July 14, 2010

e-flux is pleased to present an exhibition of artist books by the Croatian artist Mladen Stilinović, focusing on works produced between 1972 and 2009.

In his extensive oeuvre and through various media, Stilinović mirrors and questions the ideological signs that condition a society. Active in former Yugoslavia during the communist regime, in his art he exposed the symbols that were the strongest expressions of ideology at the time. In agreement with the Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin’s statement that “Language is the ideological sign par excellence,” the artist’s interest in language remains at the center of his activities.

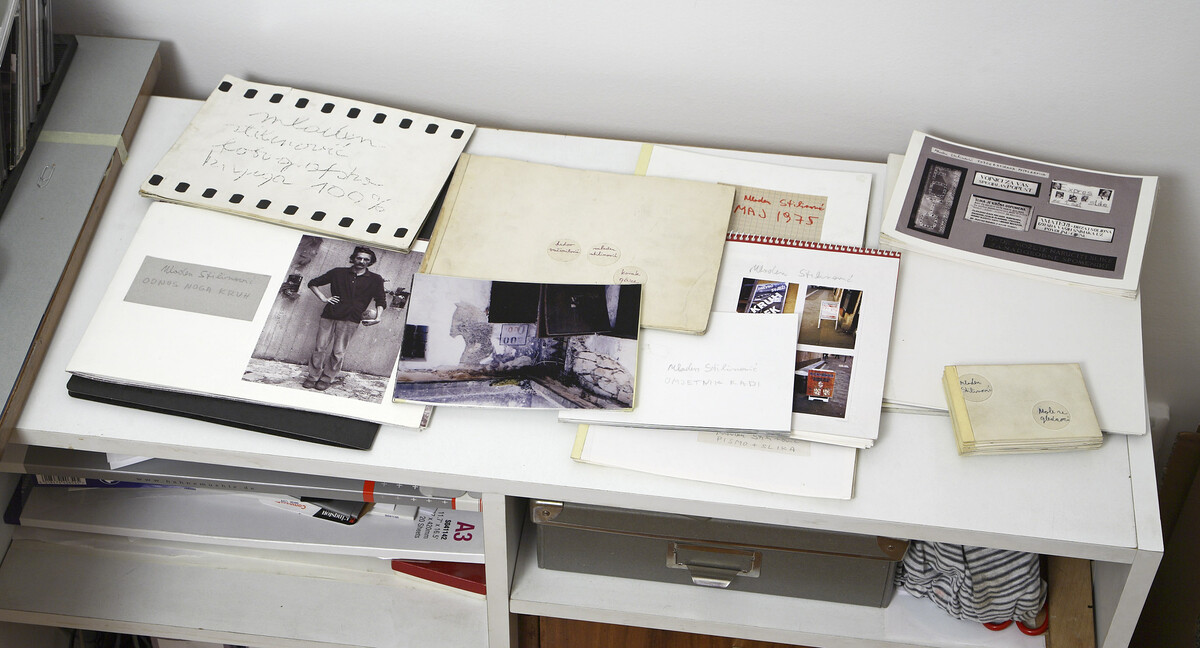

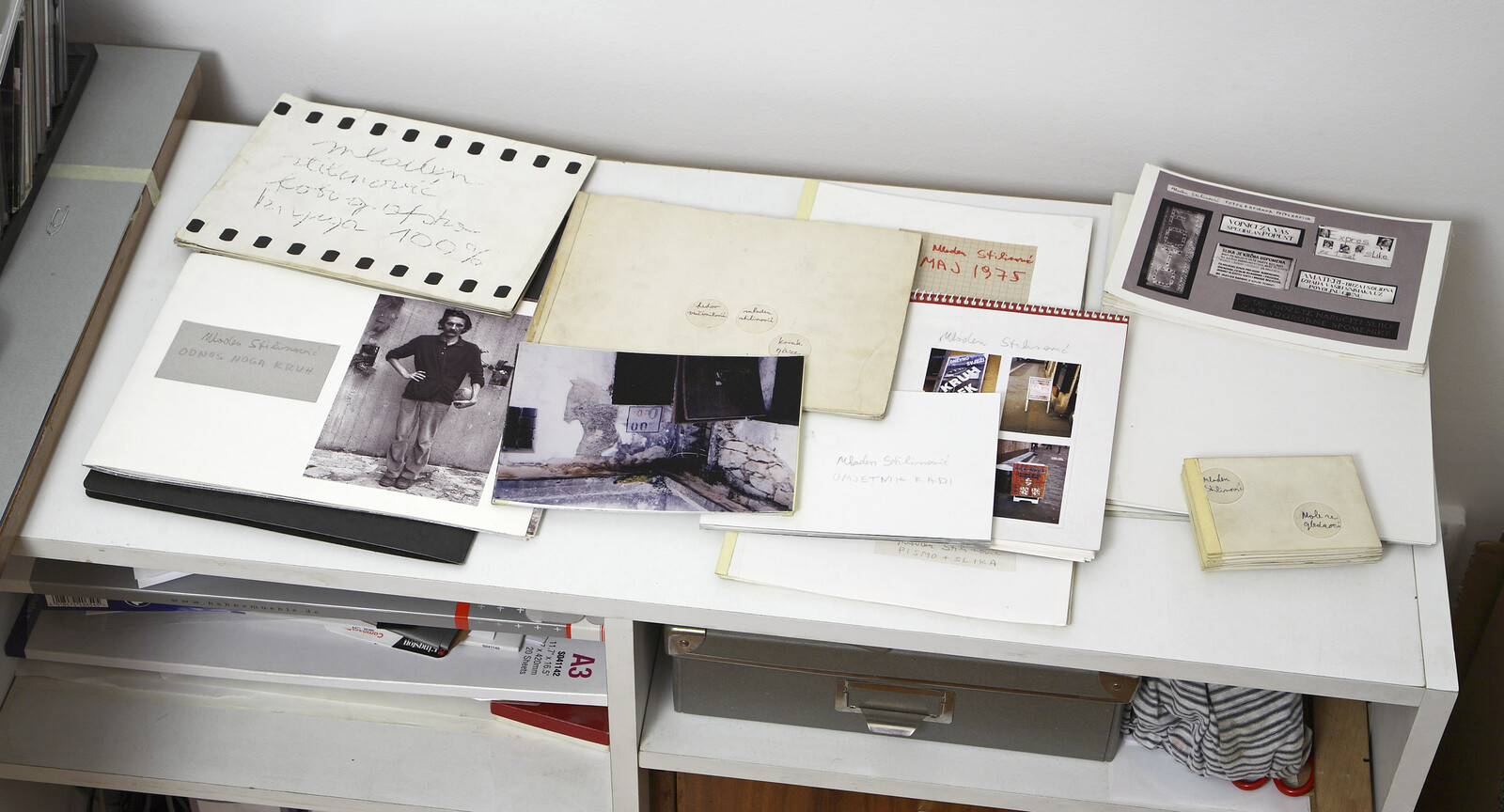

In the mid-1970s, Stilinović’s work was often shown in outdoor exhibition actions arranged by the Group of Six Artists, of which Stilinović was a member. His books were later exhibited in galleries, museums, and in the artist’s own apartment. Only a few were printed, but in connection with the exhibition at Index, Stockholm, he published an edition of My Sweet Little Lamb, an artist book from 1993. Stilinović’s early work in poetry and film led to an interest in artist books, which the artist still produces in small handmade editions using simple materials such as photographs, newspaper clippings, and writings in crayon or pencil. They can be seen as a time-based medium forming a kind of dramaturgy, or anti-dramaturgy that escapes a conventional narrative focus: if a story is present, it develops intuitively and in the mind of the reader. Often, as in My Sweet Little Lamb, a leporelo format unfolds the book into a filmic sequence of pages.

An interest in history and time can be found throughout Stilinovic’s oeuvre. With a sense of melancholia and subtle humor, his critical position points to the absurdities and rigid structures in society. His position can be seen as one that purposely insists on the freedom of art and its possibility for offering a radically different perspective. A quotation from Wittgenstein’s Tractatus used by the artist in My Sweet Little Lamb reads: “Everything we see could also be otherwise.”

One of the artist’s books included in the exhibition is entitled Artist at Work (1978). It consists of a series of images of a sleeping, or perhaps contemplating artist. In his text The Praise of Laziness from 1993 Stilinović states: “There is no art without laziness.” During the communist regime, work had strong symbolic connotations, and in his art Stilinović began investigating the relation between the color red and the notion of work. The color red held a unique position among signs in the communist state, and thus became the starting point for many of his works.

For Stilinović, the opposite of red is pink, and, seen as the color of the bourgeoisie, it also became the subject of the artist’s interest. During years of war, when the state of Yugoslavia fell apart, he produced a series of objects in white, a color representing pain and grief. After the collapse of communism, the artist directed his interest towards more contemporary hegemonies, expressed through the English language. His work An Artist Who Cannot Speak English Is No Artist (1994–96) is a well-known example.

Mladen Stilinović was born in 1947 in Belgrade and lives in Zagreb. From 1969–76 he worked with experimental film. He was a member of the Group of Six Artists (1975–79) and also ran the PM Gallery in Zagreb from 1982–91. His works include collages, photographs, artist books, paintings, installations, actions, films, and video. Stilinović has exhibited in numerous solo and group shows worldwide since 1975.

“Mladen Stilinović: Artist’s Books” is open to the public from Tuesday through Saturday, 12–6 pm at 41 Essex Street, New York.

For further information please contact taraneh [at] e-flux.com.

Reviews

“Mladen Stilinovic”, Art in America • Mary Rinebold

In 1921, working as Soviet power was being established and its principles cemented, Kazimir Malevich satired the nationalistic veneration of labor, declaring, “I want to remove the brand of shame from laziness and to pronounce it not the mother of all vices, but the mother of perfection.” In 1978, Croatian artist Mladen Stilinović demonstrated the “lazy”…

In 1921, working as Soviet power was being established and its principles cemented, Kazimir Malevich satired the nationalistic veneration of labor, declaring, “I want to remove the brand of shame from laziness and to pronounce it not the mother of all vices, but the mother of perfection.” In 1978, Croatian artist Mladen Stilinović demonstrated the “lazy” method by photo-documenting himself in various states of sleep, and pointedly titled the piece Artist at Work. Following the fall of Communist Yugoslavia in 1993, Stilinović formally expanded upon Malevich’s polemic, insisting, “There is no art without laziness.” Working at the end of a complicated but communist regime in Zagreb, Stilinović maintained optimism for a model of art production outside of what he identified in capitalism as a commerce-intiated complex of “insignificant factors.”

In spite of-or as he’d have it, because of-his preoccupation with laziness, Stilinović is prolific in a variety of media, evidenced by and extensive output of self-published, hand-made books, currently available for interaction at New York’s E-flux gallery. Initiating viewers to the show with his penciled cursive handwriting, Stilinović inscribes his name onto the wall, repeating beneath it a dozen times the mantra, “I have no time, I have no time, I have no time…” Nearby on a table, Stilinović’s staple-bound book, I have no time, repeats the statement across nearly 20 pages. On the first two pages of the book, Stilinović introduces his playful meditation on time by speaking to the reader directly, advising, “I wrote this book/ when I had no time/ the readers are requested/ to read it when they have no time.” This suggestion reflects a strategy that spans the 34 years of his book-making: wry humor that belies serious examination of the forces of regimentation and efficiency—the feeling of having “no time” for consideration, which he regards as a powerful control of various production systems. Each page of Subtracting Zeros (1993) features mathematical equations multiplication and division of the number zero; the first page of Ten Fingers (1974) opens with one fingerprint in blue ink, and adds a fingerprint on each of the subsequent nine pages. Alongside that, a 2006 book entitled BAAA begins, “I am your shepherd,” followed on the next page by “I forgot my lines,” cleverly followed by blank pages.

On initial glance, the publications have a naive appearance. But in installation, tables and chairs are arranged to oblige visitors to handle and read the books instead of merely passing by them. The content builds: one book lists the days of the week, followed by “bol,” the Croatian word for pain; an adjacent work lists the letters of the alphabet, similarly appended; another is a dictionary. Both the mundane manuals that the artist critiques, and Stilinović’s technique, strike as similarly absurd. Self-publishing, and subverting the functional operations of serialized publications, was Stilinović’s response to the Communist exclusion of unsanctioned information. Today, his methods speak to the flexibility of traditional media and distribution as it slides to conform to information technologies.

Unlike many New York exhibition openings, the Artist’s Books opening was subdued. Visitors sat at tables and paged through Stilinović’s books (those too fragile for handling were in vitrines), most of which are archival and historic. Encouraging direct involvement with archival artworks, the artist created an anti-exhibition and an anti-opening, an event that didn’t aspire to control activity or vision, and testified to Stilinović’s ethic of opposites.

—June 9, 2010