We’ll let you guys prophesy

We gon’ see the future first

—Frank Ocean, “Nikes”

1.0

The first shot of Chef’s Table finds chef Grant Achatz standing before an abstract painting. “We would go to art galleries,” he says in voice-over, “and you would see these giant-scale pieces of art, and I would always say, ‘Why can’t we plate on that?’” Cut to a top-down shot of a dinner table. A rubbery cloth unrolls, left to right. Violins chime and arms clad in chef’s whites dip spoons into little ceramic pots of sauce, brown and white and yellow, trailing skeins across the tabletop.1 A version of this Pollock-like “splatter plating” serves as the opening title for the second and third seasons of Chef’s Table, as if to telegraph through this widely legible gesture a notion of creative genius: food can be art, too, and chefs artists.

Jack the Dripper of haute cuisine? Yes, and no. A star in the world of molecular gastronomy, Achatz is a particularly granular sort of chef. His restaurant Alinea features chemically inflected dishes engineered to produce beguiling effects. In his kitchen—which, the critics note, looks like a lab—Achatz and his crew realize such visions as floating candy balloons, white beans served on pillows of nutmeg-scented air, and mini piles of edible rubble made of mushrooms and herbs and spritzed, graffiti-style, with carrot juice.

Nods to fine-art and street-art formalism aren’t what make Achatz’s dishes art; rather, it’s the touches of genius that the auteur chef gives to edible matter that allow him to invoke a mélange of artistic lineages. Art here is an abstract added value—an unnamable quality of being-art, not immediately accounted for by the chemistry of the dishes and so requiring some supplementary and unsubtle signification. Achatz’s work is an extreme case of the dynamic characterizing most haute cuisine wherein the artistry and experience of the meal wildly exceed its nutritional value. Even the most perfect tomato won’t sell for $400, points out Abigail Fuller, one Chef’s Table director. But purée that same tomato, press and freeze it in the shape of a strawberry, and you can charge whatever you want.2

Of course, such a tastefully constituted strawberry still “tastes” (is flavored) like tomato. Achatz and his peers animate the opposition between flavor and taste that organizes so much aesthetic debate. Flavor is the brute recipe, the chemicals that so prosaically trigger our tongues and noses in order to produce the more ephemeral, rarefied quality called taste. What is tasteful is often derided as flavorless, minimal, and austere, while excessive or obvious flavoring (neon-orange cheese, “blue”- and “purple”-flavored drinks) is a sure sign of tastelessness, commonness, and vulgarity. Burping, farting, or eating Fritos in public are tasteless because they represent a capitulation to the body and its collection of instincts, and a corresponding betrayal of the social. Displays of taste, by contrast, reinforce the social against the bodily instincts that would deny its presence. Alongside Greenberg’s heroic Pollock is Pollock the cook, Pollock the dancer, and Pollock the alcoholic.

Still from Netflix’s Chef’s Table (Season 2, Episode 1), with American chef and restaurateur Grant Achatz.

If the body, and by extension, eating is a problem, haute cuisine proposes to solve this problem by refashioning the rote task of nutrition as a pleasurable, aesthetic experience. The instinctual, antisocial body is a source of unfreedom from which the steady cultivation of taste promises a flavorless escape. The vulgar necessity of food is not so much denied as transformed, patronized, and adorned to the extent that flavor is once again woven up inextricably with taste.

This is not the only solution. In 2014, Rosa Foods released the first commercial version of the nourishing beige powder called Soylent. The solution it offers is the opposite of haute cuisine: instead of maximizing the aesthetic potential in food, it minimizes how much thought we devote to eating. Soylent, says the copy next to its panel of nutritional information, is a product that is “not intended to replace every meal” but that “can replace any meal.” For roughly $3 per four hundred calories, Soylent succinctly fulfills the nutritional role of food, leaving you free to enjoy only meaningful cuisine. In other words, only tasteful meals need be concerned with flavor; for everything else, there’s Soylent.

The triumph of taste is written into Soylent’s founding myth. Tired of subsisting on ramen noodles and kale while his killer app floundered at famed start-up incubator Y Combinator, Rob Rhinehart applied an engineer’s approach to the problem of nutrition. The sci-fi dream of complete, compact meals was rediscovered, not in pill form, exactly, but as a blend of pulverized nutrients. Mix with water, drink, repeat. After four weeks of consuming nothing but Soylent, Rhinehart reported that his “quantitative” health had improved across the board, from body mass index to cholesterol to lipid counts. The qualitative results were more dramatic:

My mental performance is higher. My inbox and to-do list quickly emptied. I “get” new concepts in my reading faster than before and can read my textbooks twice as long without mental fatigue. I read a book on Number Theory in one sitting, a Differential Geometry book in a weekend, filling up a notebook in the process. Mathematical notation that used to look obtuse is now beautiful. My working memory is noticeably better. I can grasp larger software projects and longer and more complex scientific papers more effectively. My awareness is higher. I find music more enjoyable. I notice beauty and art around me that I never did before. The people around me seem sluggish. There are fewer “ums” and pauses in my spoken sentences. My reflexes are improved. I walk faster, feel lighter on my feet, spend less time analyzing and performing basic tasks and rely on my phone less for navigation. I sleep better, wake up more refreshed and alert and never feel drowsy during the day. I still drink coffee occasionally, but I no longer need it, which is nice.3

Alongside boasts of increased focus and productivity, Rhinehart’s self-assessment emphasizes an appreciation for the beauty of math equations and a heightened sense of the art of the everyday. Peeling back and optimizing low-level tasks, like nuking quesadillas, allows for higher-order cognition—math, music, art; culture. Against the dystopian vision of a foodless life, where workers gulp down four hundred calories without leaving their cubicles, Soylent presents itself as a product that lets you prioritize what you enjoy—including food. Official product shots for the first premixed Soylent, called Drink, feature people jogging, hiking, and listening to music. In one, a woman squeezes paint onto a palette on her desk, near small canvases dotted with abstract forms like heavenly bodies in a void. Among her paints and brushes is a bottle of Soylent. During the 2017 Major League Hackathon tour, Soylent encouraged coders to decorate their Soylent bottles and post their art with the hashtag #soylentcanvas.

Cliché or not, Soylent’s invocation of art and creativity manages to repackage the pairing of total abstraction and high taste for the new millennium. (The questions, corpse-like, return: Is abstraction tasteful? Does it have a flavor? Does it take us out of our bodies or deeper inside them?) The Coffiest Cafe, an immersive brand experience promoting a new caffeinated variant of Soylent, occupied a Los Angeles Arts District storefront for a few days in 2016. Styled like a smokeless tech incubator, the Coffiest Cafe nevertheless aspired to the clubhouses where the last century’s creatives gathered for face time—Parisian cafés and SoHo lofts. Anchoring the decor was RockGrowth 350 by Arik Levy, a big chrome piece of neo-modernist plop art, like several silver Judds tossed into a starburst.4 To one side, a bank of commercial refrigerators rose behind a bar resembling the black-over-white Coffiest bottle extruded into a sculpture by Anne Truitt. To the other stood a few chairs and round tables, the café furniture of a bygone era. An unfinished brick wall was dutifully decorated with—not coffee shop art, exactly, but Coffiest art: the two-tone bottle pictured among roasted beans and designer mugs.

Beyond invoking the aura of abstract art, the company has also employed actual artists. The design/marketing firm OkFocus, cofounded by artist Ryder Ripps, developed the original visual identity for Soylent.5 In addition to Abigail Fuller, panelists at Coffiest Cafe included Kibum Kim, a dealer/gallerist and an instructor at Sotheby’s Institute; Samantha Culp and Andrea Hill of Paloma Powers, an art- and artist-driven marketing agency; and Sean Raspet, a contemporary artist specializing in scent- and flavor-based artworks. At the time of the Coffiest Cafe in September 2016, Raspet was in fact employed by Soylent’s parent brand Rosa Foods as a flavorist.

Like Achatz, Raspet appeals to smell and taste—the so-called chemical senses—as much as to sight. For the work (-) (2012–15), Raspet reverse engineered the formula for Coca-Cola, then reconstituted it with enantiomeric versions of the molecules—a kind of chemical bootlegging, in which asymmetrical molecules are mirrored, like backwards Nike swooshes. Another piece, Phantom Ringtone (2013), is a “Fragrance formulation and propylene glycol in HDPE container on steel wall mount; 4.5 Litre bottle” that tastes like the sensation of thinking your phone is buzzing when it isn’t. Other works from the same period, like Ester Vector (2014), consist of molecules selected for their structure, not their scent—recalling systems-based conceptualism as much as all-over abstraction. Raspet notes that the language for tastes and scents is far less developed than that for sight or sound.6 This indicates the way perfumes and flavorings tend to mimic nature, or are derived directly from plants and animals. This also indicates the wide-open territory of chemical-based abstract art.

Raspet’s experiments led him to Soylent. In 2015 he became an employee of Rosa Foods, working both from their offices and from his own studio. His booth at Frieze New York in 2016 created a stir: instead of art, glass-doored fridges full of Soylent 2.0 lined the walls. In promo shots, models in futuristic gray Soylent jumpsuits posed with bottles and boxes.7 “My motivations for working with them had to do with having the formulations that I was making circulate in a larger quantity and in a larger cross-section of society,” says Raspet. “Also, [I was interested in] making an artwork that is a commercial product and is involved with the processes of production, rather than making art that was simply ‘commenting on’ these kinds of things without participating in them.”8 For Soylent it was a PR coup, and an introduction to a new subset of time-starved “creatives.” For Raspet it was a declaration that he was willing to work within the corporate sector, with tech start-ups, and even for them—to envelop his brand in theirs. Raspet’s prototype Pentagon 2.4 flavor debuted at Frieze, in the form of an algal paste; his Nectar variant was available to taste-test at the Coffiest pop-up, and in 2017 became his first commercially available flavor.

Raspet’s first Soylent artworks, Technical Food and Technical Milk (both 2015), comprise Soylent augmented with flavorful compounds characteristic of “food” and “milk”; an edition in powdered form is packaged in signed, numbered canisters.9 The project appeared as part of the Swiss Institute’s exhibition “Pavillon de l’Esprit Nouveau: A 21st-Century Show Home,” a chroma-key green living space furnished with 3-D-printed plastics, meant to “update” Corbusier’s infamous 1925 test home.10 Two dispensers near the entrance supplied Raspet’s milk- and food-flavored Soylents. There was no kitchen. In the opulent age of Art Deco, Corbusier’s factory-inspired interior was dismissed—like Soylent today—as alien, joyless, and dystopian; maybe so, but it was also the future.

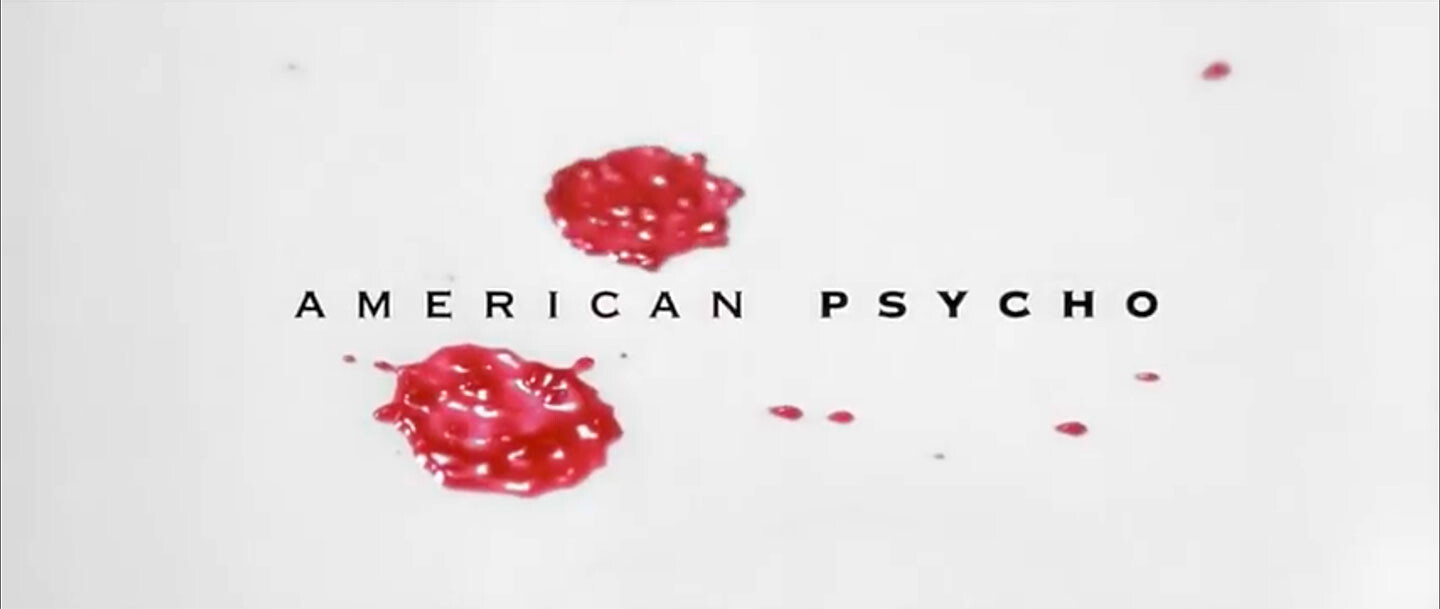

Film still from the openning sequence of American Psycho (2000), directed by Mary Harron.

2.0

A rich assembly of life’s most essential nutrients, the understated shade of PANTONE 14-1120, Apricot Illusion reflects the very essence of Soylent™. Open and transparent in its packaging and premise, dense and creamy in its appearance and taste, PANTONE 14-1120, Apricot Illusion and Soylent™ are inevitably connected to the classic tastes of simple and healthy eating. Soft and smooth, its inherent warmth and subtle complexity has a layered and expansive, yet thoroughly neutral presence. A color that is as old as time itself, and still completely modern in outlook and perspective, PANTONE 14-1120, Apricot Illusion speaks eloquently of Soylent™ and our continuing desire for foods that are both efficient and nourishing. If we are the continual servants of our own precarious metabolic pathways, PANTONE 14-1120, Apricot Illusion is our risk and our reward.11

What is the middle gray of taste? Rosa Foods describes Soylent’s flavor as “deliciously neutral.” Blog posts announcing updates to the formula note efforts to “provide the most neutral flavor profile possible.”12 Early versions even used, like Raspet’s Milk and Food, trace flavorings to enhance its “nonspecific” taste.13 “We were happy to discover,” wrote Rosa Foods, “that various Soylent 1.4 formula changes resulted in a flavor profile that met our neutrality standards without any artificial flavors. We have removed artificial flavors from the Soylent 1.4 formula entirely.”14

Like Raspet’s concept of an abstract chemical art, Soylent pairs a rigorous technological specificity with the opacity of a black box. “I think one of the areas where material becomes both exceedingly abstract and exceedingly concrete and specific,” says Raspet, “is at the level of molecules and purified chemical compounds.”15 A company that serves “food” in the most generalized, neutralized sense possible also touts the precision of its formula. The ingredients are listed on the various packages and enumerated on the website—along with their sources, from soybeans and sunflowers to algae and beets. Almost comically, Soylent boasts a “20% daily value” of two dozen micronutrients.16 Indeed, before launching Rosa Foods (as Rosa Labs), Rhinehart developed Soylent as “open source” via online forums, like the software many of its early adopters code for a living.17 Its products are numbered like release versions: Soylent Drink is 2.0, and Powder is currently 1.8. As with a good piece of software, Soylent’s back-end tweaking underlies a product meant to be frictionless—meant, in other words, to just work. Soylent users needn’t worry about how. In fact Soylent, in its efficient neutrality, aims for a kind of ubiquity and autonomy—an abstraction, a total formalism of food—that would transcend its physical substrate, even to the point of denial. Soylent’s slogan: Free Your Body.

In their minutely calibrated abstraction, both Raspet’s chemical works and Rhinehart’s Soylent resurrect a conversation familiar to abstraction and abstract art of the middle of the twentieth century—the bend in art history where abstract expressionism turned to color field and minimalism, then out into conceptualism and postmodern plurality. This narrative links Grant Achatz’s tablecloth to Pollock’s drop cloth to Raspet’s fridgefuls of Drink. As Raspet and Soylent explore the territory left open by the dearth of chemical-sense terminology and theory, they pick up where Clement Greenberg and his acolytes left off.

Where Greenberg’s formalism tried to resolve the paradox of materiality and abstraction through devices such as “opticality,” Raspet and Soylent maintain this paradox in suspension. This to the point of claiming a degree of neutrality for, or autonomy from, the “support”—in this case not canvases and stretcher bars but bottles and tanks, the ready-made containers of industrial chemistry. It’s remarkable how little Raspet and his critics discuss his work’s most visually obvious elements, the canisters of gas and grids of plastic jugs that contain his ephemeral compounds. Soylent obviously pays attention to its packaging, but it downplays it in a way few brands do. Its black-and-white minimalism signals a clean, utilitarian neutrality that would disappear if it could, the way a canvas would disappear. “At the time, the best option was to use existing, off-the-shelf stock bottles,” writes John Zelek on the Soylent blog. “After all, the innovation was inside the bottle, and the bottle was just a bottle.”18

As Greenberg puts it in his essay “Modern Art,” the modernist sensibility doesn’t critique from without, but from within—from an immanent position, the way Kant undertook a logical critique of logic.19 Rather than remain an objective observer, the modernist participates. Thus Raspet’s entries into the art world and his work for Soylent/Rosa Foods are largely coextensive. Indeed, Raspet is more deeply imbricated than his peers who are investigating a similar slice of the Venn diagram between an artist’s brand and a corporate one. The 9th Berlin Biennial in 2016, for example, for which Raspet produced a limited edition package of the Pentagon 2.4-flavored, algae-based, Soylent prototype (Soylent Paste 0.10),20 also featured projects from Deborah Delmar Corp. (an “actual” green-juice bar and coffee shop), and Christopher Kulendran Thomas (the New Eelam housing subscription app, which applies neoliberal entrepreneurship to the egalitarian utopia that Sri Lankan Marxists failed to gain by force).21 The biennial was curated by the four members of DIS, ambiguously positioned between a magazine, an art collective, a marketing firm, a fashion label—and, as of this writing, newly relaunched as an online edutainment channel. At the heart of such ventures is the question of corporate structure—corporate from corpus, meaning body. If corporations seem tasteless to us, perhaps this is because they do not sufficiently camouflage their embodiedness, but instead publicly, materialistically flaunt their corpses.

Raspet left Soylent in September 2016. His latest venture is a company called Nonfood that will sell algae-based nutrient bars.22 In late 2017, the group participated in the Food-X food-tech accelerator, and also shipped their first prototype. In this respect, Raspet can credibly claim to be independent of the art system—an artist-driven brand, without being art. The difference may simply be that Raspet has a company, a corporate structure, a body, while others only have galleries.

Does the artist change the corporation—or does the corporation change the artist? K-HOLE, a collective of artists, designers, and other creatives, got their start releasing free trend reports as PDFs. As founding member Dena Yago writes, “The project grew out of a frustration with an attitude common among Gen X artists, who liked to neg on younger artists for not keeping their distance from the inner workings of capitalism—for ‘selling out’ … With K-HOLE,” she continues, “we were not interested in taking on the role of ethnographer or performer; we were interested in the total collapse that comes with being the thing itself.”23 The reason for this was the renewed awareness of bodily needs experienced in precarity. Yago writes, of those who accused K-HOLE and their cohort of shilling, “They acted as if our decision to engage was motivated by anything other than awareness of the immediacy of recuperation, survivalism, and the deep-rooted anxiety brought on by the recession and student debt.” Their interests led to possibilities of corporate engagement as contractors to real companies. Sean Monahan, another K-HOLE alumnus, later created an actual advertisement for Casper Mattresses, a web-based disruptor in their field. The subject of the website Monahan produced was not bedding, but its abstraction: sleep itself.

Alas, Casper sells mattresses. Even Nike, say—Naomi Klein’s exemplar of abstracted, brand-based value—still sells shoes. The physical product haunts these brands; as much as they might outsource their production, becoming image-managers rather than manufacturers, the substrate returns abjectly in container-ship wrecks and sweatshop fires. Likewise, tech entrepreneurs do all they can to conceal any physical infrastructure behind the product’s front-end interface. And the more insubstantial the back-end, the better—the more fully imbricated they can become—tending toward the ultimate goal of brand without substance—the pure product. Here again, Soylent is more like a tech company than a food company, in that its fixation on the body, such as it is, predicates the forgetting (“freeing”) of the body. “I’d rather focus on entities that can be consumed and provide a metabolic function,” says Raspet, “rather than a kind of artwork that is a static object and needs to be stored.”24

This non-object status, or preference for transcendent effects over the necessary substrate, is crucial to the projects under discussion here—Achatz, Soylent, and Raspet alike. It’s crucial, moreover, for them to locate their artistry not in the base matter they manipulate, but in the temporary effects it produces. Yet the process of eating, too, remains woefully physical—even where food has been abstracted. Sarat Maharaj aligns the notion of artistic research—of the Achatz or Raspet kind—with “digestion,” through a particular wordplay of Joyce, by which he etymologically collapses the lowly tongue along with the more refined eye and ear into a sort of sensate wad:

By knowledge production I do not mean something conceived—Cartesian fashion—as “strictly” mental but as spasms and episodes of the mind-body continuum. Joyce’s “false-meaning” etymological chain dramatizes the point:

Gyana

Gnosis—gnoseology

Knowledge

Visible-audible-noseable-edible.The Sanskrit word “Gyana” or “Knowledge” retains the link with the physical through “gyana-yoga” practices. With “Gnosis,” knowledge is inflected as a more hived-off, mental affair—something Joyce trips up with his pun on “nose”: “knowing” takes place through the smell-organ and olfactory sensation, “lowest” of the faculties. “Knowing via the nose” cuts across Cartesian mind/body divisions and dualisms. With brain muscle-mind circuits, Joyce telescopes eye-ear-mouth in a single digestive conveyer belt.25

Add this to Joyce’s famous passages detailing the sense of a frying kidney and, at the other end, a trip to the outhouse. Maharaj argues that Joyce offers information to all of the senses in a way that “cuts across” the mind/body dualism. Artistic research is located not in digestion itself but in an overlying wordplay; language turned against language. Such research is immanent in the artist, physically and abstractly, the way food is immanent within the body—and the way an artist like Raspet is immanent within a corporation like Soylent. Or the way art is immanent not in the can of shit but in the artist’s (say, Manzoni) signing such a can.

This immanent critique occurs less in the physical product than in its overarching abstract form—the brand itself. Branding is the medium at stake, approached with a certain good faith historically reserved for abstract painting. To the notion of a detached “opticality,” we can add the brand—as pure a product as one can imagine: a dream of content without substance, abstraction without concreteness, image without substrate, idea without object … mind without body. This pure brand is the insubstantial magic that the artist brings to brute matter—from the pureed tomatoes at Alinea, to the mass-produced chemical variants that travel by boat from China to Raspet’s studio, to the powders and extracts ingeniously combined in each bottle of Soylent ready-to-drink food. The artist (researcher, engineer, entrepreneur) imbricates a brand with hidden value. As Barthes might have phrased it, the artist flavors the world.

The trajectory of material to immaterial restates the directionality of the historical avant-garde’s increasing abstraction, increasing autonomy, and increasing denial. Like the Greenbergian modernist, the artist-entrepreneur does not critique the system in order to destroy it but uses the characteristics of their medium to shore up its preeminence, to progress, to take their chosen form into the future. Faith in technology or tech-driven brands replaces faith in art. In lieu of an avant-garde in the classic modernist sense, we now have an avant-garde in the mold of Silicon Valley. Apple, Uber, Soylent—artists in this avant-garde emulate the start-up model, they participate in it, they willfully use it and are willfully used by it. Entrepreneurs, not artists, will see the future, but artist-entrepreneurs can come along.

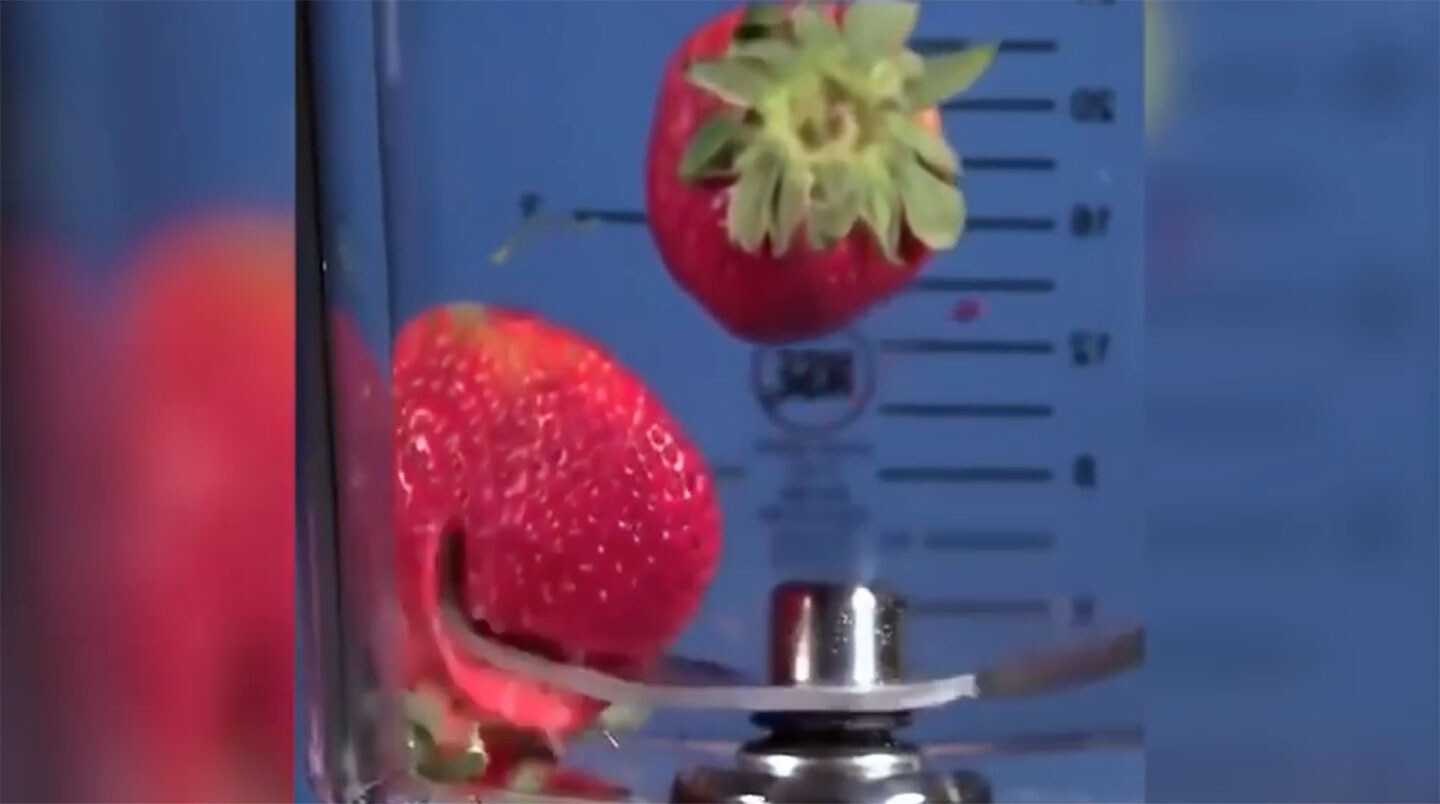

Film still from the promotional video Soylent 2.0: Now Shipping by Burning Film Productions.

The potential for real social change in something as socially imbricated as food is as exciting as any space program. At least one writer has noted that Raspet’s interest in a modernist sense of progress is perhaps closer to that of the Bauhaus and the “designed life” than to the cloistered discourse of Greenbergian high modernism.26 And yet this interpretation smudges the elisions of applied modernism’s faith in abstraction, in purity, and in ubiquity. As Eunsong Kim and Maya Mackrandilal write of the self-styled neutral subject, “He insists on the freedom to be abstract—the freedom to be clean and naïve.”27 The one-food-for-all approach, when it does look back, looks at the mess of cultures and cuisines and sees edible rubble, graffitied with carrot puree. Soylent imagines a future without history.

Science fiction has given us memorable figurations of capitalism as an unchecked, motile cancer. Mark Fisher points to John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982); Steven Shaviro ends his primer on accelerationism with a vision of post-human parasites learning to survive in the “monstrous” body of capital.28 Rather than actively malignant enemies, such corpses are better defined as metabolisms with an alien, inscrutable, even passionless logic. These metabolisms, like our own peristalsis—the coordinated contractions of the esophagus, stomach, and intestinal walls—propel material in one direction only: “futureward.” Such an unsightly motor works best when masked by a tasteful abstraction. Taste folds into flavor; the abstract appears concrete. The brand collapses into the corporation, their difference harder and harder to discern. The avant-garde contracts, becomes de rigueur; successive normalizations of the avant-garde propel the bolus and chyme and feces of culture … This is the action Soylent accomplishes by its twin appeals to specific chemistry and abstract nutrition. Soylent outpaces its dystopian reputation, as if it were never “people.”

“Flavor,” the raw stuff; “taste,” the art. Jackson Pollock was a foodie, but not a gourmand. According to one collection of his and Lee Krasner’s recipes, the painter favored traditional American dishes like meat loaf and apple pie.29 The avant-guardist who famously pissed in the fireplace of the patron who, among an elite few, recognized Pollock’s genius in the raw material is now as prosaic as that story. In this metabolism, the artist, consumed by and consumer of the corporation, is not only digested, but provides the calories that fuel the digestive organs. The self-aware avant-guardist recognizes, and does not escape, their bacterial role.30

Still from a YouTube compilation of The Most Satisfying Video In The World.

Through such a “telescoped” mind-body continuum, the Soylent brand renders its “corpus” as natural as an ideology. Proceeding from the middle gray of taste, the “user” becomes if not an artist, then a “creative”; the white bottle, like the white cube, promises an autonomy that can be re-specified to taste—resisted, added to, expressed on. Where food is involved, it collapses this separation between, as it were, the canvas and the art—telescopes the distance between the substrate and the sign. The result is a new neutral, a new self-evidence—the staple food of the future. Thus Rhinehart and Raspet make the case for the efficiency, even the sustainability, of their respective foods. An aesthetic purity distilled with no waste—what you need, no more and no less: Is this truly anticapitalist capitalism? These corporations seek a way out of (or through) postmodern constipation; and while this too is a process most tastefully concealed—and while Rhinehart hedges on this question in his blog posts—the result remains: yes, you still shit.

Soylent by Rosa Foods, Inc., a nutritionally complete ready-to-drink meal, is made largely from the main protein found in soybeans. Rosa Foods wants you to know exactly what your food is made of. They make no secret of the fact that they use GMO ingredients where possible, since the benefits in efficiency and environmentalism outweigh the risks of harmful mutation. In the Harry Harrison pulp novel Make Room, Make Room! (1966), the earth is overcrowded and the seas are dead; Soylent is a desperate ration made from soy and lentils. In the 1973 film adaptation, Soylent Green, even though the earth is overcrowded and the seas are dead, the Soylent Corporation claims its product is made from “plankton.” Rhinehart named his product after the former, not the latter, although he relishes this dystopian echo.31 Corporations aren’t people so much as bodies—bodies that metabolize without living. Corporations are people in the way that Soylent Green is people.

The title sequence for Mary Harron’s 2000 film American Psycho—a blood-like sauce drizzling onto white plates—neatly triangulates the abstract corporate appetites under discussion here. See →.

Abigail Fuller made comments to this effect while participating in a panel at the Coffiest Cafe in downtown Los Angeles, September 25, 2016.

Rob Rhinehart, “How I Stopped Eating Food,” Mostly Harmless, archived at →.

See Arik Levy’s website →.

OkFocus has also done website work for Nike and an online/Tumblr-based art auction for Phillips, among dozens of other branding projects. See Karen Archey, “Review: Ryder Ripps,” Frieze 170, April 2015 →.

The uniforms, designed for the occasion by Nhu Duong, resembled space suits as much as work wear.

Quoted in Joel Kuennen, “The Matter of Molecular Practice: An Interview with Sean Raspet,” Artslant, June 23, 2016.

Molecules meant to “represent” abstract ideas of food and milk, the bases of adult and infant life, were “provided at approximately 0.1% in Soylent™ vehicle.” See the Swiss Institute press release →.

See Lucy Chinen, “Corbusier’s Kitchen” →.

Copy by Laurie Pressman, vice president of Pantone, printed on the base of a limited edition of one hundred Technical Milk and Technical Food canisters.

“Soylent 1.5 Has Arrived,” Soylent Blog.

Rob Rhinehart interviewed by Steven Colbert, The Colbert Report, June 11, 2014 →.

“Soylent 1.4 Begins Shipping Today,” Soylent Blog.

“Sean Raspet in conversation with Ceci Moss,” Cura →.

See the macronutrient overview on the Soylent website →.

John Zelek, “How to Design a Bottle,” Soylent Blog.

“I identify Modernism with the intensification, almost the exacerbation, of this self-critical tendency that began with the philosopher Kant. Because he was the first to criticize the means itself of criticism, I conceive of Kant as the first real Modernist. The essence of Modernism lies, as I see it, in the use of characteristic methods of a discipline to criticize the discipline itself, not in order to subvert it but in order to entrench it more firmly in its area of competence. Kant used logic to establish the limits of logic, and while he withdrew much from its old jurisdiction, logic was left all the more secure in what there remained to it.” Clement Greenberg, “Modernist Painting,” 1960. Available at →.

See Sean Raspet’s artist page for the 9th Berlin Biennale →.

See →.

Cofounded with Lucy Chinen, Mariliis Holm, and Dennis Oliver Schroer. See →.

Dena Yago, “On Ketamine and Added Value,” e-flux journal 82 (May 2017) →.

“Sean Raspet in conversation with Ceci Moss,” Cura 24 →.

Sarat Maharaj, “Unfinishable Sketch of ‘An Unknown Object in 4D’: Scenes of Artistic Research,” L&B (Lier en Boog) Volume 18: Artistic Research, eds. Annette W. Balkema and Henk Slager (Rodopi, 2004), section 0014.

A. E. Benenson, “More of Less,” Art in America, February 2017 →.

Eunsong Kim and Maya Mackrandilal, “The Freedom to Oppress,” contemptorary, April 19, 2016 →.

Mark Fisher, “SF Capital,” Transmat: Resources in Transcendent Materialism (2001); Steven Shaviro, No Speed Limit: Three Essays on Accelerationism (University Of Minnesota Press, 2015).

See Julie Earle-Levine, “In the Kitchen with Jackson Pollock,” T Magazine, March 24, 2015 →.

And yet a 2018 web ad for Soylent reads: “Gyms have germs. Soylent has nutrients.”

See the Soylent FAQ →.