The Yuyachkani group demonstrating in Plaza Túpac Amaru in Lima, January 13, 2022, in solidarity with the victims of massacres.

A tank destroying Entrance Gate 3 of San Marcos University (Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos) on January 21 has become a powerful image of the recent outbreak of violence in Peru. A contingent of police officers entered the university, which is the oldest university in the Americas, throwing tear gas bombs and arresting students and regional delegations that were staying peacefully in the university’s housing.1 The detainees—which included pregnant women and elderly people—travelled to Lima from other regions of Peru to exercise their right to protest. They did so despite acts of violent repression by the police in their home cities that have so far resulted in nearly sixty deaths and more than 1600 injured civilians.

Disempowerment has prompted people from all regions of Peru to travel to Lima. This influx is due to the limited influence of regional actors in the larger political arena, not only because of the centralized government and parliament system, but also the lack of national political parties with subnational competences, and the centralism of the media and academia. When police entered San Marcos University, nearly two hundred regional delegates and students were forced to the ground, intimidated, stripped of their belongings and documents, and abused with racist insults, enduring what Amnesty International and other human rights organizations have characterized as a “disproportionate use of force.”2 They were then detained for two days on trumped-up charges for “usurpation,” aggravated robbery, and property crime. Many of the detainees spoke Quechua as their mother tongue and were not offered translators to aid in their defense. They were also very distrustful of any legal support offered to them, which is evidence of their lack of trust in anything whatsoever coming from the city of Lima. This is based on a prevalent racialized vision of society, in which rural and Indigenous populations are still treated as inferior in contrast to those residing in the capital and on coast of Peru.

Peru’s current government is often described as a “civic-military authoritarian regime,” with practices reminiscent of those used during the dictatorship of Alberto Fujimori (1990–2020). The repression of the police as they entered San Marcos University is laden with a strong historical symbolism, since Fujimori’s government used the police to suppress “subversive” elements and infiltrate “terrorist” groups.

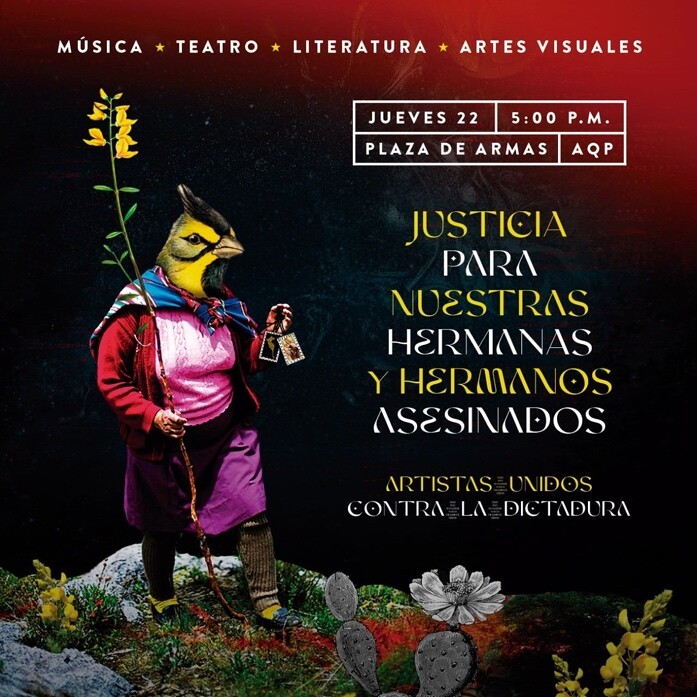

Poster by the Red Nacional de Trabajadores de las Artes y las Culturas, calling for peaceful demonstrations nationwide.

San Marcos University represents the distortion and disfiguration of Peruvian society. By inviting the regional delegations to stay at the university, the students were not only providing them with a safe place but also helping to create an outlet for the outer regions’ deep contempt and lack of confidence in the centralist powers in Lima. The dramatic entrance of the police was welcomed by the university’s rector, Jerí Ramón, who, for several months, along with other unscrupulous authorities and the support of Congress, have been trying to delegitimize the National Superintendency of Higher Education—the body created to oversee the quality of university education in Peru. During the Fujimori regime, the liberalization of higher education resulted in a group of private universities of dubious quality, which became facades and sources of financing for political parties, whose founders and their families are in practice the “owners” of the party, influencing parliament and local governments in order to maintain their poor-quality education. Even though some regions earn significant revenue from extractive industries such as mining, corruption and mismanagement have prevented these benefits from reaching the local population. This politics led to a dispersion of citizens’ votes, resulting in a multitude of parties with little parliamentary representation. Worst of all, it dismembered the development and involvement of grassroots organizations in political life, which is one of the causes of the current social tensions in the country.

Stemming from the demands of the regional delegations, representatives of the population have called for immediate general elections, the resignation of Dina Boluarte’s brutal and repressive government, the closing of Parliament, and a new Constituent Assembly. Although the regions still lack leadership and representation, it is important that regional demonstrations build a platform for political change, something that has not happened before.

Steven Levitsky, a professor of Latin American studies at Harvard University, laments that “there really are no political parties in Peru; they are all personal vehicles.”3 As a result, there is no one who can represent popular discontent and support the development of a platform for political change. This failure of representation translates into a lack of direction and dialogue. The savage response from the government has fueled the population’s anger, thus leading to outbreaks of violence. Many of these acts are not new, as the history of Peru is full of social uprisings, but now they face immediate attempts to discredit them from both the extreme right and the mainstream media. Their message is that every mobilization is a premeditated act coordinated by either Pedro Castillo from prison, terrorist networks, or external agitators such as Evo Morales, thus invalidating the anger and indignation displayed by the people of Peru. The mainstream media has not been open enough to report on the magnitude of the conflict, a bias that obscures the visibility of regional actors in favor of a single point of view, that of Lima.

PERU ROTO by Carlos Sanchez. Public intervention and photographic record in Arequipa.

Today there are two important elements that have noticeably changed. First, the groups in revolt are not only comprised of poor peasants but also merchants who have learned from capitalism and are therefore much more informed and autonomous in terms of organization and economy. Particularly in the south of Peru, there is a strong Andean community structure and a very widespread form of collective organization and decision making. These are no longer the humble peasants from rural areas who were once abused and killed by the forces of law and order. The second element is that Peru is not an isolated country but globally connected, and pictures and videos of what is happening in the country circulate around the world, picked up by global media, as well as independent local media outlets in Peru. Meanwhile the mainstream national media and newspapers work to distort and manipulate reality.

In this context, what is the response of the art and culture sector? During the years of the Fujimori dictatorship, art and culture workers took to the streets to mobilize and organize acts that the writer and social scientist Victor Vich described at the time as “symbolic disobedience.”4 These acts redefined the meaning of the political and the communal, to envisage new relationships between civil society and the state. In Lima, initiatives such as La Resistencia and the Colectivo Sociedad Civil articulated powerful symbolic performances and actions aimed at criticizing the official imaginary of the regime using public space. But these groups did not manage to sustain a long-lasting movement. Such is the distortion of our times that La Resistencia is currently the name of an ultraright shock movement that organizes fascist demonstrations, destroys shops, and breaks into public buildings. Today, in order to organize powerful symbolic actions to criticize the current regime, it is necessary that these voices do not come from all-powerful Lima.

In December 2022, when the wave of violence and social mobilizations began, a group of artists from different regions began to promote the Red Nacional de Trabajadores de las Artes y las Culturas (National Network of Art and Culture Workers).5 The Red’s proposal—which is still in the making—is a response to centralized government and isolated initiatives: they want artists and cultural workers to speak out jointly and peacefully, and to question the relevance of their practice in Peruvian society. The Red also seeks to defend and promote the rights of art and culture workers, with advocacy at regional and national levels. A national coordination was thus formed to work in a decentralized manner on initiatives that promote spaces and platforms for artistic and cultural exchange. Lima was deemed to be “just another region” so as not to fall into the usual privilege accorded to the capital. This is significant because the outer regions are where nearly all the deaths and most of the abuses have been perpetrated by the government. But it is also in the regions where conditions for artists are much more challenging and precarious and where minority groups are deeply marginalized. With few cultural institutions in regional and local governments, and in many cases a traditionalist and patrimonialist view of culture, or the instrumentalization of culture as a means of propaganda and individual interests, the Red aims at building awareness of the importance of art as a social practice.

The Red coordinates and disseminates nationwide artistic actions in public spaces, creating a contemporary message that promotes diversity and fights against polarized debates, valuing and respecting the complexity of the other. Their aim is to turn public spaces into places of intergenerational and intercultural discussion, integrating civil society in the dialogue and emphasizing the right to life when it is most at risk. Today’s violence and deaths are reminiscent of past years of violence, when armed conflict mainly affected the most vulnerable and isolated populations, and the life of an Andean peasant was worth very little.

Public intervention at the gates of the City Cathedral in Huánuco, Peru.

The Red also seeks to build awareness through media and social networks by spreading the hashtag #ArtistasUnidosContraLaDictadura to announce and call for different activities taking place nationwide. These types of initiatives could be seen as a sort of decentralized autonomous organization controlled by the artists rather than directed by a particular central body. We have been witnessing the emergence of social movements that work from “collective” action to “connective” action for quite some time,6 which means that in addition to the use of hashtags and social networks, they also add a new symbolic power where the flow of information spreads to different networks at a national level, displacing traditional media outlets that do not share this type of content. This symbolic action also naturally creates an archive of information that is a basis for collective memory.

The Red uses as its main symbol an anthropomorphic representation of a woman of the Andes with a bird’s face carrying a broom flower in her hands. This alludes to the traditional Ayacucho huayno, a genre of popular Andean music and dance, which is also associated with the police repression that left more than twenty dead—many of them schoolchildren—during protests against the government of General Juan Velasco Alvarado in Huanta, Ayacucho, in 1969. The Yuyachkani group, a well-known theater collective, also used this same figure, with actors generating a relational and communitarian experience during recent protests.

The Red encourages symbolic actions that have taken place in one city to be reinterpreted elsewhere. Such is the case with PERU ROTO, an intervention and photographic record in Arequipa where, using stencils in the shape of Peru, an artist spray-paints this shape over cracks in the pavement. The resulting Peru-shaped red stains on the streets symbolize Peru’s social fragmentation. These are photographed and video-recorded to be shared on social media. This type of distributed media allows the members of the group to achieve their aims more effectively.

San Marcos University not only represents the clash between the regions and the capital, but also symbolizes how education threatens the neoliberal system by creating a social understanding of reality and the construction of citizenship. The outbreak of social unrest in Peru might not be solved with artistic demonstrations. But what the Red and other social groups and university students are demonstrating is that a new type of representation can emerge when citizens organize themselves in decentralized movements that understand each other and are systemically part of the social tissue of a nation. Together, they fight for the rights of those who are unheard, humiliated, marginalized, and mistreated. These platforms can go beyond channeling protests to become citizenship movements, both national and decentralized. As long as grassroots organizations do not participate actively and critically in the national decision-making process, Peru will never be able to respond to the real needs of the population.

The author wishes to thank the members of the Red Nacional de Trabajadores de las Artes y las Culturas.

Dan Collyns, “Police Violently Raid Lima University and Shut Machu Picchu Amid Peru Unrest,” The Guardian, January 22, 2023 →.

“Peru: Authorities Must Immediately Cease Excessive Use of Force Against Civilians and Prevent Further Deaths,” amnesty.org, January 10, 2023 →.

Quoted in Adriana León, Tracy Wilkinson, Patrick J. McDonnell, “In Peru, President’s Ouster Just Latest Manifestation of Extreme Political Turmoil,” Los Angeles Times, December 11, 2022 →.

“Desobediencia simbólica: Performance, participación y política al final de la dictadura fujimorista,” in La cultura en las crisis latinoamericanas, ed. A. Grimson (Buenos Aires: CLACSO, 2004).

W. Lance Bennett and Alexandra Segerberg, “The Logic of Connective Action,” Information, Communication & Society 15, no. 5 (2012).