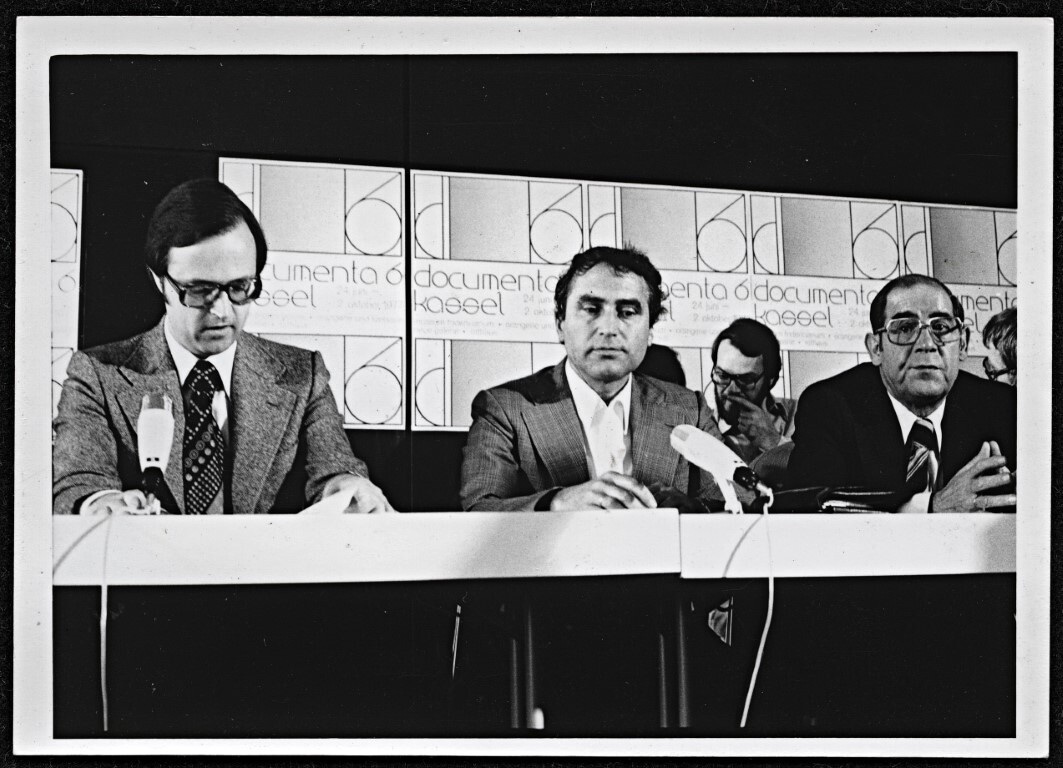

Press conference for the opening of documenta 6 in the Bürgersaal of Kassel City Hall. From left to right: Hans Eichel, Gerhard Bott, and Rolf Lucas; in the background, Wulf Herzogenrath.

Why was I gripped with rage when I realized that none of the major German daily newspapers were interested in publishing my obituary of art historian and museum director Gerhard Bott, who died on June 23, 2022, at the age of ninety-four? Hadn’t I encountered this lack of interest towards my research a little too often to be truly surprised? After all, who wants to know more about the participation of former Nazi party members in the institutional structures of the documenta exhibitions in Kassel … Gerhard Bott partook in the organization of documenta no less than four times during the 1960s and ‘70s, where he occupied important positions behind the scenes. But when he died, the media’s attention was focused on searching for anti-Semitism at documenta fifteen.

Pointing fingers at unchecked anti-Semitism by artists from some faraway “Global South” is arguably more compatible with the news cycle than the more subtle questions posed by Bott’s exemplary yet uncharismatic biography: questions concerning the networks he took part in and the still largely unacknowledged and unexplored legacies of the Nazi past, which linger on through institutional networks and mentorship relations between generations of powerbrokers in science, arts, and culture.

When Bott died he took to his grave the answer to the question of why he joined the Nazi Party as a young man. He was by no means the first to fail to speak about this—though he might well have been one of the last living Nazis to rise to a position of considerable power in postwar Germany. While German memory culture continues to be lauded for its thorough dealing with the Nazi past, old Nazis and their sympathizers have remained conspicuously silent about their involvement in the regime that worked tirelessly and fanatically on creating a racially and intellectually “pure” society according to their ideals.

Yet it’s not only former party members who have kept silent, but also their biological and intellectual children and their children’s children. This is why the biographical literature reckoning with the connections and networks established on the basis of a Nazi past is either lacking or obstructive.

The Nazi Party recorded Gerhard Bott’s enrollment under the number 10102916 on April 20, 1944 when he was not yet seventeen years old. His later career was in many ways exemplary of the construction of the Federal Republic of Germany and its art institutions. It illustrates the extraordinary opportunities of his generation, the so-called “flak helpers.” Anyone from the 1926–28 cohort who survived the final phase of World War II and was neither physically nor mentally crippled could—like Bott—obtain a doctorate by the age of twenty-three and already be working in a position of responsibility. Their Nazi past faced little to no scrutiny well into the 1990s, when the allied database based on Nazi archives was finally opened to the public and integrated into the German Federal Archives. While Gerhard Bott was young when he joined the Nazi Party, one must keep in mind that this was an active step on his way to becoming part of an elite whose continuity appeared necessary for the reconstruction of Germany.

When I found Bott’s index card in the Federal Archives in the spring of 2019, for me he was only one among many. He was part of a long list of names to be checked for my research on the Nazi past of documenta organizers. But unlike the other people on my list, Bott was still alive. In 2010 he had been appointed Hanau’s city historian at the age of eighty-three. So there was hope he would still be fit enough for a conversation. I tried to contact him, without success. What would I have asked him about? Surely about how he views his party membership today. Who did he talk to about it? Was he aware that, as a member of the supervisory board of documenta exhibitions 3 (1964) to 6 (1977), he was moving in a network that consisted mainly of former members of the Nazi party?

Sourced from my research on documenta, I can only supply splinters of knowledge, like the glimpse into networking and institutional politics offered by a letter I discovered in the documenta archive from archaeologist and cultural manager Herbert Freiherr von Buttlar. Writing to the designated directors of documenta 6 (1976), Karl Ruhrberg and Wieland Schmied, in 1974, he demanded that they give “a competent place in the collaboration to Messrs. Bode, Stünke, Blase, Bott, and v. Buttlar” lest they want to face consequences like their predecessor Harald Szeemann.

Szeemann—as Ruhrberg and Schmied were acutely aware—had been accused of misspending almost a million Deutsche marks as a result of his cutting the documenta old-boys network off in the organization of documenta 5 (1972). Szeemann not only was faced with the threat of being held personally responsible for the deficit, which loomed over his head for several years, but his reputation was also severely damaged. By naming Hein Stünke, Karl Oskar Blase, and Gerhard Bott, von Buttlar pointed to three prominent persons from the second generation of documenta organizers who stood for an interlocking of local anchoring, national reach, and international points of contact—this interlocking constituted documenta’s recipe for success. Was it a coincidence that all three had been party members in the Nazi state?

Von Buttlar—though by all accounts no party member—had previously gained notoriety in his role as secretary general of the Akademie der Künste West by reprimanding the Jewish poet Mascha Kaléko. When she refused to receive the Fontane Price in 1960 unless a high ranking former Nazi resigned from the jury, he let her know in public that “if emigrés aren’t pleased by how we handle things here” they should simply stay away.

When writing to Schmied and Ruhrberg in 1974, von Buttlar held posts as the director of the Hamburg University of the Arts and as chairman of the documenta foundation, an informal association established to raise funds for special projects in documenta exhibitions 3 to 6. Von Buttlar’s insistence apparently secured Bott a place once again: not only on the supervisory board but also in the decision-making bodies of the sixth documenta.

Bott was able to expand his network into the Rhineland with this move, as the d6 board and curatorial bodies were dominated first by Karl Ruhrberg (former director of Kunsthalle Düsseldorf and then head of the DAAD artist program in Berlin) and then Ruhrberg’s successor to the job, Manfred Schneckenburger, director of Kunsthalle Köln. After fourteen years as director of the Hessisches Landesmuseum in Darmstadt, Bott took over the general management of the Cologne museums in 1975. Before leaving this position, Bott appointed Ruhrberg as the founding director of the Museum Ludwig (1978), and then moved to the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg in 1980 as general director, a job he held until his retirement in 1993.

Without ever attaining the notoriety and high profile of Werner Haftmann—the inquiry into whose biography has so far largely fueled the scandal about documenta’s Nazi past—Bott held important positions in West Germany, governing institutions with hundreds of employees, deciding on their programs, paving the ways for careers for some, blocking others.

In my research, he came to symbolize the lack of understanding of the past and the way our society deals with it: the conundrum of silence, relativization, and looking away that still characterizes our society when it comes to reckoning with the Nazi past. Gerhard Bott remained silent about his Nazi past even after the end of his career and right into his grave, just like Karl Oskar Blase, Werner Haftmann, Alfred Hentzen, Hein Stünke, Hermann Mattern, Hermann Schaffner, Erich Herzog, Günter Skopnik, and well over a dozen other lesser-known protagonists on the supervisory boards and organizational committees of the documenta exhibitions until the 1980s.

Their avoidance of the past makes it necessary today to painstakingly reappraise their respective stances, roles, and networks. How else could we understand the resulting continuities in the way we have built institutions? How else could these issues be adequately addressed by generations of organizers, managers, and researchers to come, who don’t want to content themselves with the perennial exasperation about right-wing violence, like the murder of Kassel district president Walter Lübcke in 2019 and the racially motivated act of terrorism against citizens of Gerhard Bott’s hometown of Hanau in 2020?

The MEMO studies conducted by Stiftung EVZ (Foundation for Memory, Responsibility, Future) together with the University of Bielefeld since 2018 make it clear that there is an enduring interest in reckoning with the National-Socialist dictatorship, yet factual knowledge is fading.1

Today more than a third of the respondents to the MEMO studies reckon that Nazi politics are literally alive and kicking in contemporary Germany, yet when asked about the ways in which these continuities manifest themselves, more than half of the respondents had no answer.

Today the majority of Germans think that their respective ancestors did not support or sustain the Nazi state at all. Over a third of respondents even claim that their families were actively engaged in the resistance. While these numbers show a gross misconception of the society that emerged from German fascism, other studies point to how these misconceptions came about, from the tremendous reluctance to acknowledge that people in one’s social space were responsible in any way for sustaining the Nazi state.

The radical homogenization of the German social fabric included not only the genocide of European Jews but extended to any form of life not deemed fit for the Nazi ideal, including Sinti, Roma, and Slavs, homosexuals, and independent women—basically any politics, cultures, and identities that were deemed deviant from the social norm. If the Prussian empire preceding the Weimar state was a fertile breeding ground for cults of toxic masculinity, racism and the homogenization of society through militarism, the Nazi state succeeded in consolidating these politics, achieving an artificially homogenized society as it had never before or after existed, and whose heirs we are.

I urgently wished that Bott would speak: What insight might a clear positioning and reflection on his past have provided? Wouldn’t an honest conversation, beyond the culture of remembrance fixated on “victims” and “perpetrators,” have helped to open the social vacuum a bit, a vacuum we live in to this day?

See →.