Even if images today are flexible and manipulated, and even if passive spectacle is over and we have all become producers of images, we are always reacting against already established image-myths, and suspicion, revolts, and fragmentations only actualize their exhausted bones. But rather than attempt a media theory, here I still write to merely answer the question: Who pierced the eyes of Assum Preto?

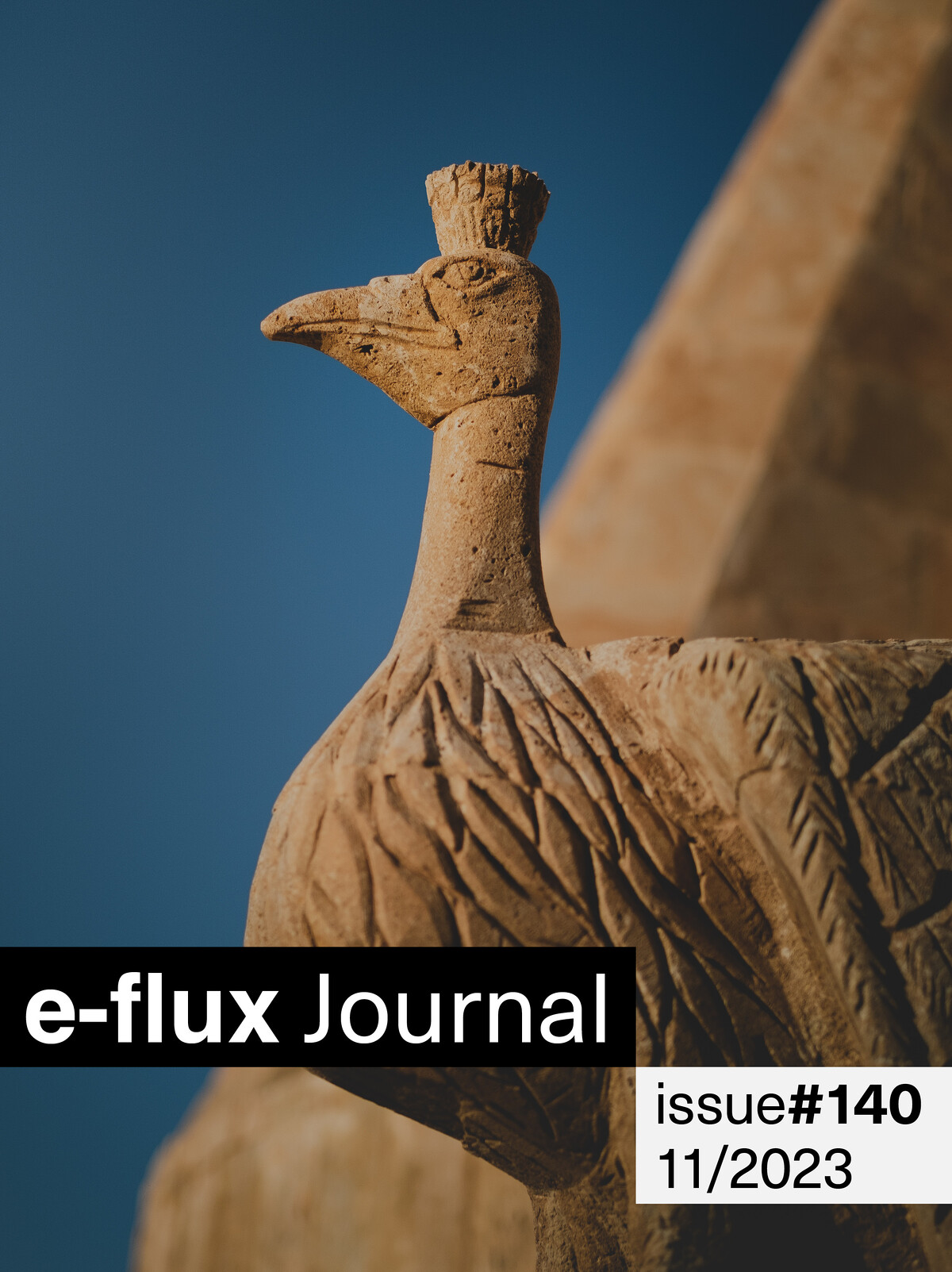

Tawûsî Melek (Peacock Angel) statue on Sharfadin Temple in Sinjar, Iraq. Photo: Levi Clancy. License: CC0.

The illogic of exclusion and exception is seductive. Perhaps we will all know ourselves better when we advertise our own place in the world by taking sides with regimes that masquerade as fixed identities and project illusory strength while actually being irreparably fragmented from within, just like we all are. The oppressed, on the other hand, know that a much larger struggle can only be sustained by distinguishing faithful from false witnesses among their own ranks as well as the enemy’s. True identity is forged by how we choose to bear witness, by what endures and grows in meaning as it is transmitted.

Thinking of Afro Asia in connection with the language of Black Power has me thinking more intently about what we can draw from the distinctions between sovereignty, self-determination, and another core Black Power term, self-defense. It has us consider sovereignty as quite distinct from autonomy; sovereignty itself is a refusal to surrender one’s humanity or claims to that which enable that humanity.

The unwieldy, internally variegated, and contested traditions that one might nevertheless nominate as black critical theory and black artistic practice, respectively, have had difficult relationships with various traditions of scholarly and aesthetic formalism (though these are, of course, hardly discrete designations). To begin with, the intellectual and artistic forms associated with blackness have typically been regarded by established traditions of formalism with, at best, skepticism.

The cumulative process of “mulatto production” constructs various no-man’s-lands within otherwise emancipatory cinema, film, and visual culture, from which certain kinds of Black female subjectivity must remain absent. While Fanon waits for himself in the cinema, at first blush Fanon’s “woman of color” has nowhere to look for her own image. Losing Ground is radical in how it breaks with this model.

Even though Hija de Perra calls for the recognition of a culturally specific conception of what was called “queer” in Latin America, throughout her work she always remained sharply critical of nation-building perspectives. Indeed, she offered a framework for a hemispheric approach that maintained vigilance against the uncritical implementation of nation-based forms of theoretical and cultural knowledge.

It would be in our collective best interest to abandon old definitions. In the same way that you discovered the truth about Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny, you now discover that there’s been a frame-up—a made-up history, an idealized version of all those things you never wanted to reflect on before and which you adored as if they were gods.

The story of AFD may serve as a reminder of alternative, pre-identitarian political sensibilities. This can be seen, for instance, in the group’s ready expression of common cause with peoples across vast cultural, geographic, and geopolitical differences, or in the way their Whitfield Street squat was a “queer” space without ever considering itself as such. Such an approach to organizing a space or collective points to a politics grounded in relationships within and across difference, and an understanding that individualized identities can function as barriers rather than a basis for solidarity.

The most interesting autotextual writing does one of two things, or even better, both: shows how selves are made, and makes room for a kind of self that otherwise barely gets to exist.