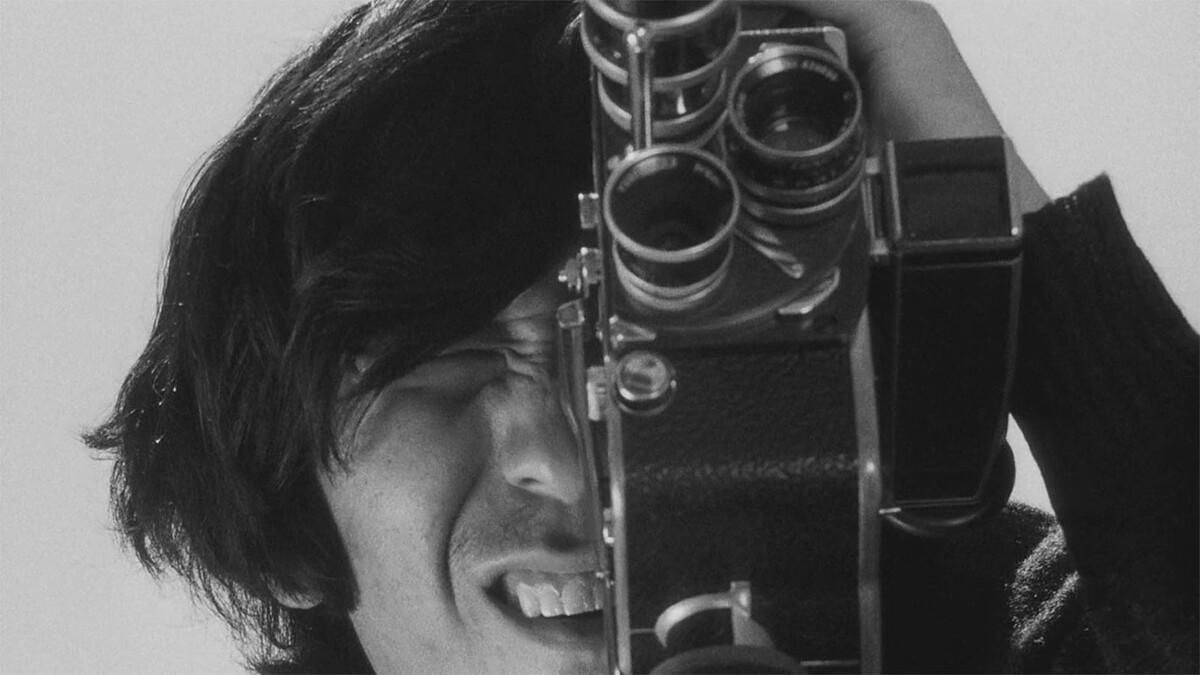

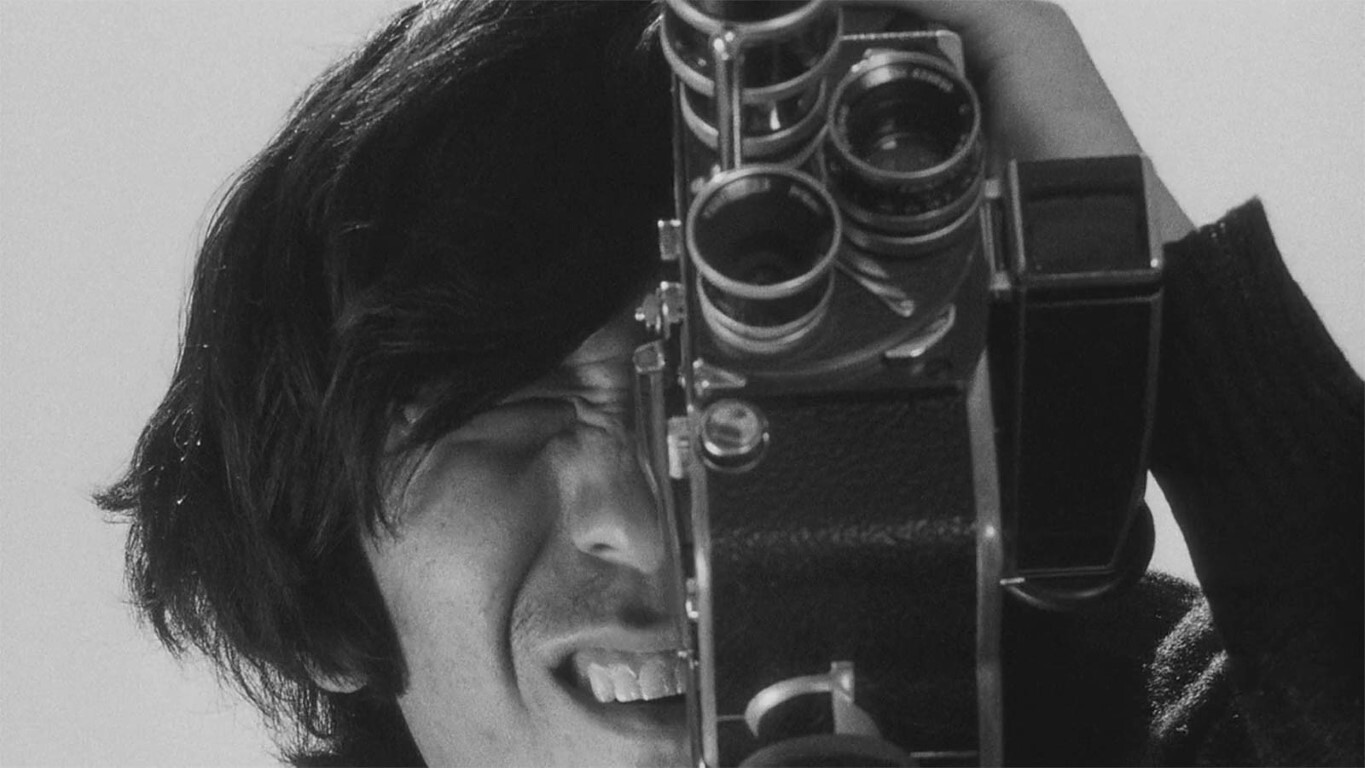

Still from Nagisa Oshima, Tōkyō Sensō Sengo Hiwa (The Man Who Left His Will on Film), 1970

This essay, originally published in 1971, appears here in conjunction with the screening program Landscape Theory: Post-1968 Radical Cinema in Japan, curated by Ethan Spigland and Go Hirasawa, taking place at e-flux Screening Room and the Pratt Institute on March 24, 25, and 27. The program is focused on “landscape theory,” a theory of politics and revolution proposed by film critic and anarchist Masao Matsuda in 1969. The program showcases films by Masao Adachi, Koji Wakamatsu, and Nagisa Oshima, among others, and aims to situate landscape theory in its Japanese historical context while assessing its relevance today.

***

In Nagisa Oshima’s work from 1970, Tokyo Senso Sengo Hiwa (He Died After the Tokyo War, in the overseas edition), the term “war” does not refer to the Second World War. Certainly, war on the scale of world war disappeared from the earth when Imperial Japan surrendered to the Allies in 1945. However, have wars really been wiped out completely in the twenty-six years since? The answer is no. To prove this it is enough to recall the Korean and Vietnam Wars, not to mention countless civil wars—including the civil war in China that ended in the victory of the Communist Party. The people of Vietnam have indeed continued fighting twenty-six years in the “postwar” period. In his famous message (“Create Two, Three … Many Vietnams, That Is the Watchword,” published on April 16, 1967), Che Guevara characterized the postwar era as “this peace that we are willing to fight for.” There was no such thing as “postwar” for the people of Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

There was, however, one fortunate nation-state that could enjoy “this peace.” It was Japan. Under the new postwar constitution, Japan proclaimed its abandonment of all belligerent rights—while appearing “as a merchant of death” in the Korean and Vietnam Wars—and developed and strengthened capitalism as its system of control. Japan’s rulers built an unofficial army that in fact violates the county’s own constitution, and now with enormous economic and military power they are in the process of strengthening their direct expropriation of the people of Asia. Nevertheless, Japan enjoys “peace” without having a direct connection to the “wars” taking place after World War II.

Students—not college students but high school students—who are characters in Oshima’s new film inevitably aggressively oppose this false system of control in Japan. At the end of the sixties they launched rudimentary armed struggles in major cities such as Tokyo and Osaka, playing a part in worldwide student power. The radical factions among students at that time named their struggles the “Tokyo War” and the “Osaka War.” Why did the Japanese students name as “wars” what students in France would certainly have called examples of “May Events”? We can find the answer in the lack of a “revolutionary” tradition among the Japanese people, as well as in the fact that Japanese students are pursuing a particular policy in an attempt to expand domestic “wars” (civil wars) abroad, and to develop them into world revolutionary wars, which can then be united with international liberation struggles.

The characters in Nagisa Oshima’s new film are a group of students who experienced wars in terms of what was mentioned earlier and are now living in the midst of a postwar period. After fighting continuously for three years in the wake of fall 1967, they were completely defeated by the police force, a strong vanguard for the rulers of Japan. Thirty thousand people were arrested, ten thousand people were prosecuted, and now as of spring 1971 about one thousand people are still in jail. The system’s wall was so thick that the students’ attempt during the Tokyo War was not successful enough to break through it. Of course they could not help but change tactics from the previous popular street struggle—which furthermore could be called a protest at the convenience of the rulers’ schedule. Urban guerrilla tactics, including the use of an elite minority, were used, and so-called hit-and-run tactics were emphasized. The hijacking to North Korea that surprised the whole world was one of the successful examples.

But for them, the restrained urban guerrilla struggle means days of ordeals even harsher than the flashy popular street struggles, because, as the Chinese saying goes, as a fish in the water, guerrillas have to operate in the people’s ocean. In other words, unless they can hide themselves amongst the masses, who live as calmly as water, tirelessly year in and year out, rather than in the crowds on the streets, who are excited like boiling water, they will be hunted down by the security police with noses as keen as dogs. Thus in the postwar period, which continued up to the time of that frenzied war, militant students were forced to immerse themselves in clear, colorless water. The living space of the popular masses, as chilled water, while having infinite kindness, rejects with infinite severity those who cannot fit into it. The students are again in the midst of a difficult battle.

I believe that the above explanation can help to understand the reason why landscapes are frequently shown in Tokyo Senso Sengo Hiwa as a will that is introduced through a “play within a play” technique. To put it metaphorically, landscape, like water in the ocean, is something that becomes visible as a mundane place anywhere the popular masses live. It is a severe space that gently embraces the characters on one occasion, and on another occasion holds one of them tight in its deathly jaws. However, students in Japan reached an extreme where, unless they first discovered themselves capable of surviving in this landscape, they could not see through the enormous controlling power beyond the landscape. Their difficulties here can be called the “Tokyo landscape war” in Oshima’s new film. It is no accident that the place where the protagonist kills himself (in both illusion and reality) is an important site in the Japanese capital, overlooking the Diet Building. He is in the tragic position of having no choice but to throw himself into the landscape that is spreading over it like a veil.

In this sense it can be said that progressive young students in Japan are shifting from the situation of an extraordinary battle that was oriented towards a utopia that doesn’t exist anywhere, to that of the everyday battle for how they can resist landscape as a place that exists everywhere, and how they can overcome it. (Landscape theory is a major theme in the militant intellectual public sphere in Japan.) Because the process of this transition is appropriately conceived as “film as a will” in Oshima’s new film, it can be asserted that this work, like Oshima’s films up until now, is a film of premonition that anticipates what will come in the future. This achievement is owed to Masataka Hara, the young Japanese writer (nineteen years old at the time) who cowrote the screenplay, and to Oshima’s group that decided to use him. Those who see the student group that appears here as a mere film production collective must be really hopeless onlookers, I believe.

“Why landscape war?”(Naze fukei senso ka?) first appeared in Masao Matsuda, Fukei no Shimetsu (The extinction of landscape), 1971.