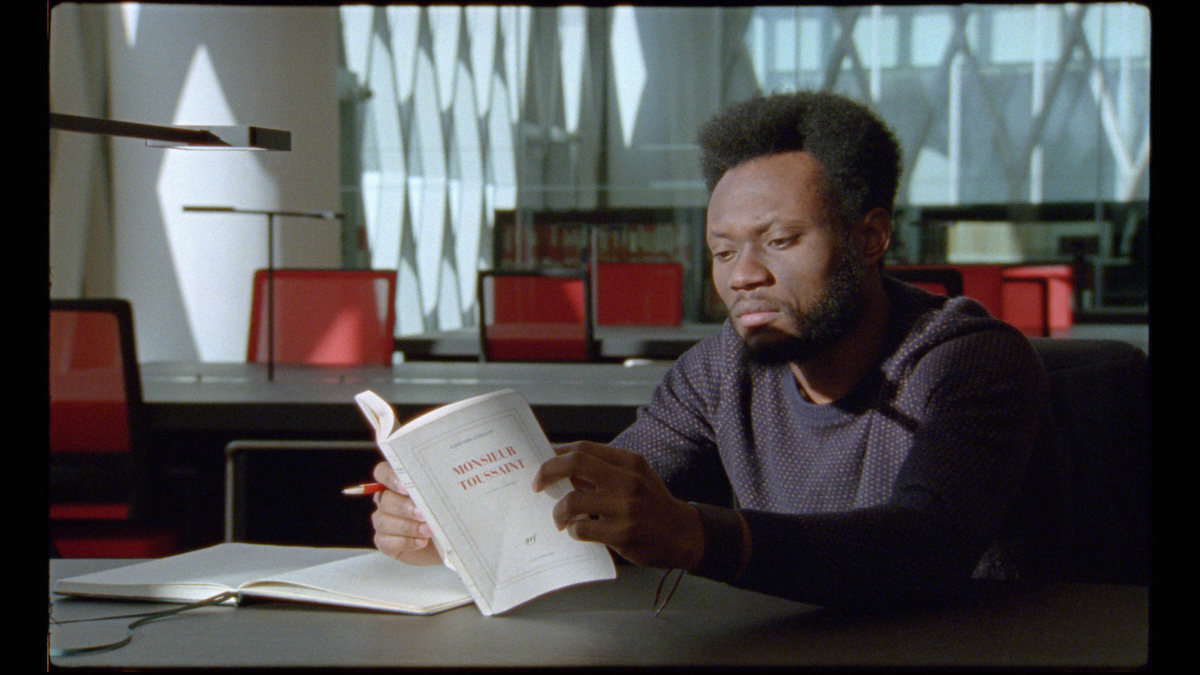

Film still from Ouvertures, directed by Louis Henderson and Olivier Marboeuf, 2020.

This dialogue is published on the occasion of a screening of Ouvertures (2020) at e-flux Screening Room on May 6, 2023. The film, directed by Louis Henderson in collaboration with the Living and the Dead Ensemble, is a visual and sonic exploration of the history of Haiti and a captivating attempt to bring the Haitian revolutionary Toussaint Louverture back to life. A longer version of this dialogue was published in Tell It to the Stones: Encounters with the Films of Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub, edited by Annett Busch and Tobias Hering (Sternberg Press, 2021).

***

Annett Busch (AB): Let’s start with beginnings, the idea of beginnings, with affinities, with Jacques Rivette. In one of our first conversations1 you mentioned Out 1: Noli Me Tangere2 (1971) as a starting point, a source of inspiration, to think about the play Monsieur Toussaint by Édouard Glissant. Which made me curious and triggered a range of associations: How to go from Rivette to Glissant via Straub and Huillet? How and what do you see, read, and hear to make these connections? How did the process of decision-making evolve and how do these influences transform into your own approach to filmmaking? Can you recall that idea-giving moment, before the actual working process, that later became Ouvertures?3

Louis Henderson (LH): I first saw Out 1: Noli Me Tangere at the BFI during the Rivette retrospective in London in April 2006. There was a small crowd of committed people that came to the cinema over three days and collectively worked through the twelve-and-a-half hours of the film. That experience had a profound impact on me in various ways. I was particularly taken with the way in which Rivette treats acting, improvisation, and direction. At that time I was studying film and video at London College of Communication, and I had started to develop a (continued) problem with the idea of directing action, of directing people in general. What interested me about Out 1 was how Rivette creates a space for the actors to unfold their characters on their own terms, how he allows for the actors within that space to be active agents in the development of the mise-en-scène, and how this engages a kind of improvised choreography with the camera, the streets they are shooting in, and the passersby that happen to be included in scenes. The idea of playing became important for me, especially when thinking about adapting a piece of theater for cinema, and how to play this game of improvisation between us all as a dialogue, as a process. Here I am reminded of an interview with Rivette about Out 1 that appeared in La Nouvelle Critique. The interviewers ask him what the film is about, and he answers: “To begin with, play in all senses of the word was the only idea: the playing by the actors, the play between the characters, play in the sense that children play, and also play in the sense that there is play between the parties at an assembly.”4

AB: “Improvisation” seems to be an explosive concept to start with, full of traps and misunderstandings. What also resonates with that term is something like an ultimate contradiction to what the filmmaking of Huillet and Straub stands for—which is probably not what you’re alluding to. We know from jazz musicians that the moments of “free play,” of improvisation, can only happen within a strictly framed constellation. Jean-Marie repeatedly recalled a similar, dialectical relationship: to set up a strong and very well prepared frame in order to allow something unpredictable to happen. “I don’t blow it up; I wait until reality does it. Or I work in opposition to the whole. And the air and the light and so on, the sounds and such––the film begins to live in all that isn’t foreseen. But only because of the frame-work, otherwise there wouldn’t be anything unforeseen.”5

Or, to put it differently: How to create a setup that is in itself research, that allows something new to happen in front of the camera, something that exceeds or contradicts what the director is expecting, that goes beyond intentions? “Improvisation” unfolds in response to something, a challenge, a problem, a constellation. What are the given elements, the tools to play with? What is given in Out 1, in various ways, are texts. In almost every sequence we see printed matter. We don’t experience text as a story to serve as a script to be learned and rehearsed before the shooting starts, and then acted out in front of the camera as if the story were real. Written and printed text, books or slips of paper, remain a kind of character leading to an interplay. We see people “dealing” with texts, struggling with their meaning, their authority.

Your starting point is the play by Glissant that led you to Haiti. Can you describe how you came across his play Monsieur Toussaint? Why was it important? What did the play do?

LH: The film Ouvertures begins with images of a researcher reading Louverture’s handwritten letters in the National Archives in Saint-Denis as we hear how he wrote these letters up until his death, imprisoned by Napoleon in the Château de Joux in the Jura Mountains. Those letters contain evidence of a once-enslaved person who had learned to read and write, battling with the French language mixed with the as-yet-unofficial language of Haitian Creole, in order to claim his innocence and demand once again his freedom from Napoleon. From the very beginning of the film, written and spoken language become the means through which a struggle with authority is both put into place and made possible.

Then as the narrative proceeds, the premise of the film is in fact a struggle with a text by Glissant, the struggle to find a way to voice and perform Glissant’s Monsieur Toussaint in Haiti in 2017. The problem arose from the fact that Glissant wrote the play in French, and generally there is an issue with the continued authority that French has in Haiti, as the language of an upper-class elite that suppresses Haitian Creole. This power dynamic contains within it remnants from the afterlife of slavery in Haiti, as French was the language of the ex-colonizers, slavers, and plantation owners. However, this is very nuanced and complicated in Haiti, as the majority of people do not speak or read French, yet the first constitution of independence, convoked in 1801 by Toussaint Louverture, was written in French, and it was the language of the political rulers during and after the revolution. So for us it became a struggle with how to appropriate and reconfigure the inherent violence of the French language (within Haiti specifically) through a translation of a work by Glissant into Haitian Creole—the language of a people that organized the only successful slave revolt in history, abolished French slavery, and created the first free Black state in the Americas.

In addition, the whole project has a trajectory very much related to books. In 2013 I was in Ghana trying to make a film that spoke about Ghana’s independence from British colonial rule in relation to certain animist practices. Towards the end of my time in Ghana I went to the George Padmore Research Library in Accra on various occasions. There I found a copy of The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution by C. L. R. James, and was immediately taken with James’s descriptions of the famous night of Vodou ritual in Bois Caïman of August 28, 1791, which started the Haitian Revolution. Later, after reading the book, I found it particularly interesting that James had written The Black Jacobins in 1938 as a historical account of the Haitian Revolution so as to imagine a future of independence on the African continent.

This encounter with C. L. R. James in the George Padmore Library in Accra was the beginning of my interest in the history of Haiti, and the impetus for making a film. In the summer of 2013 I started writing a treatment for a ghost film set in the Jura Mountains, where Louverture had died. The film would then travel across the Atlantic, back the other way, with the ghost of Toussaint Louverture returning to his native land after more than two hundred years of exile. Finally in Haiti he would discover a group of actors rehearsing C. L. R. James’s play Toussaint Louverture: The Story of the Only Successful Slave Revolt in History, which was performed once in London in 1936, and whose manuscript was found again in 2005 after previously thought to be lost. Then I received Édouard Glissant’s Monsieur Toussaint as a gift from a friend in the winter of 2013 and started to think that this book could become the source material for the rehearsals in Haiti rather than the play by James for various reasons, notably because Glissant sets his play in a prison cell in the Jura.

AB: Before we continue following the traces of Glissant and C. L. R. James, I would like to stay with the idea of beginnings and influences. Besides Rivette you mentioned Huillet and Straub. When and where did you come across their work and how were these films important for you? You seem to have developed a pretty good strategy to process influences in a way that they shape your movies, and at the same time they are hardly visible.

LH: The films of Straub and Huillet were introduced to me initially through a screening of Une Visite au Louvre at the Tate Modern in London as part of a Pedro Costa retrospective in 2009. Since then I have been fascinated with the idea of cinema as a form of archaeology, and how this entails a kind of cinematographic stratigraphy, or the writing, imaging, and sounding of layers through a vertical montage. Certain of their films excited me very much, such as Cézanne; Fortini/Cani; Dalla nube alla resistenza; Toute révolution est un coup de dès; Trop tôt/Trop tard; and Geschichtsunterricht—all films that deal with how history can be brought alive in the present, from books and archives into landscape and voice. And then there is this connection between literature and geology, which is to say that stratigraphy is primarily a literary form—stratigraphy, the writing of strata. When thinking about stratigraphy in cinema, my questions were always: How can we read what is written in this strata? How can we hear the voices that are silenced in strata?

The idea of burial is important for Straub/Huillet I think—the burial site as a way to make a monument of landscape, a marking of death against forgetting within the land, so that people can be remembered posthumously. Post-humus—a Late Latin spelling that added an H to postumus so that the idea of earth and burial becomes present within a word that already indicated something existing after death. Yet in the case of my interest with Louverture, the fact remains that he never had a real burial in French soil. His bones were thrown into an unmarked grave for prisoners, which was dug up later when fortifications were being made for the Chateau de Joux. Over these last few years I learned that for many Haitians, if someone as important as Louverture does not receive a proper burial he will continue to haunt the earth. When visiting Louverture’s former prison cell in the Jura for the first time, I was troubled by the lack of a grave and went looking for his presence within the surrounding landscape. The Jura was once a tropical ocean that disappeared and left behind many layers of stratified limestone. Walking within that landscape you can see how it was created, and the fossilized remains of that tropical ocean exist today. In the tradition of Haitian Vodou, when people die their souls go “beneath the waters.” I started to think that perhaps Louverture’s ghost might be fossilized within this ocean-mountain landscape. His bones were ossified into France and thus his soul must still haunt the countryside of the Jura.

Before his death Louverture wrote profusely from his prison cell, so much so that Napoleon banned him from writing. Yet in an act of defiance Louverture continued to write and would hide his letters in a scarf wrapped around his head. After his death these letters were found and eventually ended up in the French National Archives in Saint-Denis. In 2013 I went to the archives to read Louverture’s handwritten memoirs, and then went to find the place in which they were written. Of course when I arrived in the Jura there was really nothing to be found of Toussaint Louverture. All that was left was the landscape in which he wrote his letters. In Ouvertures the first act shows these landscapes in a series of sequences in which we see the limestone strata that make up this territory of France, and we hear a voice narrate Louverture’s words on the revolutionary ideals of liberty and equality and the importance of “uprooting the tree of slavery” in the French territories overseas.

AB: London 1936. We can imagine the city as a condenser, a catapult, a crossroad—to get an idea of what’s “in the air,” of what makes it, in the end, possible for you to find a book in 2013 in a library in Accra named after the theorist, adviser, organizer, and writer George Padmore, born in Trinidad, like C. L. R. James. At the time, Amy Ashwood Garvey had just opened the International Afro Restaurant at Oxford Street, which became something like a hub for Black intellectuals, writers, entrepreneurs, artists, journalists, lawyers, and future presidents, where Padmore, James, Kwame Nkrumah, Jomo Kenyatta, Claudia Jones, Una Marson, Ras Makonnen, and many others sat together, debating, plotting, probably laughing, arguing. James’s play, Toussaint L’Ouverture, was staged in London’s Westminster Theatre—right in the governmental center, not in some off-theater—with Paul Robeson, a star actor and activist, in the role of Toussaint L’Ouverture. From James’s biographer Anna Grimshaw we can learn that “it was planned as an intervention in the debates surrounding the Ethiopian crisis.”6 The invasion of Ethiopia by the Italians had an important mobilizing, politicizing impact for many. It was crucial for somebody like James to see and articulate these connections between the historic, exemplary revolt in Haiti and a future struggle for independence in the African countries. A year later, Padmore and James cofounded the International African Service Bureau.

LH: James’s thoughts about the connections between historic revolt and future African independence are something that he directly addresses in both the foreword (to the 1980 edition) and the end pages of The Black Jacobins. In the 1980 foreword he mentions how his book had been of important political use for “some Pan-African young men from South Africa” that he had met during celebrations for the independence of Ghana in 1957.7 In the last two pages he makes his intentions with the book very clear: “Finally those black Haitian laborers and the Mulattoes have given us an example to study.” And then the penultimate line reads: “The African faces a long and difficult road and he will need guidance.”8

This method of historical speculation is something that Glissant uses and has written about in relation to his own work. For example, in the preface to the 1961 edition of Monsieur Toussaint, Glissant’s first sentence mentions The Black Jacobins and then a paragraph later he says of his own play: “The work … refers rather to what I would call, by paradox, a prophetic vision of the past.”9 This appeared to me to show some sort of lineage with what James had been trying to do with The Black Jacobins and what Glissant then tries to do with his own work on Toussaint Louverture. I became increasingly interested in working with Monsieur Toussaint, initially because Glissant’s play is set in Louverture’s prison cell in the Jura Mountains, a place I had been visiting and a landscape I was becoming interested in, but also because Haiti is represented through memory and the haunting of ghosts in the present, a particular attitude towards death that had intrigued me for some time and had already formed the basis of nearly all of my earlier films. Then something else became apparent and eventually important: in the avertissement to the 1978 edition of Monsieur Toussaint, Glissant writes about the (French) language of the play: “I tried, however, to resist a simple mechanism of creolization, the artifice of which was quite obvious. The mise-en-scène of this story can choose its own linguistic environment; and the Creole language is sufficiently free in its written non-fixity for the director and actors to come together and complete, through improvisation, the intentions of the author.”10

This seemed like a challenge perhaps—indeed, why were certain characters like Mackandal, a maroon from the eighteenth century, speaking to Louverture in Glissantian French? When in Haiti in 2016 I spoke of this very matter to a friend of mine—the slam poet and actor Rossi Jacques Casimir—he said that if I wanted to work on the play in Haiti, we would have to translate it to Haitian Creole as a practical but also political imperative. This was not simply a question of adapting the play from one language to another, but also from 1961 to 2016, as we thought it was important to transform the words of the play with the contemporary slang particular to the actors’ lives and situations, essentially creolizing Glissant’s play.

AB: That’s a series of interesting shifts. With the two very different, both non-Haitian authors also comes a move from the anglophone to a francophone Caribbean perspective (C. L. R. James, born 1901 in Trinidad; Édouard Glissant, born 1928 in Martinique). James, at the time connected to the Trotskyist movement, sets his piece in the middle of action, crisis, and decision-making; he is using the stage to play through the role of revolutionary leadership in relation to a people, while Glissant begins and unfolds his play when this action-driven battle has been lost for Louverture, sitting in a prison cell. What he can still do is to write, secretly, while the battle continues for the people in Haiti. You mention the importance of language, of vernacular language, which also means to draw the attention towards the people, how they speak, and how they think and act in very different ways. A shift that is quite fundamental, and raises the question of leadership in a very different way. It’s more a distribution of various responsibilities and roles. Translated into the language of performance, theater, and then also film, “improvisation” could mean not to respond unprepared, but to re-act in ways that were not anticipated by the director, to capture a kind of collective, polyvocal momentum.

LH: For a few years I have been engaged in a conversation with the French writer and producer Olivier Marboeuf about the necessity to dissipate the individual and often narcissistic voice of the artist within an artwork. To find new ways of making films that fight against the insistence of a certain capitalistic impulse in cinema and art towards the celebration of the singular voice and point of view. In many ways this is connected to a shift away from heroism towards collective action, and this is what both Glissant and James attempted to show with their respective works about Haiti. In the case of Monsieur Toussaint we have a hero on his deathbed confronted with various voices from Haiti’s past, haunting and taunting him, revealing his individualistic ambitions to become governor. In the introduction to the play, Glissant develops James’s and Aimé Césaire’s respective theses that Louverture had to allow himself to be taken by Napoleon’s forces, that he had to sacrifice his life and his position of power in order for the revolution to achieve its purpose for the collective good. Furthermore, in Le Discours Antillais (1981), Glissant wrote of the importance of writing “the novel of the We,” by which he meant a novel that experiments with a polyvocal narrative as an expression of a collective We.11 Glissant conceives this as a way towards imagining a postcolonial Caribbean society that is brought together through difference and not fragmented through nationalism. This was and still is an idea that interests us greatly, and so we started working together to understand how to make films as collective conversations, as study sessions, as workshops. Films that could be discursive objects opening up an array of activities at the edges of the project itself.12 Around this time we discussed the possibility of turning the treatment I had written about the ghost of Toussaint Louverture into a collective project that could incorporate the choral voice of a We.13

Monsieur Toussaint thus became the starting point from which we tried to bring a chorus together. We translated the play from French to Haitian Creole and then put on the play as a one-off performance in the cemetery of Port-au-Prince in December 2017. The play was very important for the project, as a way to create something that didn’t exist yet—this was the theater group we formed in 2017, the Living and the Dead Ensemble. Our initial impulse to create the group came from the shared desire to find a multivocal and choral method of authoring a work. Furthermore, I was interested in trying to incorporate methods of free improvisation (in the musical sense) into the film, and so we set up the theater group and put on the play (which eventually took on an existence of its own) and then filmed it as it gradually unfolded, the action becoming increasingly fictionalized as the film progressed. This was the basis of the process—to create a situation that was entirely pre-considered and constructed, based on fiction, and then allow for life to intervene within that space and to bring with it a type of reality that we would never be able to imagine. Much like you describe above, improvisation can only come when there is a clearly defined space to work within. These are the boundaries that are necessary in order for people to move freely. When I speak about mise-en-scène, this is what I mean; it’s constituted by the situations that we created through research and work, and this then allows for the film to live in what is unforeseen, as Straub says. It was a question of trying to make a film through dialogue with people from Haiti rather than going to Haiti and imposing a story onto a landscape and people.14

AB: One of the most powerful moments in the third part of Ouvertures is the long conversation between Léonard Jean-Baptise (Léo) and Zakh Turin while they are walking in the outskirts of Port-au-Prince. The conversation evolves from the question of belonging, of being “a citizen of the world.” There is an unresolved intensity within their dialogue and I keep wondering what happened to make it possible. It sounds and looks like a perfect example of non-scripted dialogue within a completely scripted frame, an estranged familiarity—and familiarity understood as a feeling that is produced by endless repetition put under pressure (estranged) through the presence of the camera.

If I make a link here to Huillet and Straub, what comes to mind is the intense presence of the actors in Operai, Contadini (2000). The actors hardly move physically; they just stand at a particular place in the woods, reading from a sheet of paper, static in a way that nothing unpredicted can happen, so it seems. Most people would call this utterly boring. Over time you realize that the actors are not professional actors. They are probably peasants and workers and the story they are reading might be familiar to them. Their bodies and minds inhabit an experience that becomes present on screen, and the way this happens is unpredictable and not under the control of the directors. It’s a result of hard work with text and the act of speaking, to let something appear that exceeds the intention of the directors and the actors.

What I am trying to emphasize by putting these two sequences next to each other are possible similarities rather than a difference—beyond the quite different circumstances and starting points. What also comes into play in relation to creating the frame, of course, are the means and circumstances of production.

LH: Shooting with a small digital camera and only one or two people doing sound means that we have a very small technical presence in the space we are shooting in. Our crew was always much smaller than the situations we were trying to film. What was around our frame was always much larger than what we were trying to contain in the frame, such as the rara sequence at the end of the film, when we had an entire rara band, a huge amount of extras, a storm and the night approaching, the ocean, the full moon, the sunset, and also eight actors. Because of the unfathomable nature of what is outside our frame, we can only allow for the unforeseen to start to take place within the frame. In these instances we can allow the camera to run for hours, but we always need a well-organized rhythm section to keep us in order.

Regarding the conversation about being a “citizen of the world,” this was a topic that had come up in various conversations with the group. It was often presented by Léo, as he thinks of himself as a citizen of the world rather than simply a Haitian citizen determined by preexisting sociocultural constructs. We often felt that Léo represented a kind of Glissantian figure in this regard, the later Glissant from after Poétique de la Rélation in which he has abandoned the national specificity of Martiniquan politics and proposes his totalizing concepts of rélation and Tout-monde. And Zakh, as an avid reader of both Frantz Fanon and Aimé Césaire, seemed to represent a position more in line with the négritude and Caribbean autonomy of the earlier Glissant. Neither of them had had this conversation beforehand, however; nor had we really discussed the scene at all. All we had decided was to shoot a scene where the character of Toussaint is finally walking with the group in an area of Port-au-Prince called Pont Rouge, the place where Jean-Jacques Desslines was assassinated in October 1806. The first part of the scene was based on a loose script where Léo expresses his interest in the notion of being a “citizen of the world” to Toussaint, whom we often discuss in the group as being the first diasporic Haitian. After we shot this scene I had the idea that Léo, while ambling around, could run into Zakh, who would take issue with him on what he had just said to Toussaint about world citizenship. Even if this might seem like an ad-hoc decision taken within the moment, it was in fact based on the knowledge we all had of each other from spending considerable time together and conversing on a wide array of subjects. Léo was completely unprepared for what Zakh said to him, and so the conversation in this scene unfolded as we filmed everything in one take that lasted about twenty minutes. In this instance, as with many others in the film, the frame is organized according to the location, the time of day, the amount of light we have left to shoot with, the choice of people talking, and the subject loosely decided beforehand. Then within that frame the actors are free to decide upon which part of their narrative they will convey, and that is perhaps where the element of free improvisation comes in.

AB: You mentioned above your interest in strata, how history and time materializes in the landscape and how to make these layers “speak.” For the first part of Ouvertures you were filming with a 16 mm camera in the Jura, in a wintry, unpopulated landscape. You bring a researcher whom we have seen sitting in the library in Paris before, working through a huge pile of archival papers. We watch him walking and running—away and towards the camera. From a bird’s-eye view we see him looking around in the cave, touching, almost caressing the surface of the sediment. His bodily movements seem cautious and curious, maybe frightened. We watch him looking for history. We hear a whispering voice and the music of Purcell and Monteverdi. There is something slightly obsessive and abundant within these camera movements; a crescendo unfolds, as if there are doubts about whether the methodology will actually work. And once we arrive in the second chapter and know what happens next, it looks almost like an escape—to leave the lonely position of a researcher, to leave the false end of history, to leave deserted France.15 Between the first and the second chapter we fall through the earth, taken away by something blue, traveling underwater travel … and arrive on the other side of the world, in Haiti. And within a second we, the spectators, enter a very different zone. The soundscape has changed completely, with street noise and rap music. The frame is populated with people debating, arguing, laughing. The silence of the library, of books, the lonely reading—all gone. The camera now follows the theater group and it seems that step by step, they are taking over and starting to direct you instead of you directing them.

LH: You are right in identifying a movement from the lonely archive researcher towards something in which I am directed by the situation rather than directing it myself. Indeed, we move from something quite formal, about landscape, text, and archives, towards improvisation, the gradual loss of authorial control, and a focus on people, stories, and play. This is in fact quite a personal movement of mine, towards trying to do things differently while remaining very close to the work of Straub and Huillet. I think this is how I have engaged with the methodologies of Straub and Huillet since I first started making films. Not as a way to identify a problem with their work, but as a way to think critically through it as I try to work with it.

My short film Black Code/Code Noir (2015) opens with a shot that quotes the opening of Trop tôt/Trop tard (1981). Straub and Huillet’s film opens with a camera mounted inside a car circling the roundabout at Place de la Bastille in Paris. In the opening to Black Code/Code Noir, the principal gesture remains the same but I try to create a détournement within Straub and Huillet’s own revolving shot through a series of small changes. Their shot is in the bright daytime, whereas mine is at night (which is also a reference to Les Mains Negatives by Marguerite Duras, a further complication in the reading of this image). In Trop tôt/Trop tard Danièle Huillet reads a letter from Friedrich Engels about the failings of the French Revolution, whereas in Black Code/Code Noir Ana Vaz reads from The Black Jacobins about the beginnings of the Haitian Revolution. In creating a cinematic quotation that détours from the original, I wanted to ally myself with Straub and Huillet’s working methods but create an image that could be the other side of the original, the reverse or underneath, a quotation-image in negative.

With Ouvertures, however, comes a clear shift from one method to another within the film. Rather than a way of making changes to a quotation, this was actually an attempt to speak in a new way, yet the questions—of how to work with actors and language—remain. The formal shift in the film was a way to mark a departure for me into a new kind of cinema informed by experiments with collaboration and improvisation that I had never done before to this extent. Furthermore, Glissant’s play is slowly discarded and forgotten altogether. What constitutes the narrative of the film is a blending-together of scenes written with the Haitian members of the Ensemble and translated into Haitian Creole, and scenes that are entirely improvised—both in terms of what is said and the movements that the scenes create for the camera. In this sense, the mise-en-scène unfolds as the film develops, as the shots roll out into the space of the situation we were filming in. This is why we have many shots of people walking as they talk about their experiences and ideas—the landscape that constitutes the image is determined through the duration of what is being said.

My role in this instance as a filmmaker was one of stepping back from talking about something, and rather listening to what was being spoken of. It is a kind of cinema that follows an ethical principle of images imbued with sound, a cinema that listens to rather than takes from a community. This comes down to a question of knowledge also, and the difference in French between the words entendre and comprendre: the first is a form of understanding that learns through being attentive, the latter through grasping something. Yet the film is of course very much constructed and follows a form of “critical fabulation” in order to tell the stories it needs to tell. But this was done through a long process of learning how to write and speak, both with the camera and the people on screen, as a choral voice, as an ensemble that allows space for a series of different solos or duets within a piece that follows and eventually discards its score.

These conversations began during the preparations for the exhibition “Tell It to the Stones: The Work of Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub,” at the Akademie der Künste, Berlin in 2017. Displayed in two vitrines, Louis Henderson exhibited Overtures: I Build My Language with Rocks (2017, mixed media), assembled as “material for a film on Toussaint Louverture.” This material had been used on a shoot in the Jura Mountains. The footage from the shoot would later became the first part of the film Ouvertures (2020).

Out 1: Noli Me Tangere, directed by Jacques Rivette and Suzanne Schiffman (France: Sunchild Productions, 1971).

Ouvertures, directed by Louis Henderson and Olivier Marboeuf (France-UK-Haiti: Spectre Productions, 2020). The film was developed and written by the artist group the Living and the Dead Ensemble, consisting of: Mackenson Bijou, Rossi Jacques Casimir, Dieuvela Cherestal, James Desiris, Louis Henderson, Léonard Jean Baptiste, Cynthia Maignan, Sophonie Maignan, Olivier Marboeuf, Mimétik Nèg.

Jacques Rivette: Texts and Interviews, ed. Jonathan Rosenbaum (British Film Institute, 1977), 46.

Elke Marhöfer, Jean-Marie Straub, and Mikhail Lylov, “A Thousand Cliffs,” in Point of View – der Standpunkt der Aufnahme: Perspectives of Political Film, ed. Tobias Hering (Archive Books, 2014), 343.

Anna Grimshaw, C. L. R. James: A Revolutionary Vision for the 20th Century (Smyrna Press, 1991), 16.

C. L. R. James, The Black Jacobins: Toussaint Louverture and the San Domingo Revolution (Penguin Books, 2001), xvii.

James, The Black Jacobins, 303–4.

Édouard Glissant, Monsieur Toussaint: version scénique (Gallimard, 1998), 9. “L’ouvrage … il se réfère plutôt à ce que j’appellerai, par paradoxe, une vision prophétique du passé.”

Glissant, Monsieur Toussaint, 12. “J’ai tâché pourtant de résister à un mécanisme simple de ‘créolisation’ dont l’artifice eût été bien évident. La mise en scène de cette histoire peut décider de son environnement linguistique; et la langue créole est suffisamment disponible dans sa non-fixation écrite pour que le metteur en scène et acteurs rejoignent ici et complètent par l’improvisation les intentions de l’auteur.”

Édouard Glissant, Le Discours Antillais (Gallimard, 1981), 267. “On me dit que le roman du Nous est impossible à faire, qu’il y faudra toujours l’incarnation des devenirs particuliers. C’est un beau risque à courir.” (I am told that it is impossible to write the novel of the We, that it will always be necessary to provide the incarnation of particular destinies. This is a beautiful risk to take.)

This process culminated in an exhibition at Olivier Marboeuf’s now closed art center in the suburbs of Paris, Espace Khiasma. The exhibition was called “Kinesis” and it encompassed a program of events, talks, screenings, performances, and workshops, all around the idea of collectively remixing and reediting a film I had made in 2015 called Black Code/Code Noir.

In the essay “Du boucan chez Glissant,” in Sonic Acts: Hereafter, ed. Mirna Belina (Sonic Acts, 2019), Olivier Marboeuf writes of how Monsieur Toussaint describes the process through which Louverture’s dying body (and heroism) decomposes in order to create a fertile ground upon which future collective action can recompose—life, death, and rebirth spiraling together. This is something we tried to translate into the processes of working collectively in Haiti, and is the basis of the work we continue to do.

This approach is not least indebted to cinéma vérité. Rivette describes his own form of cinéma vérité as coming from working with Jean Renoir: “The three weeks I spent with Renoir … made quite an impression on me. After a lie, all of a sudden, here was the truth. After a basically artificial cinema, here was the truth of the cinema. I therefore wanted to make a film, not inspired by Renoir, but trying to conform to the idea of a cinema incarnated by Renoir, a cinema which does not impose anything, where one tries to suggest things, to let them happen, where it is mainly a dialogue at every level, with the actors, with the situation, with the people you meet, where the act of filming is part of the film itself.”

“In June 1980, the Straubs spent two weeks filming in the French countryside. They were seen in places as improbable as Treogan, Mottreff, Marbeuf and Harville. They were seen prowling close to big cities: Lyon, Rennes. Their idea, which presides over the execution of this opus 12 in their oeuvre (already twenty years of filmmaking!) was to film, as they are today, a certain number of places mentioned in a letter sent by Engels to the future renegade Kautsky. In this letter (read off-screen by Danièle Huillet), Engels, bolstered with figures, describes the misery of the countryside on the eve of the French Revolution. One suspects that these places have changed. For one thing, they are deserted. The French countryside, Straub says, has a ‘science fiction, deserted-planet aspect.’ Maybe people live there, but they don’t inhabit the locale. The fields, roadways, fences and rows of trees are traces of human activity, but the actors are birds, a few vehicles, a faint murmur, the wind.” Serge Daney, “Cinemeteorology,” trans. Jonathan Rosenbaum, e-flux Notes, January 17, 2023 →. Originally published in Libération, February 20–21, 1982.