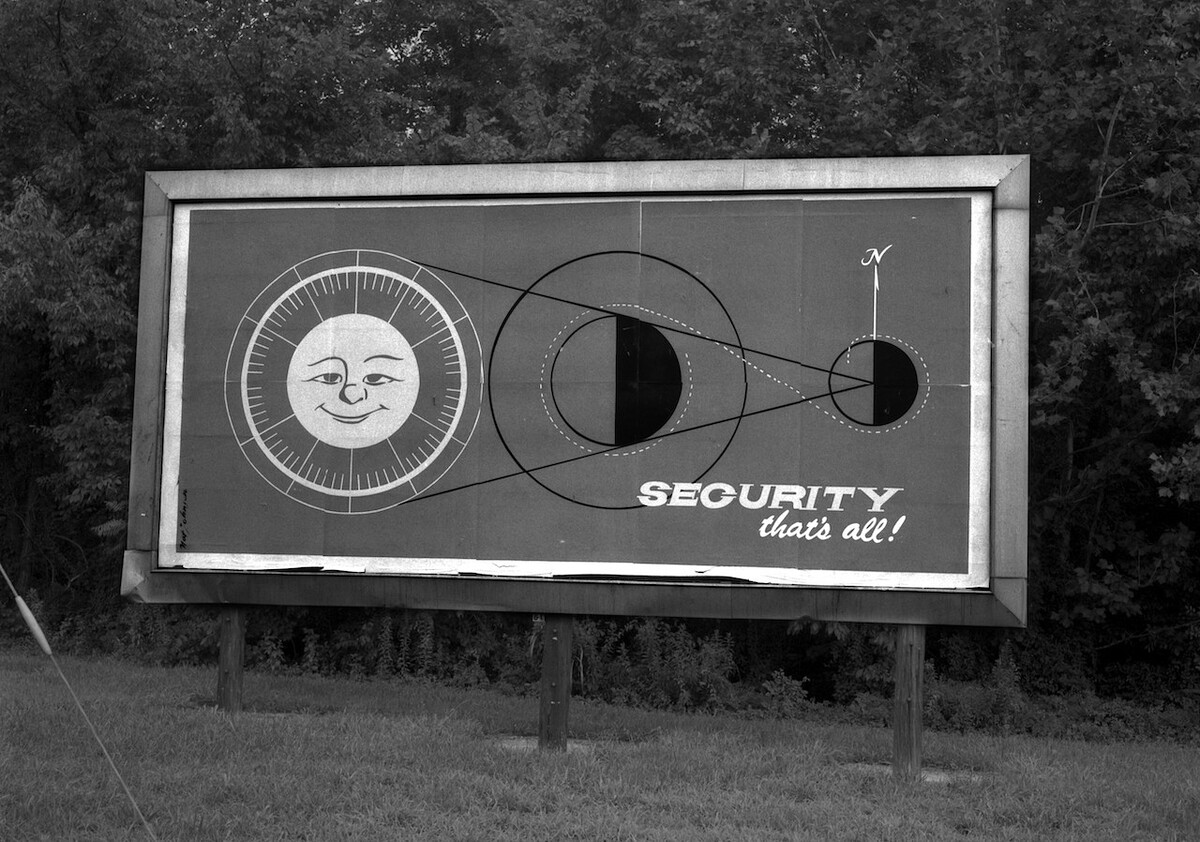

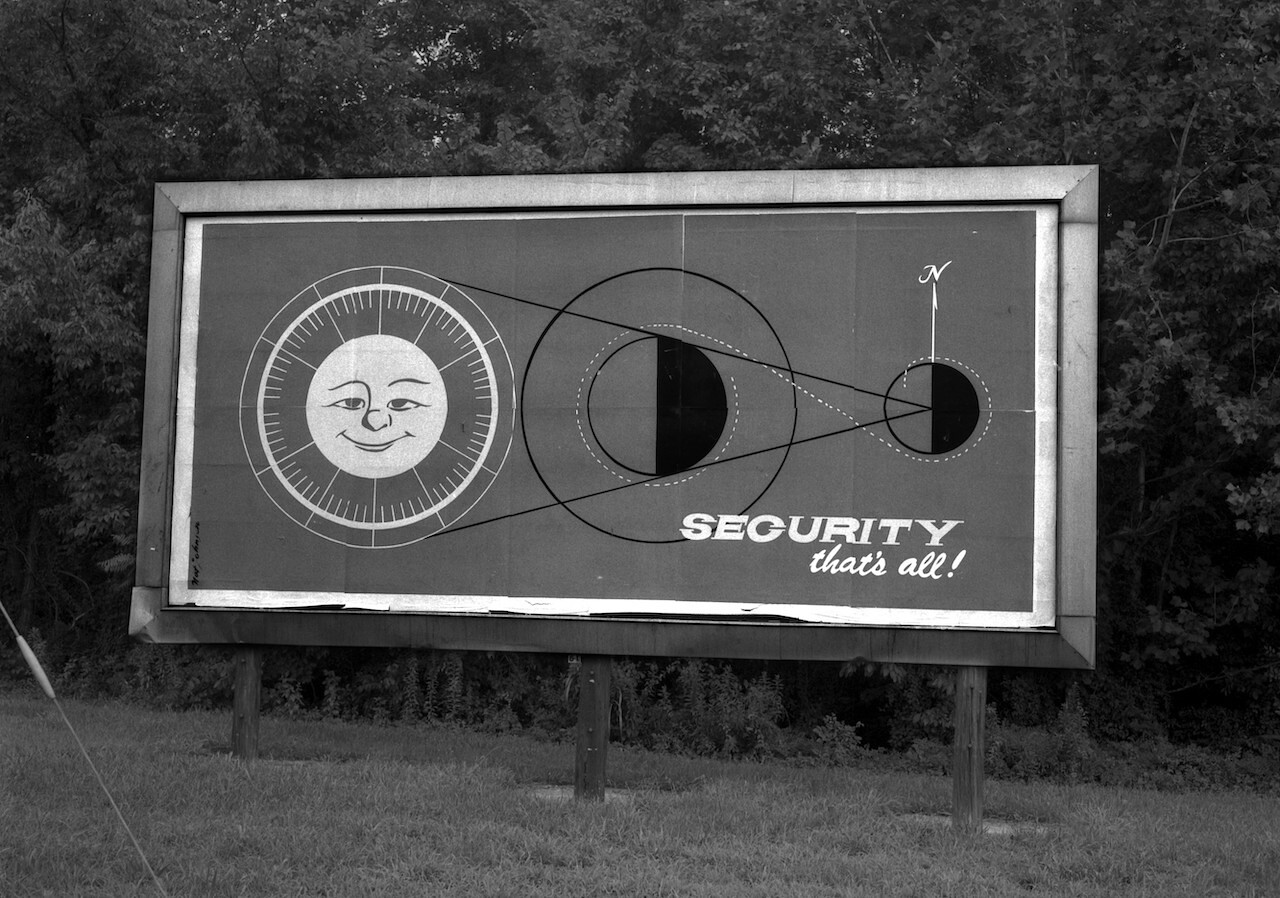

Security billboard at a former Manhattan Project site, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, 1970. Photo: US Department of Energy.

I believe I have understood our age as that of the absolute corruption of all ideas. Nevertheless, I am of good cheer: for I know that new love can come only from complete decay.

—Johann Gottlieb Fichte to Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi, March 31, 1804

0. Conspiracy—Pure Conspiracy!

In the spring of 1847, after much sustained coaxing, Marx and Engels agreed to join the League of the Just under one condition: that the League exclude conspiratorial thinking from its program. As Engels puts it, “Moll reported that they were as much convinced of the general correctness of our mode of outlook as of the necessity of freeing the League from the old conspiratorial traditions and forms.”1 Marx, a journalist at the time, saw his social role as enlightening his audience and doing away with any sort of workers’ conspiracy, which he never took part in himself.

The Communist Manifesto was written in a period known as the Vormärz, between the French revolutions of 1830 and the 1848 revolutions in Germany and France. Capitalist social forms had begun to emerge in large urban metropolises and the predominance of money society gradually took hold. The social categories of the old order were “creatively destroyed” by new, capitalist ones, which meant that old class alliances began to dissolve and new ones crept in to take their place. Amidst such confusion, conspiracies abounded, but there was no clear way to judge alliances.

Marx and Engels wanted to make a break with all of capitalist society, but they thought doing so required something scientific rather than hasty plots to “launch a revolution at the spur of a moment.”2 Marx and Engels’s rejection of conspiracist immediatism might have been due to their own version of a conspiracy theory concerning historical development: namely, the belief that “the irony of history” would eventually “turn everything upside down.”3 It was Walter Benjamin who launched the most well-known critique of this historical determinism in Marx, saying that “the lit fuse must be severed before the spark reaches the dynamite.”4 It wouldn’t be enough to simply wait for history to run its course—the time to act was now.

Even though they wanted to go beyond conspiracy, Marx and Engels seemed unwilling to do away with its rhetoric altogether. We all know how The Communist Manifesto begins: the ghost of communism and a plot to snuff it out by a “holy alliance” (Hetzjagd) that Engels had once termed a conspiracy.5 The program of this manifesto was to take what had appeared as ghostly and to construct it as Geist (spirit). In this sense, we can say that The Communist Manifesto was the determinate negation of conspiracism, which is to say that it attempted to overcome the impulsive nature of workers’ conspiracies by embedding them within a long-term perspective that would emphasize their opposite—a plan that took the laws of history into account. The intended effect was to forge a new logic to give shape to disputes between individuals, casting them anew as disputes between classes, thereby maximizing participation in the conflict. To that end, class and class interest became logical and practical categories for steering proletarian antagonism for the benefit of the class as a whole rather than small sects of rebels.

Despite his scorn for those he called in France the conspiratorial bohème—who he lumps in with prostitutes and thieves6—Marx admired the Russian variant of conspirators who made up the revolutionary group People’s Will, founded in 1879. The group’s program included “terrorist activity” aimed at “annihilating the regime’s most obnoxious personalities” and “destroy[ing] the aura of government power; to give constant proof of the possibility of struggle against the regime.”7 Marx lauded the group’s heroism and, according to Marxist sociologist Teodor Shanin, had “sharply turned against their critics.”8 Contrary to those for whom Marxism is a doctrinaire activity of observing and commenting on economic trends and using this as a “license to do nothing,”9 Marx insisted that it was people themselves—through revolutionary praxis—who change circumstances.10 In that sense, Marx and Engels’s determinate negation of conspiracism consisted of their own plan to do away with wage labor and the impoverished society it has created.

Marx’s views, we can safely say, oscillated between a Hegelian program of gifting the proletariat its own logic and an endorsement of revolutionary deeds that did not necessarily “keep themselves within the limits of the logically presumable.”11 In what is undoubtedly intended as a similar gesture for our post-enlightenment age, an anonymously authored book bearing the enigmatic title Conspiracist Manifesto was recently translated from French by the estimable Robert Hurley and published as a part of Semiotext(e)’s Intervention Series. The foreword to the “American” version sets out the following program for the work: “May the publication of this book in English help to reframe those categories and refine our comprehension of the nightmare into which we have been plunged.”12

1. Madness: The First Step Towards a Cure

In the lead-up to the book’s publication, all kinds of rumors and allegations were spread online about its nefarious content—no doubt by some people who hadn’t bothered to read it. Expecting to open up the book and read the worst, I was delighted to find that it instead contains a compelling tale of lies and deception, as well as a plan for redemption, all written in a passionate language that approximates what Dante called “the vulgar.” Indeed, the prose style of the book is more reminiscent of Baudelaire’s Paris Spleen than any political tract.

Conspiracist Manifesto shifts genres between critique, poetry, detourned quotes, historical narrative, and strategic analysis, all paired with a selection of images and memes. With its persistently carnivalesque tenor, the book deflates rather than inflates the concept of conspiracy. In other words, it implies that behind the conspiracy theories scattered throughout its pages—many of which point to rather banal power games with no deeper significance—there is just emptiness; no plan, no omnipotent world leader. The book’s secret lesson might be that the throne of power is empty, which is to say that everything really is up for grabs. The warnings in the book are not aimed at instilling a paralyzing fear or a pathological paranoia: instead, they seem to suggest that those determined to put their passion for justice into action might be surprised at how fragile the status quo really is. Still, such action is most likely to succeed if accompanied by a plan—a conspiracy—to steer the anarchic flows of the world towards something we could call communism.

The question is whether the book is a sign of a more general turn towards the need for conspiracies in the form of concrete plans for how we can construct a desirable future. The instability that pervades a world of nationalist frenzy, resurrected industrial policies, and threats of a new global war creates the hope both on the right and the left that the future can be organized step by step by dismantling and exposing the logic of the present. Reading the book, one can almost hear the words of the late Mike Davis, who insisted in one his last texts that “never has so much fused economic, mediatic and military power been put into so few hands. It should make us pay homage at the hero graves of Aleksandr Ilyich Ulyanov, Alexander Berkman and the incomparable Sholem Schwarzbard”—three conspirators who struggled against the nihilistic war machine of the modern nation-state.13 On the other side of the political spectrum, Ross Douthat speculates in the New York Times that the American government wants the public to believe in UFOs in order to create confusion and havoc.14 Conspiracies are everywhere in this age of mercenary mutinies and blown-up pipelines.15 Now some US government officials believe that Covid-19 was a Chinese lab leak, whereas Jeffrey Sachs argued in 2022 that it could even have American origins.16 By reducing conspiracies to a struggle for mundane economic and political interests, this anonymous manifesto shows the need to plan how we can move away from the bleak world it depicts. Against the conspiracies of the market and war, it urges us to plan a liveable and desirable future. Our enemies are organized. Doing away with them requires that we have a plan of our own.

The book’s final pages contain the skeleton key to understanding the specific type of conspiracy it calls for: “Above all resist the temptation to close oneself into a group.”17 This differs significantly from the kind of conspiracy advocated by influential nineteenth-century French revolutionary Louis Auguste Blanqui. What Conspiracist Manifesto calls for is not the activity of small, closed, Blanquist sects attempting to carry out coups in favor of partial interests, but rather an open conspiracy that involves transmitting an analysis with a broad appeal, inviting participation from a heterogenous and nonspecialized crowd. The goal is to “organize encounters … And in this way, [put] together a conspiratorial plan that will go on spreading, branching, complexifying, deepening.”18

The book’s French title is not “Manifeste Complotiste,” which would be the conventional equivalent to “Conspiracist Manifesto,” but rather “Manifeste Conspirationniste.” The use here of the adjective form of “conspiration” (literally “breath together”) evokes the pneuma—the unitary substance that, for the Stoics, fills the world, connecting everything. Breathe what together? Tear gas. Conspiracist Manifesto seems to have been written in the first instance for the Yellow Vest movement in France. This is paradoxical, since the gilets jaunes were anything but a conspiracy. They were a spontaneous movement with no clear agenda that emerged almost automatically in response to rising gas prices, before being put to rest by the 2020 lockdowns. The movement was typical of many of the so-called “non-movements” of our age in that, while it seemed capable of leveraging insurrectionary force against the government, its politics were difficult to pin down.19 Some have attributed to the movement a limited politics of lashing out against unfair government policy, labelling it “inter-classist”—more a populist movement than a class struggle.20 Contrary to such denunciations made by an enlightened vanguard, Conspiracist Manifesto situates itself directly in the midst of the Yellow Vest crowd. Rather than critique or denounce the movement, it seeks to intervene from within the movement in order to clarify the stakes and propose a strategy for advancing towards a revolutionary horizon.

From this perspective, many of the vague, perhaps misguided beliefs of the proletariat can be welcomed as stages or even errors of consciousness in an ongoing insurrectionary odyssey. Through successive battles with real class adversaries—the police, politicians, intellectuals who respond cynically to uprisings—these beliefs will undergo a series of negations which will make them more and more determinate. Conspiring is about mixing impure elements together; that’s why Marx called his conspiratorial rivals “alchemists of the revolution.” From this angle, Conspiracist Manifesto is unique among communist books in empathizing with the insanity of many proletarians’ misguided motives, which often take the form of conspiracy theories. Indeed, it welcomes this insanity in a bid to incorporate it all into a revolutionary conspiracy. This is perhaps its own determinate negation of conspiracism.

Those who hit the streets during the George Floyd rebellion were no strangers to conspiracy theories. Contrary to those who claim that “no proletarian insurrection” has ever been “driven forward by myth and mystification,” it must be insisted that the George Floyd rebellion was a carnival of madness driven by sublime freaks from every circle of hell.21 Absent any coherent communist line to steer these movements, the belief in some myth or conspiracy theory is likely to be a common, even default motive for today’s uprisings. Proletarians believe the craziest shit. On this note it is worth quoting Lenin at length:

Whoever expects a “pure” social revolution will never live to see it. Such a person pays lip-service to revolution without understanding what revolution is.

The Russian Revolution of 1905 was a bourgeois-democratic revolution. It consisted of a series of battles in which all the discontented classes, groups and elements of the population participated. Among these there were masses imbued with the crudest prejudices, with the vaguest and most fantastic aims of struggle; there were small groups which accepted Japanese money, there were speculators and adventurers, etc. But objectively, the mass movement was breaking the back of tsarism and paving the way for democracy; for this reason the class-conscious workers led it.22

The lesson here is that anyone taking a position within these movements must be careful not to side against delusional beliefs, or even madness; the point is to find a way to let it breathe, for madness can be a miraculous weapon. Poverty causes a soul-destroying form of madness. Trying to pass a smog test in California is madness. Madness can be an intoxicating form of class hatred that drives proletarians to risk everything even when they have little chance of winning against their adversaries. This is why communists must have tools for working with it.

Freud called delusions an attempt at a cure; they initiate the process of making sense of experiences that cannot be processed otherwise. Nobody chooses to be delusional—something to keep in mind when interacting with proletarians who might resort to conspiracy theories to explain their motives for opposing the ruling class. That’s not to say that delusions can’t be wrong or incredibly harmful; the point is to develop a new analytic method of listening and working with these beliefs rather than positioning oneself a priori against them. Perhaps one shortcoming of the Conspiracist Manifesto is that it neglects to formulate such an analytic method—something that would work to counter the obvious fact of identification and belief and lend conspiratorial thinking an ever more exact articulation, preventing a total break with reality.

2. From Biopolitics to Noopolitics

Conspiracist Manifesto launches a rigorous critique of much of the radical left for its failure to take into account a critique of biopolitics during the pandemic. While the concept is most closely associated with Michel Foucault, it is perhaps Marx who provides the most pithy description of what’s at stake in biopolitics: “Not only the illness, but even the doctor is an evil. Under constant medical tutelage, life would be regarded as an evil and the human body as an object for treatment by medical institutions. Is not death more desirable than life that is a mere preventive measure against death?”23 Beginning with the history of medical interventionism, Conspiracist Manifesto advances a historical account of the ways in which capitalism interferes in and manages the production of human life and social populations. If the authors hold fast to this line of thinking, it is because for them, revolution is not merely a question of adjusting the economy; it involves the transformation of the human species itself: for them, revolution is first and foremost an anthropological question that entails the production of new forms-of-life.

To that end, the book constructs what can be termed a negative anthropology of the human. It was the German philosopher Günther Anders who first coined this term to describe the human being as a “fundamentally unhealthy being who cannot be healthy and does not want to be healthy, that is, the undefined, indefinite being, which it would be paradoxical to want to define.”24 By emphasizing the way in which human beings are constructed by governance, Anders suggests that the human has no fixed essence, and can thus both transform itself and be transformed by its environment. In this regard, Conspiracist Manifesto goes beyond the category of mere biopolitics and advances a critique of what has been called noopolitics, or psychopolitics—techniques of control aimed at colonizing Geist (both mind and spirit).

The authors use the pandemic to demonstrate that governance under the state of exception is issued as a series of double binds—“contradictory injunctions”25—that cumulatively destroy the grounds for individual rational thought. The end result is a form of madness among the population that is ordinary rather than pathological. This war on meaning-making undermines the mental health of the populace, as witnessed in, for example, the mental health crisis plaguing the US. Consonant with this, the Manifesto’s wager is that social antagonism runs through each individual: the theater of operations for contemporary class war is the soul. The book contends that the soul is not an individual property but a “commons” of the collective experience of the world, the cosmos, and the positive affects that arise when interconnections are recognized.

It is perhaps worth drawing up a balance sheet of the impacts of the pandemic three years after the fact. While the lockdowns saved lives, for many people they also severed the few tenuous social bonds they had left. The consummation of atomization has had many lasting effects that remain to be processed. There was also a marked increase in domestic abuse. A study put out by the London School of Economics, citing the New York Times, reports that “countries worldwide such as France, China, India, Spain, and the United Kingdom have witnessed an increase of more than 20% in domestic violence emergency calls.”26 These impacts of the lockdown are all the more lamentable when you realize that imposed social isolation was not the only effective means to combat Covid. As doctor, historian, and lifelong autonomist Karl Heinz Roth demonstrates, there were many practical and conceptual alternatives to the dominant lockdown doctrine. He argues that epidemiological interventions—which essentially relied on targeted preventative and protective measures—were essential for stopping the spread, but the same is not true of the lockdowns, which were intended primarily to showcase the absolute power of the ruling class in a crisis situation. Indeed, many of the lockdown measures exacerbated the negative effects of the pandemic. For example, parks and outdoor spaces were closed worldwide “even though it is well known that Covid is carried by exhaled or coughed up particles which quickly evaporate outdoors.”27 As a result, writes Roth, the enforcement of blanket lockdown measures provided no specialized protection for those groups that were most at risk: the elderly and the chronically ill. Prioritizing protection and care for these groups would have drastically decreased hospitalizations and deaths. The failure to follow these targeted measures devastated the social fabric by prioritizing policies of confinement.

But Conspiracist Manifesto sees this undoing of the social as an opportunity for redemption. In a stunning dialectical inversion, the book’s final chapter argues that the enforced isolation and attendant destruction of the social that resulted from the pandemic measures put a form of collective existence to rest that is not worth saving. In opposition to an abstract form of solidarity based on one’s belonging to the same society, it posits a concrete form of solidarity as an obligation to love the other based on shared participation in a common conspiracy.

3. A Reality of Souls

In his 1962 preface to Theory of the Novel, György Lukács writes: “The immediate motive for writing was supplied by the outbreak of the First World War and the effect which its acclamation by the social-democratic parties had upon the European left.”28 In its original format, the book was to contain a series of dialogues in which “a group of young people withdraw from the war psychosis of their environment, just as the story-tellers of the Decameron had withdrawn from the plague.”29 Theory of the Novel charts how the transition from the epic to the novel corresponds to a transition from a Gemeinschaft (community) to a Gesellschaft (society). In the final chapter of the book, Lukács claims that Tolstoy represents the first hint of overcoming the European Romantic tradition insofar as his novels can be said to go beyond the social forms of life. Rather than acquiesce to depicting standardized social figures, Tolstoy’s novels point to “the utopian refusal of the conventional world objectivized in an actually existing reality.”30 Tolstoy’s utopia was found outside of society, in nature.

According to Lukács, Dostoevsky takes things one step further. Unlike Tolstoy, he does not write novels. Instead, Dostoevsky’s works are closer to epics: they portray a utopian world of a “pure reality of souls,” a world that goes beyond nature in its opposition to culture, as well as beyond modern culture in its dualism (individual vs. community) and alienation.31 This utopian world amounts to a new “transcendental topography” beyond the metaphysical homelessness of the Western world. In this regard, Dostoevsky’s writings offer a prospect of utopian redemption against the social. In other words, redemption won’t be found in realizing the social identities foisted upon us by society, but instead by abandoning them. While there are meaningful social bonds that are worth preserving, what’s been destroyed by modern society are the forms of tradition that would give those social bonds a larger context and meaning. In his notes for a never-actualized book on Dostoevsky, referenced in the Conspiracist Manifesto, Lukács gives an example of what it means to seek redemption outside the forms of the social:

The setting of the reality of souls as the only reality also means a radical shift in the sociological representation of man: at the level of the reality of souls all those fetters are detached from the soul which otherwise fixed it to its social position, class, descent, etc., and new, concrete, soul-to-soul contact takes their place.32

Conspiracist Manifesto champions such bonds cultivated through shared experiences of struggle, and encourages the development of what it calls a “communism of thought.” In Dostoevsky’s words, this would be “a thought stronger than all calamities, crop failures, torture, plague, leprosy, and all that hell, which mankind would have been unable to endure without the thought which binds them together, guides their hearts, and makes fruitful the wellsprings of the life of thought.”33

Lukács wrote all of this under the spell of what he considered the heroic deeds of bands of Russian terrorists in the lead-up to the Russian Revolution. He was, much like Marx before him and his contemporary Ernst Bloch, enraptured by the happenings in Russia. Lukács was keen to translate a selection of writings published in Russia from 1904 to 1907 because, as he put it, these terrorists represented “a new type of man.”34 Lukács was particularly enthusiastic about a novel called The Pale Horse by V. Ropshin, which fictionalizes the real-life actions of a certain Ivan Kalyayev, who was part of the Socialist Revolutionary Party—incidentally, the successor to People’s Will, the group Marx was so keen to defend. As part of this group’s program, in February 1905 Kalyayev set out to murder the Grand Duke Sergei, but aborted his initial attempt after seeing that the carriage the Duke was travelling in contained a child. Kalyayev was unable to justify murdering the innocent, so he decided to wait to carry out the act. Two days later, he did so successfully when the Duke was just outside the Kremlin. Kalyayev was immediately apprehended, arrested, and hung.

The final chapter of Conspiracist Manifesto bears the Olympian title “We Will Win Because We Are Deeper.” Much like Theory of the Novel, the book seems to have been written in a gesture of withdrawal from the left, which it sees as uncritically lending its support to the war of psychological destruction underway. The Manifesto posits the figure of the anti-fascist resistance fighters of the French Maquis as a historical reference point for the kind of resistance it calls for. The Maquis was a clandestine network of draft resisters under the Vichy regime in France who organized in cells to carry out attacks on the forces of the fascist regime. According to Conspiracist Manifesto, this is the organizational form that best embodies Lukács’s yearning for a reality of souls, a concept taken up in its final pages. Whereas cybernetic governance treats individuals as black boxes that are connected only as exteriorities—empty shells—a contemporary communist resistance would entail concrete contact between souls. In the wake of society becoming oversaturated with hatred and enmity and thus irreparably fragmented, it asks us to imagine a nonsocial form of communism. In this sense, we can—alongside Fichte—rejoice at the ongoing social decay and the fact that the pre-pandemic “normal” will never be fully restored.

With this nonsocial form of communism, the manifesto situates itself in a trajectory set out by Jacques Camatte with his injunction: “We must leave this world.” As Camatte explains: “When Amadeo Bordiga said that we had to behave as if the revolution had already happened, he was calling for a specific ‘ethos,’ different from that of epigones wallowing in Lenino-Trotskyist behavior.”35 Recently, the outmoded politics that form the backbone of Andreas Malm’s green-Bolshevist agenda have wooed popular audiences by calling for acts of sabotage in defense of the earth. While such acts are entirely justified, the urgency of the ecological crisis does not magically make anachronistic organizational forms relevant again.

Against such nostalgic fantasies, Conspiracist Manifesto asks us to elaborate a conspiratorial ethos grounded in organizational forms more suited to present struggles. As mentioned above, its organizational model is a more open and fluid form of Blanquist cells, where partisans are careful not to close themselves off into fixed, insular groups. While some may see this as a regression in the logical progression of struggle, it is worth recalling that “the conspiratorial organisations of Blanqui [gave] way to mass working-class organisations. Many of Blanqui’s followers went on to join the Socialist Party (SFIO), the majority of which, in 1920, formed the French Communist Party.”36 Conspiracies are an important antidote to the dreadful cynicism and wait-and-see attitude that characterizes our current era of proletarian disorganization. Alongside this conspiring, the book asks us to reconstruct habitable worlds. In the twentieth century, communism named a concrete nexus of worlds one could participate in. If you were a communist in Western Europe, you could travel to Eastern Europe and learn German or Slavic languages. You could go to Cuba. You could build roads in Yugoslavia, Albania, or China. Today such worlds remain to be built. Conspire, therefore. Conspire to plan a life beyond the lawlessness of market society. Conspire to invent a new form of participation in the world from out of this precarious world of war and strife. Conspire for peace, conspire for love.

Friedrich Engels, “On the History of the Communist League,” in Marx and Engels Selected Works, vol. 3 (Progress Publishers, 1970) →.

Karl Marx, “Les Conspirateurs, par A. Chenu,” in Marx & Engels Collected Works, vol. 10 (Lawrence & Wishart, 1978), 319.

Friedrich Engels, “Introduction to Marx’s Class Struggle in France,” in The Revolutionary Act: Military Insurrection or Political and Economic Action? (New York News Company, 1922) →.

Walter Benjamin, Werke und Nachlaß. Kritische Gesamtausgabe 8: Einbahnstraße (Surkampf, 2009), 50. My translation.

Marx & Engels Collected Works, vol. 10 (Lawrence & Wishart, 1978), 14.

Marx, “Les Conspirateurs, par A. Chenu,” 319.

“The People’s Will: Basic Documents and Writings,” in Late Marx and the Russian Road: Marx and the “Peripheries of Capitalism,” ed. Teodor Shanin (Monthly Review Press, 1983), 210.

Teodor Shanin, “Late Marx: Gods and Craftsmen,” in Late Marx and the Russian Road, 21.

Shanin, “Late Marx: Gods and Craftsmen,” 21.

Karl Marx, “Theses on Feuerbach,” Marx & Engels Collected Works, vol. 5 (Lawrence & Wishart, 1975), 4.

Karl Marx, “Critique of the Gotha Programme,” Marx & Engels Collected Works, vol. 24 (Lawrence & Wishart, 1989), 94.

Conspiracist Manifesto, trans. Robert Hurley (Semiotext(e), 2023), 17.

Mike Davis, “Thanatos Triumphant,” Sidecar, March 7, 2022 →.

Ross Douthat, “Does the U.S. Government Want You to Believe in U.F.O.s?” New York Times, June 10, 2023 →.

Conspiracist Manifesto, 361.

Conspiracist Manifesto, 361.

The term “non-movements,” which comes from Asef Bayat, was taken up by Endnotes in their essay “Onward Barbarians” to describe the unorganized nature of contemporary anti-government protests →.

Temps critiques, “Sur le mouvement des Gilets jaunes,” Temps critiques, no. 19 (December 2018) →.

Research and Destroy, “The Dilemma,” Ill Will, January 24, 2021 →.

V. I. Lenin, “The Irish Rebellion of 1916,” Irish Marxists Review 4, no. 14 (November 2015) →. Emphasis in original.

Karl Marx, “Rheinische Zeitung No. 132, Supplement May 12, 1842,” Marx & Engels Collected Works, vol. 1 (Lawrence & Wishart 1975), 162.

Günther Anders, Die Antiquertheit des Menschen II (C. H. Beck, 2014), 221. My translation.

Conspiracist Manifesto, 170.

Ria Ivandić, Tom Kirchmaier, and Ben Linton, “Changing Patterns of Domestic Abuse During Covid-19 Lockdown,” Center for Economic Performance, London School of Economics, November 2020 →.

Karl Heinz Roth, Blinde Passagiere: Die Coronakrise und die Folgen (Verlag Antje Kunstmann, 2022), 303. My translation.

Georg Lukács, Theory of the Novel: A Historico-philosophical Essay on the Forms of Great Epic Literature, trans. Anna Bostock (MIT Press, 1971), 11.

Lukács, Theory of the Novel, 11–12.

Lukács, Theory of the Novel, 144.

Lukács, Theory of the Novel, 152.

Georg Lukács, Dostojewski: Notizen und Entwürfe (Akadémiai Kiadó, 1985), 29. My translation.

Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Idiot, trans. Larissa Volokhonsky and Richard Pevear (Vintage, 2012), 379.

Lukács to Paul Ernst, April 14, 1915, George Lukacs: Selected Correspondence 1909–1920 (Columbia University Press, 1986), 245.

Jacques Camatte, “Scatologie et résurrection,” Revue Invariance →. My translation.

Doug Enaa Greene, Communist Insurgent: Blanqui’s Politics of Revolution (Haymarket, 2017), 138–39.