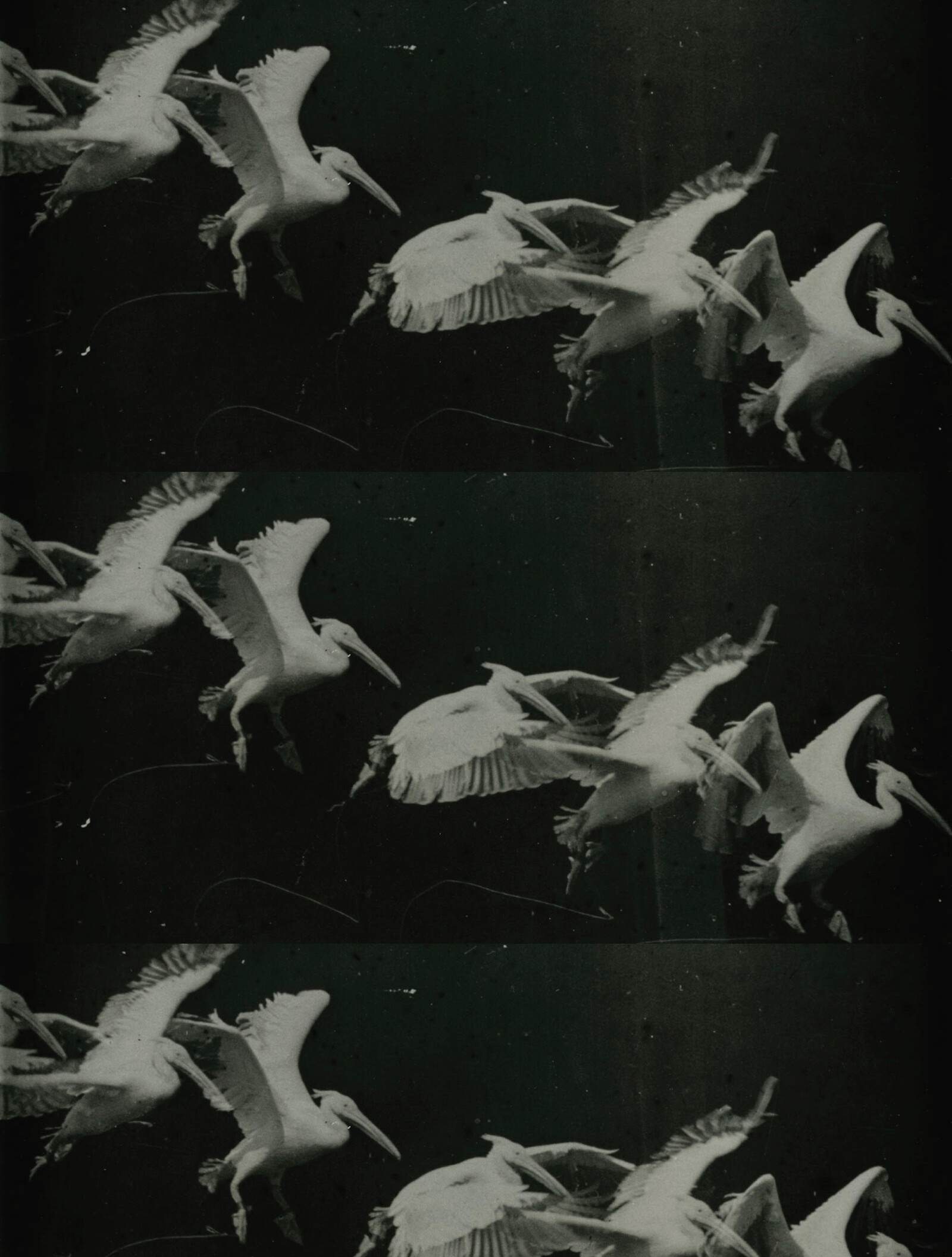

The animal who is your kin is called your warpiri. In the context of ngurlu, Daly Pulkara explained the meaning this way: warpiri is your “biggest sorry” (your greatest sorrow). In my words, warpiri is YOUR GRIEF. Your flesh and blood, flowing through the bodies of others who will be hunted, is your grief. You don’t have to grieve over everything; you couldn’t. But here, in this place of encounter with the necessary deaths of others, your grief may become extreme and so may your anger. If these deaths come about in defiance of Law, righteous anger is directed to those who have not managed death properly.

With the cybernetization of the world, both the human and the divine are downloaded into a multitude of tech objects, interactive screens, and physical machines. These objects have become genuine crucibles in which visions and beliefs, the contemporary metamorphoses of faith, are forged. From this standpoint, contemporary technological religions are expressions of animism.

The mediated, sentient, and intelligent plant potentially invites us to think about nature, plants, technology, and ourselves-as-humans in different ways. As plants in particular are revealed as agentic, intentional beings, the mediated plant potentially invites us to develop more caring, attentive, and communicative attitudes toward the vegetal. In this way, the mediated plant can push us forward in the urgent “struggle to think differently” that Val Plumwood called us to join. Perhaps the mediated, sentient, intelligent plant can help us to queer nature, to queer botanics, to queer ourselves-as-humans as we “go onwards in a different mode of humanity.” But why to queer? Why not “simply” to “decolonize”?

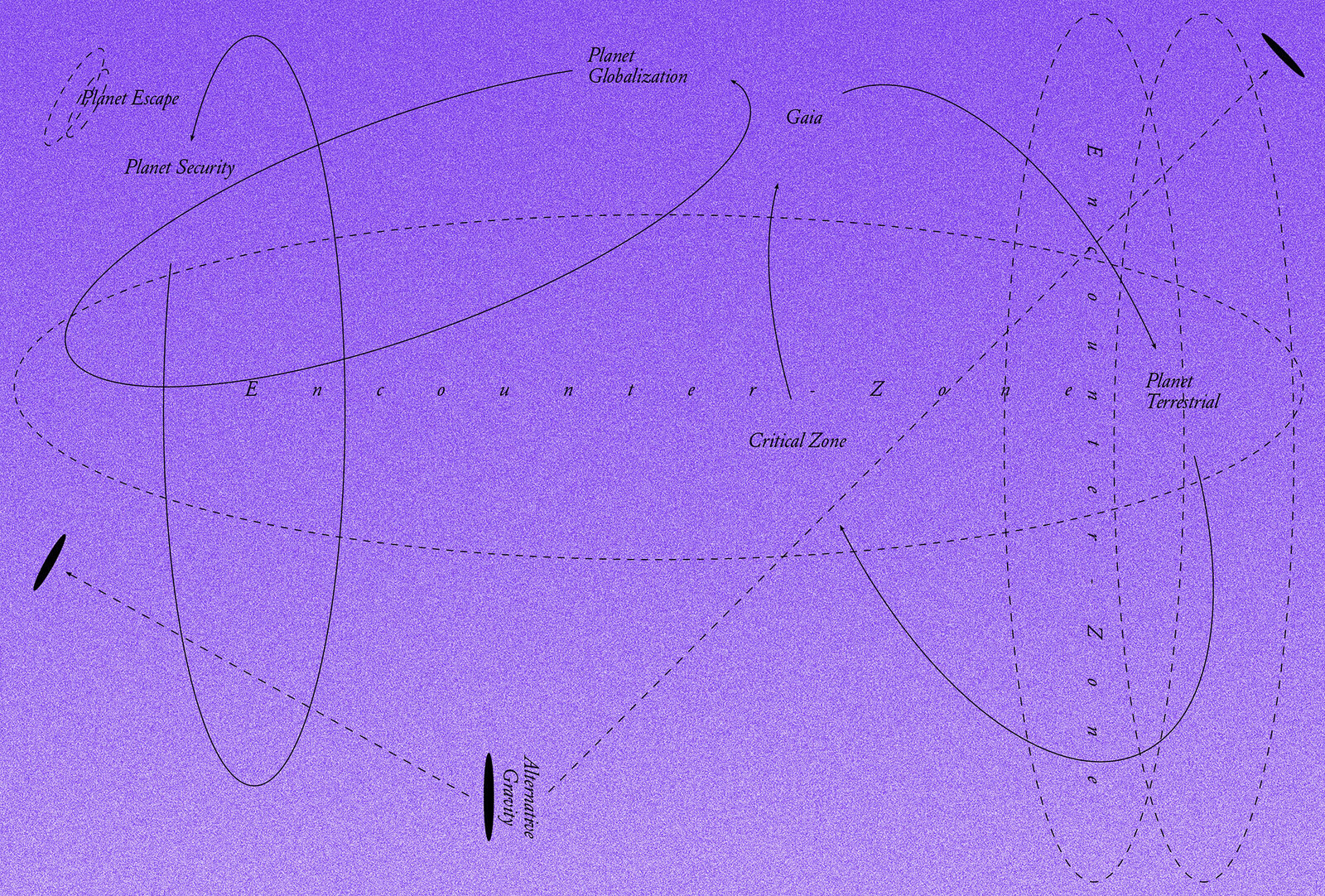

The Desert does not refer in any literal way to the ecosystem that, for lack of water, is hostile to life. The Desert is the affect that motivates the search for other instances of life in the universe and technologies for seeding planets with life; it colors the contemporary imaginary of North African oil fields; and it drives the fear that all places will soon be nothing more than the setting within a Mad Max movie. The Desert is also glimpsed in both the geological category of the fossil insofar as we consider fossils to have once been charged with life, to have lost that life, but as a form of fuel can provide the conditions for a specific form of life—contemporary, hypermodern, informationalized capital—and a new form of mass death and utter extinction; and in the calls for a capital or technological fix to anthropogenic climate change.