That’s a Very Large Number—A Commerzbau

April 20–November 24, 2024

The Icelandic Pavilion at the 60th International Art Exhibition—the Venice Biennale opens this week, presenting That’s a Very Large Number—A Commerzbau by Hildigunnur Birgisdóttir. This uncanny exhibition, curated by Dan Byers, features an intriguing selection of new sculptures and installations, which animate the strange relationships formed between us and our world of mass-produced objects.

Hildigunnur Birgisdóttir is known for her nuanced practice, which examines the global systems of production and distribution and the bizarre lives of the products they create. Her work calls attention to the objects that exist at the periphery of our vision, often the throwaway accessories of material culture: packing materials, price tags, signage and systems of display. She looks for the beauty in these objects, which have been shaped through countless aesthetic decisions, material limitations, production conditions, moral codes, deals, desires and mistakes.

That’s a Very Large Number—A Commerzbau, fills the gallery space with the artist’s appropriations of the materials, products and language of mass production. Birgisdóttir creates an immersive environment, inspired by the tradition of the “Merzbau”, pioneered by German dada artist Kurt Schwitters. Schwitters began using the term “Merz” in his work, after discovering a fragment of newspaper printed with the end of the word “Commerz”. She reintroduces the “com”, creating a “commerzbau” from commercial fabrications and castaways of commerce.

Birgisdóttir playfully subverts expectations of beauty, value and utility within the framework of an international art exhibition. Entering the pavilion, visitors encounter what appears to be a “white cube” gallery space, however, the walls which should be pristine, cold white are painted the faded “white” of old plastic light switches and electrical cables. A wall installation, made from a recycled floor panel from the Biennale Architettura 2023, has been adorned with logos of the firms, foundations, corporations, and vendors whose products and services made the pavilion possible, making clear the hidden commercial systems involved in exhibiting at a global art event. The installation surface features holograms printed by a firm that specialises in holographic printing for banknotes, making the wall twinkle with over 100 logos.

Offering an experience that explores how objects bond to us and communicate with us, two small plastic sculptures made from the control panels of a home printer and a refrigerator blink incessantly, going in and out of sync with each other. The blinking that signals a paper jam or that you have left the refrigerator door open, with each sculpture unexpectedly producing hum-rattle of a cell phone vibration, triggering the modern-day human instinct to instantly reach for your phone. Through the window of the pavilion, visitors may be distracted from the new view of the canal by an outdoor LED screen, live broadcasting the changing advertising content from a small part of a highway-side screen on the outskirts of Reykjavík.

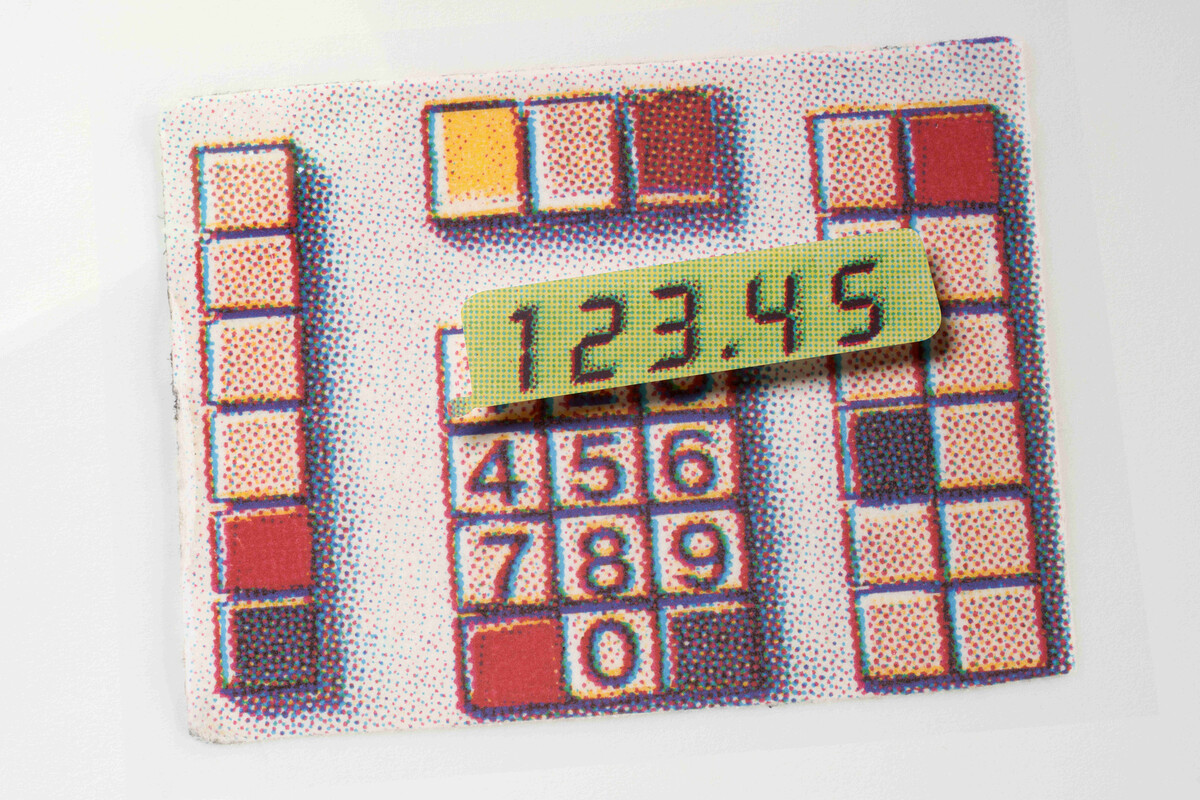

Small plastic toys made for dollhouses have been scanned, brought to human scale, and reproduced by a German firm. The sculptures capture the toys’ strangely smooth surfaces and simplified forms, designed to only communicate as much information as needed to make their function clear. The sculptures are accompanied by a pigment print adorned with a sticker, depicting a very large number captured from the screen and keyboard of a toy cash register which inspired the title of the exhibition. The artworks invite viewers to consider why these mundane, everyday objects are reproduced as teaching instruments for children, instilling consumer desire from a young age.

Large relief sculptures embellish the pavilion walls, made from the latest developments in sustainable fabrication. Produced by a Dutch firm, one sculpture is made from recycled jute coffee bags, the other from recycled denim, which has been moulded into shapes of the small, cheap packaging, that are found protecting the products that we intend to purchase. The artist’s work reflects the tension between the personal pleasure to be found in our world of material objects, but also the consequences of a world full of these objects.