A premediated and unlawful act of terrorism committed either by rebels or governments can be isolated, but it can also take place in the context of war. In this case, it should be distinguished as such. Russian forces, it seems by now, were better prepared for a parade than combat. They intended to achieve victory in their failed blitzkrieg by a series of distributed terrorist acts. Their attacks on “not just selected but also random targets” were meant to seize attention and paralyze the country by shock, horror, fear, or revulsion. The occupation of a nuclear power plant—one such terrorist act—equally targets local and remote publics, opening multiple channels of negotiation or pressure to compensate for the Russian military’s disorganized invasion.

The damaged clock tower of Finale Emilia, Italy, 2012. Photo: Gianfilippo Oggioni, Lapresse/AP Photo.

It’s unclear how many people still alive today can remember feeling the strange, warm rains that fell over the riverside city of Pripyat on the Ukraine-Belarus border in late April 1986. Pripyat was built in 1970 to serve the nearby Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, dedicated to harnessing the mirnyy atom (“peaceful atom”) for the Soviet Union. For the past thirty-six years, Pripyat and a surrounding exclusion zone of inconsistent bounds bridging swaths of today’s Ukraine, Belarus, and a bit of Russia have been off limits to most human beings.

No one is asking people in Mali or Peru to live the “Russian way.” This is the difference between today’s Russia and the Soviet Union, because back in those days there were communist organizations and parties in every country of the world. They wanted everyone to live under socialism. It was a universal message aimed at the whole world. But the current “Russian message” is not universal: it is not addressed to the whole world. Second, it makes no sense to anyone. It is incomprehensible even to the Russian people, and even more incomprehensible outside of Russia, because no one understands what this Russian identity is.

The true catastrophe that has turned Ukraine into a killing field is precisely this binarism in which the West fights the very ideological monster it itself created. This war erupted not because the West should have penetrated even further into its eastern other, now called the “Russian World.” Rather, it had already penetrated too far—with the binarism of primitive accumulation (private vs. state property) that devastated this whole space and installed oligarchic rule. It’s this same binary deadlock that prevents us from imagining any end to this war beyond the dystopian vision of a fragile armistice among ruins and hatred. How much time will it take to heal the wounds of this war that divides not just two nations and millions of families and friends, but also two civilizations, two worlds? Already we hear that it may take hundreds of years. Do we have that much time?

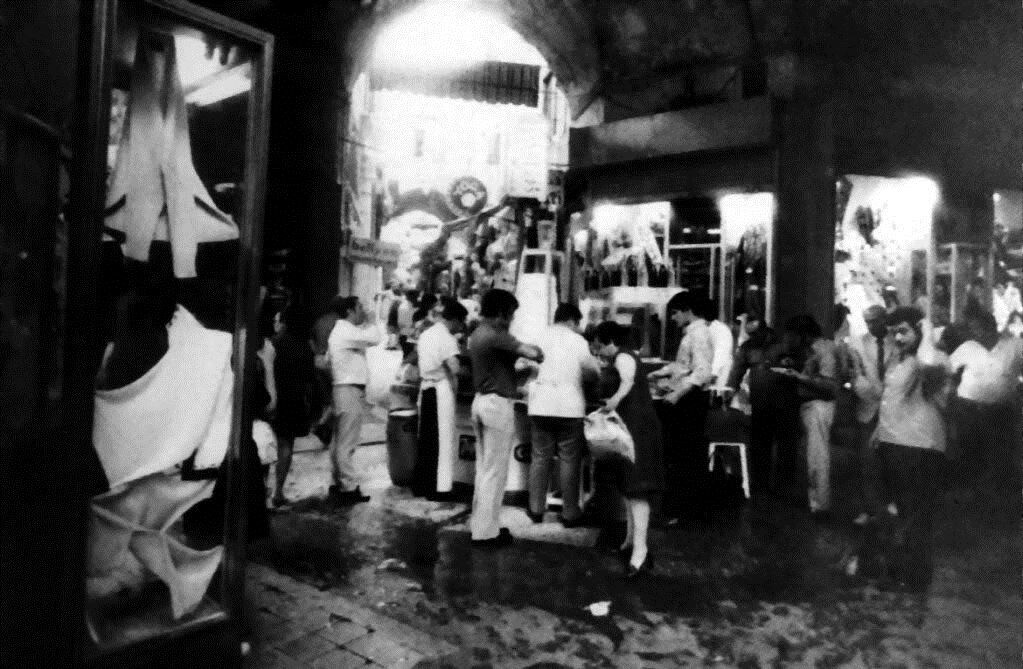

Mainstream historical accounts have long held that the sexual revolution and subsequent gay rights movements started in the 1960s in the US and Europe. What if we imagined Beirut as the heart of a queer revolution where anti-imperialist ideals and sexual freedoms are tightly interlinked? What would happen if we imagined, further, that this was an all-encompassing revolution for “the wretched of the earth”—one that sought a definitive break with Western, capitalist, heteropatriarchal ideologies and drew inspiration from premodern spiritual wisdoms? Pasolini, a colossal figure at the nexus of queer sexuality and radical leftist politics, could help us reconfigure the past along these lines and envision alternate futures.

Eternity is timelessness; it is nonliving death. Life is finite, temporary, but it is meta-nonliving. The living can see/observe the nonliving (and the living), while the nonliving cannot see either the living or the nonliving. If 2D images derived from RNA/DNA sequences are “pictures of the world” recorded by living matter, then perhaps another kind of life-form, regardless of its molecular structure, might perceive the world in a similar way. Its “pictures of the world” might correspond to those recorded and saved within RNA/DNA. In other words, if the two living forms are structurally different, having different or even unrelated material properties, they might still perceive the world in a similar way. Temporariness is the price life must pay in order to be able to see the world.

Or am I wrong to assume that the pursuit of petrification is individual, not collective? A reprieve from life and not, like the living Buddhas of Japan, an ongoing vital practice? The pain of mummification was endured to alleviate our own; do the petrified, in their own manner, unburden us through their actions?

As plastic has become so central to communications and infrastructure, plastic operates as a logistical medium—that is, a medium that sets the “terms in which everyone must operate.” Plastic determines so many of our relations, including the goods we can access, the distribution of food, access to water, medical supplies, and an infinite variety of other things that arrange and regulate the movements of people and the qualities of our lives. It is a leverage point of power, distributing and amplifying other systems of inequality.