From Kenneth S. Kendler, Rodrigo A. Muñoz, and George Murphy, “The Development of the Feighner Criteria: A Historical Perspective,” American Journal of Psychiatry 167, no. 2 (2010).

This essay is part of an e-flux Notes series called “The Contemporary Clinic,” where psychoanalysts from around the world are asked to comment on the kinds of symptoms and therapeutic challenges that present themselves in their practices. What are the pathologies of today’s clinic? How are these intertwined with politics, economy, and culture? And how is psychoanalysis reacting to the new circumstances?

***

The place of psychoanalysis in the field of mental health is a topic that has unfortunately been more muddled by attempts to answer it than if the question had been avoided altogether. For comparing psychoanalysis to therapy or psychiatry can lead to a series of assumptions that are difficult to correct: for instance, assuming that psychoanalysis and psychotherapies share the same clinical object, that psychoanalysis is merely a form of therapy meant to cure mental disorders, that other therapeutic practices are legitimate and scientifically proven interventions to restore normalcy, or that modern psychiatry’s concept of abnormality is accurate. Therefore, the question we should be asking is not “what kind of therapy is psychoanalysis?” but rather, “what is psychotherapy originally a therapy of, and how does psychoanalysis differentiate itself from it?”

That different therapies were produced more or less simultaneously by science to cater to various subjective difficulties is a common misconception. In reality, most of these methods conflict with each other and claim to cure the same symptoms, each claiming to be more effective than the others. And although evidence-based research has retrospectively categorized some of these therapies according to their measurable effectiveness, none of them has had its core beliefs and principles refuted by any of the others at any point in time.1 In fact, the differences between these therapies are not only due to the fact that they were meant to serve different patients at their inception, but they also view the same patients differently according to their philosophical and discursive commitments. Despite being backed by empirical evidence, what these therapies take as measurable facts remains a product of their concepts, notions, and philosophies of human subjectivity. That is to say, what psychologies end up measuring always remains bound to the politics they depart from. This does not mean that therapies do not work towards their objectives, but that their objectives are, as such, symptoms of their discourse.

Moreover, each therapeutic method first served as a new approach to treating the uncured with preexisting therapies; hence they all aimed to make waves against the ruling discourse of their time by offering novel conceptions of suffering and well-being.2 In short, the differences between therapies are not just technical but mostly political and philosophical. For if one sticks to the technical aspect, the number of therapies currently available to treat any given mental condition indicates the discontent by which their proliferation has been driven.

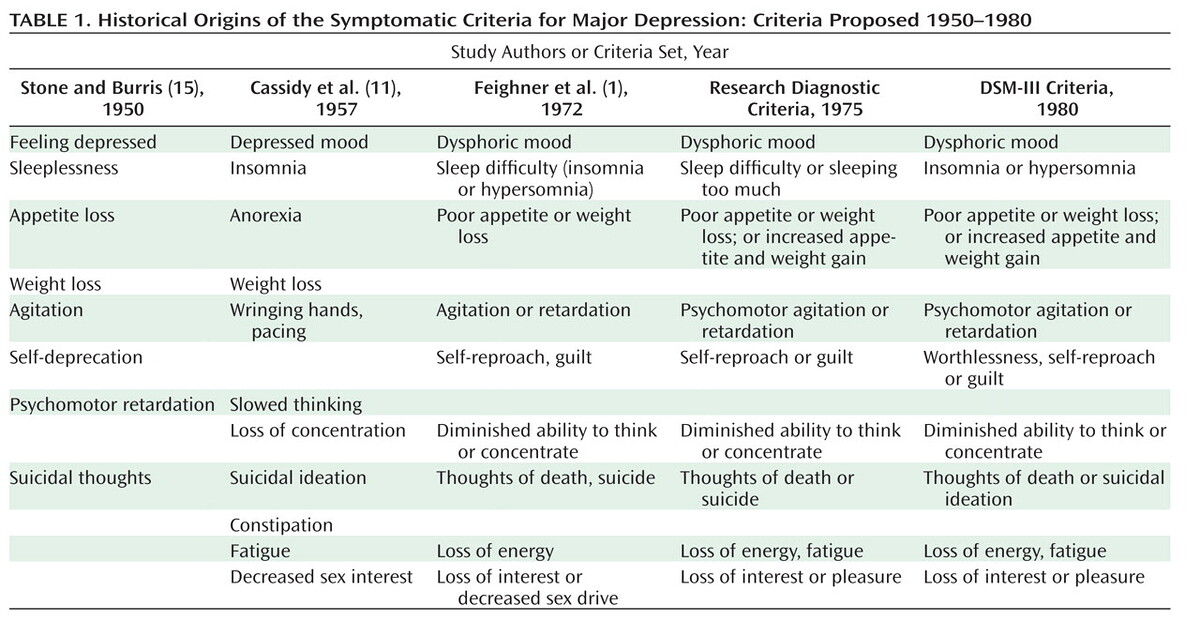

Instead of questioning the concept of normality that each therapy vows to reinstate, the whole matter has been dismissed with the advent of evidence-based psychiatric research, which compartmentalizes therapies according to their effectiveness against symptoms, giving them technical legitimacy at the price of negating the field of debate over the definition of subjectivity. This came along with psychiatry’s revolt against its initial reliance on the structural categories of Freudian psychoanalysis (such as neurosis, psychosis, and perversion, along with their subcategories),3 through the adoption of evidence-based research between the 1950s and 1970s. This transition may be seen in the development of the Feighner Criteria and the third edition of the DSM in 1980. American psychiatry made a substantial effort to reduce the conception of previous diagnoses to observable physical and behavioral characteristics, aiming to establish an “objective” clinical categorization that would standardize clinical observations and rule over their singularity.4

Following this historical moment, diagnostic categories became more focused on descriptive and measurable symptoms, which benefited pharmacological experiments. However, these categories lost their conceptual and etiological foundations. In fact, the DSM-III significantly increased the number of clinical syndromes isolated in Axis I, “many of which are based on splitting old categories into multiples,”5 while the number of personality and developmental disorders isolated in Axis II remained almost the same.6 The novelty of the DSM-III was the separation of observable clinical syndromes from structures previously attested to by personality disorders. It posed symptoms as stand-alone pathologies that are curable on their own, dissociating them from their subjective significance.

While it is undeniable that the diagnostic revolution has benefited a large population of patients by refining psychotropics and eliminating many symptoms, it has also converted the subject into a patient who believes their struggles are merely symptoms to be eradicated. By assigning a diagnosis and educating the patient about it, psychiatry offers them a prognosis to aim for—namely, the annulment of what has been identified as a syndrome or disorder. In essence, psychiatry has fostered a collective rejection of the intricacy of the subject’s relationship with the Other that underlies these symptoms, thereby creating an additional personality disorder that is formally advertised as ideal normality by diagnostic manuals and anti-stigma campaigns: the personality devoid of disorder, which is mostly visible in popular images of quasi-autistic self-control and self-fulfillment.

The crucial issue at stake is not the efficacy of the treatments that have arisen from the modern diagnostic system, but the significant efforts that have been made to separate symptoms from personality disorders, which are essentially disorders of one’s relation to the Other. Since the release of the DSM-III, personality disorders have remained virtually unchanged; “stability … appears to be the hallmark of the last three versions of the DSM, in that 11 personality disorders have remained essentially unchanged across the last three versions.”7 Furthermore, these unchanged categories are the ones where pharmacological treatments have been least effective, to the point where psychiatry has had to adopt a range of case-management approaches in place of its traditional curative stance. In this regard, modern psychiatry has formed alliances with various therapeutic schools, which have expanded its framework without addressing its discursive gap—agreeing to treat the relation to the Other as a symptom, rather than addressing the symptom as the subject’s attempt to regulate his relation to the Other.

Thus, the modern diagnostic categories of psychiatry not only dissociated patients’ symptoms from the hurdle of their relation to the Other; they also commanded this dissociation and provided the cultural means to sustain it. For example, the denunciation of authority in the hysteric’s discourse was reduced to the traumatic event of post-traumatic stress disorder; or the problem of the Other’s demand was converted into the intrusive thoughts of obsessive-compulsive disorder. In short, the unfolding of modern diagnostic categories extracted whatever it could out of the problem of transference (whereby psychiatry and therapy’s stature of curative scientific techniques is enabled) and dumped the rest into personality disorders.

Let us now shift our focus to another crucial aspect: the shared methodological approach between psychiatry and therapy. Both assume that a single diagnosis can adequately explain a person’s suffering and provide guidance for treatment. This implies that the diagnosis is not intended as a treatment in itself, but rather as a means of gaining knowledge about the patient’s “reality” in order to inform subsequent action. But what if this “reality” was itself an action against knowledge? What if mental-health practices had diagnosed as a disorder the subject’s attempt to amend, by some disorder, a prior diagnosis? In fact, what the patient struggles with, even before getting diagnosed by a practitioner, is a whole diagnostic enterprise running within him, a discourse that reduces him to a formation or category that turns the impossibility of his enjoyment into impotence, by positivizing it on the Other’s end through some ideal of normalcy. In other words, a diagnosis formulates the order given by discourse (to enjoy), by omitting the inconsistency of the enjoyment it commands, which is the Other’s inconsistency. One finds in every diagnosis an inherent defense of the order of knowledge against the Real, recasting the Other’s inconsistency as the subject’s incapacity to enjoy. The question psychoanalysis poses to psychiatry (or therapy) can thus be formulated as follows: Is it suffering that necessitates a diagnosis, or is it the diagnosis that requires suffering?

The condition that psychoanalysis initially defined as neurosis, and which it adopted as its original object, is precisely not a diagnosed mental disorder but a structure of the subject’s relation to the Other, which is generative of “normalcy” as much as disorders. Therefore, the disagreement between psychoanalysis and psychiatry goes beyond the issue of diagnostic categories; it lies at the level of the nature and function of diagnosis itself. Psychoanalysis introduced into this debate, long before the modern revision of psychiatry and psychology, a mode of action that is fundamentally distinct from diagnosis: interpretation. Interpretation differs from diagnosis not only in how it operates on the subject, but also in being opposed to it.

For example, consider the rule of free association in psychoanalysis. Although asking an analysand to associate freely is of no practical use, since the associations that are made are still diagnostic in nature, what is interpreted during the course of the investigation is not what the analysand’s discourse intends to diagnose, but the very discourse that diagnoses. In fact, Freud’s rule of free association is more concerned with the analyst than with the analysand. The analyst can only function as an analyst by listening to the analysand’s self-diagnoses as a free association. Instead of becoming involved in the analysand’s diagnostic process, the analyst is meant to interpret it. This position is in stark contrast to that of therapy or psychiatry.

In order to revive the debate with psychiatry and psychotherapy, the psychoanalyst should be understood as starting from the idea that the complaints that analysands present are not about their failure to conform to the norms of the “normal,” but rather their failure to effectively negate them. Psychoanalysis does not summon the subject’s complaint as a wish to reinstate a previous condition of health and happiness; rather, it hears in it the urge to cut through and amend the discourse that sustains this very complaint.

“The most rudimentary tenets of CBT, for example, have been comprehensively refuted by the neuroscientific work of Damasio and LeDoux well over a decade ago (i.e. there is no functional or neuroanatomical basis for the infamous affect-intellect distinction), but this does not stop official psychology from proclaiming CBT as ‘evidence based,’ or from regulatory bodies enforcing this doctrine. With no recourse to the tools of the humanities—conceptualizing, critiquing, historicizing—there is little way out for psychology as a discipline other than to continue as it is, short of a veritable scientific revolution.” David Ferraro, “Psychoanalysis and the DSM: A Brief Discussion and Critique,” presentation at a meeting of the Lacan Circle of Melbourne, July, 2013 →.

“In the 1950s, general systems theory, viewed by many as a ‘revolution in scientific thought,’ was integrated into the newly emerging practice of family therapy. This systemic theoretical approach became increasingly popular in the 1970s and 1980s, when it was pronounced the fourth force in the field. L’Abate explained that, in the middle of the 20th century, psychotherapists were unprepared to work with families, even though family life and relationships are critical to human existence and well-being. He emphasized the significant clinical difference between the linear focus on an individual and a ‘circular, contextual, and dialectical’ focus on families. In 1998, Becvar and Becvar proposed that second-order cybernetic systems theory, particularly as applied to family therapy, represented a paradigm shift in the field of psychology and psychiatry. Unlike previous paradigms, this approach provided a postmodern understanding of humans who live in their own social and cultural constructions that are co-created and shared with others, systemically through mutual interaction. By the end of the century, systemic relationship therapy had become mainstream, with its own international professional identity, journals, societies, state licensure, and university curricula.” Colette Fleuridas and Drew Krafcik, “Beyond Four Forces: The Evolution of Psychotherapy,” SAGE Open 9, no. 1 (2019) →.

“In the 1940s, as a result of several historical processes, Freudian psychoanalytic theory and practice came to dominate American psychiatry. By the mid-1950s, nearly every department chairman of psychiatry in the United States was an advocate of psychoanalysis. In the higher-prestige residency training programs, trainees were typically expected to undergo a personal psychoanalysis as a part of their training.” Kenneth S. Kendler, Rodrigo A. Muñoz, and George Murphy, “The Development of the Feighner Criteria: A Historical Perspective,” American Journal of Psychiatry 167, no. 2 (2010) →.

Kendler et al., “Development of the Feighner Criteria.”

Ferraro, “Psychoanalysis and the DSM.

“Overall, the DSM-III listed 11 specific personality disorders (compared to 12 in DSM-I and 10 in DSM-II ). Only four personality disorders remained essentially unchanged from DSM-I through DSM-III: paranoid, schizoid, antisocial, and passive-aggressive types. Two had name changes, each containing a touch of irony: The new DSM-III histrionic personality disorder was formerly the hysterical personality disorder in DSM-II, although the name histrionic personality disorder appeared in parentheses in DSM-II. Also, the DSM-I compulsive personality disorder, which changed to obsessive compulsive personality disorder in DSM-II, changed backed to its original name in DSM-III, compulsive personality disorder.” Frederick L. Coolidge and Daniel L. Segal, “Evolution of Personality Disorder Diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,” Clinical Psychology Review 18, no. 5 (1998).

Coolidge and Segal, “Evolution of Personality Disorder Diagnosis.”