Digital simulations have an uncanny ability to proliferate, transform, and agitate. Ubiquitous screens and devices have defined the psychological formation of the younger generation. Immersive techniques and metadata management are transforming the techno-environment such that we should no longer think in terms of technology shaping self-perception, but instead of technology simulating the self, and then replacing the self with its simulation.

The technological downloading of human identity is the horizon of this evolution.

Cofounder of the AI startup Luka, Eugenia Kuyda designed a chatbot named Replika to speak with Roman Mazurenko, a friend who had passed away. A device intended for digital ghosts, Replika is only able to repeat questions and answers recorded in the past—a simulated reality where the identity of a person can be reactivated and queried.

“Become virtually immortal” is the purpose of Eternime, an online service that preserves people’s memories after their death. You can activate it while you’re alive by allowing the service access to your social media, and you upload photos and geolocation history. All data is stored and processed before it is sent to an AI avatar that virtually recreates your personality. The mission is to accurately reflect your personality as time goes by, thanks to your interactions with the avatar while you’re alive.

The Electronic Immortality Corporation, created by the Russian businessman Dmitry Itskov, is quite similar. It is part of the 2045 Initiative, which aims to transfer people’s individual personalities to avatars in order to achieve cybernetic immortality. According to Ray Kurzweil, by 2045 the cloud will back up our minds. We can call this effort to commit our lives to a digital archive “life-logging,” though “death-logging” would work just as well.

Life-logging and death-logging, as simulated experience, pose the theoretical problem of the limits of simulation: this problem is crucial in the current development of AI and the automation of living organisms. Basically, the issue is about experience. Can we simulate experience? Can we replicate it? This question obliges us to determine what “experience” means. The etymology of the term is useful: ex-perire has a Latin origin, which implies dying, as we see in the euphemistic use of “expiration” to mean death. Per-ire in Latin means “to go beyond,” “to die.” The word “experience,” then, refers to the process that leads living organisms to death. Time, decline, exhaustion, and finally extinction are indissolubly linked to the concept of experience.

This is why, from a philosophical point of view, artificial intelligence, while simulating human activity and replacing the living organism in many social domains, cannot access the dimension of existential experience. The individual consciousness of duration, of time, and therefore of extinction cannot be simulated nor replaced by any intelligent machine. Consciousness only exists in the dimension of time, and time is only perceivable against the background of being destined for death.

This has not stopped individuals from trying to make eternity accessible by storing and downloading data. An antecedent of the above-mentioned projects is the lifelong art experiment of the Finnish artist Erkki Kurenniemi, initiated forty years ago and entitled 2048. His challenge was to create a multimedia archive to store a retrievable memory of his existence. He believed that by July 10, 2048—his hundred-and-seventh birthday—a quantum computer would be able to digitally upload a human being, and he would thus be able to reactivate his own life for the post-Singularity world.1 The archive is intended to be activated for public use on July 10, 2048: people will be able to “play” it like a game or a multimedia show.

Born in 1941 in Hämeenlinna, Finland, Erkki Kurenniemi was a pioneer of multimedia art. A techno-utopian and enthusiastic scientist, he was passionate about his vision for the future, which was rooted in the cyber-utopian counterculture of the 1960s, and which extended to diverse fields like robotics, electronic music, experimental cinema, and interactive installations. He was active in the early development of analog computers and synthesizers, and in the creation of multisensory devices. Simon Reynolds, in his book Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to Its Own Past, describes him as “a hybrid of Karl-Heinz Stockhausen, Buckminster Fuller, and Steve Jobs.”

Already in 1970 Kurenniemi stated, “Our true descendants will be algorithms.” Like Ted Nelson and other pioneers such as Hans Moravec and Marvin Minsky, Kurenniemi explored the impact of new technologies on the evolution of human beings. Always a provocative advocate of the role of technology in our collective future, his wild interdisciplinarity presents a different story than the cybernetic-centered American one.

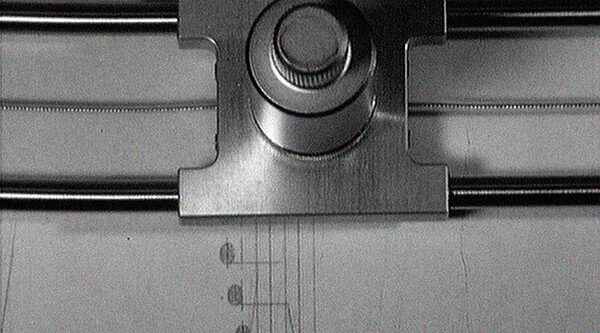

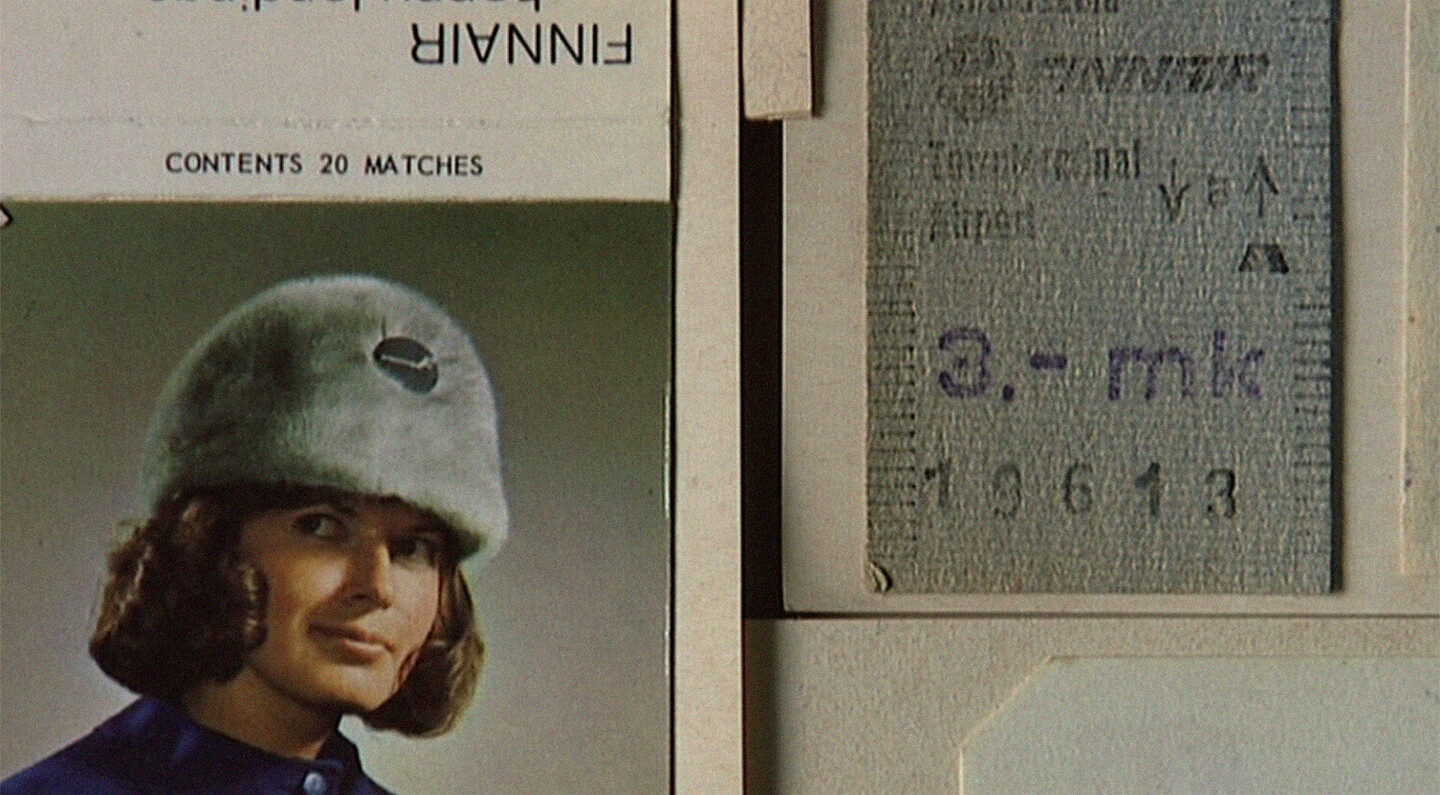

Following his belief that AI would outpace the biological brain, Kurenniemi spent more than forty years collecting hundreds of hours of audio cassettes, recording his encounters with friends and strangers in video diaries (in the 1960s he shot 8mm and 16mm home movies; subsequently, he used VHS, video, and mobile recording), collecting objects from his day-to-day life such as newspapers, magazines, receipts, movie tickets, notes, etc., and taking twenty thousand photos per year. He suffered a stroke in 2005, and on May 1, 2017 he died, after a long disability.

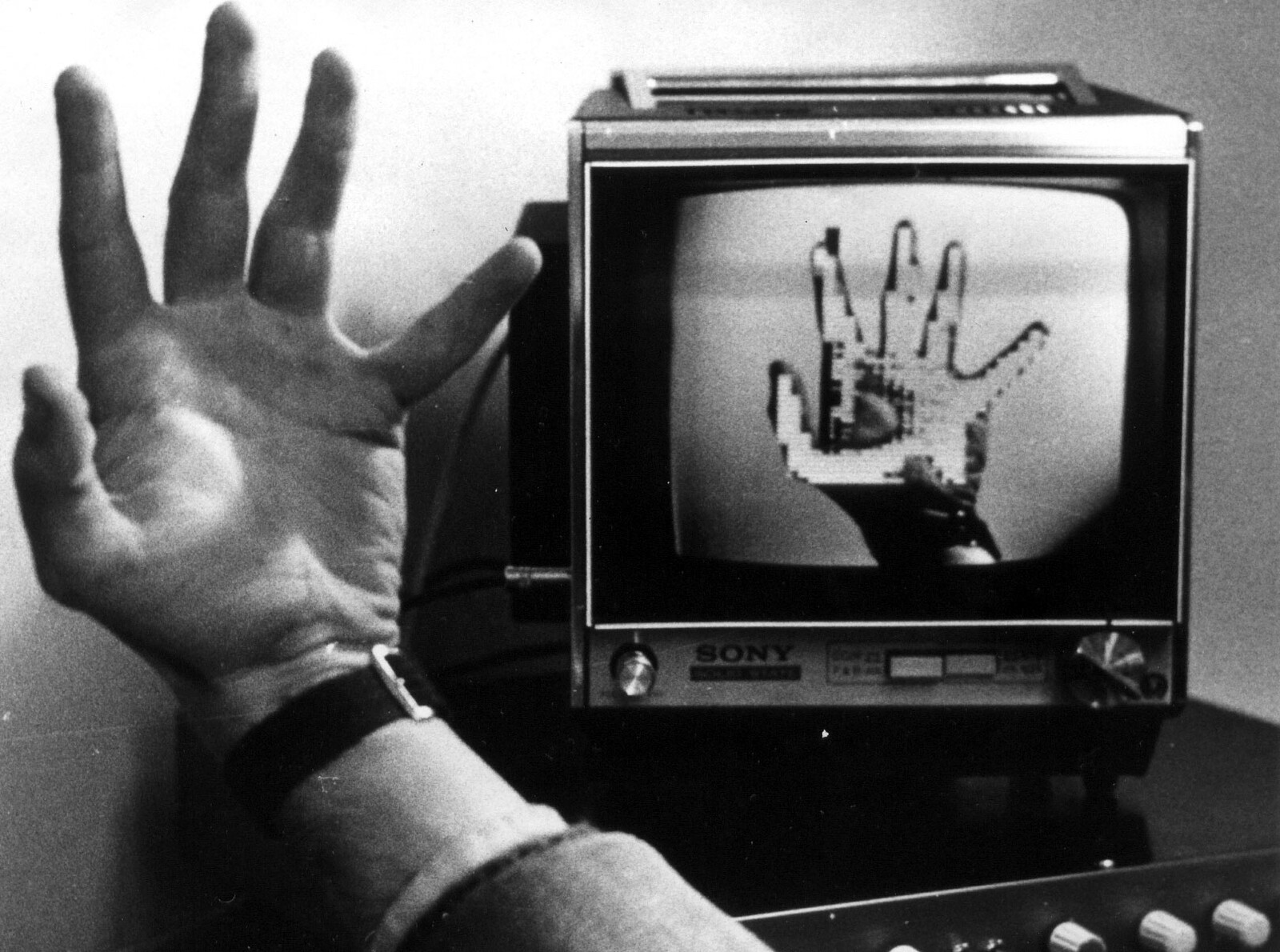

Kurenniemi was head of planning for Heureka, a science center in Vantaa, Finland. He built robots for Nokia and produced more than a dozen experimental films. Nevertheless, he considered himself a dropout, always in search of new challenges across disciplines. Interested in synesthesia, he developed various musical instruments and interactive tools for shared perception. Inspired and fascinated by bio-music—brain waves that are transformed into sound—he created the DIMI (Digital Interactive Musical Instrument) series. Dimi-O (aka Optical Organ, 1971) is based on a bio-feedback and optical interface that can be played by using a video camera or a keyboard. Dimi T (aka Electroencephalophone, 1973) uses the player’s electrical brain activity to control the signal of the device.

His inventions and his compositions influenced a generation of avant-garde electronic music composers around the world, even if he remained almost unknown outside the Nordic countries until his 2012 exhibition “In 2048” at Documenta 13 in Kassel.

Kurenniemi was looking for a new sensorium through technological instruments and fleshy excitements such as alcohol, drugs, sex, and combinations thereof. In his life, any boundary between science, music, physics, pornography, and technology was porous. Dimi-S (aka Sexophone or Love Machine, 1972) is a device that generates sounds through the skin contact of four performers who hold electrodes that generates bio-feedback. Each Sexophone session is unique, as the sound is generated by the electric conductivity of the players’ epidermises. The players are asked to follow some instructions to activate the machine, as in Fluxus or algorithmic art. Sexophone is an ironic forerunner of cybersex.

Sexual memories are present in Kurenniemi’s archive, recorded on different media—analog and digital videos, handwritten notes and digital files, audio recordings. Kurenniemi foresaw the exploding popularity of amateur pornography. His recordings are very different from the neatly groomed flesh of commercial smut. Kurenniemi and his partner performed in front of the camera, having sex, shaving their pubic hair, drinking, cross-dressing, and smoking joints. There is no editing of the images because what he wanted to record was life as it unfolded in time, through an approach that he called “Video Verité Totale.” Unrecorded sex was uninteresting for Kurenniemi, who said in his audio diary Chapter 2: A Letter Addressed to X that he “tried not to see people who were allergic to camcorders and video recording.”

Kurenniemi’s life-logging was the prehistory of contemporary networking. He focused on the symbiosis of man and machine before it became an everyday experience, like it is today in phenomena like social media. He paved the way for many contemporary projects that deal with self-surveillance, like MyLifeBits by Gordon Bell, who gathered images, recordings, lectures, texts, and voicemails between 1998 and 2007 and processed them through Microsoft archiving software. Lifestreams by David Gelernter and The Orwell Project by Hasan Elahi are other Kurenniemi-like projects—even if Elahi’s database is designed to block access to his life, with the overload of information crushing any attempts at surveillance.

Software Can Be Somewhat Immortal

Since 2006, Kurenniemi’s archive has been held at the Central Art Archives of the Finnish National Gallery. His archive contains videos, work-related documents, photographs, and personal belongings, among many other items. When conceived forty years ago, the archive was a futuristic project, but nowadays it is technologically outdated. For Documenta 13, Nicolas Malevé and Michael Murtaugh, members of the Constant group, developed a prototype online project based on Kurenniemi’s archive, which was also included in Kurenniemi’s 2013–14 solo show at the Kiasma Museum in Helsinki. What is significant about Kurenniemi’s project is its philosophical implications, not just its technical applications.

In Being and Time, Martin Heidegger remarks that “the essence of ‘being there’ lies in existence.” This means that the ontological foundation of the situational being—the living and conscious human organism—cannot be dissociated from the existential dimension, the dimension of ex-istere (being out of place). In order to explain the meaning of experience, Heidegger speaks of “being-towards-death” (Sein-zum-Tode). Computation lacks duration, because the abstract nature of digital constructs doesn’t belong to the sphere of death, doesn’t belong to the sphere of time, of duration.

In Mika Taanila’s film essay The Future Is Not What It Used To Be, made with footage and archive material from Kurenniemi’s life and work, Kurenniemi states, “We used to distinguish between body and soul. But in the computer age their meaning is obvious: there is hardware and software. We know that software can be somewhat immortal. Nothing kills good software except better algorithms.” The film explores the technological devices he designed and his theories about the future of the music industry and humankind. Back in the 1970s, he wrote that in the future, musicians would be programmers, thanks to the evolution of digital musical instruments. In less than one hundred years, he predicted, the earth would be turned into a museum and people would no longer age thanks to genetic science and nanotechnology.

In the film essay, Kurenniemi throws into question the technical possibility of simulated life and engineered intelligent behavior in a double way. As a scientist, he anticipates developments that would unfold in the following decades. As a composer and filmmaker—as an artist, that is (even though he considered himself a scientist rather than an artist)—he unveils a sort of melancholic sentiment around the loss that is implicit in his vision of a future in which human development is superseded by technology. Computation may perfectly replicate a body and a human brain, but this recombination is doomed to lack the existential meaning of experience. Similar scenarios were widely developed by the cyberpunk novelists of the 1980s and 1990s, with an air of unbearable distress and alienation.

In Creative Evolution, Henri Bergson wrote: “The universe endures. The more we study the nature of time, the more we shall comprehend that duration means invention, the creation of forms, the continual elaboration of the absolutely new.” A sense of duration is the essential feature of the self, which implies that existence cannot be reduced to a computational recombination. Duration cannot be computed, as duration is the suffering and the pleasure that the conscious sensitive organism experiences (ex-periendo—“by way of dying”). This complexity is present in Kurenniemi’s techno-visionary and ironically melancholic work.

See “Singularity Chat with Vernor Vinge and Ray Kurzweil,” kurzweilai.net, June 13, 2002 →.

Category

All film stills from the documentary The Future Is Not What It Used To Be (2002) by Mika Taanila.