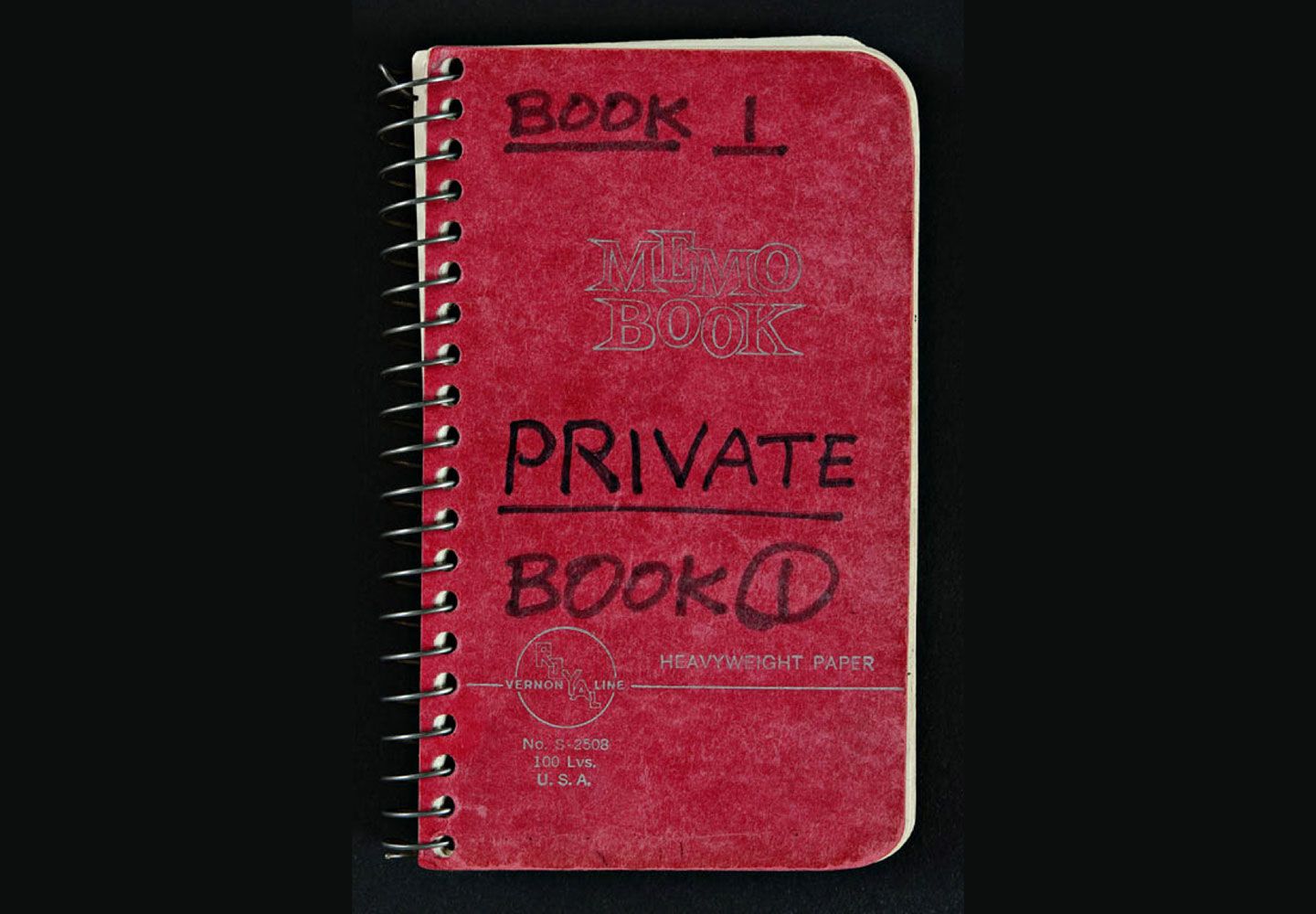

Meeting space at the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center, “How to Work together?” curated by Reem Shadid and Yazan Khalili, part of Qalandiya International 2018.

In the following notes, the IMAGINART research group tackles the promises and predicaments of collective instituting in the fields of art and culture. If there is more space today for both collectives and institutional work in a globalized art field, (how) is this work changing the nature of (cultural and other) institutions? We believe this art/institutional work is all the more relevant because traditional (state) infrastructures are globally undergoing massive transformations, teetering if not crumbling or failing outright. Firmly embedded in local genealogies of grassroots activism and anti/decolonial counterculture, and yet simultaneously interconnected, our case studies range from Palestine to South Africa, Indonesia, Hungary, the autonomous region of Rojava in northern Syria, Peru, and Italy. We are not interested in producing a normative, abstract theory of creative institutionalism, which would diminish the vibrancy, richness, and urgency of our stories. What we offer here is a transnational, translocal analysis—both comparative and connective—of diverse artist- and cultural worker–run projects that are self-organized, largely horizontal, and politically engaged, and which mobilize a variety of artistic practices.

This collaborative essay explores artist projects that experiment with alternative welfare provision; others that resist colonialism through cultural regeneration and the imaginative recuperation of precolonial cultural forms; yet others that make visible and work with long-silenced, censored histories of marginalized communities, pointing to other potential futures; and finally others that use, mock, and hack mainstream cultural institutions to foster the movement of experimental institutionalism. They all respond to a basic lack of the state, or to its failure to establish just and inclusive institutions, or to outright state (racialized, classed, and gendered) oppression, which can be due to (post)colonial, postsocialist, or neoliberal processes of politico-institutional transformation. The actors in this movement are a diverse group of people who come together into a kind of social bloc: artists and cultural workers, activists and scholars who have experienced and/or are fighting against multiple intersectional forms of violence committed by states and capital. How do artists and cultural producers work to reinvent public institutions by way of collective “art” practice? We have identified a set of common strategies these projects use to create institutions that are just and caring, and have organized these notes accordingly. Can we see these experiments as sites of an emerging political imagination that goes beyond institutional innovation?

Welfare: Art Commoning

The first strategy of creative institutionalism that we want to flesh out is art commoning, that is, the collective, horizontal reorganization of communities around the sharing of resources by means of artistic practices—with the aim of achieving well-being for all involved. This aim entails the establishment of institutions that are self-reflexive, flexible, and responsive to people’s needs, ultimately caring for those they cater to (often active members) as opposed to answering primarily bureaucratic logics. Our three cases studies, in Italy, Palestine, and Indonesia, offer examples of creative welfare provision based on experimental collaborative practices. The projects respond to either neoliberal policymaking that has progressively dismantled state welfare infrastructures (in Italy and Indonesia) or to very weak or absent ones. In contrast to the absence or neglect of state-run welfare, artist-created institutions of care build on informal networks and collectivized systems of support. As described below, the social experiments of cultural activists in Italy, the collective kitchen experience in Indonesia, and the healthcare scheme set up by the Sakakini Cultural Center in Palestine find common ground in promoting the physical well-being of their constituencies through the combination of commoning and artistic practices. Each commoning practice, however, is contextually bound to specific local legacies of grassroots organizing and sociopolitical movements.

How can culture be activated as a commons, contributing to society’s well-being? From the late 2000s onwards, Italy witnessed a political movement for the commons (Movimento per i beni comuni), in which cultural workers played a major role. This movement intersected with the various Occupy social movements that struggled against neoliberal policymaking and the austerity measures governments imposed in response to the financial crisis. But it also intersected with a longer countercultural tradition that has been evolving in Italy since the late 1960s. Underpinned by autonomist thinking and practice (Autonomia Operaia, or Workers’ Autonomy), this tradition has been centered in squatted urban spaces. In the early 2010s artists, activists, and cultural workers took it upon themselves to occupy and recuperate abandoned buildings and convert them into an infrastructure of care and support, based on values such as mutualism, solidarity, and the struggle against exploitation and precarity, particularly of cultural labor.

Teatro Valle Occupato (TVO), located in a former opera house in Rome that had been closed and defunded by the municipality, was the most influential of this new wave of cultural occupations. A space for cultural and political experimentation, TVO established an initial foundation for the commons in Italy, which was later recognized by the Italian state and continued after the squatters were evicted. For TVO,

the common good is not given, it manifests itself through shared action, it is the fruit of social relations between peers and an inexhaustible source of innovation and creativity. The common good comes from below and from the active and direct participation of citizens. The common good is self-organized by definition and defends its autonomy both from the private ownership interest and from the public institutions that govern public goods with private logic.1

Culture is a common good, and as such is a source of welfare for those who produce and share it. In Italy, all the cultural occupations functioned according to this same principle, and the accompanying practices centered on the assembly as the primary form of self-government. All had rich cultural programming with an expanded meaning and impact. For example, Milan’s MACAO decided to horizontally distribute the profits generated by its programming. Between 2014 and 2019, MACAO set up an alternative currency, a crypto wallet, and a Bank of the Commons, which together comprised a system for valuing and remunerating members’ work.2 Asilo Filageri in Napoli understood itself as a “cultural laboratory” where the means of art and cultural production were shared for the benefit of all involved. Art is not autonomous but a “zone where the political sphere can express itself,” the site for an “emotional experience,” fostering relational connectivity and political experimentation.3

Spaces and communities such as TVO, MACAO, and Asilo were all born out of this commoning movement and activated processes of intellectual exchange and collective thinking around issues of alternative welfare. Most of the spaces were evicted—and many of their members arrested—but they left tight-knit communities that continued to work and think together. During the pandemic, when cultural workers faced tremendous challenges with very little work and state support, this community of communities produced a programmatic document demanding an unconditional universal basic income (UBI) for artists and art workers. The manifesto, Art for UBI, declares that the “claim for UBI, being grounded in the ethics of mutual care, is art workers’ most powerful gesture of care towards society.”4

(How) can an art institution expand to become a welfare infrastructure? Located in the occupied West Bank city of Ramallah, the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center (KSCC) worked towards this goal. For Lauren Berlant, practicing the commons goes beyond sharing resources and spaces in egalitarian ways, for it should be mobilized “as a tool, and often a weapon, for unlearning the world” and as “a pedagogy for unlearning normative realism and rethinking structure as something in constant transition.”5 It should be a space of critical engagement and productive contestations whereby the act of troubling challenges established power structures and norms, and enables transformative practices and political imagination. The initiatives of KSCC constituted such a troubling, troubled commons. The center was and is one of a network of Palestinian cultural organizations that have cocreated an informal infrastructure of cultural production and management in a context marked by the persistence and expansion of the Israeli occupation and the failure of the Palestinian Authority and the Palestinian state project generated by the 1990s Oslo Accords.6 This network of organizations has been organizing the Palestinian biennial, Qalandia International, since 2012. KSCC’s contribution to the most recent edition (2018)—on the theme of solidarity—was a project titled Debt. This project reflected on how cultural institutions could be redirected towards the well-being of their constituents: employees, artists, and cultural producers, and other freelancers such as translators, producers, technicians, etc. In other words, participants asked how the institution can expand into a commons, to be utilized to question limited access to resources and provide a form of affordable welfare such as health insurance and legal aid. The result of this project was an institutional experiment to offer health insurance to constituents, employees, and the wider community of artists and cultural practitioners and their family members.

In order to do so, KSCC had to recalculate, redirect, and extend its resources. The institution had to extend beyond itself, to trouble its boundaries, means, and goals. KSCC called this approach “inverted resources”; it saved nearly 70 percent on the price of individually bought insurance. For a financially struggling institution such as KSCC, providing healthcare meant rethinking how commonality can be practiced within rigid administrative structures, and how an institution’s power can be mobilized as a resource that the community can tap into and benefit from. In other words, by collectivizing access to the power and assets that exist within the institution’s legal and administrative modes of existence, the institution was transformed into a support infrastructure for an extended community. Institutional power was transformed into commons, troubling neoliberal institutionality.

How long do such projects of care last? How sustainable are their precarious infrastructures? This was a challenge for the collective kitchens movement in Indonesia. Amidst a broader societal upheaval, this movement emerged during the Covid-19 pandemic, but it had a much longer genealogy. Indeed, the ties between the activists involved went back to the student struggle of 1998 to remake Indonesian society and the state and at the end of Suharto’s authoritarian regime. A tradition of art collectivism and self-organizing played and still plays an important role in this struggle for deep democracy, which continues to the present day, as its objectives have not been achieved.7 Artist and cultural-worker collectives such as Kunci, ruangrupa, and Taring Padi have fought to reclaim public space and transform it through culture. In doing so, they have created a vibrant cultural space beyond both state and NGO initiatives. The crisis generated by the pandemic gave them a new impulse and repurposed their practices anew towards the provision of basic care, which in turn triggered a broader discussion about commoning strategies.

The longest-running kitchen of the pandemic movement was East Java’s Pawon’e Arek-Arek (PAA, or “our kitchen”), which emerged from an artist collective called Kerjasama 59 (“working together”). Apart from the kitchen, this collective also organizes a vegetable garden and a film program. Like similar experiments, such as Jogja Food Solidarity in Yogyakarta, PAA provided food for community members in its neighborhood. Members worked on a voluntary basis, funding their activities through donations. This case shows how experimenting with care may emerge as an unexpected opportunity in the context of a crisis such as the pandemic. But a caring infrastructure only lasts as long as there is a conducive environment, nourished by people’s labor, energies, and well-being.

Cultural theorist Melani Budianta coined the term “emergency activism” to describe short-lived activities that proliferate in emergency environments, such as that of immediate post-1998 Indonesia or the pandemic.8 One member of our collective, Nuraini Juliastuti, sees this as “fast activism,” which is akin to repairing the holes of a damaged social fabric.9 Each activist project attempts to sew meaning into these holes, to make sense of and mend current conditions. But after one hole is fixed, many more holes are discovered piercing the same fabric. Activists commit to these acts of quick repair, which reveal themselves as more and more demanding, ultimately constraining activists and the roles and responsibilities they hyperactively assume.

Many collective kitchens did not last long. PAA was the longest-running one, but it closed in December 2022. During an interview, the activists of Kerjasama 59 declared that they needed to take a break. Similarly, another project, Yogyakarta-based Ace House collective, became well known for its motto “seni juga butuh istirahat,” or “art needs some rest too.” These declarations point to the problem of activist exhaustion, the fatigue that comes from the work of the commons, which is far too familiar to many art and cultural activists. Fast activism springs from (a sense of) emergency, and yet istirahat, meaning “to pause,” is essential.10 Some pauses are short; others can be long. Yet, as the members of the kitchen collectives anticipated, there is a comeback.

Economies: (Re)turn to the Land

The second strategy of creative institutionalism is the imaginative reappropriation of cultural heritage in contexts where people’s relation to it has been ruptured. Often this reappropriation happens through a “return to the land,” both as physical space and as landscape of the imagination—as soil and heritage. Our two case studies unfold in areas of tense political struggle: Palestine and the autonomous region of Rojava in northern Syria. Here coloniality endures in its most brutal form. Despite significant differences, in both cases a national liberation front struggles against repressive state operations that not only target communities, livelihoods, rights, freedoms, and resources, but also carry out a relentless erasure of cultural practices and roots. In this context, cultural recuperation is national survival and a key tool of resistance.11 Such recuperation is poetic and self-reflexive as opposed to philologic and conservative because it makes space for experimentation and change. The “return to the land” is a cultural, artistic, and economic endeavor that aims to create collective spaces in which a community reinvents a lost or threatened heritage in the service not just of survival but of transformation—restoring, reinventing, and valorizing relations and not just objects or traditions. Reconfiguring a community’s relation to ancestral land through such creative heritage thus propels that community into the future. What is distinctive about the cases of Rojava and Palestine is that the process of cultural reappropriation in these places entails a strong economic dimension, or rather combines roots, culture, and resilient economies. How can returning to the land and its cultural traditions become a form of liberation, a moral economy, and a practice of counter-statehood?12

The Rojava Film Commune is a collective of filmmakers that produces and distributes films on Kurdish culture. They are reorganizing the infrastructure of filmmaking and film education in Rojava, which is a Kurdish-run autonomous area in Northern Syria. Founded in 2015, this organization relies on the collaboration of filmmakers and cinema lovers who “join the commune” on a voluntary basis from all four parts of Kurdistan—the latter being divided between different repressive states (not only Syria but also Turkey, Iran, and Iraq). The commune’s members do not ask for money, as their mission is to contribute to the national struggle for freedom. They want to be involved because the films represent their own “life, pain, and dreams” and offer a way to realize them.13 Films revolve around heritage, especially music, and are accompanied by music videos that expand and innovate folk genres. Production is communal, if supported externally by the federalist organization that acts as the plural government of Rojava, or by international donors. Filming takes place under harsh conditions, including war. Yet the spirit of the films is upbeat and future-oriented in what is ultimately a celebration of Kurdish endurance, resourcefulness, and sociopolitical creativity in the face of brutal violence.

The Rojava Film Commune performs a poetic return to the land through artistic strategies. Regenerating a strong link to the land via the production of creative heritage tightens strong social bonds within the broader community, whereby producers and users of culture blend into each other. Collectivity and communality are the guiding principles of this artistic production. “We work for the people and with the people, carrying the spirit of our culture. We do not make movies that our mothers do not feel, find themselves in, or watch … They [the community] see our project as part of themselves.”14 Indeed, the films are very popular and circulate widely on social media (and recently in art circuits too), especially the music videos. This accelerated circulation enables the commune to achieve its central aim of promoting Kurdish culture and resistance. It also generates revenue. Thus, producing and disseminating cultural heritage content through social and other media creates an economy. This positive economic externality in turn triggers a feedback loop that sustains further cultural production.

In Palestine this movement to (re)turn to the land by artists and cultural producers has taken on a literal form. One of the key actors here is the Palestinian Popular Arts Centre, a cultural organization that works to preserve and revitalize the local Dabke peasant folk dance. Recently, the center has started hosting a farmers market, activating and connecting farming cooperatives across the West Bank. This drive to reconstruct a strong link to both heritage and the land responds to a long history of alienation and dispossession. Indeed, the Zionist settler-colonial project has specifically targeted these links through the expropriation and colonization of Palestinian lands and the destruction or appropriation of cultural resources.15 In 1948, with the creation of the state of Israel, the Zionist movement conquered much of historic Palestine and forced Palestinian peasants into landlessness and exile. After the 1967 occupation of the remaining Palestinian territories in the West Bank and Gaza, the peasantry, which is the bedrock of Palestinian society, was forced onto a path of losing land—and their traditional lifeworlds—and of impoverishment and urbanization due to an expanding colonization.16 Over the years, the occupation has destroyed the local economy, resulting in economic dependency on Israel and international donors.17 This seemingly endless loss of land and a rooted culture has made Palestinians look at the old peasant lifeworld as a heritage to be cherished and cultivated,18 and, most recently, as the source of a new vitality, a new cultural economy.

There is a shift in the ways that such a return to the land is practically imagined. Historically, the preservation of Palestinian heritage has been intertwined with resistance against colonization—with staying put, firmly rooted in the soil. Dabke, for example, is a peasant dance style that was almost lost with the Nakba, or the 1948 Palestinian catastrophe and exile; it was popularized again in the 1970s and 1980s thanks to grassroots organizations such as the Popular Arts Centre, operating in the context of a reborn national liberation movement. Yet now, this return to the land is no longer implemented by preserving and reconstructing cultural heritage but by going back to farming itself. It is about (re)constructing an entire political, moral economy. The traditional moves of Dabke mimic a repertoire of rural gestures, such as ploughing and harvesting; bodies trained by such a dance are now back tilling the soil. Old and new farmers, and cultural practitioners turned farmers, work collaboratively and build support networks of co-ops that service them and distribute their products. They experiment with community-supported organic agriculture; customary, egalitarian ways of organizing life and work; vernacular building techniques; and agroecology. In so doing, they attempt to change the relation between villages and the city. Through this cooperative movement, they practice a new form of resistance and imagination through the land itself.

Land is at the core of the struggle for freedom from (settler) colonialism. Confiscated and occupied, long represented as eroding and even lost, land is now being reclaimed through commoning agricultural practices. Anti-colonial revolutionary intellectual Amílcar Cabral forcefully argued for a dynamic interplay between soil and social structures in the context of anti-colonial struggles. Cabral highlighted the revolutionary potential of reconnecting with the land as a deeply transformative, empowering process.19 In Palestine this call takes on a peculiar urgency in this historical moment. In the past thirty years, all of Palestinian society and the economy, including the cultural sector, has grown dependent on international donors. Thus, when cultural institutions activate this agricultural cooperative movement, they open up the possibility of an altogether different economic model, one less dependent on the donor economy and Israel. This new framework stimulates collaboration between farmers, local groups, and the wider community to develop ecological practices that are economically and socially sustainable. It also bridges the gap between the notion of culture as aesthetic production, and the notion of culture as everyday practice. Land here is no longer a metaphor, but vibrant, fertile matter, a generative medium through which social relations are reconstructed for a new future.

History: Anarchiving

The third strategy for creative institutionalism is anarchiving. The anarchive has been theorized by artist, curator, and scholar Carine Zaayman in relation to South African Indigenous projects of historical reconstruction.20 The term refers to those aspects of our lives that cannot, by definition, be archived, yet are central to how we remember the past and position ourselves in relation to it, creating a sense of continuity and easing unsustainable temporal fragmentation. These forms of extra-archival memory include, but are not limited to, oral histories and communal repertoires of social engagement. They are structurally excised from the archive as a national-colonial institution, pertaining to the articulated apparatus that has developed since the nineteenth century to aid national and imperial governmentalities.21 Our two case studies—one from Lima, Peru and the other from the Western Cape in South Africa—unfold in the context of two postcolonial states that entertain ambivalent relationships to the pre- and anti-colonial cultures and histories they allegedly celebrate and protect; despite conspicuous discontinuities, they silently reproduce key features of the oppressive colonial states they were established to dismantle. If official archives have not changed in the transition from colonial to postcolonial states, how do we work within, without, and around them to reconstruct the history of those who have long been denied an archive, and whose narratives have been erased in this process? How to work with/out colonial archives?

The Clanwilliam Arts Project was a yearly workshop, running from 1998 to 2018, for learners from the town of Clanwilliam in South Africa. It was led by Magnet Theatre in collaboration with students from the University of Cape Town’s drama, dance, fine art, and music departments, as well as independent practitioners in the arts. Each year these practitioners identified a story from the Bleek and Lloyd archive, a collection of mostly |xam stories, drawings, and watercolors that was assembled primarily by German philologist Wilhelm Bleek and his sister-in-law, Lucy Catherine Lloyd, in Cape Town during the 1870s. Learners and practitioners collaboratively developed a scripted and choreographed performance using props and often music.

The Clanwilliam Arts Project acknowledged the value of the Bleek and Lloyd archive for its documentation of stories and knowledges of the landscape, its fauna and flora, and the practices of |xam people. Conventional scholarship has not understood the people living in Clanwilliam today as descendants of |xam people, silencing their historical narrative. The Clanwilliam Arts Project treated the Bleek and Lloyd archive not as the horizon of what can be known about the past, but as a means that, if properly handled, can make visible anarchival strands of the past that have been erased or ignored. The project thus showed how the anarchive lives in the present, rendering it as stories that the community can leverage in order to claim ownership and rights in relation to the past. What’s more, the project engaged in anarchiving through what can be called a notography, a mode of collaborating with people that does not position them as objects of study in the past but brings into view the complex entanglements of “pre-colonial,” colonial, and postcolonial life that characterize the present.

Starting in 2017, a group of artists and cultural producers used anarchival strategies to rewrite Peru’s, and particularly Lima’s, contemporary art history. They focused on the Sala Luis Miro Quesada Garland (La Sala), a state-managed exhibition space founded in Lima in the 1980s that has showcased contemporary art for over forty years while functioning as a critical, experimental platform that often challenges state policies themselves. Recently, the state has left more and more space to elite groups in the management of the arts;22 although part of this neoliberal structure and power dynamics, La Sala has continued to respond critically to its context. In 2017, a group of independent cultural workers and artists from grassroots art/organizing initiatives started La Sala’s archive project to engage with its rich public archive. The project aimed to generate cultural infrastructure by way of an artist-led process of historical reappropriation that employed community-based organizational strategies.

The archive project transformed La Sala into an inclusive, participatory space that not only exhibited the archive and hosted related public programming but was often used as a meeting place for precarious cultural workers to discuss key issues of labor, self-organization, and poor cultural infrastructure. But a newly elected local government in 2018 denied the project access to the archive; this stalemate continues. Ever since, the cultural workers behind La Sala’s archive have confronted the paradoxes of state care and the Janus-faced quality of the state’s attitude towards the public good and the arts, which alternates between possessive care and utter disregard.23 These cultural workers, however, continued to claim their right of access. By questioning the archive’s colonial infrastructure (evident in its taxonomies and methodologies), its contribution to a unilinear historical narrative of Peruvian art, and its absences and its fundamentally unfinished condition, they claim this “not-yet archive” as an exercise in the reappropriation of public heritage and collective cocreation based on it—ultimately an exercise in institutional imagination. This anarchival reappropriation of La Sala’s archive is a fugitive practice with the potential to establish a critical platform where the country’s recent cultural history can be collectively written.24

Anarchival modes of engaging with the past remind us that the archive is not itself the past, but the result of a process of transposition and translation. It is important to be mindful of what is left out: indeed, the archive consists mainly of absences. As a strategy to grapple with these absences, anarchiving has the “capacity to make new objects available to thought,” by challenging the traditional ways in which records are categorized, organized, and accessed by mainstream institutions.25 In the process of anarchiving, it is vital to collaborate with those who are most extensively and negatively interpellated by conventional (colonial) archives. Consequently, the reconvening of archives needs to privilege the languages and everyday practices of those excluded and should answer to their needs. Developing alternative modes of dealing with colonial archives demands that we conceive of archives and their limits differently; instead of continuing to privilege the material document, we should embrace a wider spectrum of ways of relating to the past, setting our gaze on what archives constitutionally erase. This new approach can in turn help us recognize the limitations of imposed historical narratives and find ways of opening them up. Artistic practices and critical fabulations that renegotiate the distinction between reality and fiction are central to engaging the archive and writing history anarchivally.26

Art: Cross-Scale Instituting

The last strategy for creative institutionalism that we want to explore is transnational, cross-scale instituting, or what one of us has called “anticipatory representation.”27 What is the instituting potential of proliferating acts of performance, mimicry, and the mocking of traditional (inter)national art and cultural institutions? Can flexible networks with some degree of formalization take over states’ cultural functions? Nowadays, grassroots art- and culture-driven instituting often takes place on international platforms thanks to translocal, transnational networks bringing together diverse actors. They use mainstream platforms such as major biennials and the funding attached to them to consolidate and expand their institutional work. The latter is often performed on such platforms to play with the boundaries between art and reality. An example is the early Palestinian biennials, organized in the 2000s by cultural NGO Riwaq in several locations across the Mediterranean, including at the 2009 Venice Biennale. Aiming to create “a biennale within a biennale, an artwork representing an institution,” artist Khalil Rabah, then artistic director of Riwaq, staged part of the Palestinian biennial in Venice in 2009.28 Thus, in Venice the Palestinian biennial was both exhibited and implemented, creating institutional aftereffects back in Palestine. Art and institutional work came together: thanks to such generative confusion, a precarious institution such as the Palestinian biennial was made to continue and grow as an artwork presented on this key art-world platform.

Another example of consolidating smaller, precarious institutions within a large international institutional framework was OFF-Biennale Budapest at documenta fifteen in 2022. OFF-Biennale Budapest is a grassroots initiative led by cultural workers. In response to Hungary’s right-wing takeover of the state, OFF’s members have decided to self-organize outside of its art and cultural infrastructure; since 2014 they have been building an “independent” art ecosystem. After organizing three editions of the OFF-Biennale, the team was invited by ruangrupa to join the curatorial collective (lumbung) of documenta fifteen. Similar to the Palestinian biennial in Venice, the offshoot of OFF-Biennale within documenta relied on the group’s previous editions. In turn, the work done for this special OFF edition (with three projects) in Kassel laid the groundwork for the next iteration in Budapest.

Documenta’s central venue in Kassel is a neoclassical building, one of the oldest European public museums, the Fridericianum. At documenta fifteen, OFF used parts of this space as a stage for a different performative and prefigurative institution, RomaMoMA. This is a long-term collaborative project of OFF-Biennale and the European Roma Institute for Arts and Culture, involving Roma and non-Roma artists, cultural practitioners, scholars, and civil society. Traditional museums have functioned as ideological and practical tools of nation-state and imperial formation; they reinforce racialized taxonomies of value that exclude and oppress minoritarian communities. RomaMoMa both built on and built down this model. In Kassel, OFF instantiated a non- or not-existing museum, collecting and displaying the art of Europe’s largest, most oppressed transnational minority. RomaMoMa imagines, instantiates, and arguably prefigures a multi-sited museum of Roma modern and contemporary art through various iterations that manifest as exhibitions, events, and publications across time. These produce a multiplier effect: one iteration lays the groundwork for another edition to come. Through this game of instituting, OFF in Kassel simultaneously constructed and deconstructed the museum (and the international art exhibition); this non- or not-quite museum metamorphosed into a not-yet museum as both RomaMoMa and OFF-Biennale were consolidated and projected into the future.

OFF members did not act alone, but as part of a collective subject. Convened by Indonesian art collective ruangrupa, a collective of collectives created the fifteenth edition of documenta, harnessing the material, financial, and symbolic power of the (Western) art world’s most important megaevent to enable a participatory institutional laboratory. As institutions, the museum and the international art exhibition are grounded in a hegemonic exhibitionary logic that takes the nation-state for granted as the horizon and container of all meaningful activity. Ruangrupa upended this logic twice over: first by expanding an (inter)national platform for the benefit of transnational art commoning; and second by substituting an ideology of collectivization and endurance for one of individualism, authorship, ownership, and novelty. When invited to curate documenta, ruangrupa took as an institutional model the lumbung—a communal rice barn used in Indonesia to store the surplus of the harvest. In this commoning spirit, they invited like-minded collectives and organizations from many different parts of the world to share resources, both material and immaterial, and cocreate the event. Thus documenta fifteen became home to a multitude of artist collectives that were asked to continue and consolidate their existing social practice, as opposed to doing something new. As such, this edition did not simply transform a system of (inter)national hegemonic representations into one where oppressed identities were made visible and valorized; rather, practices of representation were subsumed into the cross-pollinating consolidation of commoning organizational forms.

Hack-and-mock instituting of this kind holds many promises, but also faces certain predicaments. As efforts at commoning have shown, alliances and the pooling of resources are bulwarks against unpredictability, especially for vulnerable populations. As ruangrupa pointed out, collectives must stand together with others and “must purposefully play a part in their larger contexts” in order to nurture interdependent communities.29 This instituting strategy creates spaces “where small-scale solidarity economies scale up into larger ones,” while maintaining (some of) the positive qualities of small-scale projects.30 One of these qualities is what James C. Scott’s calls metis, or practical knowledge, a kind of “acquired intelligence” that enables collectives of people to understand and respond promptly to a changing environment, from a position of closeness and familiarity.31 These institutions and their institutional ecosystems tend to be porous and responsive to discussions and needs on the ground. However, when small, informal infrastructures join forces with larger ones, such scaling-up may lead to unsustainable consequences.32 It can produce ossifying bureaucracies over time. It can also lead to a clash of scales. In the case of documenta fifteen, ruangrupa and the lumbung, mostly from former colonized locales, almost collapsed under a double burden. The German establishment gave ruangrupa the onerous task of saving a compromised Western institution, only to then attack the collective for doing its job of changing the rules of the game. Documenta fifteen was castigated and defamed by German media and politicians. While the show was still running, the German parliament held a hearing about it, where speakers discussed the limits of “artistic freedom” and called for stronger governmental control over documenta’s artistic content. Such curbing of liberties and artistic autonomy is of course a threat to the future of documenta and similar art institutions. Despite documenta’s shortcomings and challenges, however, we argue that the arduous labor of balancing conflicting scales is part of the essential task of building a solidarity ecosystem. This ecosystem—or rather, this set of overlapping, transnational ecosystems—is teeming with life. It produces innovative if imperfect cultural-political experiments that propose alternative visions for the future, while simultaneously implementing change in the here and now.

The authors would like to thank the Worlding Public Cultures project (worldingcultures.org) for supporting part of the research for this article.

Sergio Lo Gatto, “Nasce la Fondazione Teatro Valle Bene Comune: Che cosa è cambiato?” Teatro e Critica (blog), September 19, 2013 →. Our translation.

Art for UBI (Manifesto), ed. Marco Baravalle, Emanuele Braga, and Gabriella Riccio (Bruno, 2022).

Giuliana Ciancio, “When Commons Becomes Official Politics: Exploring the Relationship between Commons, Politics, and Art in Naples,” in Commonism: A New Aesthetics of the Real, ed. N. Dockx and P. Gelien (Valiz, 2018), 281.

Art for UBI (Manifesto), 138 →.

Lauren Berlant, On the Inconvenience of Other People (Duke University Press, 2022), 80, 82. See also L. Berlant, “The Commons: Infrastructures for Troubling Times,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 34, no. 3 (2016).

Hanan Toukan. The Politics of Art: Dissent and Cultural Diplomacy in Lebanon, Palestine, and Jordan (Stanford University Press, 2021); Chiara De Cesari, Heritage and the Cultural Struggle for Palestine (Stanford University Press, 2019).

Nuraini Juliastuti, “Commons People: Managing Music and Culture in Contemporary Yogyakarta” (PhD diss., Leiden University, 2019).

Melani Budianta, “The Blessed Tragedy: The Making of Women’s Activism During the Reformasi Years,” in Challenging Authoritarian Rule in Southeast Asia, ed. A. Heryanto and S. K. Mandal (Routledge, 2003).

Juliastuti, “Commons People,” 154.

Tricia Hersey, Rest Is Resistance: A Manifesto (Hachette, 2002).

Patrick Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (2006).

Davina Cooper, Feeling Like a State: Desire, Denial, and the Recasting of Authority (Duke University Press, 2019).

Zoom interview with Commune member, December 2022.

Zoom interview with Commune member, December 2022.

Elke Kaschl, Dance and Authenticity in Israel and Palestine: Performing the Nation (Brill, 2003); Nicholas Rowe, “Dance and Political Credibility: The Appropriation of Dabkeh by Zionism, Pan-Arabism, and Palestinian Nationalism,” Middle East Journal 65, no. 3 (2011).

Nasser Abufarha, The Making of a Human Bomb: An Ethnography of Palestinian Resistance (Duke University Press, 2019).

Noura Alkhalili, “Enclosures from Below: The Mushaa’ in Contemporary Palestine,” Antipode 49, no. 5 (2017); Raja Khalidi and Sobhi Samour, “Neoliberalism as Liberation: The Statehood Program and the Remaking of the Palestinian National Movement,” Journal of Palestine Studies 40, no. 2 (2011).

De Cesari, Heritage and the Cultural Struggle for Palestine, esp. 40.

Filipa César, “Meteorisations: Reading Amílcar Cabral’s Agronomy of Liberation,” Third Text 32, no. 2–3 (2018).

Carine Zaayman, Anarchival Practices: The Clanwilliam Arts Project as Re-imagining Custodianship of the Past (ICI Berlin Press, 2023).

Ana Laura Stoler, Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense (Princeton University Press, 2009).

Giuliana Borea, Configuring the New Lima Art Scene: An Anthropological Analysis of Contemporary Art in Latin America (Routledge, 2021).

João Biehl, Vita: Life in a Zone of Social Abandonment (University of California Press, 2013).

Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study (Minor Compositions, 2013).

Ana Laura Stoler, “On Archiving as Dissensus,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 38, no 1 (2018): 46.

For critical fabulations, see Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008).

De Cesari, Heritage and the Cultural Struggle for Palestine.

De Cesari, Heritage and the Cultural Struggle for Palestine.

ruangrupa and Artistic Team, documenta fifteen Handbook (Hatje Cantz, 2022), 12.

Mary N. Taylor and Janet Sarbanes, “From Islands of Commons to Collective Autonomy,” e-flux journal, no. 136 (May 2023) →.

James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State (Yale University Press, 1998), esp. 313ff.

ruangrupa and Artistic Team, documenta fifteen Handbook, 40.