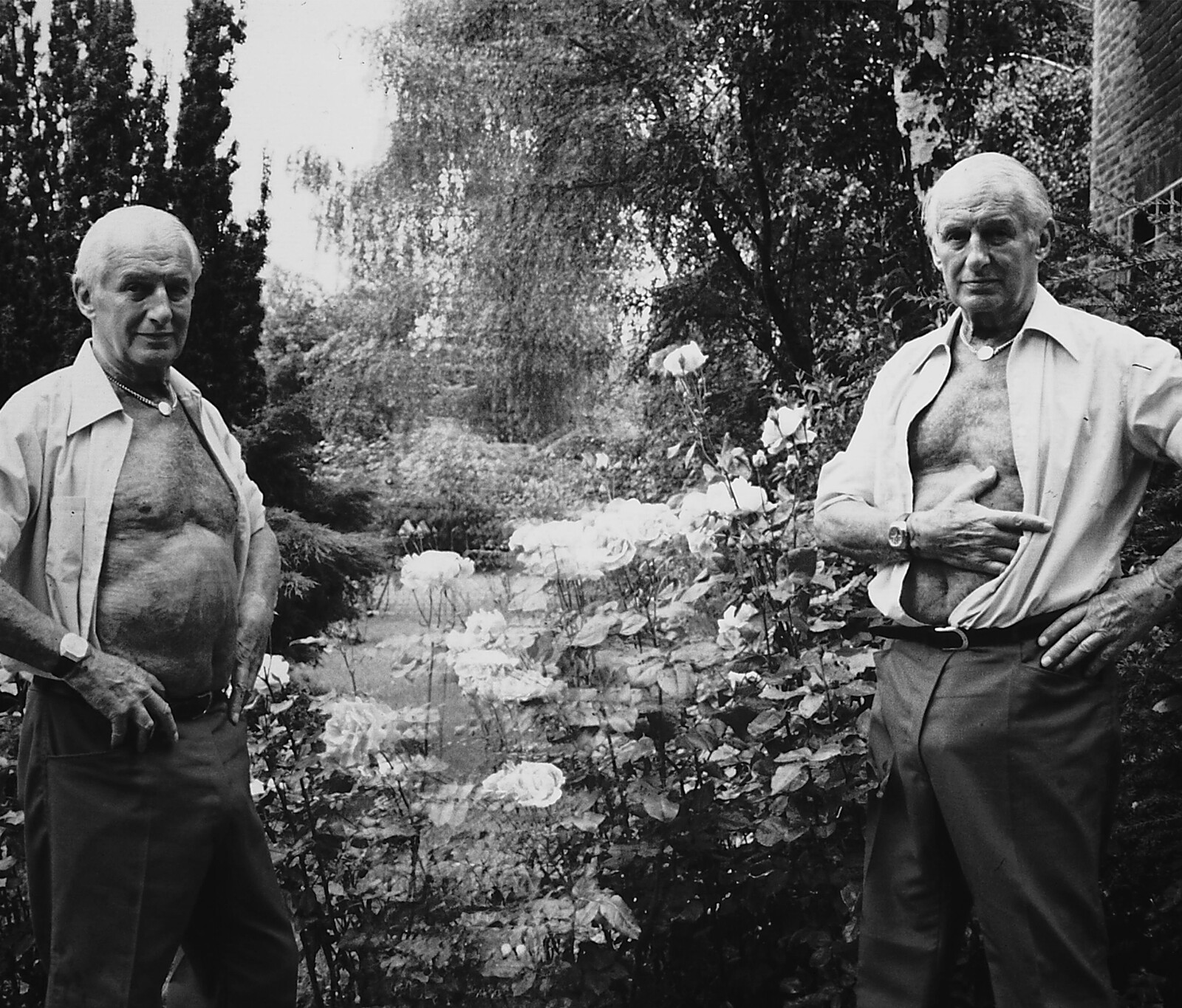

Adam Khalil

Inaate/se may not be the most obvious example of the science-fictional aesthetics of “Indigenous Futurism,” a term coined by Anashinaabe scholar Grace L. Dillon to describe Native artists who work with science fiction to both refuse the representational expectations of “the Great Aboriginal Story” and play with boundary crossings, claiming the spaces of science, technology, and futurity as their own. Nonetheless, the film employs certain key strategies Dillon finds in such authors, from what she terms “Contact” and “Native Apocalypse” to “Biskaabiiyiang,” an Anishinaabe word “connoting the process of ‘returning to ourselves.’” In so doing, Inaate/se promises an ethics founded on an inhabited futurity, which, no matter how many blows it has suffered, still manages to survive. The Khalils do not attempt to surpass the trauma of erasure; they inhabit and politicize it for a new world to come. In this way, they make the dystopia lived through seven generations a starting point for livelihood.

I’ll put it differently this time: the sovereignty of survivors.

Screening of INAATE/SE/ by Adam and Zack Khalil