By learning the song of the land, we may just outlast a civilization determined to take us down with it. In abandoning the universal, we may find the ground waiting beneath our feet. Seeking the guidance of the world around us, we might allow ourselves a small beginning in new worlds to come.

Chances are that in the last couple years, your life has been turned upside down by a pandemic, a war, an economic meltdown, or some combination of these. And you may feel that whatever you were lucky enough to avoid may already be on its way to you. As the coming years are sure to bring more uncertainty, maybe it’s time to prepare. Buy a small armory and move into an underground bunker? Blame foreigners or neighboring countries? Attack each other online? Let’s try instead to consider how our basic needs are met, as the individual and collective bodies that we are.

No need to exit the homosphere to core the universe. The valuable magic feces is right here, isn’t it? I have to track it like a truffle pig.

The first bite, Marcella told me, is about sharing skin and wetness. She would not eat just yet. Preparing the sago and watching her friends and family eat it had already made her feel sated.

A lack of food not only threatens human survival as such but also disrupts cultural rituals. Hunger reduces a person to their body, to exhausted flesh whose existence becomes centered around satisfying very basic needs. This experience is impossible to imagine for those living in relative comfort.

In the postwar period, bread-making companies introduced a wide array of baking improvers and began over-kneading their dough. Thus oxidized, it would whiten further. In this situation, bread-making no longer depends on its environment: in dry or humid weather the recipe remains unchanged. Bread is no longer alive; it has become a machine, just like the baker.

As a child, I never thought twice about consuming the newspaper ink and wood-pulp fibers that bled into the cutlets’ pre-fried insides and bristly, deep-fried outsides. Pulp and ink were just two more ingredients in my childhood, unmeasured but always present. Newspapers accompanied food as intimately as the background noise of mourning and uncertainty filtered through my amma and appa’s hushed tones and loud cries on telephone calls with loved ones back home.

Twenty-five million people recently went hungry in China’s most economically developed city. No one could have imagined this happening in Shanghai, where per capita disposable income is the highest in the entire country. The reason wasn’t insufficient food supply.

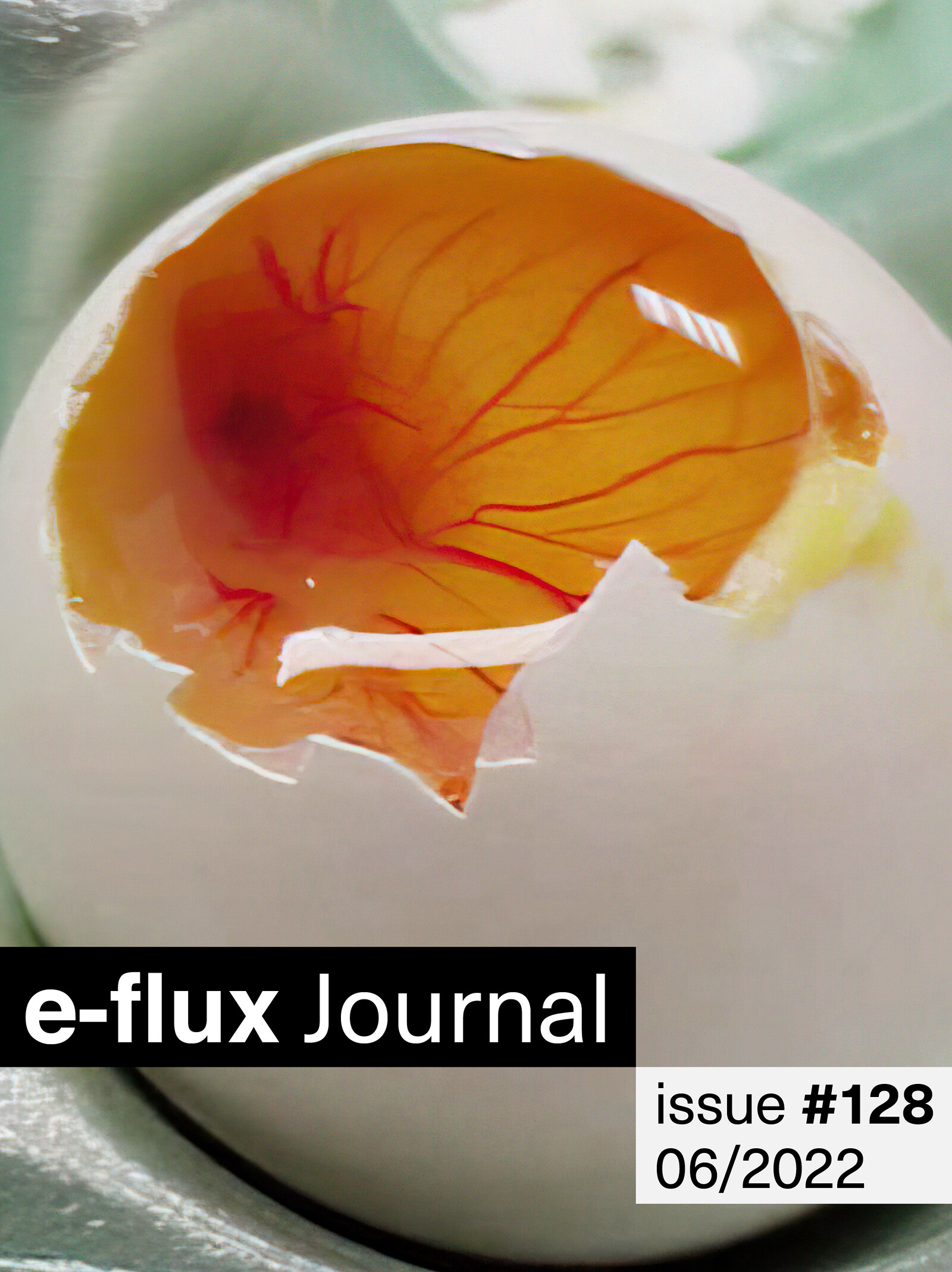

The monthly ration of eggs was reduced to the extent that eggs ended up being nicknamed “cosmonauts” because of the countdown: “8, 7, 6, 5, 4.” I remember that at some point, the personal ration was reduced to just three eggs per month. After that, I don’t remember anything.

Julia Child: Again we see that leaving behind nature in favor of culture, or “civilization,” is seen as basic to the definition of an art. But it seems especially necessary for ingestion, which otherwise is inarguably about materiality, and even need.

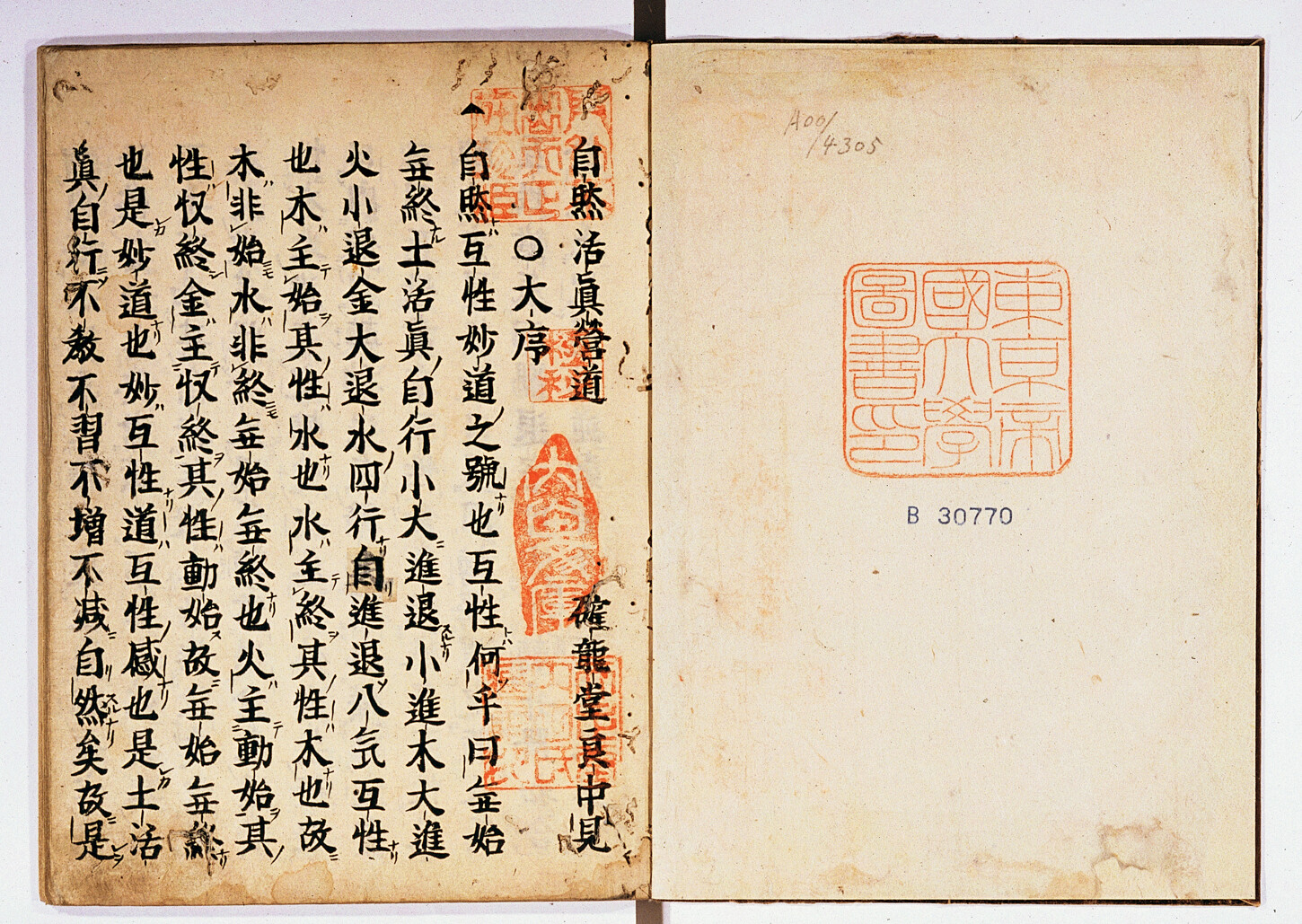

In Arabic, generous people are referred to as people of the soil—ahl al thra. The language has other references to soil as the mother of us all, but the most telling is zareea’, which means “plant” and “seed,” but is also the word for “children.” Hanan is one of the zareea’ whose life was cut short in April 2022.

The matter of food waste is rich with possibilities and teeming with microbial life. Yet food waste is most often framed as a problem, a failure, a moral quandary, an object around which to frame “good” citizenship through the yardstick of better, more responsible consumer trends, especially in the home. Loss is documented at all stages of the food supply chain; definitions and measurements of food waste vary. But mainstream emphasis is not placed on industry, policy, overproduction models, subsidies, or package design.