Part of what makes interviews so engaging to read is that they presume to share ideas on the fly, in a social setting and in the world. In comparison, written essays feel like constructed machines, lean and airtight with beginnings, middles, and ends. No wonder interviews, as a whole, seem a bit decadent in their procrastinatory pleasure. It’s like they catch interlocutors off guard when they should be doing something more serious. Interestingly though, the informality of speech is also a ruse, and a formal challenge for those who prefer to construct words and ideas methodically, because things sometimes spill out that wouldn’t be disciplined into more structured writing and thinking.

Cybernetic logic is always about the pursuit of a telos. So if you ask artificial intelligence to write a poem, it is always determined by an end, and this end is calculable. But in what I call tragist logic or shanshui logic we find a similar recursive movement, yet the end is something incalculable. So how can we relate back the question of the incalculable to our discussion of the use of artificial intelligence?

It was easy to turn around and see their stillness; it was impossible to catch them in motion. We were all expected to be in motion because that was how time moved and how success was measured: you were getting on an airplane, you were walking the streets of a city, you were meeting people in a bar, signing your name to things, you were racing through the night with your care and your use, presenting yourself to others, to another, everybody reading each other’s quick views—this is how I work, this is what I do—then walking off together. There was a lot of movement inside of something not moving. Inside the body waiting for the world was something radiant and silent.

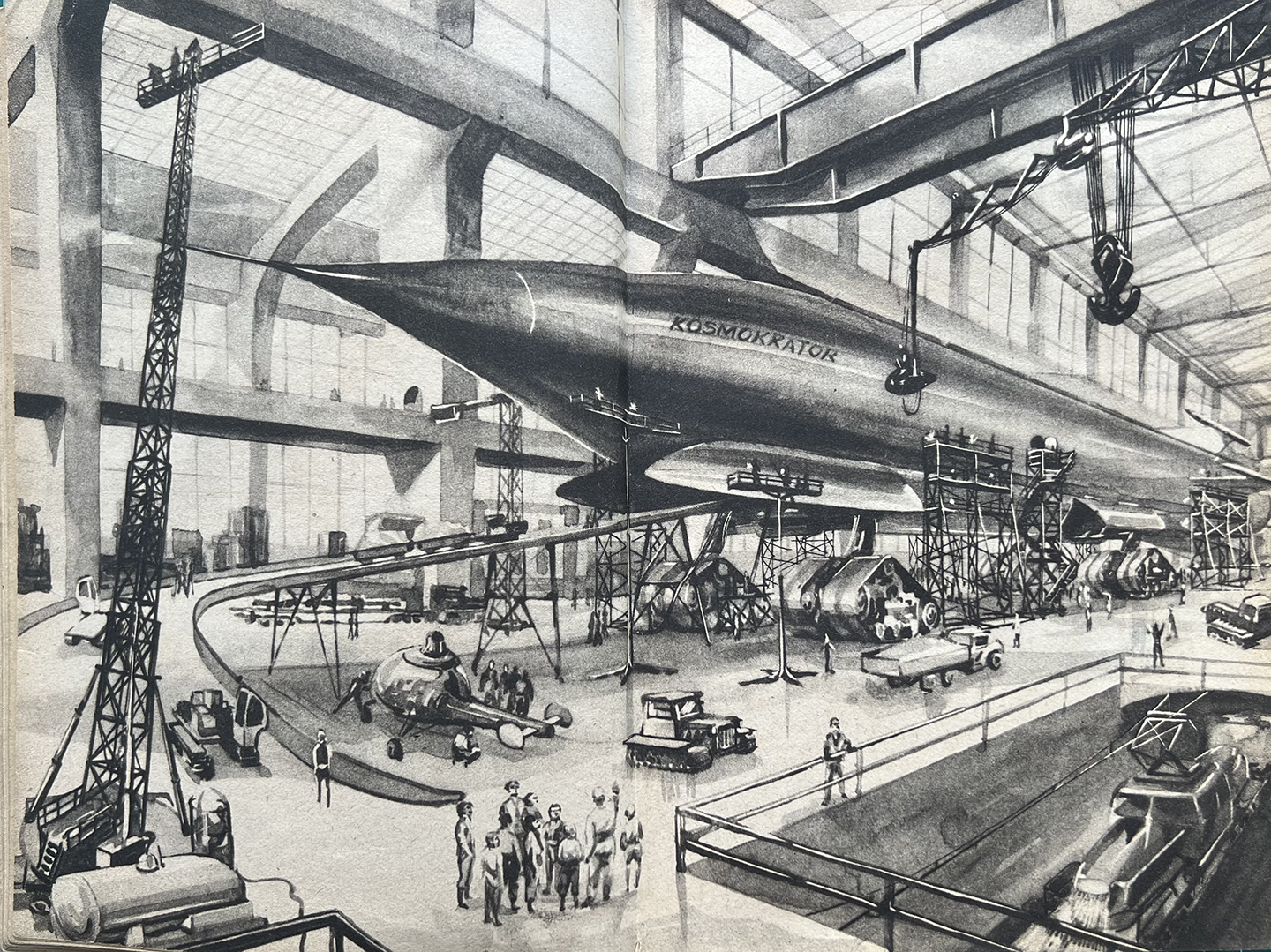

When we speak about cosmic flights and the exploration of space today, we have in mind a dynamic model of technological progress. This dynamic model of progress implies that what we’re doing now in cosmic space will be continued and further improved by the next generation, and so on. The cosmists did not believe in this model. Their questions were along these lines: Why should we be interested in progress if we don’t stand to gain anything from it? If my generation contributes something to cosmic space, how can I benefit from it? I remain mortal, and I remain eternally indentured to progress. I live now—and not in the future. If progress is defined by a dynamic directed towards the future, everyone is yoked to progress, and every generation fast becomes psychologically and physically obsolete.

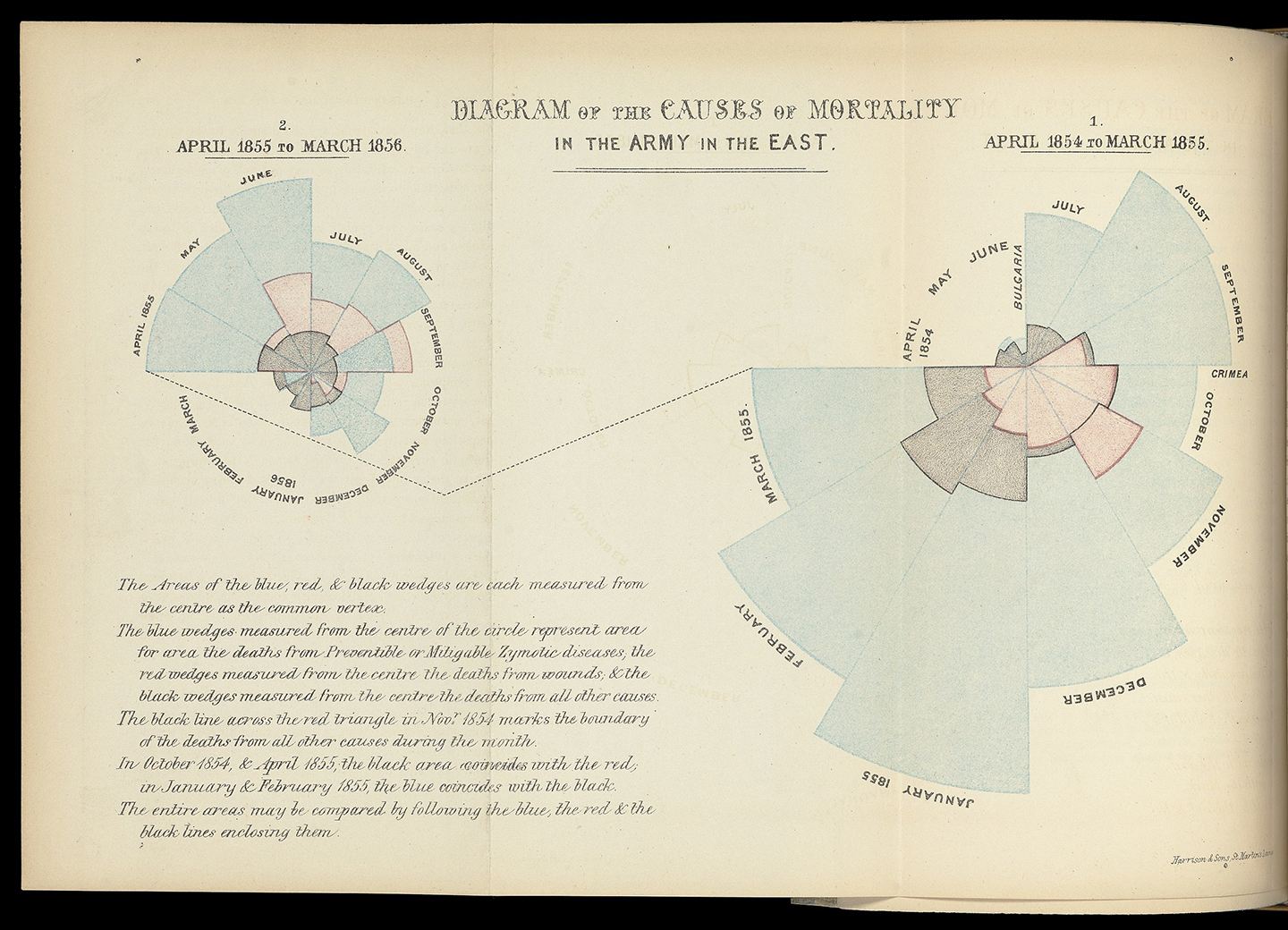

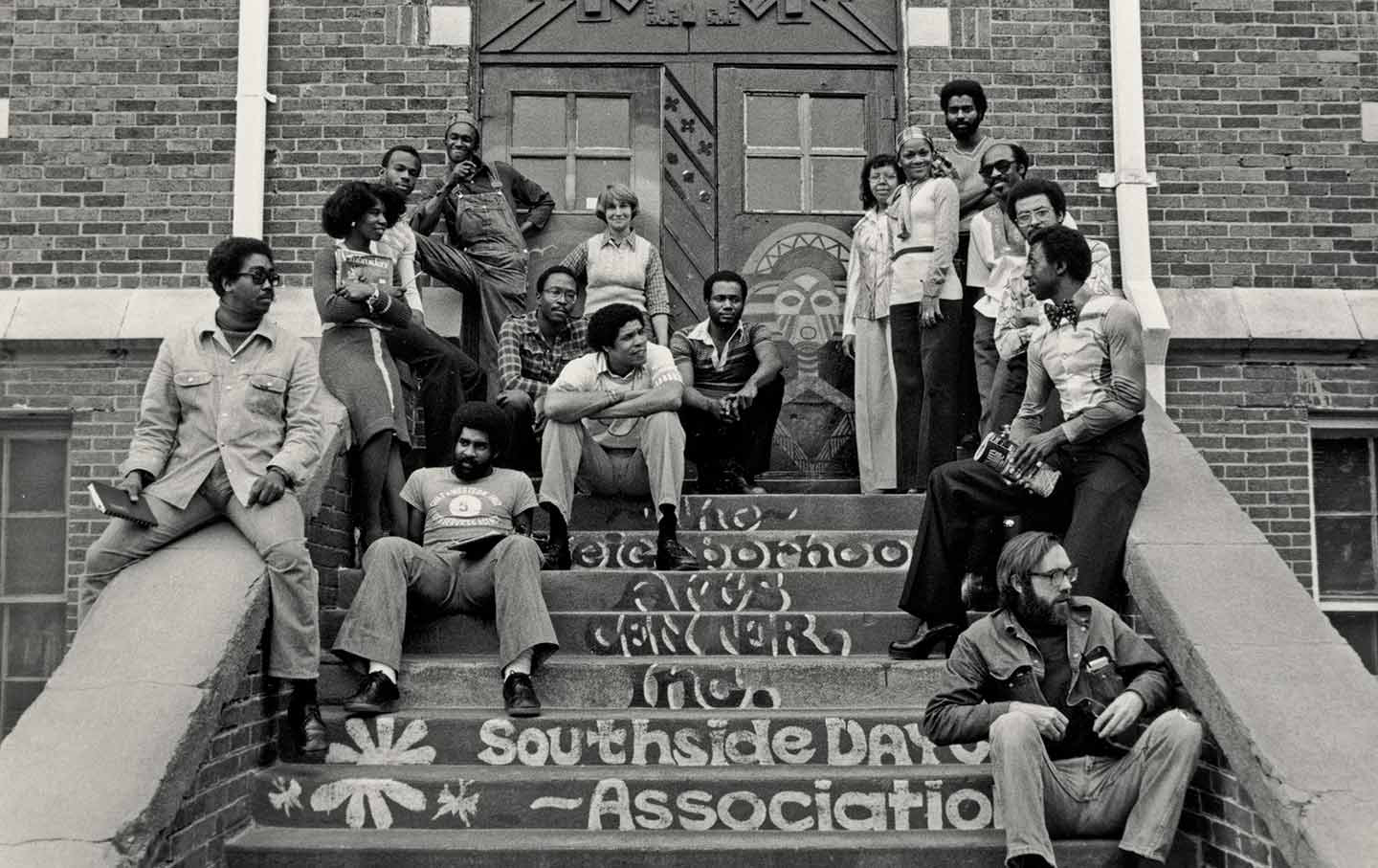

I am thinking about the spiral of W.E.B. Du Bois’s data portraits, the body as a body of facts, the touch of economics on the skin. / I’m thinking of the landscapes of extractable wealth, their labyrinths, their underworlds. / I’m thinking of Paul Robeson playing a miner onscreen, the ways he enacted or mirrored forms of burial and displacement. I’m thinking about the premiere he refused to attend. / Histories rewired, unrepaired.

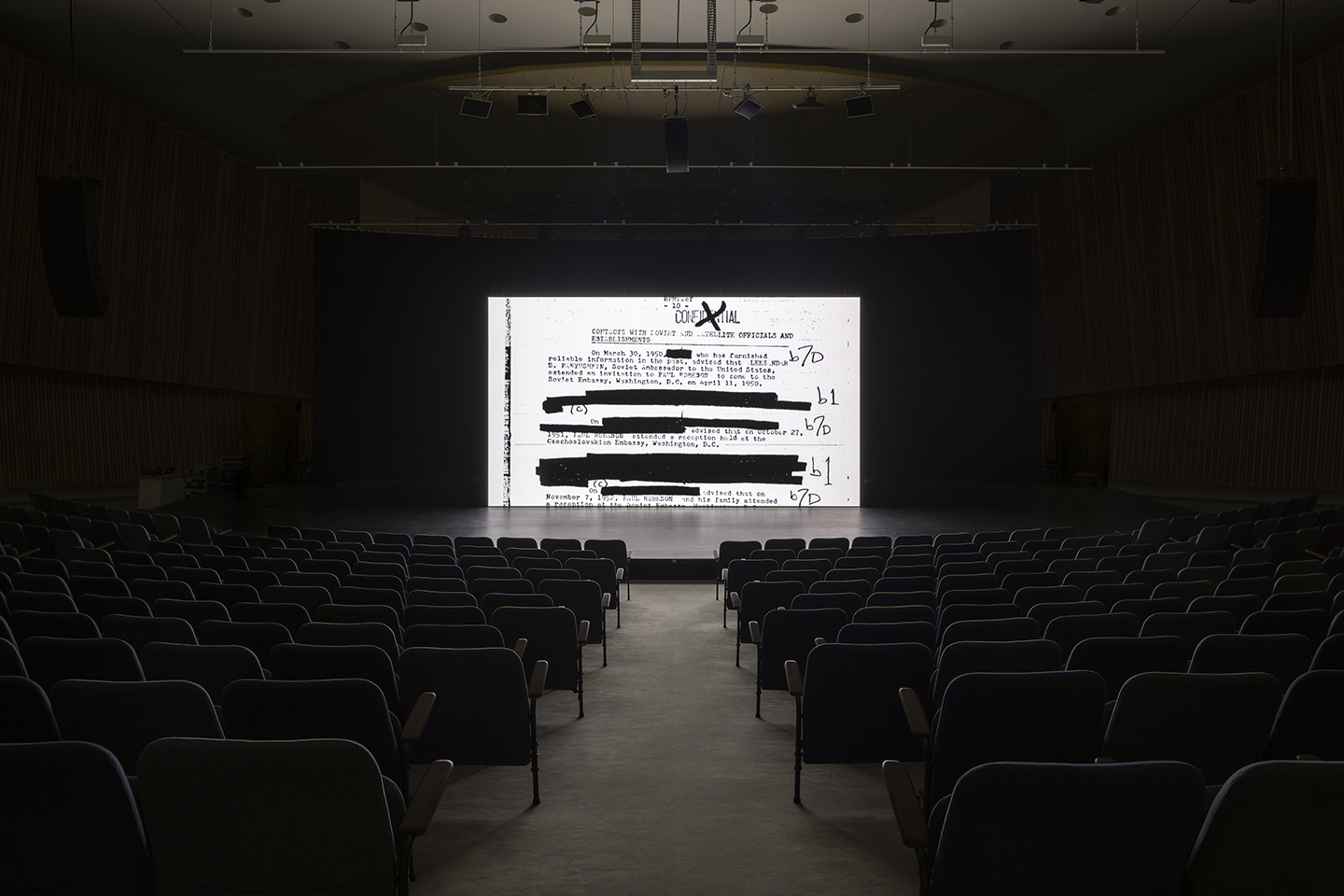

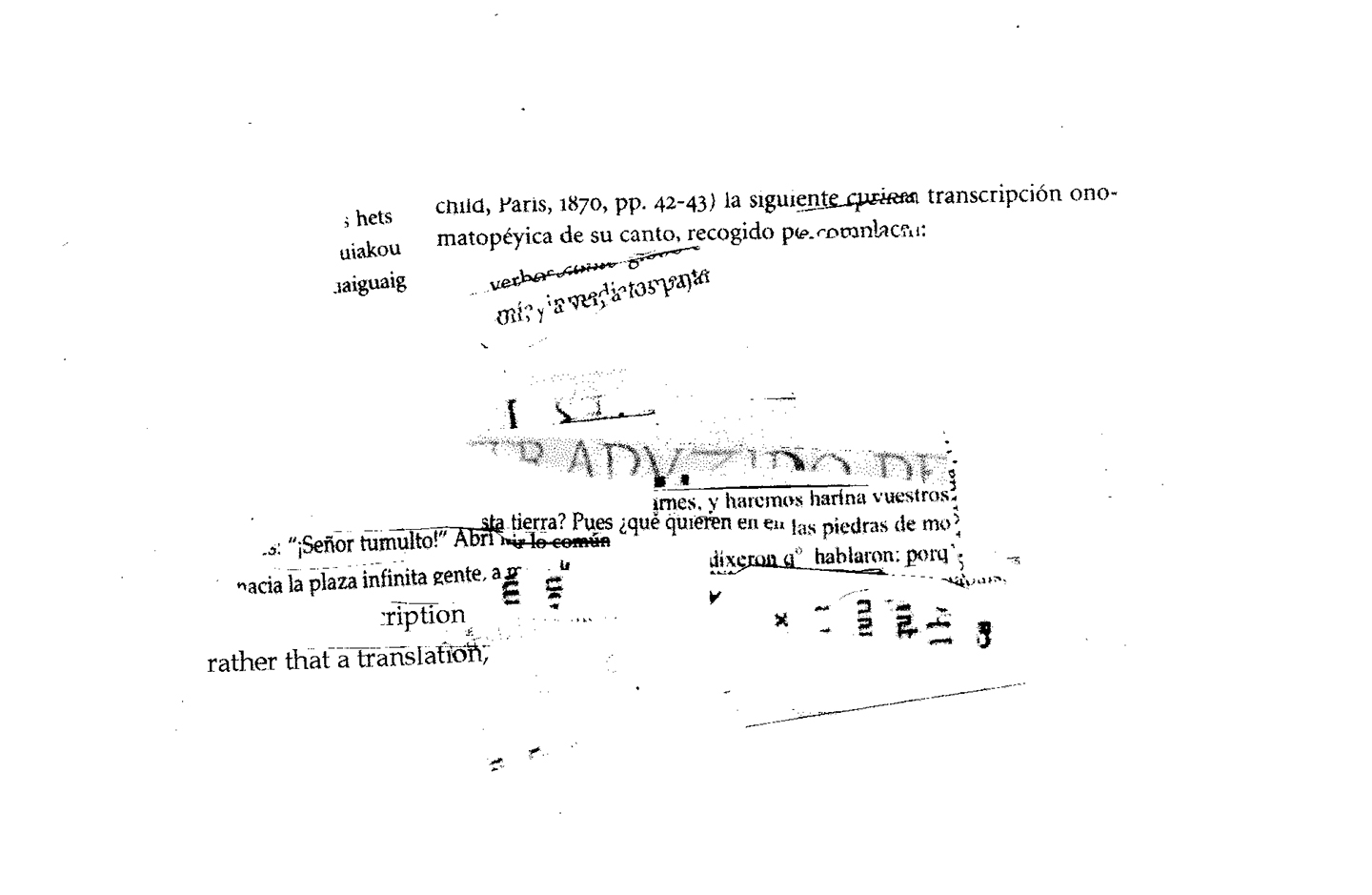

There was a structure. Things which were revealed were sealed. It was done in such an orderly fashion because, of course, these things were classified. Now they’re unclassified, but they’re still classified in a way because we don’t see all the evidence or facts that had apparently been gathered. It’s decorative to a certain extent: what is revealed and what is unrevealed, what is fact and what is fiction. So then it’s about what the spectator projects onto those files. The blackness was almost like holes within the system. Those holes tell you a lot about the failures of state surveillance, and more than anything, about the triumphs of the Robesons.

What would it mean to position the autonomy of art and art institutions in alignment with, rather than in opposition to, autonomous politics? What would it mean to take seriously Castoriadis’s notion that art only exists by questioning meaning as it is each time established, and by creating other forms for it? What would it mean to extend that to the meaning and mutability of art institutions, the places where art is made, distributed, and received? Here again, autonomy is not about separation or non-relation, but about the capacity to transform.

When we read literature / we read the budget / of the Mexican army // When we perceive artworks / we perceive the budget / of the Mexican army

I approached the whole thing in accordance with one of the enduringly interesting things about making art, which is to be annoying and unhelpful, even indifferent or destructive. Saying that, of course I talked a lot to the director of the Vorderasiatisches Museum, Barbara Helwing. And she did point things out to me. And I pointed things out to her. In some cases, it had to do with moments of intensity, and moments of speed and slowing down, and moments of wondering. What am I supposed to be looking at? Or what’s supposed to be happening here, when there’s nothing really happening? This is also what cinema can be: the feeling that I’m not sure what’s happening at this moment, but that it will become evident later on. The drive from the researchers and the director was very much towards education. Whereas I’m more interested in power, institutions, and affect.

Social scientists regularly work in study groups and research groups. They develop theses and propositions and experiments based on group work. Whereas we in the humanities are trained not to do this. We are trained to write in a single voice. It was very interesting to me last semester teaching a class with practice-of-art students called “Radical Composition.” From the very beginning, students were divided into groups of three, and each group had to create a radical composition in response to a series of assigned visual, sonic, and written texts. They were musicians and visual artists and movement artists and art historians and African American Studies students. And they all said the same thing: we’ve never been taught how to work in a group. We have our single-person senior shows. We produce our own body of work. Sometimes we help each other out, but it’s not multiauthored. We don’t all take credit.