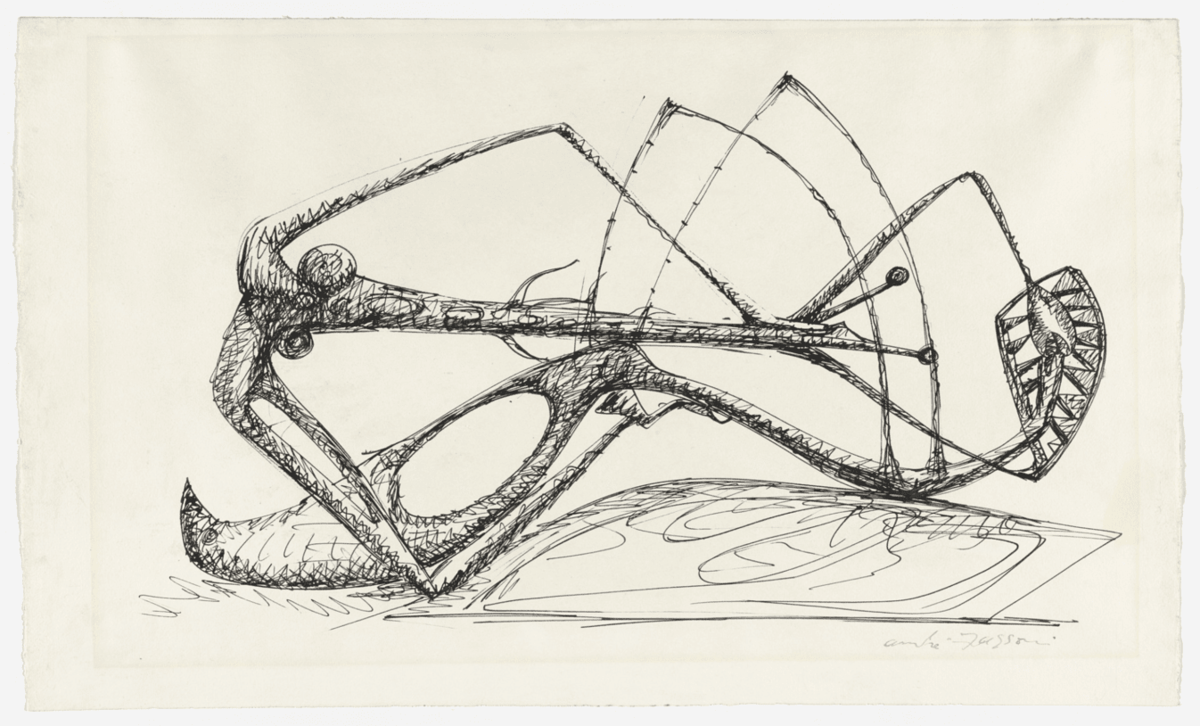

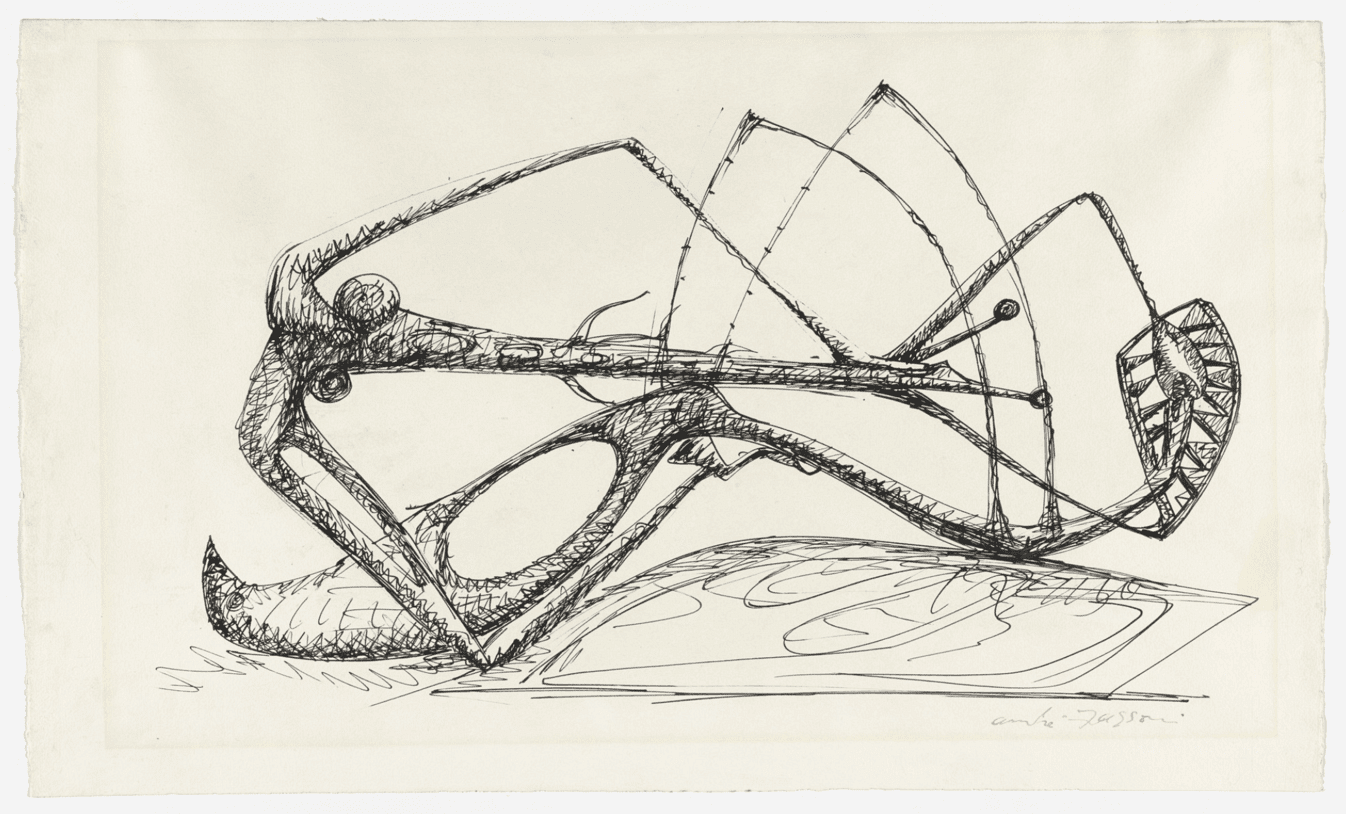

André Masson, Praying Mantis, c. 1942

At least since Sartre’s Being and Nothingness, we have tended to think that the gaze of the other—especially the gaze of the powerful other—“objectifies” us. Thus we are called to reclaim our agency, our identity—with the goal of resisting this objectification. But is the phenomenological analysis that underlies the concept of “objectification” a correct one? Is it really the case that we are recognized by others as mere things among other things? Yes, maybe humans are things, indeed—but different from other things.

Let us take an example. I am walking alone down an abandoned street at night. I see buildings on the left and right, stones, clouds, and maybe the moon. I am quiet and relaxed. But then I see a human figure coming toward me from the other end of the street. And immediately my mood changes. I feel tension, I am ready to avoid or repel a possible attack. So, yes, humans are things—but they are suspicious things. They are unreliable and potentially dangerous things. We don’t know what to expect from them. We know what to expect from a stone and even an animal, but we don’t know what to expect from a human being. Maybe a polite greeting, maybe a bullet. There is something in humans that makes them suspicious. Let us call this something spirit.

The notion of spirit is overloaded by metaphysical traditions and connotations. Instead, let’s turn to fairy tales and science fiction. What does it mean to say that a house is haunted by spirits? It means that the house has become unpredictable. It has lost its stability, reliability—it has lost its identity. Something happened to it that made it dangerous and destructive. And this something cannot be fully scientifically examined, understood, or controlled. Haunting spirits are trickster spirits. From time to time they inhabit precious stones, cars, or computers, but they also inhabit human beings. Humans are spiritual, unreliable, treacherous things. That is why the main goal of power has always been to discipline humans—to make them reliable and predictable. In other words: to make humans things like all other things.

To discipline the spirit, global bureaucracy uses the body and its needs and desires. Indeed, one has to eat and drink, one has sexual desires, one wants to avoid pain and death. These needs, desires, and fears put a limit on human unreliability and make humans governable. Of course, when this bureaucracy practices its disciplinary work, it tends to argue in terms of ethics and law. Revealing this official ethical order as essentially hypocritical was the main achievement of the literature and art of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Bureaucratic control and administration operate not by juridical and ethical but economic means. Insofar as humans have to eat, drink, and have sex, they find themselves caught in a net of economic dependencies. Modern and contemporary slavery is economic slavery. Nietzsche famously believed that to escape this economic slavery, people would have to radicalize their desires in a way that these “uneconomic” desires could carry them beyond the borders of the existing—and potentially any possibly existing—economy. An aristocratic, aggressive will to power and pleasure does not accept any economic limitations. Bataille and Deleuze continued in the same manner: vital energy and desire are excessive, potentially infinite, and one should not frustrate them by accepting the small happiness of the “last men.”

However, is vital force the truth of humanity? In fact, this sounds implausible. A finite human being cannot be a vehicle of infinite desire. From time to time, one would like to switch off one’s desiring machine not because one is suppressed by the state apparatus but simply because one is exhausted, feels sick, or needs some rest—needs to take a break from circulating in the rhizome and simply read a book, sit in a chair, or lie in bed. After all, our culture channels our desires in ways that are tiresome and boring: rock concerts, noisy bars, dirty streets, formulaic movies about vampires and zombies. The popularity of vitalist thinking has to do with the naive belief that, unlike spirit and reason, vital forces cannot be hypocritical. However, the example of Nietzsche demonstrates the opposite: one can pretend to be vital and aggressive when one is weak and vulnerable. And also Bataille: this prophet of blood and dirt, explosivity and spontaneity, spent his days working as a librarian in the French National Library. In his brilliant book Medusa and Co., Roger Caillois describes the tricks that insects use to appear bigger and more dangerous than they are. It is obvious that Caillois is describing his surrealist friends, who used their art to seem like vital, aggressive, and dangerous beasts when they were, in reality, timid Parisian intellectuals and poets. Caillois writes about two types of mimicry: to become like everybody else, but also to become exceptional and “alternative.” We can say that Nietzsche and Bataille invented a new type of hypocrisy—vitalist hypocrisy. The subject of this vitalist hypocrisy pretends to be carried away by vital energies towards impossible ecstasies but at the same time cares about their workplace, their home life, and their mortgage.

In order to find an alternative to economic slavery and exploitation, we should turn instead to the good old tradition of contemplation. In the era when modernity was ascendent, the contemplative attitude, vita contemplativa, was radically rejected. Only vita activa remained—political activity and work that served the success of the individual and society as a whole. The main imperative for humans became: be useful! Contemplation was rejected because it was accused of being a useless waste of time. In reality it was suppressed because it was dangerous to bureaucracy. The subjects of contemplation are ascetic. They supress the “natural” needs, desires, and fears by which power manipulates humans—and this makes them unreliable, ungovernable, and spiritual. Contemplation is the manifestation of a different, “unnatural,” metaeconomic desire—the desire to escape the body and all its needs and desires. It would be too easy to say that this different desire is unrealizable and, thus, should be abandoned. Indeed, we have already learned that desire cannot be abandoned but only suppressed. That is also true for metaeconomic desire—the desire for liberation from economic slavery. This liberation is the actual goal of all forms of ascesis: by imposing self-chosen limits on bodily needs and desires, the subjects of contemplation liberate themselves from economic servitude—at least partially.

Even if, in the era of modernity, the contemplative attitude was suppressed, it was not completely lost. Avant-garde art emerged in the place of contemplation. Avant-garde artists subjected the artistic tradition to reduction, simplification, and minimalization. They followed rules and a discipline that they imposed on themselves. In this sense, the art of the avant-garde was ascetic. It avoided being pleasant and seductive. It did not want to be liked—but only appreciated. In this sense the avant-garde was also anti-commercial, anti-economic. It was the expression of a desire to escape economic dependencies that stemmed from the dependence of artists on their public. The public was not considered as a mass of people expected to like and buy a certain artwork, or to reject it. The proper reaction of the public to avant-garde art is not to like it but, rather, to join it. In this respect the avant-garde is similar to the spiritual practices of the past: you could join them or ignore them, but it made no sense to like or dislike them.

In the era of modernity it was often said that the traditional posture of contemplation was only a trick that guaranteed its subject a certain degree of social recognition plus a corresponding degree of consumption. After all, contemplative spirits also have to eat and drink to remain alive. Accordingly, the contemplative attitude was often considered to be parasitic, reflecting the mentality of the upper class, which was exempt from physical work. It was also said of avant-garde artists that, ultimately, they had to sell their artworks to survive. And it was again said that these artworks reflected the mentality of the upper class—the members of which enjoyed the useless and the dysfunctional as proof that they can allow themselves to do so. It is, of course, true that such great contemplators such as Socrates and the Buddha were recognized by the cultures in which they lived—at least after their deaths. And it is true that many avant-garde artists were recognized and are still remembered. But are they remembered because they exemplified the lifestyle of the upper classes? Of course not. These classes practiced and still practice pleasure and consumption—and in this way make their contribution to the economy.

We remember these contemplators and artists like we remember floods or volcanic eruptions—but also revolutions and wars. Our memory is structured in such a way that it archives all the manifestations of danger that have a potential to destroy our lives. Of course, the trickster spirits that erupt in these contemplators and artists cannot destroy our bodies by direct violence—so, indeed, at first glance they seem to be peaceful and innocuous. However, there is always the danger that society will join their ascetic lifestyle and thus undermine and ultimately destroy the basis of economic life—leaving us without the means of existence. In The Accursed Share, Bataille describes Tibetan lama society as just this kind of decadent society destroyed by the mass spread of the desire for contemplation. In fact, critics of avant-garde art also saw in it the signs of a coming decadence that could potentially destroy Western civilization. The fear that metaeconomic desire will inspire the masses and destroy the economy determines the narratives of modern historiography. In our current civilization, metaeconomic desire is described and explained as an effect of different kinds of “trauma.” It seems almost self-evident that a normal, healthy individual would never “punish” themself by ascetic practices. Instead, such an individual is supposed to desire and enjoy the pleasures of life, understood as corporeal pleasures. Thus, we believe that only traumas—especially childhood traumas—can produce in humans a desire to escape from the necessities and seductions of life. Accordingly, stories about the ascetic lives of philosophers and artists are built around their alleged traumas and are used as cautionary tales, with the goal of frightening new generations and directing them toward productive and economically useful work that allows them to “enjoy their life.” However, every cautionary tale can be read as a source of not fear but, on the contrary, inspiration—and such readings happen, indeed, time and again.