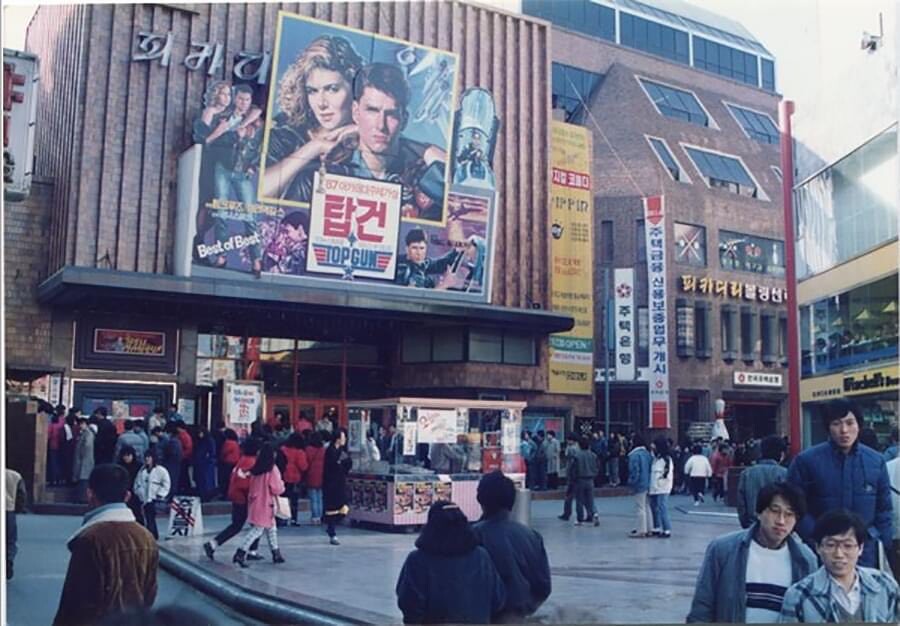

The opening of the original Top Gun, Seoul, 1987

Top Gun: Maverick exhibits how the culture industry shapes the world. The film is no mere Hollywood blockbuster but a symptomatic revelation of geopolitical reality. The arrival of this sequel to the original Top Gun (1986) is perfectly timed to the present moment, when the historical spirit of the earlier film is ripe for recall by Generation X, a cohort reared on 1980s pop culture. Not surprisingly, the nostalgic appeal of the film depends on a specific audience—“Gen Xers.” It might be paradoxical that Reaganism has subsisted beyond the rise of Trumpism, a doctrine that implies, to some extent, revenge for the effects of Reaganomics. Those who came of age under the neoliberal Reagan regime in the last years of the Cold War have come a long way through the so-called “new world order” of the post-Cold War era.

This period since the collapse of the Soviet bloc is sometimes referred to as a thirty-year peace, even though there were many “low-intensity conflicts.” The relatively amicable stability of international relations meant a decline in open conflict between nation-states; contests were mostly confined to civil war and intra-national disputes. Yet economic interests rather than a political strategy shifted the axis of state violence. Globalization, which brought forth “Global Value Chains” and accelerated the development of universal technology, has changed ways of life across the world. In this global transformation, the United States put its exceptionalism aside and served as an imperial power to sustain the geopolitical balance. The maintenance of Pax Americana was not only due to military actions but also to cultural influence on local modus vivendi. The latter could be called the establishment of a master signifier by which the axiomatics of global capitalism are sustained.

The United States, after the end of the Eastern Bloc, was perceived as a “soft power” in a geopolitical sense. The new idea of unipolar leadership influenced the understanding of US foreign policy in the post-Cold War era. Few terms have more profoundly changed the whole perspective of the US than the concept of soft power, which was coined by Joseph Nye in his book Bound to Lead. According to Nye, soft power means “getting others to want what you want” through cooperative power resources such as cultural commodities, ideology, and international organizations.1 However, US soft power only works in combination with hard military dominance over other countries. Top Gun portrays both: the soft power of the American culture industry—in particular film—and a heroic image of American hard power in action.

The economic shocks of the 1970s precipitated the end of the Cold War and the rise of neoliberalism by imposing capitalist interests over labor. The arrival of the 1980s was nothing more than the imposing of economic discipline onto political ideals such as liberal internationalism and communism. Margaret Thatcher’s adoption of TINA (“there is no alternative”), a slogan inspired by Herbert Spencer’s social evolutionism, urged the imperative of the new world order. Hollywood responded to this ideological transformation, and its aesthetic sentiment became embedded in the axiomatic (re)production of the neoliberal self. The cultural logic of neoliberalism obscured all markers of contemporaneity and gave rise to the illusion of a golden age in the past. Fredric Jameson defined this regressive invention of the past as “nostalgia for the present.”

In this way, is it possible to call the 1986 film an exercise in nostalgia in which the history of aesthetic styles displaces real history? Not surprisingly, the belated sequel is retroactively obsessed with its primary scene. What kind of past does this nostalgia imagine? Both films whitewash the concrete experiences of actual wars by focusing on the personal trials and successes of the individual. Interestingly, the original Top Gun anticipated the Gulf War, which would occur in 1990, and revealed the ideological fantasy propelling it. Americans got what they desired. There was already a space in the collective imagination reserved for the arrival of the actual war before it happened.

In this Hollywood “soft” fantasy, the failed military actions involving the confirmed facts of actual wars are romanticized, and the traumatic experiences of a shameful history disappear in the fictitious story of charismatic heroes. In the films, even the enemy aircraft were entirely fake: the planes called “MiG-28s” in the original Top Gun did not exist, and the details of Russia’s Sukhoi Su-57 in the sequel were not mentioned. Some critics affirmed that Top Gun helped the United States forget the painful experiences of the Vietnam War and bolstered American nationalism. If the neoliberal self-help story relied on the logic of nostalgia, what was its sentimental recollection longing for? The pledge of Reagan’s 1980 campaign (revived by Trump in 2016) was to “Make America Great Again.” Here, the point of the slogan is not “great” but “again”—America must be great AGAIN! This unrestrained call for repetition marks the hidden excess behind the return of Top Gun.

If you want to make America great again, two things naturally follow: that America was at one time great, and that the country is no longer great today. Nostalgia is rooted in the sense that something of value has been lost. In a Freudian sense, nostalgia is the memory of memories; its emotional mechanism is permanently distorted by an invented impression of the past. The sense of nostalgia rests on symbols, but its object is not equivalent to any original object. The displacement of nostalgic feelings aims at saving the object, and its guilty pleasure is mixed with an aggression toward the original object, or rather toward the nonexistence of this object.

Top Gun is a symbolic fiction that aims to save America’s original “greatness” in the past, rather than achieving a great America in the future. In the sequel, this hidden impetus implements a paradoxical setting in which human pilots must prove their usefulness in the age of drone warfare by risking their lives through useless dog fights. Here, the idealization of dog fights serves as the archetype of free (or just) competition. Even the original story draws from an archetype that dates back more than a century. H. G. Wells was the first storyteller to create the early ideal of dog fights in his 1899 dystopian science fiction novel When the Sleeper Wakes; the idea of a heroic pilot in air combat was born even before the airplane was invented:

Throb, throb, throb—throb, throb, throb; up he drove. He fancied himself free of all excitement, felt cool and deliberate. He lifted the stem still more, opened one valve on his left wing and swept round and up. He looked down with a steady head, and up. One of the Ostrogite monoplanes was driving across his course, so that he drove obliquely towards it and would pass below it at a steep angle. Its little aeronauts were peering down at him. What did they mean to do? His mind became active. One, he saw, held a weapon pointing, seemed prepared to fire. What did they think he meant to do? Instantly he understood their tactics, and his resolution was taken. His momentary lethargy was past. He opened two more valves to his left, swung round, end on to this hostile machine, closed his valves, and shot straight at it, stem and windscreen shielding him from the shot. They tilted a little as if to clear him. He flung up his stem.

Throb, throb, throb—pause—throb, throb—he set his teeth, his face into an involuntary grimace, and crash! He struck it! He struck upward beneath the nearer wing.2

This unconscious level of airborne warfare is the groundless ground of the melancholic nostalgia in the two films. Its symbol formation is supposed to save the original object (i.e., elite Top Gun fighter pilots in a classical sense) for the bygone greatness of America. Reagan’s catchphrase manifested a demand for repeating the enjoyment of “Great America,” which was believed to be something already lost. If you want to enjoy it, first you must create it. So then, what kind of Great America must be remade by the pseudo-historical epic? In the yacht scene in Top Gun: Maverick, the secret clue is disclosed when Pete (Tom Cruise) says, “I don’t sail boats, Penny. I land on them.” Pete is in the navy but does not know how to steer a boat because he is a pilot. This irony of Pete’s existential status tacitly unveils the material condition of “America the Great”—the United States Navy, the world’s largest and most powerful navy, which has the world’s largest aircraft carrier fleet.

The US Navy became the mightiest navy in the world during the Second World War by playing a central role in defeating the Japanese empire. After the war, the United States took over the Pacific Ocean and expanded into territories it still occupies to this day. The primary scene of Great America is fabricated by the historical moment of Asia-Pacific geopolitics after the Second World War, which dramatically replaced the Japanese promise of the Great East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. The original object of Top Gun’s nostalgia is nothing other than the American Empire that emerged on the first day of the new Asia-Pacific era. Even though the film lavishly displays the fresh charm of American values and ethics, it is undeniable that Top Gun: Maverick is the return of the repressed. In actual history, the US Navy was involved in “the colossal slaughter of the innocents” by deploying atomic bombs during WWII.3 From this perspective, it is not difficult to say that the depoliticization of warfare in the films is no accident, but an act of aesthetic complicity in cleaning the dirt from America’s history. The American dream to repeat greatness continues to wait for another Top Gun around the corner, and the culture industry is, by now, part of the nightmare.

However, another layer of nostalgia in the new film points to an ideological rupture between the original and its sequel. The follow-up to the 1986 Top Gun is, above all, about the legendary character of Pete Mitchell as a “maverick” (his call sign). On the one hand, the film shows us the success of an impossible mission led by Pete; on the other, its reflection on Pete’s life betrays the failure of the neoliberal nonconformist. From the start we are told that his is a dying breed: “The future is coming, and you’re not in it.” Top Gun: Maverick does not long for the return of the 1980s. Its sentiment is more inclined toward mourning the end of those years, the death of the neoliberal dream. Its nostalgia has turned into a crisis of melancholia that has no object anymore.

Joseph S. Nye Jr., Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power (Basic Books, 1990), 31–32.

H. G. Wells, When the Sleeper Wakes (Digibooks OOD / Demera Publishing, Bulgaria, 1899), 176.

Dorothy Day, “We Go On Record: The CW Response to Hiroshima,” The Catholic Worker 41, no. 06 (July–August 1975).