Men dancing tango in a river, Buenos Aires, 1904. Photograph. General Archive of the Argentine Nation.

This essay is part of an e-flux Notes series called “The Contemporary Clinic,” where psychoanalysts from around the world are asked to comment on the kinds of symptoms and therapeutic challenges that present themselves in their practices. What are the pathologies of today’s clinic? How are these intertwined with politics, economy, and culture? And how is psychoanalysis reacting to the new circumstances?

***

In the 1990s, a sociologist friend and I came up with an idea for a self-help book. We imagined that it would become an instant bestseller. Our title was Unleashing the Latin Lover Within: What Tango Can Teach You About Living Well. Two New York book agents were interested. Indeed, the timing seemed perfect: the US was suddenly infatuated with all things Latin—“Latin is hot” was the slogan. Salsa was selling more than ketchup, and a taco-peddling Chihuahua was becoming a national icon. Madonna was playing Evita, enamored with tango, and performing a unique rendition of “Don’t Cry For Me Argentina.”

I closely followed the rising interest in Latin American identity, as I had recently emigrated from South America. I grew up in Buenos Aires, the so-called “world capital of psychoanalysis,” where the name Jacques Lacan is as popular as Maradona or Messi. Though tango is one of the most emblematic symbols of my birth country of Argentina, in my youth, my preferences were instead for reggae, ska, punk, Brazilian music, and American rock and pop. During my student days I studied psychology and worked in journalism, splitting my time between university classes, study groups on Freud and Lacan, and press deadlines for articles.

Now living in the US, I wondered whether my past experience working for several women’s magazines might spur me to write a self-help book. The premise of self-help books is simple: once the solution to a problem has been offered and easily memorized thanks to catchy acronyms, the reader will feel better and improve by identification with a fictional character depicted in the book. Like cookbooks (how often do we actually cook any of the recipes described?), or sex manuals (in which the pleasure is generated by reading the text much more than by any actual realization), the greatest satisfaction is derived not from the following the guidance but from fictional immersion. Self-help books function like literature; that is to say, they grant a cathartic release, leading once in a while to renewal and restoration.

The premise of the book my friend and I were developing was to invite readers to adopt what we coined the “Latin Lover Attitude” (LLA). The LLA would enact a change in disposition, promising more fun and ushering in a freer life spiced up with fire and passion. We argued that contrary to the usual assumption that a Latin lover was a “macho” man, a chauvinistic summation of toxic masculinity, what made the Latin lover irresistible, from Rudolph Valentino to Antonio Banderas, was that these men showed affects traditionally considered feminine. We argued that the virile parade of the Latin lover was a form of feminine masquerade. Alas, our dialectic reversal was deemed to be asking too much of self-help book readers accustomed to clichés and a linear argument. This project, like a timid beginner tango dancer, remains benched for now—but I haven’t fully abandoned my investigation into the link between tango and sexuality.

Indeed, I know quite a number of Lacanian psychoanalysts in Argentina who are devoted tango dancers. They will tell you that tango is about death and sexuality, adding that on the dance floor you find only two types of people: those who are in analysis and those who need analysis. Ask any Argentinean tango dancer about the origins of this rhythmic, glamorous, sensuous dance and they will tell you that tango is not a dance but a feeling, that even before the music was created, tango already existed as the expression of a man and a woman’s mutual need to embrace. Tangueros wax lyrical and believe that tango is not a dance but an emotion. Tango is syncopated love, pure attitude. With the same passion, they deny the hard historical evidence regarding tango’s origins in gender-bending and class-crossing. Tango, born in the late nineteenth century, is the result of a mixture of cultures. It appeared in the cafes, gambling houses, and waiting rooms of brothels in the poorest barrios of Buenos Aires. Most of the time, destitute immigrants and local compadritos would dance with other men. The first women to be included danced tango dressed as men with other women in drag.

As its popularity increased, tango became an international craze and the dance crossed class boundaries—from poor neighborhoods to high-society ballrooms. As it became more acceptable, its queer and working-class origins were erased. Tango lyrics, initially full of sexual references, became restrained. Decent women joined in the dance. Tango, however, remained a predominantly male activity. Groups of men gathered for hours to practice the steps and create new moves, supposedly to improve their dancing and look more attractive to women … and to other men.

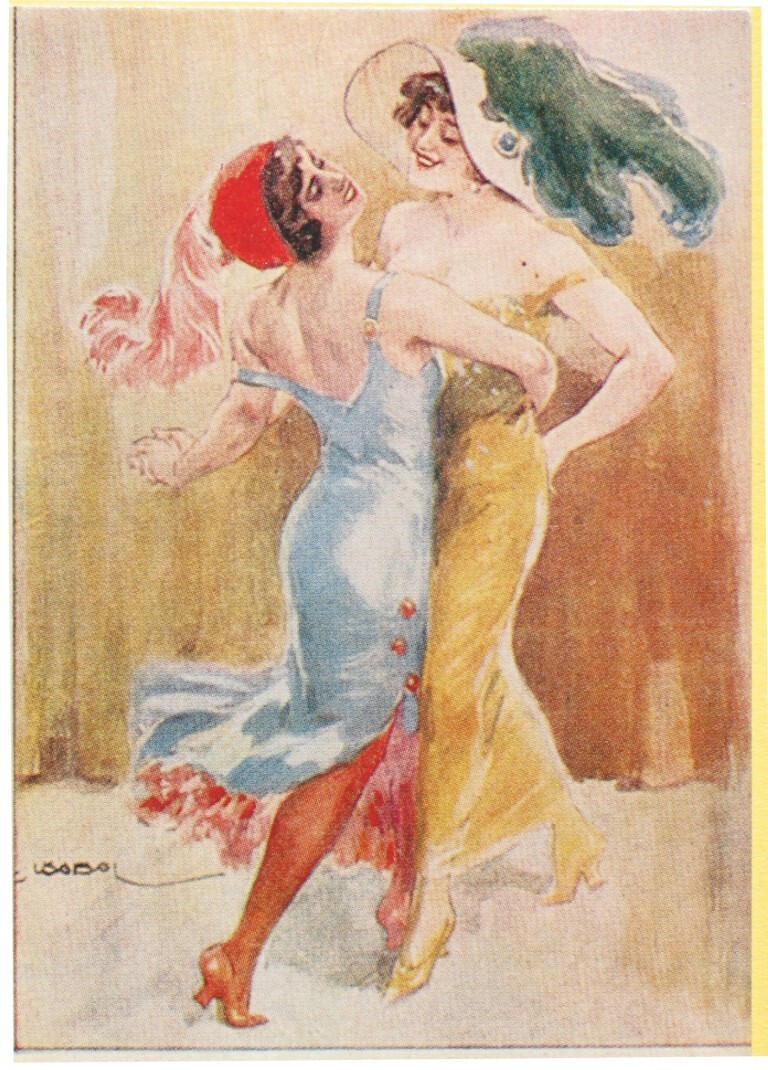

Postcard from the Soviet Union. Private publishing house during the New Economic Policy period, 1920s.

Tango is a melting pot. Jorge Luis Borges described tango’s contradictory origins as a hazy, unreal fiction, for some believe it originates from Argentina, others from Brazil via Uruguay, others from enslaved Africans.1 The tangled myths of tango’s origins persist in the cultural imagination. Rich and poor alike partake, all succumbing to the energy of tango, which manages to combine paradoxical images: a luxurious Parisian ballroom and a poor Buenos Aires port bar; intimate seductions and formal ballroom performances; close physical contact and highly ritualized social interaction; two men dancing a dance of love with earthy qualities, twirling away next to two women in drag, all of them following a two-by-four beat.

Long before the moment of trans visibility made it onto the covers of newspapers and magazines, I started noticing something unusual in the complaints of my psychoanalytic patients. I heard from my cis, female-identified, hysteric patients the question: “Am I straight, or am I bisexual?” They also asked more and more questions like: “Am I a man or a woman?” I linked their uncertainty about their gender with my trans-identified analysands; for them, suffering was caused not by the question but by the answer, like when someone says, “I was assigned female at birth but always felt I was a boy.” The very possibility of embodying a different gender from the one assigned at birth reveals that the materiality of the body is not a given. Furthermore, it shows that body and gender consistency is a fiction that is assumed through identification. Borges writes that many early tangos evoke a duel to the death—two compadritos defending their honor by fighting for the same promiscuous woman, exchanging knife thrusts outside the dance hall. Tango, insists Borges, is a matter of life and death. In the same way, I became more aware of how much the issue of mere survival has indelibly marked the trans experience.

Around this time, I was hesitating to write another book, this one about Lacan and tango. A little anecdote will contextualize my hesitation. Roy and Silo were two male penguins living in New York’s Central Park Zoo. A zookeeper noticed them taking turns trying to hatch a rock that looked like an egg. Seeing this, the keepers gave them the second fertilized egg of a male-female penguin couple that had been unable to hatch two eggs at once. Roy and Silo successfully hatched the egg and raised the healthy young chick, a female penguin named Tango. The story was the basis for a delightful children’s book, And Tango Makes Three. The penguins being quite explicitly a same-sex couple, many American parents objected to the book. Parents of students at a school in Illinois requested that the book be placed in a section of the library with restricted access. In a Missouri school library, after many parents objected, the book was relocated to the nonfiction section. The American Library Association reported that And Tango Makes Three became one the most protested books between 2006 and 2010. One parent from Maryland, arguing that the book presented issues of sexuality in terms unsuitable for young children, requested that the book be removed from the children’s library section and shelved with adult books on sexuality. The fact that the penguins “slept together” was claimed to be an obvious reference to sexual behavior. Meanwhile, in Chico, California, parents, teachers, librarians, and school administrators formed a committee and voted to retain the book in the library. Invoking the First Amendment, public libraries established that such censorship was unconstitutional. And Tango Makes Three has won numerous literary awards but continues to be at the top of the most-banned-books list. Most recently, in February 2023 it was banned in elementary students in Florida for what the school board deemed “sexual innuendo.”

This provides a good example of what Lacan called the signifier. Its randomness (the fact that tango is both the name of a dance and the name of a penguin) is transformed into an allegory by the social context. In this allegory, I find the model for my own quandaries and those of my analysands. How can we learn from these curious equivocations? Is there a logic of gender and sexuality that can teach us to make sense of trans issues as the next civil rights frontier? Are we changing the way we talk about sex and gender?

My tanguero friends and even my dear cousin, a highly regarded tango instructor when she lived in Buenos Aires, still swear that tango’s origins are heterosexual. They argue that the electrifying, sensuous, amorous embrace practiced among men or women in drag simply served as a rehearsal of a male-female activity in which men led and women followed. This wrong assumption may have cost the job of Valerie Plazenet, a ballroom dance instructor at France’s elite university Sciences Po in Paris. After several students complained about her refusal to use gender-neutral language such as “leader” and “follower” instead of “man” and “woman,” Plazenet was forced to resign in December 2022 after a public controversy. Some felt offended by her sexism and unwillingness to use more inclusive language; others defended her as being pursued by excessive “wokism.” In her declarations, she asserted that she was proud of being a woman and that “woke theories wipe out the term ‘woman’ in spite of the fact that a woman’s body is greatly different from a man’s.”2 In saying this, she harkened back to old biological essentialisms, reproducing the binarism most of us thought we had overcome and that even tango lyrics expose as preposterous in its absolutism. Here is one example out of many, from a 1922 song called “Patotero Sentimental” (Sentimental Gangster): “Ya los años se van pasando / y en mi pecho no entra un querer / en mi vida tuve muchas, muchas minas / pero nunca una mujer” (Years pass by / and in my chest no love enters / in my life I had many, many strumpets / but never a woman).

The recent Sciences Po controversy about holding onto the man-woman binary recalls a fictional scenario from Lacan illustrating how language sets up sexual difference as an impasse. A brother and sister take a train journey, sitting across from each other in the compartment. As the train pulls into a station they look out at the platform from the window and the boy exclaims, “We have arrived at Ladies.” The girl states, “You idiot! Can’t you see we are at Gentlemen?” Lacan says that they will never reach an agreement, Ladies and Gentlemen being in fact the same homeland. Neither will give any ground, as if one’s success depends on the other’s losing. The irony is that both public restroom doors are identical and only the signs make them appear different. Neither child has arrived at Ladies or Gentlemen, as they believe according to their subjective, skewed perspectives; they are both wrong. This shows that the gender dynamics of tango remain problematic today. Many types of contradictory and equally persuasive conclusions can be drawn about tango’s genealogy. Instead of writing a book on tango and gender according to Lacan, I prefer to keep tango’s mystery veiled while I tango in Buenos Aires’s villa Freud.

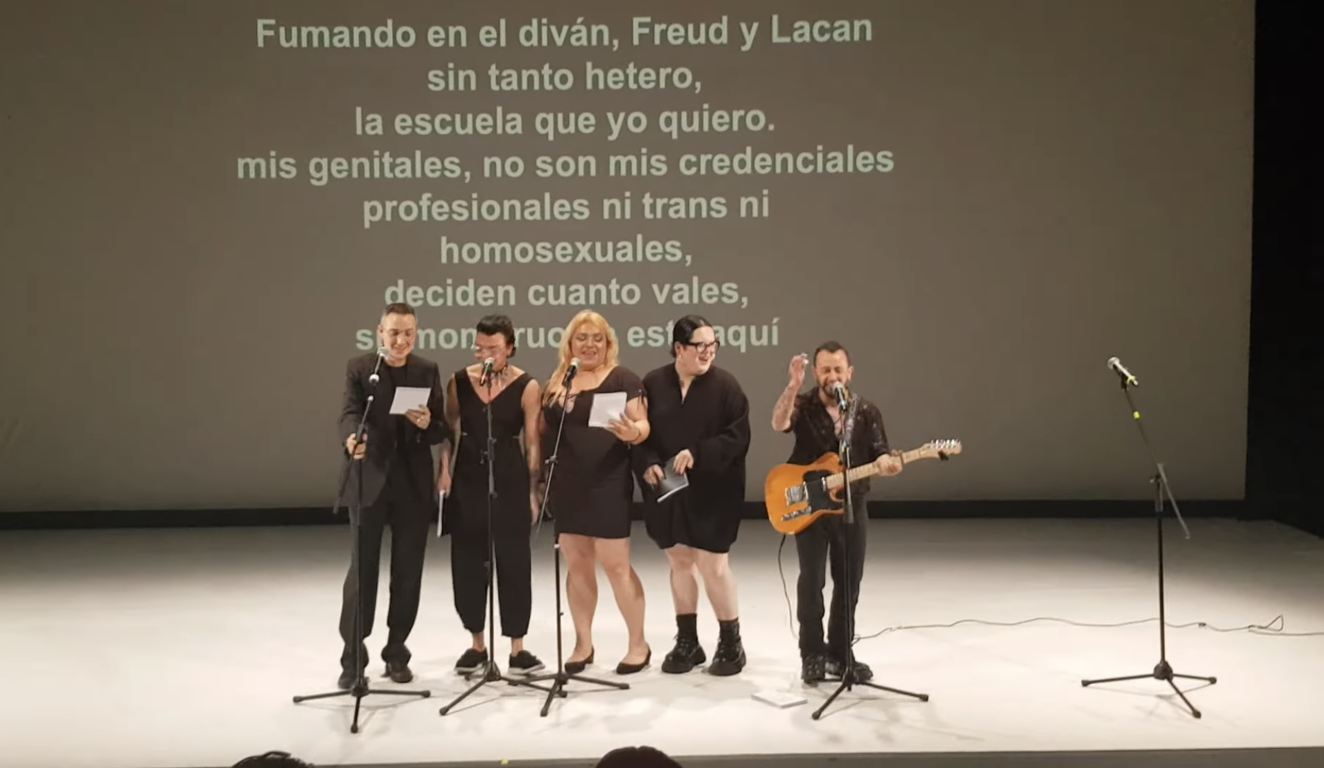

Paul B. Preciado, Bambi, Víctor Viruta, Andy Díaz, and Fabiana Hernández, “The Tango of Freud and Lacan,” Centro Cultural Conde Duque, Madrid, 2023.

As I was writing this text, Paul B. Preciado presented a play-reading of his recent book Can the Monster Speak? Report to an Academy of Psychoanalysts at Centro Cultural Conde Duque in Madrid. This controversial lecture had first been given at the École de la Cause Freudienne annual conference in Paris. In one of the last in-person meetings before the Covid pandemic, Preciado spoke to an international audience of 3,500 Lacanians who were convened in a meeting around the issue of “Women in Psychoanalysis.” The conference took its inspiration from the observation: “In psychoanalysis, there are women!” Preciado, a well-known male transgender figure, was the keynote speaker. Preciado’s speech created what was described by those in attendance as “an earthquake.”3 Controversy was triggered by the opening words: “Ladies and gentlemen … and those who are neither ladies nor gentlemen.”4 Preciado pointedly asked if there was at least one psychoanalyst in the huge auditorium who was openly queer, trans, or nonbinary. The response was a glacial silence interrupted by nervous giggles. He continued by asking whether any of the psychoanalytic institutions present at the meeting assumed responsibility for the current changes in what he called the “regime of sex, gender and sexual difference”—that is, the way we think, talk, and theorize about gender and sexuality.5

The audience was divided between those who cheered enthusiastically and those who booed, including a few who demanded that Preciado immediately leave the premises. One woman expressed her anger so loudly that she was heard by Preciado from the stage: “We should not allow him to speak, he is Hitler!” she shouted.6 While this horrible comparison recognizes Preciado’s position as an important political leader, it paints him as authoritarian and dictatorial. The speech was interrupted by the organizers, who told Preciado that his time had run out after he had only read one quarter of his lecture.7 Preciados’s presentation was captured on mobile phones and the video went viral like a leaked sex tape, sending shockwaves across the psychoanalytic world.

Preciado wittily alluded to Kafka’s 1917 short story “Report to an Academy.” In the story an ape named Red Peter, who has learned to behave like a human, presents a report to an academy of experts. The report is the story of how he achieved his transformation into an acceptable educated European. However, he is still ready to pull his pants down whenever he needs to show a bullet wound commemorating his capture on the African Gold Coast. Similarly, Preciado exhibited himself as a transsexual specimen like Kafka’s ape, who ironically claimed that he was as “human” as anyone in the audience, the product of a deliberate transformation. Remaining with Kafka, I will invoke his “Metamorphosis” and argue that psychoanalysis is already undergoing a mutation, whose first step could well be a sex change.

The sold-out March 2023 reading in Madrid included a group performance of “The Tango of Freud and Lacan.” In a two-by-four rhythm, Preciado, Bambi, Víctor Viruta, Andy Díaz, and Fabiana Hernández sang a tune that joyously celebrated trans life. It began: “Fumando en el divan / Freud and Lacan / la escuela que yo quiero / Mis genitales no son mis credenciales / profesionales ni trans / ni homosexuales / deciden lo que vales” (Smoking on the couch / Freud and Lacan / the school I want / my genitals are not my credentials / professional or trans / or homosexual / they do not decide what you are worth.” The song ended with: “Viviendo sin temor / mi identidad, mi amor / mi cuerpo y su sabor / y darle a todo su sabor” (Living without fear / my identity, my love / my body and its flavor / and giving everything its flavor). I leave you with Preciado’s tango, and in its wake with a psychoanalysis moving beyond fishnet stockings and fedoras, stepping out from the Freud waltz to a Lacan tango and beyond.

Jorge Luis Borges, “Historia del Tango,” in Borges Cuenta Buenos Aires (Editorial Emecé, 2016).

See →.

Paul B. Preciado, Can the Monster Speak? Report to an Academy of Psychoanalysts (Semiotext(e), 2020), 11.

Preciado, Can the Monster Speak?, 17.

Preciado, Can the Monster Speak?, 17.

Preciado, Can the Monster Speak?, 11.

Preciado, Can the Monster Speak?, 11.