For $11 an hour I stocked nonfiction and worked the register at Black Oak Books in Berkeley, a used bookstore otherwise staffed by aging, garrulous intellectuals without institutional affiliation. For $12 an hour I assisted Sam Green, a filmmaker whose first documentary, The Weather Underground, chronicled the radical group from the 1960s responsible for bombing the US Capitol, the Pentagon, and the United States Department of State. The Weathermen always phoned their targets beforehand, after the bomb had been planted, to avoid hurting anybody. I worked these jobs in 2007, before the economic meltdown and the sudden growth of the second tech bubble. It was a pre-Airbnb, pre-Uber, pre-I-can’t-get-a-reservation-anywhere-in-the-Mission-District-on-a-Monday-night San Francisco.

My partner and I moved from a divorcee’s guest room in Berkeley to fulfill a low-income requirement in an unfinished luxury loft of smoothly poured concrete near downtown. We lived there for four months until the unit sold for $1.2 million. We ended up at Artists Television Access, in a room occupied by Divine before the media arts organization with anarchist leanings moved into the building. I socialized with Marxist organizers from the labor union UNITE HERE!, Marxist graduate students from UC Berkeley’s rhetoric program, and Marxist workers from different affinity groups. Walking home from a book-group meeting with members of the Workers International League, I felt a surge of affect, like I was starting to accomplish what I had moved out to San Francisco to do—which was to be political.

After four months my knowledge began to feel unmarketable. I found myself wondering if I would ever be able to afford the objects that adorned my middle-class childhood memories. A job posting on the Bay Area Video Coalition website for a video producer led to an interview with an anonymous company in Mountain View. I was picked up by a middle manager named Bert in a Prius at the Caltrain station. As we drove past the Computer History Museum and into a large corporate campus, it occurred to me that I was competing for a position at Google, and had been, technically, since I’d stepped into the vehicle. Upon exiting, I confronted a chaos of identical, sky-blue cruiser bikes just organized enough to seem suspicious, like a set-piece for first-time visitors.

We entered 1600 Amphitheater Drive through one of many sets of large glass doors, and I halted in front of a row of six digital prints of the Google logo, all on the same 3 × 5 foot canvas, each one done in the style of a different modern master—Monet, Van Gogh, Matisse, Picasso, Dali, and Pollock. The Pollock was a basic Photoshop splatter-brush defacement, while the Monet was an epic travesty: an impressionistic GOOGLE floating nowhere above three lily pads. The Dali was a shotgun marriage between the Persistence of Memory and the famous insignia. The collapsed sense of space and time resonated most with its surroundings. “Yeah, they like to do art projects here,” said Bert impatiently.

After four interviews and a Final Cut Pro test session in which I edited reel of a company seminar with David “Avocado” Wolfe, the self-described rock star of the superfood and longevity universe, I was hired for a month-long trial period. If I survived I would remain a contracted employee, paid a salary of $34,000 by Mountain View–based Transvideo Studios to work full-time on the Google campus. I would enjoy perks like the endless swimming machine or a private Thai Massage in one of the only rooms in the Googleplex blessed with opaque walls. Too skeptical to make many friends and integrate, I frequently took my electric scooter around campus to systematically sample the offerings at each of the nineteen cafes, and to purify my anus with the arsenal of targeted functions on the Japanese toilets that graced each and every bathroom. I never missed an opportunity to reserve a conference bike for my team.

Shortly after I was hired, white and gray lounge chairs with spherical retractable hoods started to appear in open spaces without any corresponding memo or orientation. These were MetroNaps—sleep machines. On my third spotting I decided to get in, discovering remote controls on the arm that could adjust knee elevation, toggle between “sleep music” tracks, and set an alarm consisting of light and subtle chair vibrations. Unlike the Japanese toilets, MetroNaps weren’t branded with a national culture, authentic or otherwise; instead, they were always already international, produced for the jet-setting elite of the global information technology sector to “improve employee morale while boosting the bottom line.”

The first time I saw Sergey Brin he was gripping a ball not made for sport, but more likely for a child, or a dolphin, or at the very least an office, while talking to two other men in a clearing of personalized work stations. He was too short to have been a quarterback, in high school or anywhere else, but his chest was puffed out from beneath a long-sleeved performance base layer. He sporadically shifted his weight back and forth in royal blue Crocs, moving the toy between his hands, gesturing as he explained something to his less poised colleagues.

The first time I saw Larry Page he was eating alone with his head down in one of the campus’ peripheral cafes. I remember a moist yellow pile on his plate, which could have emerged from any number of cuisines—pan-Asian, Caribbean, Magyar—depending on the mash-up offered at that particular cafe. His blazer suggested he had just given a presentation to outsiders and he looked sort of sick.

One day Barack Obama came to campus and I spoke to him for three minutes. He coincides with an archetype of cool in a political system starved for hipness. I decided that this was the secret to his success. He lets you participate in the cool while subtly convincing you of your own bright future. “I love free pancakes,” I said, too quickly. “Me too, man,” he replied, patting me on the shoulder, “me too.” I didn’t get to talk to Al Gore when he visited for Google’s annual “Zeitgeist” conference, but I felt the wind as he stormed past me down a long hallway and into a bathroom like an animal anxious to shed its skin. I stood there holding my two signed copies of Bill Clinton’s book Giving, one of which I sold to Black Oak Books for $150. I’m still sitting on the other.

One day, after scrubbing the audio on the video of Anthony Bourdain giving a talk as an Author at Google and then exporting a Google Dance event performance by the employee troupe Decadance, I heard a woman screaming from the lobby. It was the type of screaming you might hear at a crowded Verizon store when somebody has just learned the cost of cancelling their contract. This wasn’t a common sound in the corporate offices of a company started by two Montessori/Stanford graduates, where employees take mindfulness-based emotional intelligence courses. A few of us crept towards the lobby to see a woman in a San Jose Sharks jersey confronting our building’s receptionist while clutching a printout of what appeared when she entered her name into Google. She had marched down to the headquarters to demand that the first two search results be removed. She was savvy enough to know the internet was produced and organized somewhere, but like most of us she didn’t fully understand how it worked.

The novelty of the environment evaporated, like a new operating system that doesn’t feel new for long. I would line-up off Market Street in San Francisco at 7:15 each morning, in order of arrival, with a group of coworkers—mostly men—wearing T-shirts emblazoned with logos for companies like DoubleClick and SurveyMonkey. We tried to keep an open mind regarding the queries, come-ons, and antagonisms of the also-mostly-male homeless community our lines snaked around. The luxury limo shuttle would arrive and take me to the office. There I would sit in front of two Apple Cinema Displays—sometimes editing and making graphics, sometimes mining information to leak to organizer friends. I read Antonio Negri and the luminaries of Italian Autonomist Marxism and anthropological studies of finance like Benjamin Lee and Edward LiPuma’s Financial Derivatives and the Globalization of Risk. Render time meant research time, and unlimited printing meant flyers for the events my friends and I would put on at Artists Television Access back in San Francisco. I began to suffer debilitating headaches around 3:00 p.m. and started doing stretches in my building’s empty gym during my afternoon break. After 9–12 hours on campus I would fill my Google-issued bag with Naked juices and to-go containers of food for my roommates, before getting back on the shuttle to ride Route 101 back to San Francisco. The nausea would set in when the shuttle pulled onto the freeway.

Something happened every day at 2:15 p.m. outside of the building next to mine. At first it registered as an unusual shape with unusual colors and an unidentifiable cause passing me consistently at the same time everyday. I came to realize that it was the same group of workers, mostly black and Latino, on a campus of mostly white and Asian employees, walking out of the exit like a factory bell had just gone off. Sequestered at the outer limits of campus, they would all get into their own cars: not Google shuttles like the rest of us. Hanging from their belts were yellow badges, a color I had not noticed before amongst the white badges of full-timers, the red badges of contractors, and the green badges of the interns.

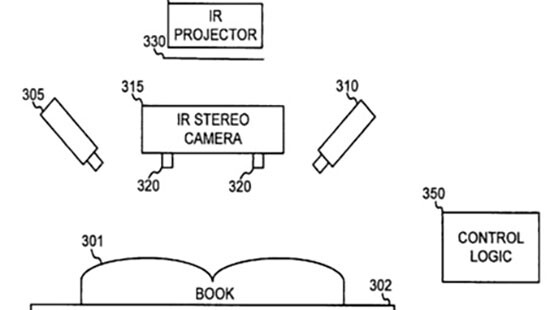

I started to obsess a little. I mined all the information about the yellow badges that I could from Google’s intranet, which led me to the internal name for the team—ScanOps. This class of workers, who left the building much like the industrial proletariat of a bygone era, actually performed the Fordist labor of digitization for Google Books—“scanning” printed matter from the area’s university libraries page by page on V-shaped tables with two DSLR cameras mounted overhead. I found some vague meeting notes, probably left visible by accident, about how they would be excluded from all standard privileges like cafes, bikes, shuttles, and even access to other buildings. This was a fairly commonplace result of hierarchical organization at a corporate multinational, but why was this class of workers denied the privileges that even the kitchen and custodial staff had access to, and why did it seem so secretive?

I researched the Lumière Brothers, who presented their workforce in motion as it left a single gate of their factory that produced photographic plates. It was one of the first films ever made. Almost immediately, I wanted to create a similar document, but updated for the intervening century in digital, high-definition color video with sound. And I wanted to contrast the movement of the Google book “factory” workers with other classes of employees to demonstrate how corporate hierarchy scripts different forms of movement. I also wanted to get to know the ScanOps workers, and see how they felt about all this.

One day during lunch I set up a camera and tripod in a few places around the center of campus and recorded white, red, and green badged employees coming and going. The next day I set up in front of the ScanOps building right before the workers’ shift ended, and recorded their exit. The day after, I sat near the Google sign outside the building and introduced myself to a few of them, offering my card and saying that I worked next door and would love to hear more about their work. The following day—almost a year into working at Google—I was fired. Management would say it was for using company video equipment on company time for a personal project. Google’s legal team would say it was for snooping around the legally contentious Google Books project. But I knew the truth. Because, for all the perks, for all the fountains gushing in the sunshine and the embroidered fleece jackets, the on-site medical staff, the flexibility and the ball pit; for all the “don’t be evil” and the free email and the building of accessible infrastructure for the international democracy to come; for all of this, Google remains committed, first last and always, to accumulation. And that means it wasn’t going to let a little thing like structural racism slow its roll. The yellow badge signified “not worth the price of integration,” considering the high turnover rate, the accounts of physical attacks between employees, the criminal records, the widespread lack of credentialed education. It meant getting paid $10 an hour, going to the bathroom only when a bell indicated it was permissible to do so, and being subject to a behavioral point system that could lead to immediate termination, for which the only fix was at special events like the Easter egg hunt, where a small number of eggs contained point removal tickets. Any attempt to draw attention to the fact that this supposedly revolutionary company contained a decidedly unrevolutionary caste system would be dealt with in the old-fashioned way.

The termination of my employment came at an opportune moment. San Francisco was the first truly cosmopolitan place I’d ever lived. After growing up in a cul-de-sac carved into a forest in Massachusetts, I was noticing that the freedoms afforded to artists like my roommates at Artists Television Access were more appealing than the logistic approaches of documentary, activism, and corporate branding and communications. I was picking up ways of framing my documentary and activist work as “social practice” and “relational aesthetics.” In 2009 I ended up at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the sculpture department. I read the postcolonial theory of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and the constructivist anthropology of Bruno Latour and wrote artist statements where I diagnosed my art like a fascinating new disease, complex and evolving:

My current practice investigates the inner workings of corporate globalization via a direct involvement with the actors, technologies, and organizations that constitute it. In creating this interdisciplinary work, I push the limits of business relationships to extremes that create ruptures and require them to be rethought.

I was quite affected by an idea from The Practice of Everyday Life by Michel de Certeau—“la perruque,” which translates to “wig.” It’s a tactic for enacting resistance in a way that looks like you are just working hard, and what he describes operates more like a computer virus infecting a vast computer program than a revolution.

Independent from coursework, I was reading the blog of San Francisco–based author, entrepreneur, angel investor, public speaker, Chinese kickboxer, tango champion, and lifestyle designer Timothy Ferriss—a shell-company in the flesh. His book The 4-Hour Workweek promoted the outsourcing of tedious tasks to remote personal assistant services in India. I wanted to develop a direct relationship with a member of a corporate middle class subjected to digital sweatshop labor, so I signed up with the service Get Friday in Bangalore. I was paired with a twenty-five-year-old assistant named Akhil. Instead of the Robinson Crusoe, master-slave narrative the company was arranged to reproduce, I paid Akhil to assign me tasks of his devising that, thankfully for the art’s sake, proved to be playful, biographically loaded, and unnecessary. We started by taking our pulse rates and simultaneously charting them in Microsoft Excel. Then Akhil asked me to make a video for him about the best fighter jet in the world. He was a frequent visitor to airshows with his father. I responded with a thirty-three-minute video essay. A promising engineer at an early age, he snail-mailed me pencil drawings of toy boats he had designed and asked me to construct one out of hobby parts and then mail it back to his office. I applied for a Fulbright scholarship to India that would allow me to meet Akhil and produce an exhibition in Get Friday’s offices. My application described the outsourcing relationship as a fluid material that I sought to change the flow of. The Fulbright committee in India rejected it on the grounds of it not being art. Eventually the CEO of Get Friday started to use my project as marketing material to illuminate the company’s progressive corporate values.

Near the end of my studies, I attended a Scholarship Intensive at the Banff Center, a Canadian institution dedicated to the arts, leadership development, and mountain culture. There, I was convinced by a Canadian lawyer to release my Googleplex video, which I had been sitting on for two years because of the nondisclosure and employment termination agreements I had signed. He claimed that because Google Books was already such a legally contentious project when it came to copyright law, and because he imagined many viewers would respond with commiseration, Google wouldn’t pursue legal action against an individual with nothing to lose. I took his advice. My eleven-minute drab-core video essay was played over eighty thousand times on the day Gizmodo and Gawker picked it up.1 Google never responded. Its only public statement was a now-deleted tweet by Marissa Meyer, vice president of Product Search at the time: “Interesting perspective,” she wrote, and linked to the video.

Suddenly I had entered the cottage industry of critical art. I had teaching jobs, invitations to speak publicly, and residencies lined up. I won a $20,000 Dedalus Foundation grant and lived off it for a year after school. I moved to New York and presented at conferences alongside artist-activists like Hito Steyerl and showed in exhibitions with Harun Farocki. I met the curator Aily Nash and our conversation about the Googleplex video turned into a curatorial project—Dream Factory/Image Employment—that showed at museums around the world. Aside from a few freelance gigs and some Airbnb hosting, I was able to spend most of my time with my work. People like Akhil in Bangalore and the workers at Google felt further away. I was surrounded by people who agreed with me, or veiled their minor disagreements behind polite professionalism.

Hankering to make more videos, I had grandiose ideas that would require a lot of capital. If I could lure “big picture” Silicon Valley investors—the types that wanted to live forever, or abolish capitalism (or maybe just Google)—I could make that process of seduction part of the endeavor and really wow my audience with layer upon layer of conceptualism. So I started an art project disguised as an actual creative agency called SONE that formalized my economic activity as a contractual laborer, and this process became artistic content. With the help of a few advisors—entrepreneurs themselves—I formulated an executive summary where I described my startup like any other agency trying to distinguish itself:

Our core function is to serve global markets of communicators in advertising, business, art, and journalism with high quality, pre-trend stock photo and video clips that circulate both on the art market and the stock media market through sites like Getty Images. These clips are based on the idea that current offerings of stock imagery through those marketplaces typically present a limited scope of activity, situations, and identity stereotypes. SONE seeks to create alternative representations of finance and business.

Rather quickly the system I had devised became a trap. Not only did I have to make videos that represented economic discontent and uncertainty while fulfilling Getty Images’ guidelines, I had to develop and maintain an unincorporated and severely understaffed business while avoiding parody. The few Silicon Valley investors I spoke with never took me seriously.

After a year of developing the project I was offered a show by Stephan Tanbin Sastrawidjaja at his gallery, Project Native Informant, in London. Since then about half of his program has grown to consist of artist projects like Shanzai Biennial, GCC, DIS, and ÅYR that, similarly to SONE, blur the distinction between commercial and artistic production. The day before the opening I looked around at the videos in the show and at the “Risk Prevention Investment Objects” whose sales would be used to sustain SONE. I had designed a bunch of conceptual art objects into existence as stand-ins for a rhetorical argument. A gap existed between the works sitting in the gallery and what the work was “about,” which was all the invisible processes—the labor of my collaborators, Getty’s process of content approval—running through the work before, during, and after its presentation. In a way, I still felt like I was producing content for Google, but in an even more myopic hall of mirrors. For trained viewers, an engraved private jet windshield might cause a giggle and perhaps a delusional belief that something out there, beyond that gallery in London’s Mayfair district, beyond the art world, was changing. But I just saw a clever snack for the already converted. Meanwhile, the real action of production and consumption chugged along, as one billion obese humans were seduced into pouring flesh-and-bone-dissolving syrups into their bodies as they burned across vast deserts of asphalt. To actually compete with the thousands of other businesses creating stock imagery, it would mean that SONE wouldn’t be art at all anymore, but rather business as usual.

I flew to Switzerland a few weeks later to do an Art Basel Salon panel with the curator Melanie Bühler and artist Christopher Kulendran Thomas. I was paid 500 CHF for about fifteen minutes of talking, during which I delivered SONE’s investment proposal to an audience of curators and artists. Christopher talked about his new project Brace Brace (with Annika Kuhlmann), which uses the art market to sell unique luxury goods like life rings for yachts that are at once satirical, metaphorical, and functional. Afterward I used my VIP card to get a free ride in a new BMW 7 Series to the Schaulager museum in Newmünchenstein. I pored over the solo show of American artist, writer, and activist Paul Chan—whose work included a map of the 2004 Republican National Convention for protesters and an animation starring the likenesses of filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini and rapper Biggie Smalls that wove together Francisco de Goya’s etchings and a Samuel Beckett play. The careful distinction Chan made between art and activism back in 2008, which had bothered me then, suddenly seemed vital now.

I went home to New York, feeling the buzz of attention and opportunity before slipping into a miasma. I wrote a conspiracy theory with my then-mentee Jane Long, a RISD MFA student. Our theory detailed how the economist Friedrich Hayek had been inspired by his colleague Ludwig von Mises’s Chow Chow to transform the breed into a symbol of neoliberal economics at the inaugural meeting of the Mont Pelerin Society in Geneva in 1947. The text required strenuous research to flesh out the economic theory, history, and policy around the effortless, self-regulating beauty of the Chow—one of the first known dog breeds—and their emergence in ancient times from a spontaneous order possible only through a “free and competitive” wilderness without human intervention. I became frustrated and gave up. I wanted to make things that didn’t require a viewer’s rationalization and instead just haunted them. I started to revel in morbid anxieties and developed quite intuitively a new type of work—objects—centered on questions of absence, inaccessibility, and bodily traces.

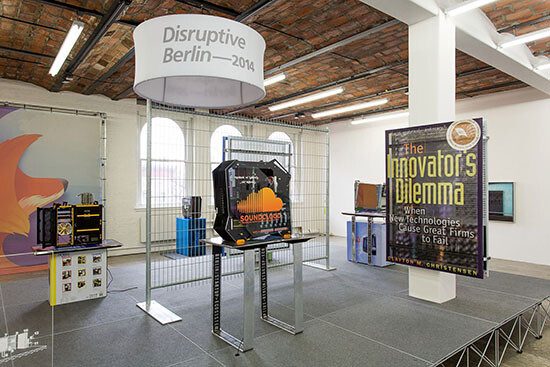

The following spring, right before leaving New York for a six-month fellowship premised on a continuation of my Google-related work, I went to MoMA PS1 for Simon Denny’s show “The Innovator’s Dilemma.” Several projects—three years worth of work—appeared within the modular architecture of a tech-industry tradeshow. Ken Johnson described the show in the New York Times as an attack on the “irrational exuberance about technology” executed with “sardonic verve.” It “indirectly damn[ed] the high-end art market’s own inflationary mania.”2 In the “Disruptive Berlin” section of the show, the most fetishistic of custom computer cases were assembled as intended, except for a few visual embellishments to emphasize components that looked particularly exotic. They displayed the iconography and slogans of “top” Berlin startups like Soundcloud and Sociomantic and were platformed on sleek flat-panel TVs supported by plinths that were actually the boxes of the custom computer cases. Nearby sat empty server racks like the ones that Denny would use, later that year, as display cases for digital files rematerialized from NSA servers in the New Zealand pavilion at the Venice Biennale.

The show felt like a Best Buy feels. I tried to rationalize why those objects were in that museum, and why they were arranged in that manner. Because these containers, meant to encase flows of information, could also serve as framing devices for a materialization of the aforementioned branding? And this is, conveniently, what conceptual art looks like five generations later? Or was it that these massively distributed forms, through their customization, are now rendered as unique objects for another market—one oriented around materiality and a connoisseur’s possession—and “critical” participation is often measured only in terms of how self-conscious of it you are?

I sat on a corporate event platform and looked at large stretched canvas prints of speakers and pull-quotes from Berlin’s 2012 Digital-Life-Design conference, all presented to look like the user interface of Apple’s iOS 6. The work was asking me to process it as knowledge, and I felt as though I was one of the few thousands on this Earth trained to read it holistically. But the reading didn’t seem oriented towards my experience of it, or where this might take me, but rather towards the author, the innovator, the successful artist-as-anthropologist. It seemed that if one actually cared about the politics of information—how digital files both matter and materialize conditions that exclude other ones from mattering—one might get more out of the work of Laura Poitras, who exploits the popular documentary format to generously deliver information of such urgency at much higher stakes. Feeling as if I had spent too long of an evening after work in a big box retail store, I waded through the crowd of art professionals towards the exit.

Outside PS1, another male artist praised the work for its nondidactic qualities and how these allowed the viewer to form their own opinions. My eyes rolled, gesturing towards the VW Dome with the flail of a lanyard cobranded by Denny and Genius, the trendy “online knowledge” startup. “Such affection you have for an ambitious male artist opportunistically piggybacking on the tech sector to tell an already-initiated audience ‘the artist is kind of like a brand!’” Inside the dome an integrated advertising spectacle unfolded through live annotation demos and a panel that included artist/creative director Ryder Ripps and artist/Instagram-personality Nightcoregirl. My companion seemed surprised at my contempt; we had shared enthusiasm for Denny’s work in the past. “Damn. Does this mean you’re giving up a career in corporate art?” he joked. I softened. “It just seems like Simon’s state-and-finance-capital-sanctioned urges to stage his subjects as documentary have suppressed what he’s actually quite good at, which is sculpture.” My friend seemed relieved by this substitution of formalism for vitriol. We reminisced over the strangeness of Denny’s generatively dumb Deep Sea Vaudeo work and that bonkers show in Aachen with the nautical rope.

I landed in Germany for my residency at Akademie Schloss Solitude, which is situated in an eighteenth-century Rococo Schloss in the forest on the outskirts of Stuttgart. Castle rent was covered and I was to be paid €1200 per month on top of a €4200 production budget for whatever I wanted to make. I began to breed mosquitos, write a letter to Bill and Melinda Gates, and create a 3-D model of Baby Sinclair from Jim Henson’s animatronic family sitcom Dinosaurs. My entire production budget would go towards a video celebrating the existence of 3-D models of a mosquito, an oil derrick, and a syringe in a manner similar to the Romantic ekphrasis of John Keats’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn.”

I’ve been trying to articulate what I want out of art since dropping the varied endgames of 21st century social realism. It seems to me that the good gets going through a constant “evolution” of attitudes via experimentation, literally like the evolution without “progress” of webbed feet in ducks. There’s no teleology there, as webbed feet weren’t arrived at for any sort of reason; it was an accident. Marx wrote fanmail to Darwin about this. So perhaps a progressive approach to commercial processes would be more like Death taking you by the hand at the best Sheryl Crow concert you’ve ever been to and realizing that it’s hard to hold on because Ring Pops adorn each finger bone. And then figuring out a way to renegotiate the conditions.

I’m not trying to say I feel particularly liberated as an artist with ideas like this. I’m still romping around in the same hollow plastic Little Tikes play version of society (the art world), staffed largely by delusional incompetents and monitored by horny, neglectful dads. I’ve thought about buying a boat and learning how to fish so that I could eat the sea and drink the rain, free from the obligations of a rented apartment and an occupation. I’ve thought about investing in my future by saving and owning, instead of sleeping in living rooms and unfamiliar beds all just to display things that no one can use. But I keep waking up with the feeling that there’s something to that uselessness. Not a point really—more like a knot. If being a person means being paranoid that you might be a puppet of some other force, like economic networks or algorithms or genetic coding, then being an artist means making things that defy that paranoia. It’s not that there’s no reason; ideally art takes a step beyond reason, towards what ought to be. To create disturbances in the seemingly natural order of things and unwind our counterfeit intuitions.