Sa kabila ng tabing lamang sa panahong ito / Waiting just behind the curtain of this age

April 20–November 24, 2024

Artiglierie in Arsenale, Venice, Italy

Arsenale

Venice

Italy

info@philartvenicebiennale.net

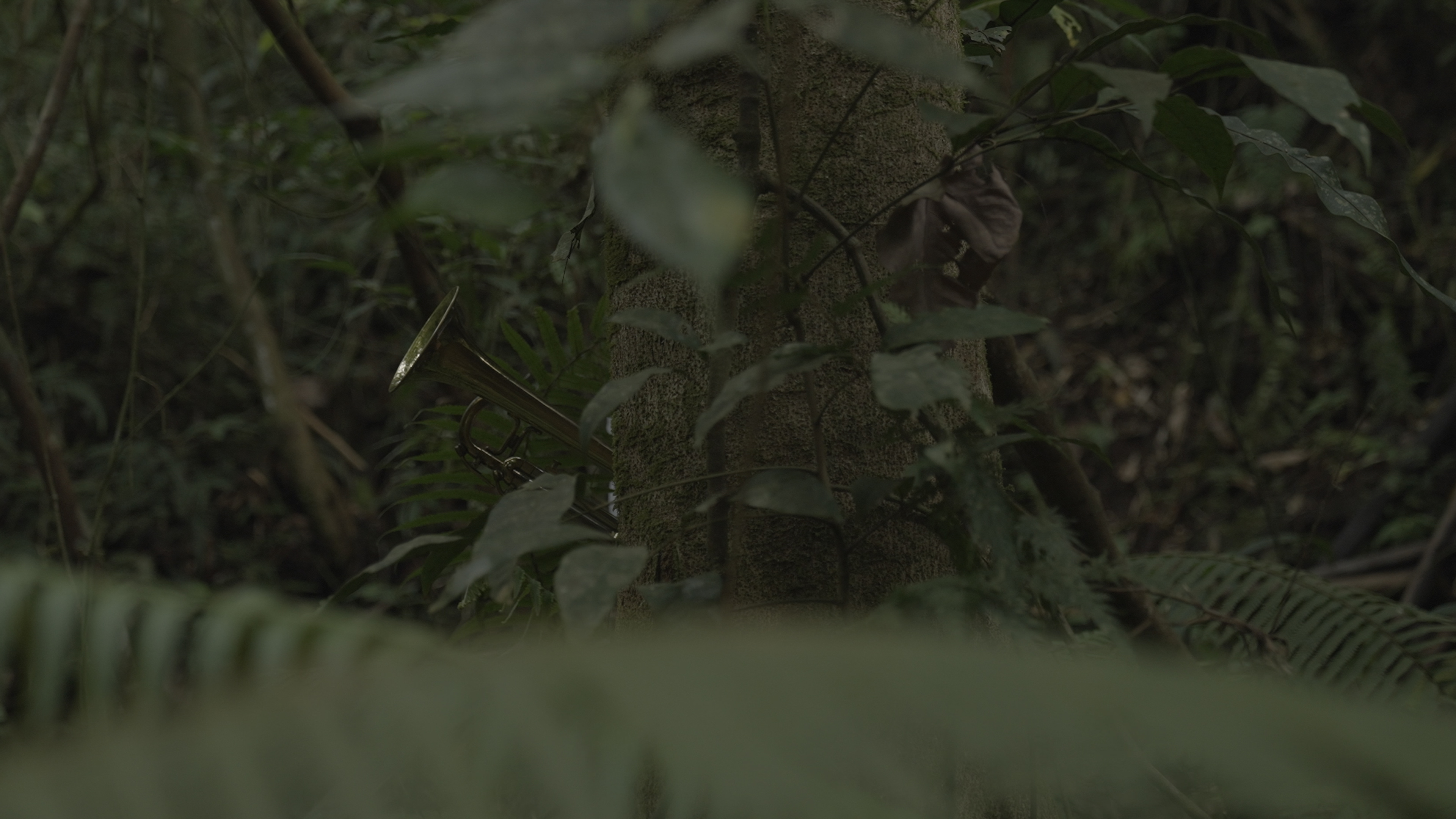

Sa kabila ng tabing lamang sa panahong ito / Waiting just behind the curtain of this age is a scenography of textile, soundscape, and stone sculptures that offers a theater of the mystical. A solo presentation of the artist Mark Salvatus (b. 1980) curated by Carlos Quijon, Jr. (b. 1989), the pavilion expands on the artist’s research around Mt. Banahaw, a three-peaked forested mountain noted as an exceptional setting for discourses involving millenarian developments and mystical speculation. It is located on the boundary between Laguna and Quezon, and Lucban, the artist’s hometown.

The pavilion’s title is taken from Apolinario de la Cruz (known as Hermano Puli), a lay preacher born in 1814 in Lucban who founded in 1832 the Hermandad de la Archi-Cofradia del Glorioso Señor San José y de la Virgen del Rosario. The Cofradia was a popular religious formation, the membership of which was exclusive to native men and women (i.e., excluding Spaniards and mestizos). Puli’s attempts to have the organization legalized failed as the colonial authorities found such an exclusion suspicious. Because of its continued operation even after being denied legal status, the Cofradia’s activities were deemed subversive by the civil and ecclesiastical authorities.

In anticipation of the encounter with the Spanish military, in what has been considered the “Tayabas rebellion,” Puli delivered one of his most rousing proclamations before the Brotherhood’s rebel frontline and declared that the “abrupt events” that were about to transpire “can be anticipated by the faithful through certain signs.” As historian Reynaldo Ileto annotates: “Apolinario was probably pointing to these when he advised the cofrades always to be aware of the ‘meaning of the times.’ Victory is ‘just behind the curtain of this age’.” The historian David Sweet considers the rhetoric that propelled Puli’s rebellion as “proto-political,” an understanding of the possibility of social change emanating from an “other-worldliness” and an understanding of reality as “magical as well as instrumental.”

Puli’s imagination of a threshold, a passage or a way through, alludes to a “crisis of futurity" from which emerges a millenarian or postmillennial time. It is a shift that finds resonance with what critic Gayatri Chakraborty Spivak delineates as a shift from a global agency to a planetary subjectivity. Rather than “continental, global, or worldly imaginations" that are based on discourses of evenness or commensuration, “the planet is in the species of alterity…[t]o be human is intended toward the other.”

Mt. Banahaw has become an exemplary site for mediating distinctions between the real and the uncanny. It has become a sacred place for a host of mystical and religious sects and cults. It has also become an important post for anti-imperialist and anti-colonial movements, such as The New People’s Army, the military arm of the Communist Party of the Philippines. Furthermore, it has played an important part in vernacular accounts of speculative cosmologies, such as the existence of extraterrestrial life forms, which purportedly have chosen the mountain as a refueling stop. In all this, Mt. Banahaw offers a mystical lifeworld of vitality and renewal that these formations tap onto.

Through a newly commissioned video work, a mise-en-scène of fabric panels and fiberglass boulders, and a reconfiguration of an existing work, Salvatus explores the ethno-ecologies of Mt. Banahaw—how the surrounding more-than-human world shapes and are shaped by cultural imaginations. It weaves together Salvatus’s ongoing research on the vernacular histories of Mt. Banahaw and Lucban, convened from family archives, popular history, and mythical motifs. It looks at several trajectories of millenarian renewal that converge in Mt. Banahaw as mystical and ethno-ecological topos: from a revolution that aimed to encourage the native folk to find their own idiom of religious discernment, a history of marching bands and musicians and their place in a postcolonial regional modernity, to Salvatus’s very own practice of assembly and salvaging that situates us in this shared mystical world, animates in us a planetary political spirit.