Notes

1

Quoted in Benjamin Ask Popp-Madsen, “The Self-limiting Revolution and the Mixed Constitution of Socialist Democracy: Claude Lefort’s Vision of Council Democracy,” in Council Democracy: Towards a Democratic Socialist Politics (Routledge, 2018).

2

Butler, The Force of Nonviolence: An Ethico-Political Bind (Verso, 2020).

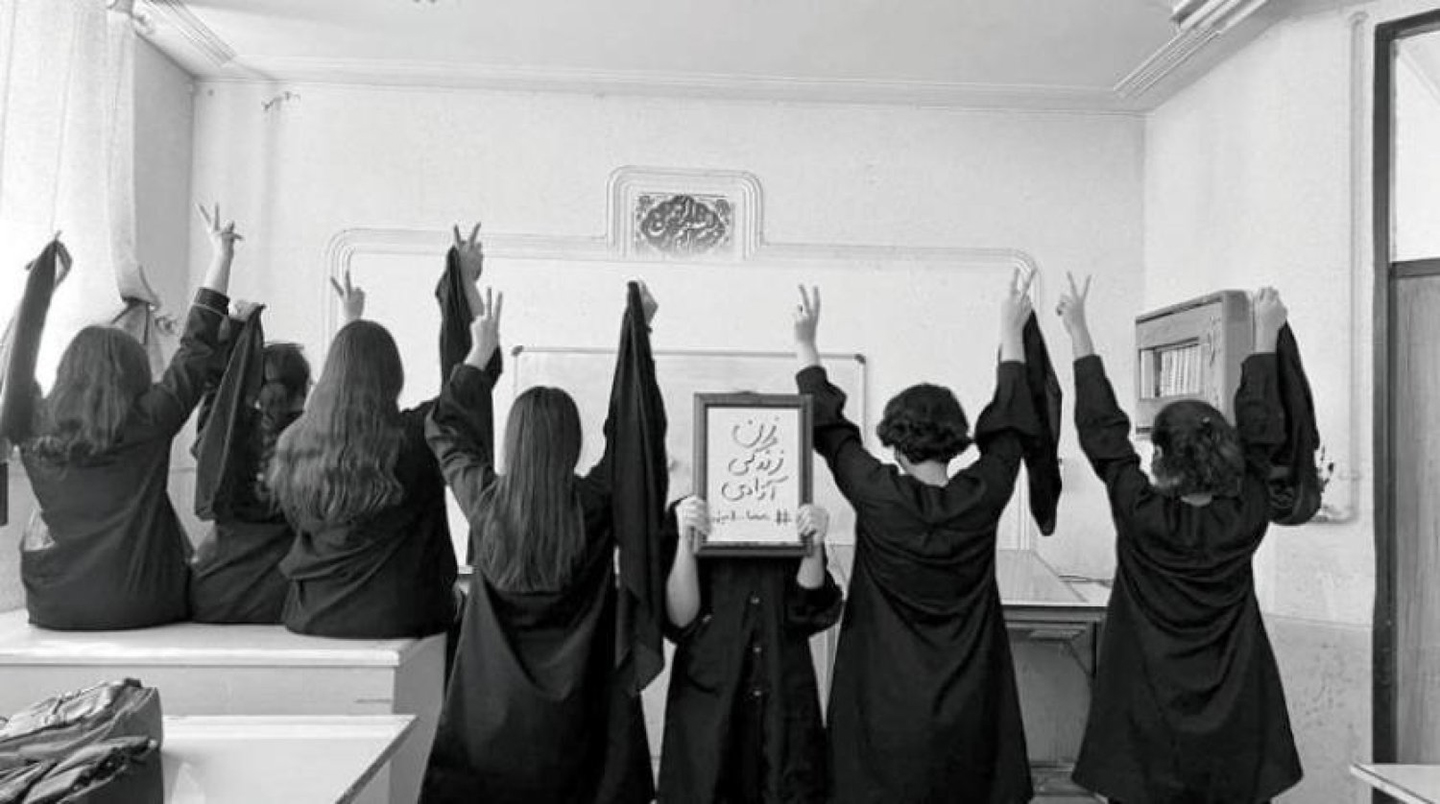

Translated from the Farsi by ZQ.

© 2024 e-flux and the author