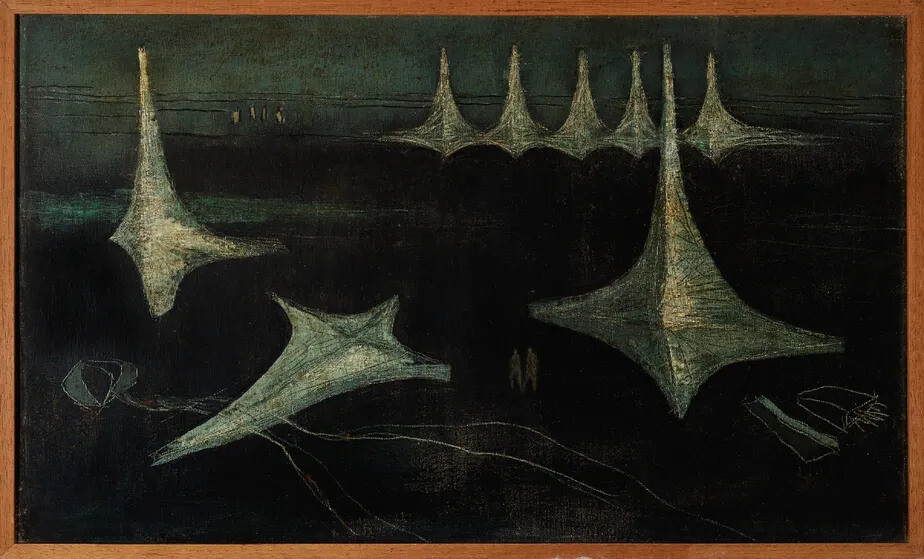

Oscar Niemeyer, Ruins of Brasília, 1964.

See! No one attended the formidable

Burial of your last chimera.

Only ingratitude—this panther—

Was your inseparable companion!—Augusto dos Anjos, “Intimate Verses”

Round 1: Cinderella’s Dreams

Brasília is sleepless. It has been for over a week now. The insomnia may last one more hour, three more days; it may last its lifetime, as the doctors, jurists, and astrologers of the South say this sleeplessness has no end date or deadline. It is out of time. Brasília, in her fine lines, in her atemporal buildings that glance at themselves through now desolated, shattered windows, that breath the now uncleanable smell of excrement left last week in the vast rooms of the Senate—Brasília is the sleepless night. A night not of mourning, history, or stars but merely endless in its prolonged absence, as it looks for the solitude of its pillow. Brasília is sleepless, sing her a lullaby. Hold the city in your arms like a stillborn baby that has lost the capacity to close its eyes. Carefully whisper the well-known Brazilian lullaby: “Sleep baby / Or Cuca will come and take you / Dad is in the fields / Mom went to work.” But this lullaby will not work because this is an impossible sleeplessness. It has nothing to do with the Cuca, the monster of Brazilian folklore; it is better grasped in terms of a somnambulist who has awakened in a stupor but prefers to keep walking, pretending that it is crawling like a child into mother’s lap. Brazil pretends it is still a child because it has never lost its fear of the dark. But the lights have all gone out, extinguished by one of the many men in green and yellow.

In a 1970 chronicle, Clarice Lispector writes that Brasília, the then ten-year-old capital of the country born out of Niemeyer’s drawing compasses, is the “image of her insomnia.” This insomnia, she writes, is “neither beautiful nor ugly, it is me, it is my astonishment.” One could say that the city slept in the astonishing solitude of not having a past, not having a history, or as Lispector puts it: “Brasilia has a splendid past that no longer exists.” And she goes further into the wild heart of the city, inventing this splendid past to say finally in the chronicle that the city’s beauty comes from its “invisible statues.”1 These invisible statues are now out on the grass of Brasília’s main square, mumbling incomprehensibly among themselves about how the slumber of their modernist fortress could have been penetrated. They will solemnly agree to having heard some incomprehensible noises in the past, but nothing like this punch, nothing like this jab to the heart of their invisible marble bones, which has woken them from their indifference to the sight and sound of the world.

Where did this punch come from? More dramatically, who punched the capital of Brazil? Was it solely Bolsonaro’s mob, entering history through the shattering of glass and transparency? I write here to track punches; I write here amid punches and on the cusp of a knockout. I suspect that the first punch came from a loud sound system at Disney’s Magic Kingdom amusement park in Florida, letting ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls from around the planet know that the park was about to close, as Cinderella’s leitmotif sounded.

I like to imagine Mr. Bolsonaro at Magic Kingdom on January 8. It matters little if he was actually there or at a nearby KFC, which he is a fan of, enjoying his vacation in Orlando after losing Brazil’s presidential election. No matter where he was that day, while his gang, escorted by policemen and soldiers, took over the buildings of Brazil’s capital, he undoubtedly heard Cinderella’s theme in his mind. After all, entering the magic kingdom thanks to a perfectly fitting shoe is a much easier path than the Golgotha of history. But between Christ on the holy cross and Cinderella’s election by the shoe, the same principle is transposed: one is saved and released of all unrighteous mortal suffering by the conformity of body to object in the instant of kairos. Bolsonaro must have thought that Brasília’s fall was his magical shoe in which he could step away from blood and martyrdom, away from becoming the lamb of history, and directly into the magic kingdom of his envisioned barbaric world. He dreamt there, in Orlando, with Cinderella, not with his supporters back home, who had crafted a messianic role for him that he did not actually want. These supporters had been constantly claiming, since Bolsonaro’s election loss, that it would take a mere seventy-two hours of unrest, three days between death and resurrection, to clear a path for the ex-president’s return. When they failed to bring him the shoe in their chaos, he condemned them on Twitter and went back to Disney’s Magic Kingdom, afraid of jail. Meanwhile, his arrested criminal supporters still dream of seventy-two hours of redemption, deliverance, and the second coming.

In Paul’s famous second epistle regarding the imminence of Christ’s return, he addresses the euphoric Thessalonians, who live as if the parousia, the second coming, is seventy-two hours away. In this text, Christianity first sees the emergence of the katechon: “And you know what is now restraining him, so that he may be revealed when his time comes. For the mystery of lawlessness is already at work, but only until the one who now restrains it is removed.”2 The katechon is consecrated as that which simultaneously restrains the forces of evil, the chaos of the Antichrist, and, in this restraining, delays the second coming of Christ, who can only fulfill the eschatology in the darkest of nights. The katechon does not allow one to live in the imminence of the second coming.

Carl Schmitt, the famously unapologetic jurist of the Third Reich, asserted that for Christianity there was no other vision of history besides that of the katechon. This is the case because

the vivid expectation of an imminent end seems to take away the meaning from all of history, and it causes an eschatological paralysis for which there are many historical examples. And yet there is the possibility of a bridge … The bridge consists in the conception of a force, which defers the end and suppresses the evil one. This is the Katechon.3

If history after Hegel was understood as the process of the world becoming conscious of itself— the realization of Geist in history as brutality and violence, up to the final comprehension of humans as pure negation—in the restraining figure of the katechon the historical process acquires the image of its end. Self-consciousness prevents the forces of evil insofar as it preserves the lesson of the historical process and its martyrdom of negation and annihilation; it restrains one from going back to history and its chaos.

On January 8, Bolsonaro supporters believed that they were rupturing the katechon from the inside. And although many of them knew that this would bring the darkest night for themselves in the form of institutional repression, they didn’t care; they were confident in their engendered parousia—or did they acknowledge that they were searching for the Antichrist? No matter the answer, no matter the confusion of tropical Christian eschatology, this reading misses a crucial detail of the invasion of Brasília, one that even the armed invaders may have missed. What these people running around Brasília’s invincible solitude, destroying its architecture that forbids ruins, were searching for was a profanation of a dead body, a buried body that nonetheless keeps fertilizing Brasília’s impossibility of ruins. One can find this blasphemy, this curse, in a stabbed painting in one of the halls of the Presidential Palace: the painting As Mulatas by one of the founding fathers of Brazilian modernism, Di Cavalcanti.

“Mulata” is one of the most untranslatable words in Brazilian Portuguese, but it is best defined as a woman of mixed race. Cavalcanti painted several of them, always with a melancholic gaze towards an invisible past; they are immersed in his out-of-time landscapes that, no matter if they are filled with trees or fragile incipient buildings, seem beyond change. The mulata, in this context, is more than a celebration of Brazil’s miscegenation or its supposedly multiracial democracy; it is a monument to immobile synthesis.

Brazilian modernism was defined by its notion of anthropophagy. Its maxim was that it was possible to devour otherness, ingest any antithesis, and produce a sensuous tropical dialectic without strife between the inner splitness of the national and the foreigner, high and low, Brazil and world. To modernists, Brazil was defined by its capacity to appropriate and make the world its own. What anthropophagy hides is what Oswald de Andrade, its most rigorous exponent, identifies in his “Cannibalist Manifesto”: “Down with the histories of Man that begin at Cape Finisterre. The undated world. Unrubrified. Without Napoleon. Without Caesar.” More than a rant against European and Iberian domination over the imaginary of Brazil, Andrade’s manifesto conjures a dream of never becoming historical, an after-history, an end of history even before its beginning. This dream is fueled by the katechon force springing from the mulata’s sad glance to the past, a past that never makes its way into the frame. She’s almost saying: stay here, it’s all here, among these stillborn colonial houses and never-fading jungle, don’t move anywhere else at the risk of becoming lost.

What remains of this invitation, of this whimper of lazy ecstasy, of this last restraining, which was echoed one week before the invasion when Villa Lobos’s “The Little Train of the Caipira” (the essential anthem of Brazilian modernism) was played during Lula’s presidential inauguration, in the same place, in the same buildings that would soon be overrun? A hole is opened up by the voracious stabbing—stabbing the painting faster and faster in order to bring into being the magic kingdom in place of Niemeyer pale ruins.

Round 2: They Say I’ve Come Back Americanized

One of the most haunting episodes of January 8 involved the Washington Post reporter Marina Dias. As she later told a popular Brazilian podcast, during the unrest in Brasília she was attacked, wounded, and spanked by those who invaded the public buildings.4 The attack began after she interviewed an old woman participating in the attempted coup. While the old woman invoked a litany of creative conspriacy theories to legitimize her actions, Dias asked her if she was inspired by the attacks on the US Capitol building two year earlier. Disturbingly, it was this comparison that provoked the many aggressions Dias endured under the harsh sun of Brazil’s central highlands.

Indeed, much of the attention the events in Brazil have received revolves around this elegiac historical rhyme between January 6 in Washington and January 8 in Brasília, between Donald Trump and Bolsonaro, between the QAnon Shaman and the anonymous invader who defecated in Brasília’s Senate building. There was a self-evident domino effect between North and South. Nonetheless, the history of this relationship is far more complicated than a simple import from Washington to Brasília. It can be traced back to Carmen Miranda’s famous defense against those who claimed that she had come back from Hollywood Americanized.

For a very long time, samba singer and actress Carmen Miranda was the glittering and manufactured image of Brazilianity in Hollywood. In her 1940 recording “They Said I’ve Come Back Americanized,” Miranda felt the need to defend herself against the accusation that she’d left behind her Brazilian roots to become a Hollywood product. She needed to proclaim, through lyrics describing her love of the popular national dish camarão ensopadinho com chuchu (shrimp stew with chayote), her authentic Brazilianity. Nowadays Miranda is often compared to the internationally recognized Brazilian pop singer Anitta. But many forget that Anitta never needed to proclaim any authentic Brazilianity. Her breakout song, 2013’s “Show das Ponderosas” (Powerful Girls’ Show), conforms to international Anglo-American aesthetics, from its electronic melody to its black-and-white video clip in the fashion of Beyoncé’s “Single Ladies.” Yes, there is a hint of Brazilian funk in the song, but it is overshadowed by the electronic amalgamation of the Americanized pop machine. If Anitta proclaimed any Brazilian or Latin identity, it was to get out of Brazil and insert herself into international pop culture. Domestically, she was always a national rendering of the outside.

The point of this apparent detour is that by 2013—the year when, as every Brazilian political analyst would agree, Brazil’s apocalypse began—in popular culture there was no longer any Brazil to be found. The country’s experience was understood not as appropriation but as the total consumption of American otherness. It is one of the undeniable merits and legacies of Lula and the Workers’ Party government: the democratization of consumption in Brazilian society. This propelled not only economic growth but an unprecedented ten years of social well-being and a rare sense of progress in a country forever haunted by social inequality. However, 2013 obliged one to ponder the consequences of this democratization, of this incorporation of the Brazilian masses into the consumer marketplace. Because as more and more people bought Asian televisions and American fridges and traveled to Disney’s Magic Kingdom, this incorporation not only provoked a catastrophic, phobic, and criminal resentment among the elites, who thought consumption was their privilege alone; it also raised the possibility of the disappearance of Brazil. Suddenly, the shared national and communal experience was the buying of American otherness. In this light, the protests of 2013—indecipherable and enormous demonstrations the marked the beginning of the present combat—become a little bit more comprehensible. There was a general incredulity in Brazil over the “Journeys of June” in 2013. No one could understand, not even the protesters, what these acts in more than one hundred cities, rallying over two million people without any clear leadership or political affiliation, wanted or demanded. If the riots started over public transportation prices, they suddenly began to demand things like the cancellation of the 2014 World Cup in Brazil. There were fascists and anarchists in the same streets, feeling the same amazement at becoming historical again. The entire country was caught off guard by the idea that it could become historical again. I remember, at twelve years old, not yet having read Hegel, pleading with my parents to take me to a protest no matter how violent it was, because I too wanted to become part of History.

Perhaps the most famous slogan of the 2013 protests was “The giant has awakened.” The masses had opened their eyes after the consumer dream, and they wanted to know themselves. They wanted to feel that they were powerful in a way that Anitta’s hit “Powerful Girls’ Show” and the country’s fading culture no longer made them feel. But in the streets, there was no history, only a general feeling of confusion and indecision about whether what was happening was an anticipation of Carnival, or a revolution without horizon. The giant rapidly understood that no matter how awakened it was, it remained a sleepwalker, protected by bossa nova ringtones and the ahistorical tropics, where everything remains utterly unimportant in a melancholic and joyful splendor.

This explanation was not enough for many of those who went into the streets in 2013. It is no coincidence that these protests were the first to owe their organization to social media and contemporary technology. Their vacuum of justifications and demands, their refusal to remain on the margins of history, and their technological mediation became fertile ground for conspiracy theories of all kinds. In a talk given in Argentina in 2022, Boris Groys described conspiracy theories as a renaissance of medieval theology: “Conspiracy theories precisely emerge in this unclear, un-transparent space between global process and national politics, between global and local.” In this way they are similar to medieval theology, which “regulated the relationship between global God and the local individual as such, in the form of conspiracy if you want, conspiracy as a battle between God and demons.”5 Economic progress had reached the Brazilian masses in the form of consumption, but the magic kingdom, with its holy trinity of guns, KFC, and middle-class stability, had not yet arrived. In between them, there was a gap, an abyss of incomprehension, that allowed reality to be twisted into all kinds of fairy tales to justify why the magic kingdom had not yet arrived in Brazil but could be reached in seventy-two hours, with a little more burning of the Amazon. A denial of reality becomes truth not as correspondence but as revelation. In this sense, it is clear why, when confronted with the image and example of the US Capitol attack, the delusional Bolsonaro supporters in Brasília reacted with aggression and denial. The magic kingdom as history is solely theirs; it’s their destiny. Anything else, any coincidences, are masks that, in seventy-two hours, will be stripped away by truth’s arrival as a nation of skeletons.

Round 3: Our Lord of the Tires

Futurist poet Filippo Marinetti famously wrote an ode to his car. In his Futurist manifesto that was published some years earlier, the car occupied a central position as an embodiment of speed, modernity, and destruction. “A roaring motor car which seems to run on machine-gun fire is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace,” he wrote in the manifesto, already anticipating his ode. The symbol of the car in Futurist aesthetics is the point of entry into Marinetti’s enthusiastic support of the fascist movement in Italy. After all, in this uncontrollable car destined to crash, Marinetti already envisioned the fascist catastrophe; he invents fascism in this prophetic call for a confrontation with death and nothingness.

Among all the bizarre and surreal scenes coming out of Brazil in the last few months, perhaps the most strange and ungraspable is the image of a group of Bolsonaro supporters in a circle in the middle of a highway, chanting the national anthem to a single tire in the center of the circle. Perhaps they believed that in seventy-two hours this tire would gain an invincible body, be it in the form of a military tank or something worse, capable of the final invasion, the final destruction, the final negation. As Marinetti wrote in his ode to the car: “I unleash your heart of diabolic puff-puffs, and your giant pneumatics, for the dance that you lead on the white roads of the world.”6

The white roads of the world are no different than the white bones of skeletons, of total annihilation in the shattering of human flesh and difference. Roberto Bolaño, in his appallingly hilarious Nazi Literature in the Americas, invented a Brazilian Nazi novelist whose work increasingly revolved around becoming skeleton:

In The Last Word, more skeletons appear. Paulinho (the protagonist) is a skeleton almost all day long. His clients are skeletons. The people he talks to, fucks, and eats with (although he usually eats alone) are also skeletons. And in the third novel, The Mute Girl, the major cities of Brazil are like enormous skeletons, while the villages are like little children’s skeletons, and sometimes even the words are transformed into bones.7

The truth of those who invaded Brasília last week is already bones. They will settle for nothing else but this osteology.

It is worth meditating on the bones and the corpse of Di Cavalcanti, the painter of As Mulatas, as shot by Glauber Rocha in the short film Di (1977).8 Here Glauber, through a machine gun of words and images, juxtaposes Cavalcanti’s somber funeral at Rio de Janeiro’s Museum of Modern Art with footage of his paintings hung up with Scotch tape on the wall of a simple house, with popular music and sambas playing in the background. In front of the paintings, the seminal Brazilian actor Antonio Pitanga dances, as if devouring the paintings, which become mass-produced images of the masses in a trance. Meanwhile, Rio’s Museum of Modern Art remains a crypt where the totalizing fine lines of modernist architecture protect Cavalcanti’s coffin. Glauber does not care. He interrupts the funeral and removes the veil from Di’s face. He wants to devour the very beginning of Brazilian modernism; he wants to interrupt the stasis to begin anthropophagy all over again in the museum; away from the mulata’s sad glance, he wants to dream Brazil again.

Since its release in 1977, Di has been banned in Brazil by judicial order of Cavalcanti’s family. The old modernist body rots in silence among the museums and their crypts, among the indifference of Brasília’s elite and the hunger and voracity of its people. Brasília is sleepless; no Carmen Miranda samba, anthropophagical poetry, or Anitta pop hit can put it to sleep. There are no lullabies left. All bets are off. The tension in the air presages only the knockout of the somnambulist.

Clarice Lispector, “Nos Primeiros Começos De Brasília,” Portal Da Crônica Brasileira, 2018 →.

2 Thessalonians 2:7

Carl Schmitt, “Three Possibilities for a Christian Conception of History,” Telos 2009, no. 147 (2009).

See →.

See →.

F. T. Marinetti, Selected Poems and Related Prose (Yale University Press, 2013), 38.

Roberto Bolaño, Nazi Literature in the Americas, trans. Chris Andrews (Pan Books Ltd, 2010), 118.

See →.