Vija Celmins’s latest show is at once an invitation to marvel at the perfect copy and to contemplate copying itself. The heavy rope that seems to hang down from the gallery ceiling is, in reality, a stainless-steel sculpture extending up from the ground (Ladder, 2021–22). Its adjunct, another piece of painted steel, Rope #2 (2022—24) sits coiled on the floor, playing its role as a fiber weave with equal conviction. The ropes, along with two other sculptures of exquisite verisimilitude, are enthralling in their own right. They also remind visitors that the surrounding paintings, which can easily register as minimal abstractions, are exercises in illusion and replication as well.

Umberto Eco once declared the United States to be a country “obsessed with realism, where, if a reconstruction is to be credible, it must be […] a perfect likeness, a ‘real’ copy of the reality being represented.”1 This cultural propensity for real fakes, Eco suggests, is at odds with the “cultured” America that produced Abstract Expressionism and modernist architecture. Celmins seems to think otherwise. “Winter” is full of Eco’s real copies, and Ladder may even be a reference to the “Indian Rope Trick” popular in magic shows. On the other hand, “Winter” is also populated with some of the least entertaining subjects imaginable: a rock, a branch, a rope. The spectacle offered by falling snow is far from the escapist entertainment represented by Houdini.

Vija Celmins began producing realist paintings of everyday objects—space heater, electric fan, envelope, gooseneck lamp—when painting was still heavily influenced by Abstract Expressionism. Celmins entered art school wanting to paint like de Kooning, “to make that great painting that […] New York abstract expressionists were doing,” but found that she became “lost” when attempting to paint in this manner. Returning to a “simpler sort of looking,” she suggested, allowed her to “bypass [her] intellect.”2 Since the 1960s, Celmins has continued to produce different versions of these “redescriptions.” “Eyes,” she says, “have a certain intelligence themselves.” Her subjects have varied—World War II battleships, ocean waves, the surface of the moon—but the desire to “look at simple objects and paint them straight” has remained remarkably consistent.3

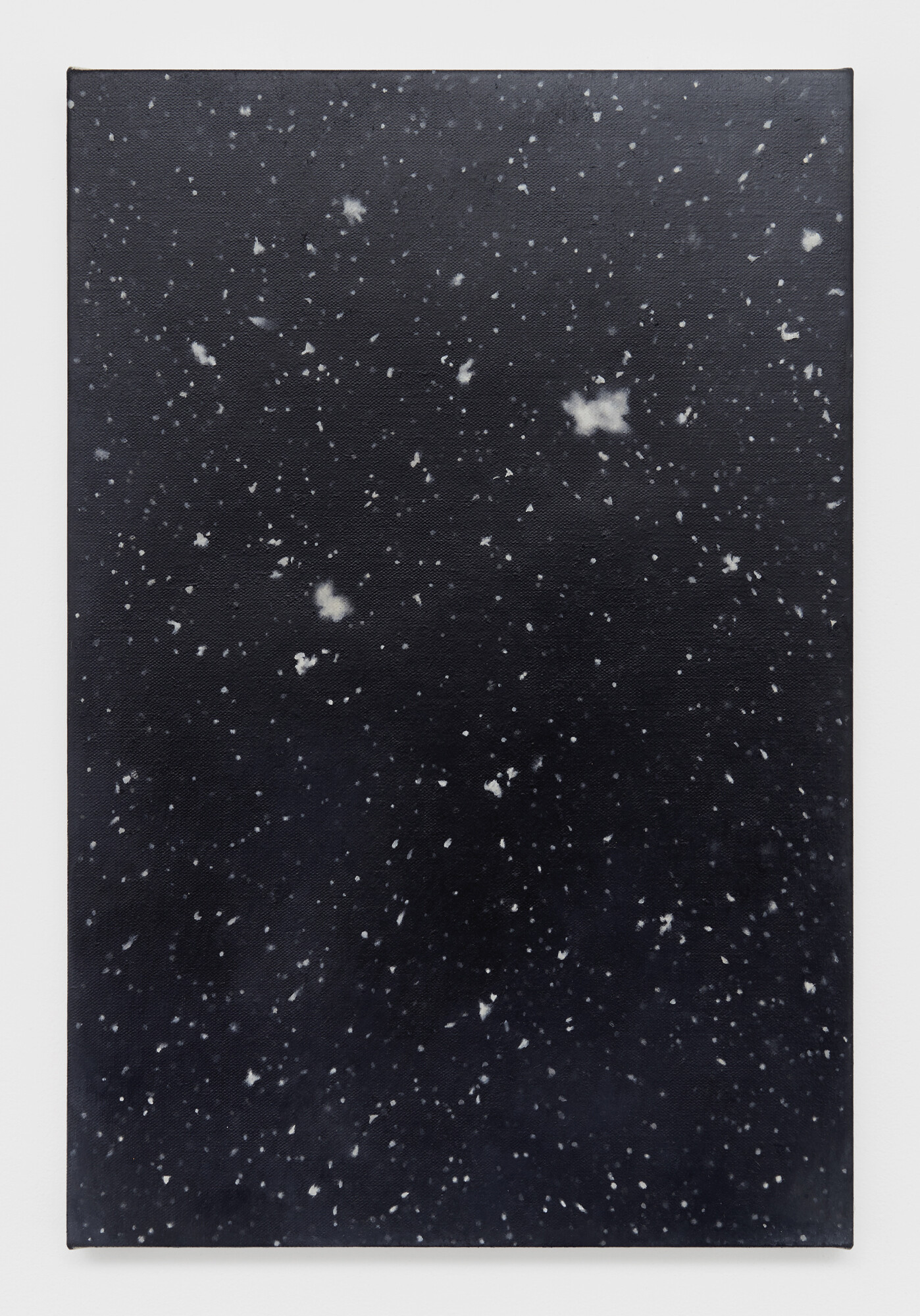

True to form, the core of “Winter” is a collection of hyperrealist oil paintings depicting snow as it falls from the sky and as it lands on surfaces like a window (Snowfall (window), 2019–23) or a dark winter coat (Snowfall (coat), 2021–23). Night sky and coat become indistinguishable from one another on the canvas despite the artist’s exactitude, pressing spectators to consider the limits of realism’s ability to convey reality. The three-dimensional work, meanwhile, invites them to a type of close-looking organized around a well-worn, even ancient, gimmick: is it real or is it fake?

It is a deceptively simple conceit. When Celmins asks whether we can tell a rock from her hand-painted bronze copy (Two, 1977/2024), she is reproducing an experience of observation as entertainment that is presumed absent from the gallery—doubly so in a gallery hung with austere and meticulous, nearly monochromatic canvases. Identifying the real among convincing fakes is an allegedly unsophisticated form of looking that Eco, for one, has reserved for pornographic holograms and Superman comic books. Celmins has absorbed this into a practice that is nothing if not serious. In doing so she has restored to us a deep visual pleasure.

It is distressing, writes the anthropologist Michael Taussig, “to keep running into the […] idea that mimesis is shorthand for bad thought—being an uninspired and unsophisticated realism in which representation is simply copying.”4 One could describe Celmins’s practice as “simply copying”, but the artist herself has argued that the copy is something that exceeds its referent, even if the subject matter is as unremarkable as a winter coat. “Art is not an illustration, it is an invention,” says Celmins.5 Copying is generative and possibly even magical. Taussig reminds us that it is the basis of “sympathetic magic, in which making a copy can (with ritual) either affect what it is a copy of, or acquire the properties of what it is copying.”

Before him, Walter Benjamin argued that mimetic ability underlies every human intellectual operation: the copy, far from being mechanical and alienating, is an expression of the very constitution of the human psyche. Which is not to say that a Western mimeticism is more “human” than other modes and styles of representation: just that our pleasure in a perfect copy made by a human hand is anything but superficial. It is the imagination of the space heater throwing out warmth, the lamp emitting light, that is central to the experience of viewing Celmins’s “objects painted straight.” The same goes for the works in “Winter” which encourage us to think we are peering out into a dark, snowy night, that a bronze sculpture could be a rock found in 1977. That it is an externalization of the universal ability and desire to mimic may be why a faithful copy is so exciting and why an encounter with Celmins’s work seems like a convincing argument for the existence of “sympathetic magic.” Reproductions of thorny branches like Cane (2023) are not sad shadows of nature or degraded forms of reality—they are reality’s enchanted double.

Umberto Eco, “The Fortress of Solitude” in Travels in Hyperreality (New York: Harcourt, 1986), 4.

“Oral history interview with Vija Celmins, 2009 February 11–October 15” Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Roberta Smith, “Deep Looking, With Vija Celmins” New York Times (September 26 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/26/arts/design/vija-celmins-review-met-breuer.html.

Michael Taussig, Mimesis and Alterity: A Particular History of the Senses (New York: Routledge, 2018), 10.

”Vija Celamins: Winter” Matthew Marks website (2024): https://www.matthewmarks.com/exhibitions/vija-celmins-winter-02-2024.