Architects, urban designers, planners, and the plethora of built environment specialists are tasked with designing for the needs of an increasingly diverse population. They implement policy and strategies in the context of change and are often required to grapple with issues of social justice and identity politics. For many practitioners, “inclusive” and “gender neutral” design is viewed as the “gold standard” for public placemaking. However, these approaches can paradoxically negatively impact many people, and can have particular concerning consequences for women and girls in cities.

Inclusive design is a process or methodology in which designers actively consider the diversity of users when designing spaces, objects, and landscapes. The aim is to ensure that as many people as possible feel the spaces to be accessible, resulting in a sense of belonging.1 Gender neutral design is an approach that does not expressly engage with gender and assumes that professionals are “impartial” and able to make “unbiased decisions” about the needs of diverse populations.2 The underlying belief between both of these approaches is that designing for a “neutral” or “inclusive” position will ensure that the needs of the majority of people will be met.

Central to this is an aim to reduce bias and to avoid inadvertently privileging one user of a space over another. The assumption is that empathy and deeper engagement with difference will follow.3 The reality may be somewhat different, however. Most designers design for the needs of people like themselves and, through the various systems of design education, practice, repetition, ritual, and reinforcement, tend to draw upon their own ideas of what is viewed as “normal.”4 While these attempts to be unbiased through neutral and/or inclusive design are well intentioned, the result is that designers often fall short and create places that are far less than inclusive, with dire consequences for women and other groups underrepresented in the design professions. As activist Caroline Criado Perez states: “failing to include the perspectives of women is a huge driver of unintended male bias that attempts (often in good faith) to pass itself off as ‘gender neutral’ and is a form of discrimination against women.”5

And the truth is, navigating sex and gender is tricky. Practitioners understandably feel uncertain about engaging with “gender” and “equality.”6 Feminist sociologist Rosalind Gill states the current context “must rank as one of the most bewildering in the history of sexual politics. The more one looks, listens, and learns, the more complicated it seems.”7 Frequently, terminology like “sex” and “gender” are used interchangeably (and therefore incorrectly). The definition of “woman” is also contentious, and, for many designers, having to navigate this complexity is outside their professional expertise.8

Sex-based language in organizational and government policy has increasingly been removed in favor of neutral terms, as well as “women’s issues” replaced by “gender relations.”9 This is most clearly seen in the shift in terminology where the phrase “violence against women” is routinely swapped out for “gender-based violence.” Gender-based violence is supposedly a neutral term, but it wrongly suggests that violence has a kind of equivalence between people—men, women, gender diverse—and leaves out the central fact that women and gender diverse people are overwhelmingly the victims and men are overwhelmingly the perpetrators. In order to address inequality, there is a need to name those that are impacted. Neutral language and gender-neutral design erases gendered experience of violence.

Despite legislation and laws aimed at preventing violence and discrimination against women, these behaviors are institutionalized. Built environment experts are reminded of this by the UN through the authorization of a clear framework for achieving women’s equality. The UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals directly addresses the need to make cities inclusive and safe by actively designing for the rights of women and girls. They focus on empowering all women and girls (goal number 5) and reducing inequalities (goal number 10).10 There are key urban typologies that demand a women-centered approach. Women and girls can feel particularly at risk and vulnerable in recreation spaces such as parks and trails, as well as on public transport and associated infrastructure networks. In addition, these places may feel safer during the day but more treacherous at night, forcing women and girls to balance their desire for freedom and agency with a perception of risk and danger. As a result, women might moderate their movements or even avoid going out after dark, and comparative research suggests that women’s feelings of safety, for example, when walking home at night, is markedly lower than men’s.11

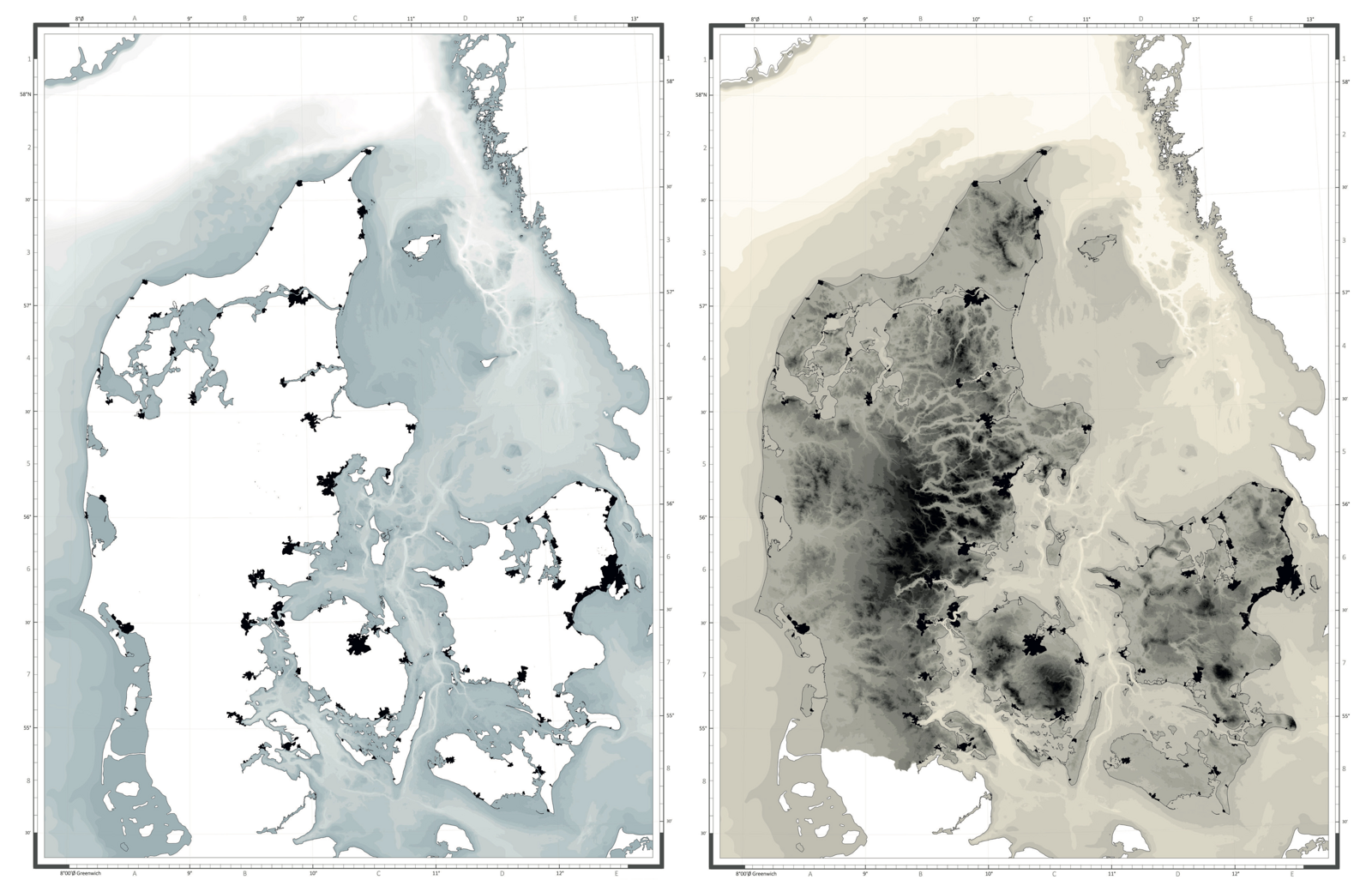

Gender sensitive urban planning and design. Diagram: XYX Lab (Isabella Webb). Source: World Bank Handbook for Gender-Inclusive Urban Planning and Design, 2020.

“Gender-sensitive design” is an alternative approach that considers the needs of women, girls, and gender diverse people and counteracts the unintended bias of built environment professionals. Gender-sensitive design responds to differences, particularities, and inequalities between women, men, and people of all genders, and aims to counter the underrepresentation of women, girls, and gender minorities in the planning and design process.12 To draw out the hidden inequalities that result from a “neutral” point of view, gender-sensitive design processes may include methods such as: mapping spatial data from women, girls, and gender diverse people about their experiences; the use of safety audits (a place-based assessment tool undertaken by local women and minoritized people); and the use of participatory co-design (where the communities who will benefit from the design are invited into the design process as co-producers).

Modes of women-centered participatory co-design. Source: Nicole Kalms (2023).

In the case of designing for the after dark experience of women and girls, engaging in a co-design process might reveal that women and girls need improved visibility and lighting. But it also might reveal that they are additionally concerned about very bright and overly lit spaces, preferring warmer and more consistent light levels.13

Make Space for Girls, a UK charity that works with local communities of teenage girls, has used gender-sensitive modes (such as co-design and data gathering) to discover what will enhance women and girls’ experiences of parks and public spaces, recognizing the role that gender plays in accessing them and the social and health benefits that follow. They note that parks can be dominated by the sporting needs of men and boys.14 As a result, women and girls may restrict their recreational use of spaces at certain times, and a dearth of other visible women and girls often means that parks feel unsafe.15

One of the findings by Make Space for Girls is that recreational swings—when designed to accommodate adult-sized bodies—are one of the most desirable facilities in a park.16 This reflects how different recreational zones and non-competitive sport facilities are preferred by girls (as compared to boys) and that swings are more often used by girls.17

Mega-Swings, Moscow, Russia by Architect AFA, Russia. Source: Monash University XYX Lab (Isabella Webb).

Mega-Swings (2019) is a gender sensitive project by AFA architects in Gorky Park, Moscow, which features interactive lights that illuminate the park and surrounding spaces after dark and incorporates color variations attuned to the seasons. Similarly, Swing Time (2014) by Höweler + Yoon Architecture is an interactive playscape in an underutilized open space nearby the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center. The rings are custom fabricated in a range of sizes, with LED lighting inside that is activated by movement, providing safety through enhanced definition of the urban space, particularly at night.

TramLab Toolkits. Source: Nicole Kalms (2021).

Gender neutral approaches to the design of infrastructural spaces, such as underpasses and public transport, have continuously failed women and girls.18 The TramLab project (2021) developed a series of gender-sensitive public transport toolkits addressing the needs of women and girls in Victoria, Australia. The toolkits were developed through engaging women’s different—and often divergent—perspectives to address complex problems of safety for women on public transport, and addressed a range of approaches including training, data collection, and communication campaigns. Its recommendations for gender sensitive placemaking all centered the importance of fostering a strong sense of belonging by tackling the physical factors that contribute to women’s fear, supplemented by women’s safety audits, co-design that involved the participation of women and girls in co-creating solutions, and gender-sensitive lighting standards.

Prior to the TramLab toolkits, the Larissa Underpass in Maroondah, Australia predicted a growing awareness and need for a gender-sensitive method for designing infrastructural spaces. The previously dark infrastructural area had been a place of risk and vulnerability for women and girls and was subsequently transformed using dynamic LED lighting, which changed along the thoroughfare and increased visibility and site lines to connect to a shared path network to a community garden. This interactive lighting assisted women and girls in managing feelings of vulnerability while passing through infrastructural spaces and is now acknowledged as a gender-sensitive approach to challenging public spaces.

All these examples of gender-sensitive interventions increase the presence of women, and, as a result, make women feel safer. While singular urban solutions will not solve women’s concerns about risk and vulnerability, well-designed and gender-sensitive approaches to placemaking will increase activity around dawn and dusk and well into the evening, helping women and girls to feel more comfortable in these public spaces for more of the day. Public placemaking responses that center women and girls can transform women’s access and sense of belonging and, importantly, will avoid designing for an imagined default (male) user. The aim should be to reduce and eliminate, rather than reiterate and reinforce, women’s inequality in cites.

Nicole Kalms, She City: Designing out women’s inequity in cities (London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2023), 120.

Clara Greed, “Making the Divided City Whole: Mainstreaming Gender into Planning in the United Kingdom,” Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 97, no. 3 (2006), 270.

Jane Rendell, Iain Borden, and Barbara Penner, Gender Space Architecture: An Interdisciplinary Introduction, Architext (London; New York: E & FN Spon, 2000), 7.

Clara Greed, Women and Planning: Creating Gendered Realities (London; New York: Routledge, 1994); Clara Greed, “Overcoming the Factors Inhibiting the Mainstreaming of Gender into Spatial Planning Policy in the United Kingdom,” Urban Studies 42, no. 4 (2005): 719–749, 735.

Caroline Criado Perez, Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men (London: Penguin Random House, 2019), xiii.

Mary Daly, “Gender Mainstreaming in Theory and Practice,” Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State, and Society 12, no. 3 (2005): 433–450.

Rosalind Gill, “Post-postfeminism? New Feminist Visibilities in Postfeminist Times,” Feminist Media Studies 16, no. 4 (2016): 610–630, 613.

The debates and discussions around definitions of woman are outside the scope of this paper. Women are not a homogenous group and differ in terms of their race, cultural background, socioeconomic status, sexuality, (dis)ability, age, and where they live, among other factors. Work in communities is about gender-diverse people too. The author encourages communities to work with a wide range of women and across the breadth of gender in their communities.

Sandra Huning, Barbara Zibell, Doris Damyanovic, and Ulrike Sturm, eds., Gendered approaches to spatial development in Europe: Perspectives, similarities, differences (London: Taylor & Francis Group, 2019), 1.

United Nations, “Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” (2015), ➝.

“Safety,” in OECD Better Life Index, 2020. See ➝.

Kalms, She City, 119.

Hoa Yang, Jess Berry, and Nicole Kalms, “Perceptions of Safety in Cities After Dark,” 83–104, in Lighting Design in Shared Public Spaces, ed. Shanti Sumartojo (Milton: Taylor and Francis, 2022).

“Make Space for Girls,” 2022. See ➝.

XYX Lab and CrowdSpot, “YourGround Victoria Report” (Melbourne: Monash University XYX Lab, 2021), 108–111. See ➝.

L. Van Hecke, et al., “Public open space characteristics influencing adolescents’ use and physical activity: A systematic literature review of qualitative and quantitative studies,” Health Place 51 (May 2018): 158-173.

Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris and A. Sideris, “What brings children to the park? Analysis and measurement of the variables affecting children’s use of parks,” Journal of the American Planning Association 76 (2010), 89–107.

Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris and Camille Fink, “Addressing Women’s Fear of Victimization in Transportation Settings: A Survey of US Transit Agencies,” Urban Affairs Review 44, no. 4 (2009): 555; Gill Matthewson and Nicole Kalms, “Unwanted Sexual Behaviour and Public Transport: The Imperative for Gender-Sensitive Co-design”, 59, in Advancing a Design Approach to Enriching Public Mobility, eds. Selby Coxon and Robbie Natter (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021).

Framing Renovation is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Faculty of Architecture of the University of Ljubljana within the context of the 2023–24 LINA Architecture Program.