This volume announces itself simply enough. “I am here to talk to you today about the work of Ben Rivers,” begins its opening chapter, which is by Daisy Hildyard. Hildyard’s piece offers a kind of inventory of the component parts of the celebrated British filmmaker: his name “comes from a Hebrew word meaning ‘son of’ and the geographical term, as in Ben Nevis, comes from a Gaelic word for mountain peak, or cone, which derives in turn from a word meaning ‘projection’.” His last name, as Hildyard points out, requires no explanation.

Hildyard’s essay is titled “The figure on the wall,” after Henry James’s short story “The Figure in the Carpet” (1896), about a journalist becoming obsessed with the hidden meaning embedded in the work of a novelist, the way a Persian rug features a repeated pattern. It’s a subtle introduction to the inherent premise of this volume, featuring fourteen writers responding to a different film by Ben Rivers, with no obligation to describe, discuss, or even mention the work in question. Far from being exercises in ekphrasis, many of these stories depict self-contained worlds—from a fairy tale queen giving birth to a beastlike son in Marina Warner’s “Blindsight” to an extinct civilization of children depicted in Chloe Aridjis’s “Codex”—that no more than hint at Rivers’ cinematic universe. What appears as a compendium of standalone fables, essays, and poems emerges as a complex portrait of Rivers, formed around the shape of his absence.

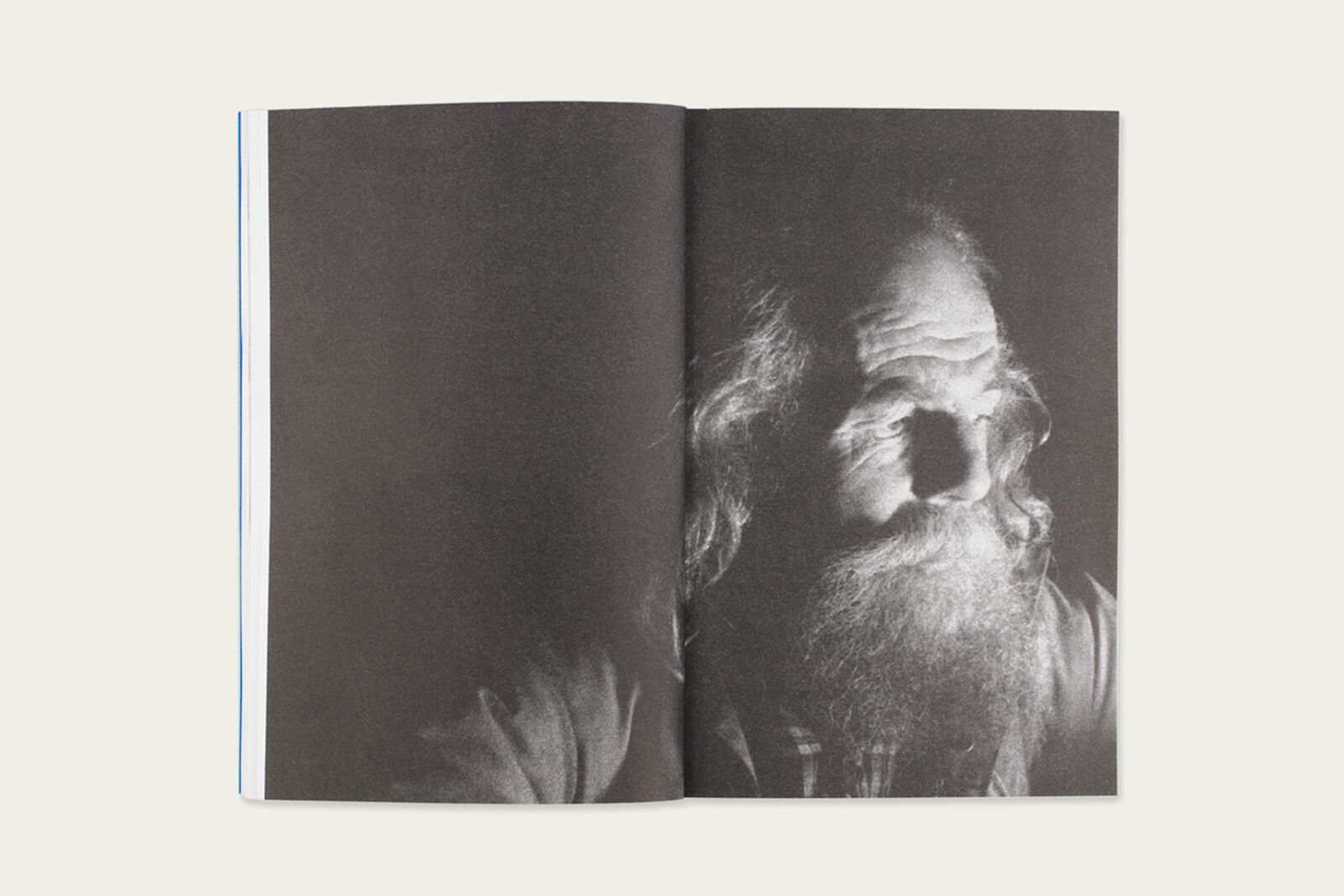

This ghostliness is fitting not just to Rivers but to his medium. Originally trained in sculpture, his films move within the genres of ethnographic cinema and documentary, all the while shading into the metaphysical, fantastic, and interior. In Ghost Strata (2019), which is also used as the name of his 2023 retrospective at the Jeu de Paume, Rivers interviews a tarot reader about the next film he is making. She replies, “It’s very funny because I would say it’s about you.” Re-encountering this episode on these pages, I was reminded of Stanley Cavell’s The World Viewed (1971): “from the narcissistic honesty of self-reference there is opened the harder acknowledgements of that camera’s outsideness to its world and my absence from it.”1 For Cavell, film had a capacity to reveal our alienation from the world and make manifest our agency in the act of perception, which could help us overcome philosophical scepticism. Rivers’s work is animated by this awareness; as Gina Apostol writes of Rivers’ “Krabi, 2562” in one of the volume’s more descriptive pieces, the film’s subject is the act of filming. “Meaning and means are the same.”

While the hidden figure in this book is Rivers, its true subject is the encounter: between artists as well as media, between material objects and their photographed images, linked here not by the particles of light that travel between them but by their attempted reconstruction in language. An encounter, writes Nathalie Légér in an essay on Ben Rivers’s film about Rose Wylie (artists regarding artists regarding artists), is “the mass of illusions and coincidences, the mass of intentions and representations that projects itself into a focal point invisible to the naked eye.” Leger’s piece appears in the middle of the volume and serves as a manifesto of sorts, a two-sided mirror, both questioning and revealing the purpose of this kaleidoscopic project: “I’m trying to capture Ben Rivers who’s trying to capture Rose Wylie who’s trying to capture – what? We can’t say, we can’t name it. She repeats. What we seek, we can’t name it.”

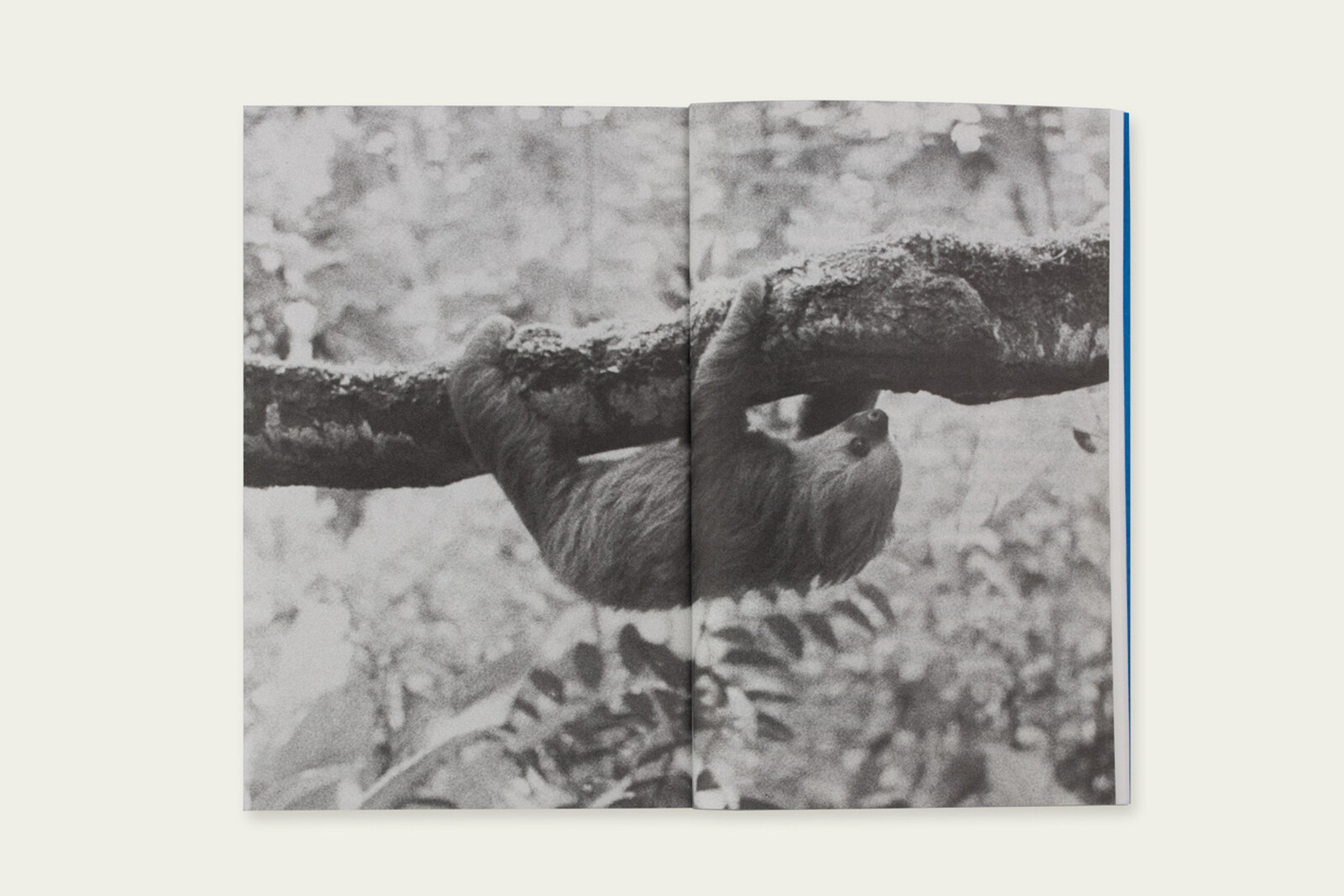

The obsession that everything is connected points always to its opposite: the fear that nothing is. A kind of instability lurks in the complex tapestry of symbols, motifs, and themes that promise to unlock Rivers’s formal and artistic universe. In M. John Harrison’s “notes for an imaginary”, an attempt at decoding a scene from Rivers’s Sack Barrow (2011) cascades into a series of questions: “How can things this close be so far away? How can things so certain be so impressionistic? How can things so certain be so tentative?” An epistolary essay by Helen Oyeyemi addressed to Rivers is strewn with interruptions by a stone acquired in a desert in eastern Georgia. The stone “simply wants you to know that it exists in this world”; it “recognises something in your art and the way of delineating the currents between people and things, occasionally halting at the question of what exactly one thing has to do with another, sometimes flowing past such constructed complications.” In “The Feminine Desert”, Xiaolu Guo narrates the parallel stories of two writers, Sanmao and Isabelle Eberhardt. “You might ask, what is the connection between the two women? Is it the desert? Is it because they were women who lived extreme lives?” She offers an answer, one that could just as well be about Rivers. “It is about belonging but not possessing.”

This points to the other central preoccupation at the heart of the collection, and of the act of filmmaking itself: a bid to belong in and preserve time. In “Never Too Late”, Iain Sinclair recounts a postponed voyage that haunts his family history, against the unforgiving finality of the past: “Narrative has no respect for posthumous sentiment and revision. What happened continues to happen, slower and slower on each cycle, until it stops: this dream called life.” In “Maybe” by Lynne Tillman, the most moving and counterintuitively cinematic of the stories, a man sitting in a corner at a party “hoping not to be seen and also wanting to be” recalls the image of a past love, now long gone. “His memories remained the same, resolute, they didn’t change, frozen with the years, and there must be something wrong about this, he felt.” In his recollection, he rewinds, pauses, fast-forwards again, with mounting incredulity: “She was fixed in him, he must be in her, she must still love him, how could that have gone.”

For such a slim, compact volume, this collection gives a richer impression of the mind’s eye of Ben Rivers than any traditional catalogue ever could. Instead, the free-form encounter brings the reader-viewer into close quarters with the artist. In this case, like a micro-almanac, the stories collected by Rivers also narrate him—and through the polyphony of voices and forms and methods, the figure on the wall flickers into focus.

Stanley Cavell, The World Viewed: Reflections on the Ontology of Film (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979), 133.