of society and economics lacks practicability. The reality is that today’s capitalist economy remains one of oppression.

We can say that as a suggestion for crisis ethics, the significance of “Animism” lies in providing those of us who work within a different system a position of reference. Culturally, we are always wavering between extremes of pride and inferiority, unable to find a balance; we excel at showing off, but lack the volition for reflection. At the same time, the various European responses to crisis do not signal that they face imminent collapse; this is just a part of their tradition. Since the early days of modernism, Europe has continuously faced all manner of crisis. This sense of imminent crisis and ensuing anxiety benefitted from modernist thinking, that generative mechanism of resistance and reflection. Viewed from this perspective, “Animism” is a quintessential product of this system.

“An “Undisciplined” Form of Knowledge: Anselm Franke”

Anselm Franke has become known for developing curatorial projects of great scope and influence, which are characterized by solid and extensive long-term research processes. In their practice, theoretical and discursive aspects play a fundamental role, and a dialogue between research and art practices has a critical impact on contemporary world essential…

Anselm Franke has become known for developing curatorial projects of great scope and influence, which are characterized by solid and extensive long-term research processes. In their practice, theoretical and discursive aspects play a fundamental role, and a dialogue between research and art practices has a critical impact on contemporary world essential issues. The conversation with the German curator flows through some of his past and ongoing projects, on matters such as: the need for negotiation among different ontologies, the possibility of acting on the dichotomies of modernity to complicate them, the contradictory place of the exhibition as an unveiling of gaze (in order to understand the complexity and the weight of colonial past), or embracing the irrational, the mimetic, or the animic to propose another social order. From his words, we can grasp the need to produce an “undisciplined” and unsettling form of knowledge that calls into question reality and its perception again and again, until you can reinvent the way to bring the most urgent subjects into existence.

Juan Canela: Anselm, I think we could agree that we live in a time in which the social accord between individuals, society, and state has been broken, and it seems urgent to rethink this issue from different perspectives. Precisely Nervous Systems, one of your latest projects presented last year at the HKW in Berlin, focuses on how our experience and understanding of the “I” and the “social” is changing and questions how the large amount of data on human behavior affects and transforms such behavior. What is your perception on this panorama, and how do you articulate the idea of the nervous system to rethink the relationship between life and technology, between the organic and the material?

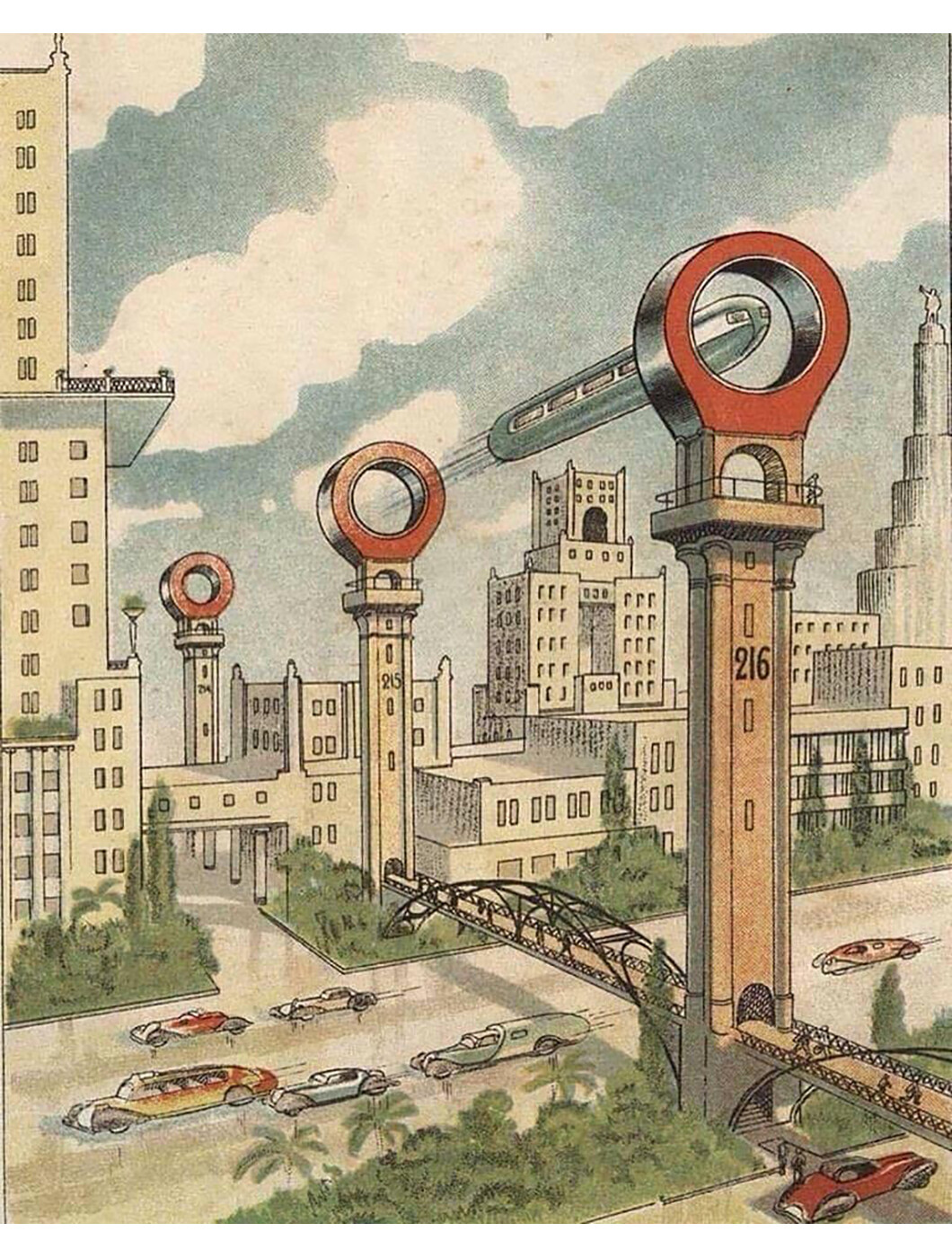

Anselm Franke : It gradually becomes clear that the digital economy has far reaching effects on our social behavior. Indeed our very sociality, that is, our “being-in-relation,” has become a resource for a new form of extractive economy. Everything we previously might have deemed personal has been subjected to profiling and pattern analysis, and our very feedback mechanism with the world and others are hence changing. In the Nervous Systems exhibition, we traced how the concept of the nervous system has been used as a metaphor since the dawn of the industrial age—and particularly since the rise of cybernetics and information science—to advance the idea that computers and biological organisms are compatible and can and need to be integrated.

Already in the 19th century, the nervous system was both subject of scientific inquiry and a widely used metaphor in relation to electrification and the shock of industrial modernity. However, it was in the 1940s that the organic nervous system—with its firing synapses—has been equated with a switchboard, with so-called “logical gates,” with the binary operation on which our digital age is built. We wanted to highlight the ideological character of this equation, but also its lure. After all, there is more than an Orwellian side to cybernetics; it also paved the way for a veritable revolution in Western metaphysics, and it breaks through ontological division, and raises the question of “ecology.” I think right now public opinion still seems very divided over whether we are about to enter digital utopia, or reach the technological singularity, or whether this idea of letting “smart” networks take over the management and governance of our polities might not ultimately turn into a social nightmare and espouse a neo-reactionary politics such as Peter Thiel’s.

In the exhibition, we also highlighted how the emerging data-positivism, and the dream of a new “social physics,” ultimately must fail to grasp the dynamics of social processes. Overall, I think we painted a rather grim picture of how our technologically integrated societies have developed under the conditions of platform capitalism. But we insisted that it’s not about critiquing technology as such, but the ends it is serving. What we are witnessing is less the disruptive innovation that is propagated by Silicon Valley, but a freezing of reality into reductive categories and the re-inscription of those social categories through pattern analysis and algorithmic modeling. We wanted to create awareness, encourage dissociation, and instigate social invention in response.

JC: As in your other projects, Nervous Systems brings materials that come from different fields of knowledge, produced by artists, technologists, theorists, or activists. How does this gathering of different knowledge work, and what is the importance of trans-disciplinary in your curatorial practice?

AF: This was a thematic exhibition, a so-called “essay exhibition.” Such an exhibition performs a simple, necessary gesture with regards to art and other exhibits: It amplifies the oscillation between meaning and material, rather than short-circuiting them, as most thematic exhibitions do. Working with art, text, and other artifacts, the essay exhibition seeks to induce a definitional crisis with regards to the “topic” of the exhibition, the subject matter, the objects. The indeterminacy of art, the generality with which it performs its “political” gestures, seems to me to have exhausted itself. So, if art’s critical function is to throw us back onto our tacit assumptions, our worldviews, and to instigate a process of reflection in a zone of non-identity, then it has become important to explicate these assumptions historically and ideologically, and to test the generality of art’s political gestures against history’s particularity. It is not about using art to illustrate a theme, as is often assumed, but the opposite: to challenge discourse with art and art with discourse, in order to make this oscillation between meaning and material productive. This allows for a precise, new kind of conversation; an “undisciplined” and unsettling form of knowledge then sometimes comes to the fore, which puts reality and its perception into question again and again.

JC: In recent years, you have developed curatorial projects that are characterized by solid and extensive long-term research processes. Projects such as Animism (2010-14), The Anthropocene Project (2013-2014), The Whole Earth (2013) or After Year Zero (2013), besides taking the pulse on essential contemporary culture topics, establish working processes and public and exhibition moments in which the theoretical and the discursive have a primordial role. How do you come across with the subjects you work with, and what is the relationship between the research stage and the audience, between the theoretical and the artistic production?

AF: There is always a group of people, typically artists and writers, with whom I think. I am almost never alone in any of these projects, and most of them are developed in response to both a particular work—or a body of work—and a series of books. Animism answered to the work of Jimmie Durham and the early Walt Disney, for instance, and the books of Michael Taussig and Avery Gordon. Each project develops out of the other, and they are each directed against the currency that certain received ideas have in contemporary discourse, including cultural production and “interested” art. The topics of these projects are often initially hidden in works of art, as an implicit backdrop. I read art discursively and discourse aesthetically, perhaps. I then try to render these “conditionings” explicit, and create discursive contexts that allow for certain shifts in the field, allowing for new alliances across different registers of language. It is, in each instance, an attempt to step out of certain frames, certain narratives, and certain limits of the cultural imaginary. Stepping out of these frames is both a critical effort and an aesthetic effect, a modern effect. I don’t see them as separate and refuse to succumb to the mystifications that are currently defining the image of contemporary art. I also aim at articulating knowledge as precarious, to make clear what it is that is under threat at a given time. Animism, for instance, was also about the intuition that film did not just restore gesture and older forms of mimesis to modern human beings, as Walter Benjamin diagnosed. It was also about the fact that since digital animation the situation might have been inverted, from an opening to a closure. People no longer go to the cinema to learn to cry again, but instead are trained to accept that even their emotions might not be theirs anymore.

JC: I remember visiting the Ape Culture exhibition (2015) where the spatial differentiation between the research section—arranged in cross-panels almost like pages of a book—and the exhibition part surprised me. But in other projects, the research was much more integrated in the exhibition. This relationship is always complex, and even more when the theoretical has as much weight as in your projects. How do you decide the articulation of that dialogue in each case?

AF: Yes, the initial idea here was to keep the “art” and the “science” apart, the symbolic and metaphoric uses of apes and monkeys on the one side, and primatology and its political, cultural, and legal contexts on the other. Looking back, I do think this distinction between the research and the art was not completely resolved. We did not want the artworks to be “about” apes: This part of the exhibition should speak of the mimetic powers that the slippage of signification releases. Apes, as simian mirror, destabilize signification. This slippage is political, but also inherently aesthetic; it inhabits the borders of linguistic communication, but it also opens up a realm of meta-communication about the means of communication, of interacting bodies and their affects. Several films were shown to further activate this exploration of mimetic behavior, mirror-effects, and desires in a reflexive way: We cannot escape our own ape-hood. While each individual artwork was powerful, they nevertheless ended up perhaps looking a bit too much like a more conventional collection of works on the “topic” of apes. We think that this part of the exhibition should have been even further removed iconographically, and turned more into a meta-reflection on different registers of mimesis and social power.

JC: You might say that a path can be drawn through your practice surrounding topics related with how we understand ourselves in the world, and how we organize as a society in relation to it. In Animism, you point out the battlefield that is established on the border of colonial modernity, which concerns the urgent question of the transformation and negotiation of different ontologies. You raise the question, in my opinion really necessarily, of understanding whether we are able to leave the matrix of modern dichotomies, not by abandoning them, but by recovering our capacity to act on them. Could you comment a little on how this project was developed, and how you work on a subject like this in the exhibition format?

AF: It is a question of the vantage point: From where do you ask the question? What are the underlying assumptions? What have they to do with the way an object and the perception and knowledge thereof is constituted? When you assume, for example, that ultimately the physical world is devoid of animation (a widespread attitude in the mechanistic worldview of the 19th century, during which the concept of animism was coined), and that the psyche is a phenomena that pertains only to the human inner life with no “objective” material reality (other than perhaps the nervous system), then your explanations of so-called animistic phenomena will always predictably follow a pattern yielding the same kind of contradictions, based on and always returning to non-animistic assumptions. The perception of “spirits,” for instance, is explained as a projection or even approximated to a psychological disorder, and thus ultimately, they will be explained away. “We” can acknowledge animistic phenomena only in the registers of fiction, but non-modern people “mistake” this fiction for reality, etc. “They” are not able to make the “correct” rational distinctions, the correct border between the subjective and the objective. But that border is ultimately a historical variable. And this is in itself a colonial mechanism of grave consequence; it amounts to an ontological death sentence—that historically helped to justify imperial conquest, even genocide—and continues in the rationale of capitalist modernization in various forms.

So in making this exhibition, I wanted to create an experience of this border itself, and its malleability. And I wanted to show how the exhibition and the museum is itself implicated in the making of this modern system of ontological and disciplinary divisions. The starting point of the project was thus to invert the usual line of argument: Not to explain the effect of animation across the animate/non-animate divide—whether in the fictional registers of art or the non-fictional registers of cultural practice—but to seek to interrogate the making of the division, of different kinds of divisions that ultimately condition our perception and cognition of the world. The initial hypothesis was that “animism” is not a curious, exceptional belief system held by certain people. Rather, it is an irreducible phenomena of our mediality, our being-in-a-medium-of-communication. We will never escape being animists, but our animism can be organized in manifold ways.

The project thus attempted to provide both a critical viewpoint on modern boundary-making techniques and their naturalization in the form of disciplined knowledge and institutions. And it wanted to also transmit a sense of openness, of the possibility and reality of otherness. Last but not least: The key problems of modernity, which I believe are questions of mediality and of “framing” in relation to the constitution of sociality, are ultimately exposed in the encounter with other ontologies. How does one unframe one’s gaze? The question of “framing” is not only an aesthetic question; it is a question of the social order, the making of the socius, and of ontology. And this perspective needs a dialectical, stereoscopic gaze on the past, which can be activated, perhaps paradoxically, in the medium of the exhibition.

JC: Overcoming these modern dualities is something that also appears in The Anthropocene Project, diluting the relationship between humanity and nature and questioning what processes we can follow to change our future prospects; or in The Whole Earth, reflecting on how to find a narrative that explains the reconciliation of binaries, the confluence of opposites, embracing what was previously excluded from the constitution of the modern social and epistemological order: the irrational, the mimetic or the animistic. How do you picture the current moment in relation to these questions? What do you think we can bring from contemporary art to these processes?

AF: Contemporary art can traverse the horizon of any given cultural imaginary, and also delineate and expose its limits. That’s what we attempted to do with the art, the films, and the music that was presented in the context of many other documents in the Whole Earth exhibition, but here we dealt with the limits of the seemingly limitless, the unbounded planetary interior! The Whole Earth was the first exhibition project we did at the HKW in Berlin under the framework of the multi-year project on the Anthropocene in 2013/14. It was crucial in my eyes to provide first a historical backdrop to the “planetary” discourse of the Anthropocene: Indeed, the major lines of argument of the Anthropocene discussion had already been invoked some thirty years ago in the wider context of the Whole Earth Catalogue in California, in the milieu of the counter-culture, experimental cybernetics, environmentalism, and many of the Earth Systems scientists who are now trying to carry this discourse into politics—who in fact had also some roots in this milieu, and indeed were early on first popularized in the Whole Earth publications such as the CoEvolutionary Quarterly, already in the 1970s.

Yet our exhibition also was meant as a reminder that this appeal to a planetary dimension cannot be politicized effectively without political analysis of capitalist and colonial relations. We felt it was important to recount the story of the imperial frontiers and especially how the Whole Earth milieu also gave rise to the Californian ideology of the 1990s. The “whole systems” approach transformed into the market ideology of the New Economy. In the same manner, the Anthropocene discourse could relatively easily be appropriated—it would not be surprising if Siemens would pursue their political lobbying, for instance for their “green city” solutions that actually disguise the privatization of the commons on a massive scale, under such a banner, would it? The ideology at work in the Californian articulation of universalism and in cybernetic ideas of management have largely failed us. And yet, many of the ideas at work there could, and also have occasionally been put to a different use.

How do I picture the current moment? I think it is crucial to realize that the return of “the irrational, the mimetic, or the animistic” that you mention, this drive to redeem the divisions of modernity during the time of the counterculture, did not bring about the desired reconciliation: neither with “nature”, nor with the suppressed, nor those excluded from the benefits of capitalist economies. It was in that sense an anti-politics. It ended up as the neoliberal ideological interpellation of the subject to reconcile and de-alienate oneself. On a more abstract scale, this is connected with the hypothesis presented by Erich Hörl in the context of the project, namely that “ecology” might well have been a discourse less about anything “natural”, than technological. Ecology, he says, exposes the original technicity of sense. It is a discourse that is enabled by—and needs to try to come to terms with—the becoming environmental of technology on a global scale, the rise of the so-called technosphere.

In terms of the broader picture, I think that we are currently facing the monster of extractivism and the profit machine with new force, combined with the return of the unredeemed evils of the colonial past. We have to rework the answers of the past, but also acknowledge the continuities of struggles, and that means to acknowledge and defend complexity. We need new narratives, which are outlining how we got where we are today, and provide new ways of making sense of our situation. But it is not the narratives themselves that need to be new; the “tradition of the oppressed” knows them all throughout. It is how they address themselves—and how they bring a subject into being—that needs to be reinvented.

JC: Thinking of the evils of the colonial past, you have opened 2 or 3 Tigers, the current project at HKW dealing with the transitory zone occupied by the figure of the tiger separating civilization from wilderness, the living from the ancestor-spirit world. You are trying here to rework the answers of the past, questioning the historical nature of mediation. Could you tell us a little about how you, together with Hyunjin Kim, articulate this project?

AF: This is an exhibition that developed out of several projects I was invited to curate in East Asia in the past 4 years—two iterations of the Animism exhibition in Seoul and Shenzhen (the former upon invitation of Hyunjin Kim), but also the Taipei Biennale 2012, the Shanghai Biennale 2014, and the opening exhibition of Gwangju’s new Asia Culture Complex. In each of these projects, I tried to draw on the perspective developed with the Animism exhibition, in order to activate a different imaginary of the history of modernity in East Asia, one that resists identitarian divides, imperial and nationalistic schemes, and the still escalating effects of Cold War militarization.

With 2 or 3 Tigers, we tried to bring together works that re-articulate the question of “tradition” in relation to—and as part of—modernization ideologies, a topic that Hyunjin had also previously tackled in her work in Korea. Each of the works interrogates history and tradition but from a non-essentialist perspective. The exhibition is different from most of the other projects discussed above, in the sense that it does not include any documentary material in addition to the works of art. These works themselves are mostly epic in their range of historical narratives. The starting point is the opulent work of Ho Tzu Nyen, a new and final piece of a series of works he did on the role of tigers in Singaporean and Malayan history. In the overall conceptual narrative, tigers (and “weretiger” mythologies in particular) are foregrounded as “liminal” figures through which different ways of organizing human society in relation to its boundaries and protocols of mediation can be discussed.

Because the tiger is a figure that crosses the partitions of the modern world on a subterranean level, antecedent to the divisions, but upon surfacing as a symbol or image, it mediates them, as if from the other side. Thus, for instance, the tiger morphs historically from a mythical creature that marks, from its outside, the limits of the society of humans into a symbol of national identity and military prowess, as when it is charged with crafting a continuous national space and body politic—zoomorphically mapped, for instance, onto what is today the divided Korean peninsula—to re-emerge in the more recent metaphor of the Tiger States, symbolizing the hypermodernizing condition of recent decades. The mythical symbol of the tiger is often put in the service of reifying national identities, but in this project, it is torn away from these molds and used instead for a different imaginary: that of a history of experience that transcends the divisions inflicted by colonial history, subsequent militarism, and national conflict. It is a medium that might hence help to imagine identities that are not based on these divisions and their paranoid psychology.

“Animism” •

Curated by Anselm Franke, the touring exhibition Animism makes its Asian debut in OCT Contemporary Art Terminal (OCAT), Shenzhen . The layout of works in OCAT’s 1,000sqm oblong hall is well proportioned: the big screens hanging from the ceiling for film and video projections create an archaeological field of moving pictures, while rows…

Curated by Anselm Franke, the touring exhibition Animism makes its Asian debut in OCT Contemporary Art Terminal (OCAT), Shenzhen. The layout of works in OCAT’s 1,000sqm oblong hall is well proportioned: the big screens hanging from the ceiling for film and video projections create an archaeological field of moving pictures, while rows of display cases beneath them offer a close look at smaller drawings, videos and photographs displayed in an archival style.

There is no given visiting route; visitors must find their own path when it comes to constructing relevance among the works. This is a challenge, but a respectful one: without a simple explanation or singular narrative, everyone has to develop his or her own logic, based on the evidence of the exhibited material.

Originally deployed by nineteenth-century anthropologists, the word ‘animism’ at first referred to a certain kind of worldview in which subject and object are not divided according to the modern Western view. But the show has no intention of calling back the spirit of the premodern age.

It brings together works including historical documents (eg, Animal Magnetism, an illustration from the eighteenth century), films (Chris Marker and Alain Resnais’s Les Statues Meurent Aussi, 1953), archival displays (the second card of the Rorschach inkblot test, 1921) and contemporary art, to open up powerful discourse arising from a series of dualisms: modernity and premodernity, urban and natural, rationalism and barbarism, European and the other (alien).

Walt Disney’s short The Skeleton Dance (1929) offers a good starting point from which to explore the show, in part for its highlighting of the idea that pictures can be ‘animated’. Some works about consumerism propose the question of how the objectified subject yearns to become an object – a reversal of projecting subject upon object (the projection theory to interpret ‘animism’).

If we do not immerse ourselves too deeply in one work, but go through the works around the exhibition hall, we would be able to picture clearly how the establishment of the modern order takes place alongside the process by which the irrational, alien and primitive cultures were defined as ‘the others’. Angela Melitopoulos and Maurizio Lazzarato’s ongoing project on Félix Guattari (three-channel video installation Assemblages, 2010–) and Paulo Tavares’s Non-Human Rights (2011–12) explore how such ideas regained currency as ‘critical weapons’ against modernity in the postmodern era.

To emphasise the fact that the real target of his project is modernity, Franke once wrote the following (haunted by the spectre of Marx): ‘A ghost is haunting modernity – the ghost of animism.’ If ‘ghost’ as a nonphysical being is something that appears in unexpected places at unexpected moments, the same expression could also be used for the hidden subject of the animation project: colonialism.

We are haunted by the ghost of colonialism as well. Animism as an exhibition does not simply rethink colonialism at the political, economic and psychological level, but also questions the colonialism that appears anywhere, at any time, in human thought and knowledge systems. According to recent critiques of modernity, everyone is colonised by modern concepts, even those who play the role of the colonist.

That’s why I was haunted by the suspicion that by touring around the world, the show itself is practising a kind of intervention. It is one at an atomic scale, going into the mind of every audience member – no matter whether or not they aspire to such an intervention.