The message was trouble. A request for connection. She couldn’t accept it. She couldn’t turn it down, either. She couldn’t afford to be known to have read or received it, so she certainly couldn’t afford to keep it. But the message carriers’ passage was logged on Balloonnet’s individual balloons’ platforms. Loss, destruction—built-in redundancy handled a certain amount of that, and she’d stayed within statistical bounds when dealing with other such requests. But too many missing drones and there’d be attention, follow-up … She needed to try something different this time.

What is it that a black feminist poethics makes available? What can it offer to the task of unthinking the world, of releasing it from the grips of the abstract forms of modern representation and the violent juridic and economic architectures they support? If it is a practice of imaging and thinking (with/in/for) the world, without separability, determinacy, and sequentiality, then it approaches reflection as a kind of study, or as the play of the imagination without the constraints of the understanding. And, if the task is unthinking this world with a view to its end—that is, decolonization, or the return of the total value expropriated from conquered lands and enslaved bodies—the practice would not aim at providing answers but, instead, would involve raising questions that both expose and undermine the Kantian forms of the subject, that is, the implicit and explicit positions of enunciation—in particular, the loci of decision or judgement or determination—this subject occupies.

Affects, contemplations, stimulations, and struggles happen in and through the lap, this site that accumulates the contexts of motherhood (associated with the womb and with the bodily grammar of caring), sexual entertainment (the lap as a space where two bodies come closer through a clientele dynamic), and domesticity (the pet dog as an extension of the family sphere, a receiver of libidinal transferences, and as sublimator of privately occurring sexual drives). The lap constitutes a space at once para-sexualized—where the relation between the mother and the child, the caretaker and the cared for, takes place—and a space at the core of the unfolding of a relation of intimacy, as the lap opens itself to both male and female sexual organs, with potential physical consequences for its beholders. The significance and potential of this accumulation of functions in this space that is at once intimate and public opens itself, when the laptop arrives, to a new configuration.

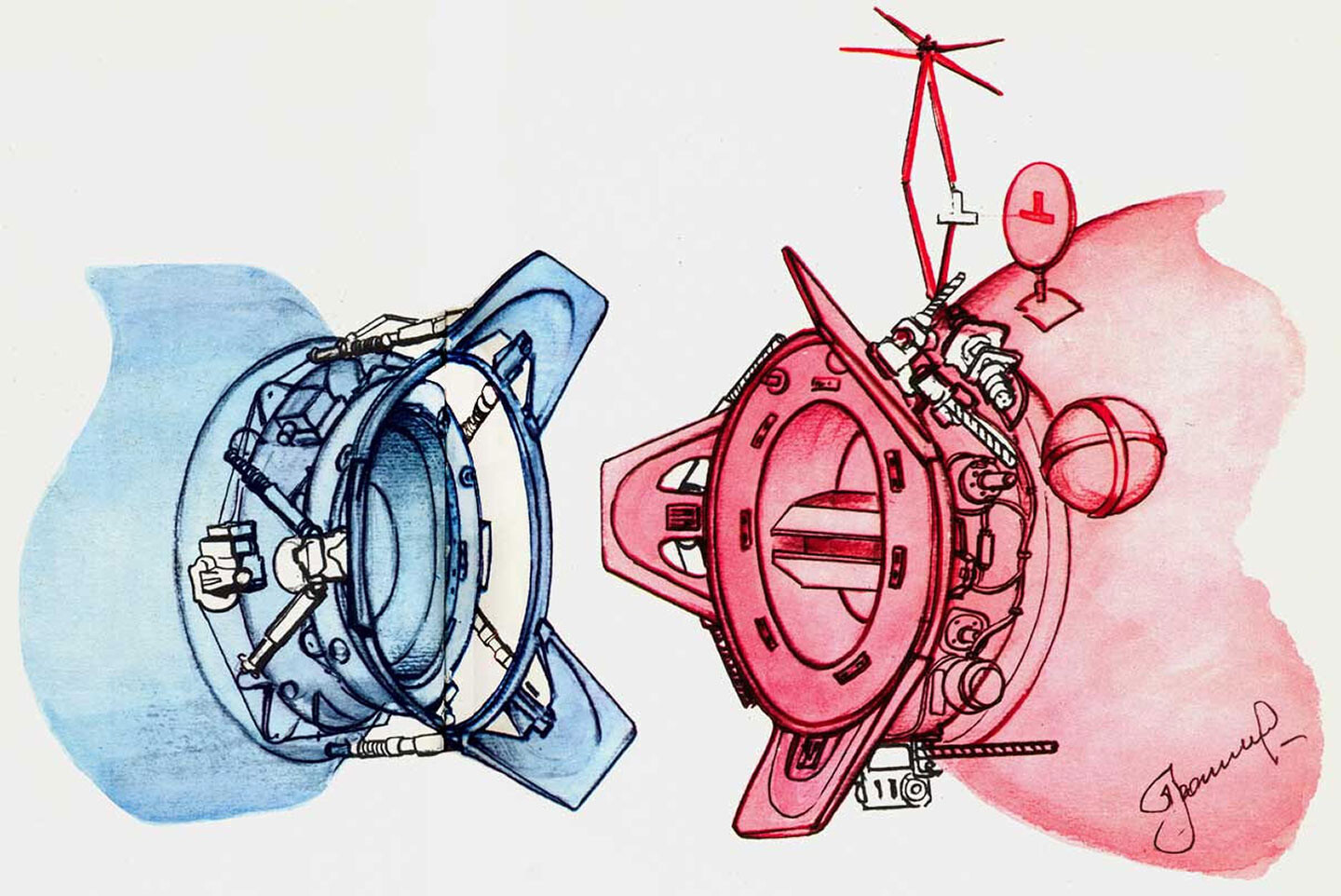

Alchemists shared the ancient Persian belief that a wise magician able to penetrate this mystery may be born only out of an unnatural, incestuous union. The Soviet engineers’ description of the union of the two space modules—the unnatural union of two antagonistic countries—resembles a mating ritual: “During the approach, a passive ship does not remain entirely passive. Its radio station provides the active ship with all the necessary information. It automatically locates its partner and, in the process of approach, rotates its docking port towards the docking port of its partner.” After two rotations around the earth side by side, the machines were to connect their docking systems, forming one white body glowing against the background of black open space.

Gender essentialism—“women’s empowerment”—overtakes any class or race discourses, which are at the core of internationalist feminist politics. “Global womanhood” becomes a category or a class in itself. Hunger is separated from class and from the failure of states to provide and distribute wealth equally. The main political aim becomes fighting hunger, without any reflection on what has caused this hunger—for example, the failure to subsidize farmers’ material needs; the historical mismanagement of water distribution, which has led to drought in many areas; the overexploitation of underground water (like in the Bekaa valley); the distribution or subsidization of fertilizers for farmers, which over many years has damaged the soil; toxic waste polluting the water; and more generally the laws around property or land ownership, which favor the few at the expense of the many. NGOs do not address this mismanagement at the state level; instead, they try to compensate for it.

“Who keeps the cube white?” is a crucial question asked by activists at Goldsmiths who are currently protesting for better working conditions and pay for cleaners at the school. For the generation of art professionals coming up now, the activism of groups such as Decolonize this Place and Gulf Labour Artist Coalition is of immense importance. The art organization Khiasma, based in the town of Les Lilas in the suburbs of Paris, aims to decolonize social relations through art by presenting challenging exhibitions and programs that pose questions about what and who produces space. Today, with neofascism acquiring greater visibility and power, intersectionality is a crucial framework for dismantling the power structures of race and gender within institutions. Practices of accountability, care, and mutual respect across hierarchical departments and job positions should be at the forefront of art institutional discourse today. At the same time, we must be wary of the appropriation of intersectional methodology by the very power structures it is intended to combat; as sociologist Sirma Bilge has written of the academic appropriation of intersectionality in the US, it can easily fall prey to the neoliberal “management of neutralized difference in our postracial times.”

Let us begin before the beginning—before the arrival of the “archon,” that is, the guardian of documents, the gatekeeper, the patriarch and the matriarch. When the undutiful daughter occupied the front room of the family home. The undutiful daughter, full of vibrant ideas not yet articulated fully, wants to provide shelter for Melly Shum, the undutiful daughter’s friend and loving aunt, who publicly declared in 1990 that she hates her job. It’s been everywhere. In the newspapers. Reporters in front of the house. On television in Teen Species. LinkedIn. Facebook. Flickr. Instagram. It’s gone viral. “Melly Shum hates her job.” On a billboard. For decades. Melly Shum. A woman of East Asian descent. Large white glasses. In her thirties. Working in an office. On her own. In Rotterdam. Pictured at work by Ken Lum. Another worker. In the picture Melly, it seems, is performing abstract labor, operating a machine to her right, maybe doing some calculations. Since 1990! Goodness. If only Melly’s abstract labor was recognized, even in retrospect—like the women trained in mathematics for the US Army’s ENIAC Project who, in the 1940s, were initially called “computers”—then she might speak again. She could speak of and against “the law of what can be said.”

The Acker I want to write into existence is not a literary one. And nor do I want to write as if there is only one Acker. There was always an Acker-field or Acker-text or Acker-web in which lots of Kathys pulsed and ebbed in and out of identity, alongside plenty of Janeys and Lulus. And not all of her identities, in life or art, were female.

Free love and camaraderie were at the core of Kollontai’s thinking, for her novels and essays describe love as a force that frees one from bourgeois notions of property. As an influential figure, a rare woman in the Bolshevik Party leadership, and commissar for social welfare in their first government, she not only set up free childcare centers and maternity houses, but also pushed through laws and regulations that greatly expanded the rights of women: divorce, abortion, and recognition for children born out of wedlock, for example. She organized women’s congresses that were multiethnic in the way the young Soviet Union practiced controlled inclusion, following Western models. At the time, these were unique measures that were soon overhauled by Stalin, who did not appreciate any attempt at ending what Kollontai called “the universal servitude of woman.”