“We strike art in order to liberate art from itself.”

—MTL1

In the fall of 2008, at the height of both the electoral season and the global financial crisis, a sprawling exhibition entitled Democracy in America was set up by the public arts organization Creative Time for one week inside the Armory building on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. The title of the project at once ironized de Tocqueville’s infamous celebration of the “exceptional” nature of US political culture, while also alluding to Group Material’s groundbreaking Democracy counter-exhibition staged exactly twenty years earlier, with Dia Center for the Arts.

The centerpiece of Democracy in America was what curator Nato Thompson described, drawing on the lexicon of alter-globalization culture, as a “convergence center” in the gigantic training hall of the building. The hall featured murals, installations, performances, projections, a modular amphitheater, and even a cooperatively funded “soup kitchen” by the Alternative Transmissions and INCUBATE collectives in the midst of which left intellectual luminaries such as David Harvey would lead free-for-all seminars regarding the then-unfolding crisis.

Democracy in America also distributed several satellite projects throughout the country, including a series of “town hall” meetings among artists and activists in Los Angeles, Chicago, New York, and Baltimore concerning the meaning of democracy in the current historical conjuncture. Among the art projects was Mark Tribe’s Port Huron Project, which involved the site-specific performative reenactments of iconic New Left speeches by Cesar Chavez, Howard Zinn, and Angela Davis, as well as Valerie Tevere and Angel Nevarez’s Another Protest Song, a participatory archival project concerning the affective connections between popular music and protest that culminated in a “sing out” karaoke party at Flushing Meadows park. Another such commission was a work by Sharon Hayes entitled Revolutionary Love, in which the artist assembled groups of radical LGBTQ people to collectively recite oblique first-person love poems on site at both the Republican and Democratic national conventions in the summer of 2008, highlighting both the heteronormative parameters of mainstream US political culture and the subversive joy of queer collectivity.

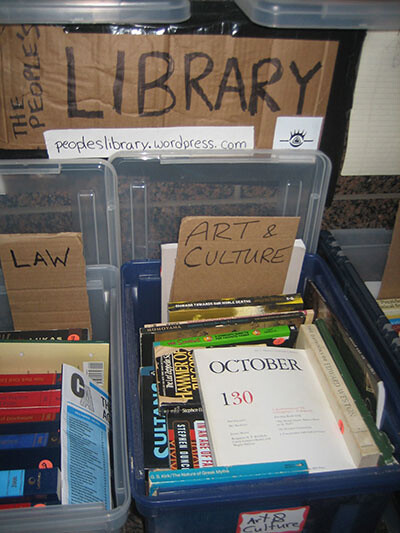

Democracy in America was conceived as a kind of organizing project in its own right, aimed at creating what Thompson called an “infrastructure of resonance” that could facilitate living connections and encounters between different groups sharing an anticapitalist ethos at odds with the prevailing democratic imaginary of the time, which was dominated by the mass mobilization of mainstream progressive groups and so-called millennials in the service of the Obama campaign.2 Democracy in America presented a compelling counterpoint to those who still invested hope in the exhausted US electoral system, and indeed, the publication for the project includes the voices of many artists who would go on to work in the Occupy milieu three years later, including 16 Beaver, Not an Alternative, and Josh MacPhee of the Justseeds collective. Democracy in America was able to stage this critique in a highly mediagenic fashion, receiving an enthusiastic review and video profile from the New York Times and lending an authentically progressive edge to the otherwise modest self-presentation of Creative Time as a promoter of civic dialogue and engagement.3

Nevertheless, the aspirations of Democracy in America remained confined to—or one could say protected by—the discursive space of the exhibition, with the flagship “convergence center” at the Armory functioning as refuge and incubator on the one hand, and simulacral substitute on the other. There was still no movement, let alone revolution, into which the growing radical energies of artists could be channeled in the face of the intensifying crisis of global capitalism.

The second large-scale exhibition project by Thompson for Creative Time was Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art, 1991–2011, mounted in the summer of 2011. Living as Form presented scores of projects from the US and around the world combining experimental artistic tactics with education, research, and NGO campaigns in a format somewhere between bazaar and encyclopedia at the former Fulton Market on the Lower East Side, supplemented by intensive programming of panels, performances, and walking tours. Though designed over the course of the previous two years, the show was installed in the immediate aftermath of the Tunisian and Egyptian Revolutions and the occupation of the capitol building in Wisconsin. Further, anti-austerity protests, riots, and occupations had surged across Europe in the previous years, and the reverberations of the University of California occupations of 2009 were still being felt among radical activists and artists throughout the US. In England, new kinds of “disobedient objects” were being developed, in the midst of student strikes, such as book blocs and paint bombs. Though the Living as Form exhibition was unable to substantially include materials related to the “springtime”4 that seemed to be sweeping the world, it loomed over the series of blockbuster public events that accompanied the exhibition over the summer, in which figures such as Claire Bishop and Brian Holmes were invited to reflect on questions pertaining to the broadly conceived rubric of “socially engaged art” featured in the subtitle of the exhibition, a phrase that seemed to be increasingly embraced by mainstream art discourse to describe a wide spectrum of work drained of any dimension of political antagonism.5

Of particular significance was Bishop’s talk “Participation and Spectacle: Where Are We Now?”There she diagnosed the increasing prominence of phrases such as “dialogical art,” “interventionism,” and, indeed most recently, “socially engaged art” in contemporary art discourse.6 Bishop noted that, whatever their variety, the basic concern of these concepts was to move away from the idea of the art work as a finite object to be perceived in aesthetic terms by an individual understood as “passive spectator.” Instead, the work of art was understood to variously incite, prompt, or provoke the audience in such a manner as to transform it from distanced spectator to full and active collective participant in an open-ended sociopolitical process, performance, encounter, or experience of some kind or another. Whatever their different valences, these discourses took artistic participation as a prefiguration of direct democratic participation.

Bishop made two critical points about this tendency. First, the valorization of social “participation” over finite art work was hardly a novel artistic concern, having taken multiple iterations in twentieth-century avant-gardes, especially those working in proximity to theater and architecture. The desire to destroy the theatrical figure of the “stage” and its implications of distanced spectatorship arguably reached its apogee with the Situationist International, whose work operated outside the confines of the art system and moved directly into—or indeed helped to construct—the radical cultural-political milieu of the French extraparliamentary Left in advance of May ‘68. Bishop’s second point was that “participation” is not a good in and of itself, and that it is imperative to critically judge the quality, both aesthetic and political, of the participation in question. Bishop’s own criteria placed value not on those works that supposedly aspire to create moments of political consolidation in pursuit of this or that goal, but rather on those that stage or bring into relief moments of discomfort, agonism, and failure. Drawing upon one dimension of Jacques Rancière, she suggested instead that the specificity of art is that it can be an arena in which sociopolitical questions are freely staged in unexpected and difficult ways—including ways that question the very meaning of the sociopolitical itself—without the heteronomous burden of goal-oriented political action, which for her is best left to “actual” activists. The danger Bishop saw was twofold. The first was that art could be instrumentalized for external ends, thus destroying its power as a realm of free experimentation. Second was the danger of inflated political claims being made for art in such a way as to compensate for or even substitute for what she sees as a nonexistent Left, claims that for her are in danger of being appropriated by governmental and nonprofit agencies seeking to inject the legitimacy of “civic participation” into their own forms of cultural programming.

A counterpoint to Bishop’s position was provided by Brian Holmes. Complicating Bishop’s conflation of naive ideals of consensus with “activism” per se, Holmes’s remarks at Living as Form reviewed the work of two past groups—Tucumán Arde in Argentina during the dictatorship, and ACT UP in the late Eighties—as offering theoretical models for how art might become a constitutive force in the building of social movements.7 The aspirations of freedom and the avowal of conflict Bishop had valorized as cardinal artistic values were built into the culture of the movements themselves, Holmes suggested. Rather than a unique realm to be protected from either brute instrumentalization or compensatory gestures of participation, art was an essential part of the imaginary and practice of the movements as they engaged in life-and-death struggles involving both antagonistic protest and the affirmative cultivation of new forms of democratic.

In considering the stakes of the exhibition, the weekend of September 23, 2011 deserves pride of place. This was the concluding day of the second annual Creative Time Summit, a massive jamboree of presentations and performances by artists and activists in the style of a TED conference, which, in 2011, overlapped with the programming for Living as Form. Thompson concluded his closing remarks with an exhortation that the audience visit a little-known plaza in the financial district called Zuccotti Park. Zuccotti Park was, of course, the staging ground for something hazily known as “Occupy Wall Street” that had begun a week prior on September 17 and was rapidly gaining buzz in both the mainstream media and the social networks of artists, students, and activists. “Don’t be a spectator, be an agitator!” exclaimed Thompson as the event came to a close. The next day, the participants in a smaller Living as Form event featuring Thompson, critic Gerald Raunig, artist Dan Wang of the Radical Midwest Cultural Corridor, Rebecca Gomperts of Women on Waves, and Dont Rhine of Ultra Red indeed resolved to move the group to Zuccotti Park.

For those steeped in contemporary art theory, walking into Zuccotti Park was an uncanny experience. There, hundreds of incipient occupiers had begun constructing an anticapitalist camp in the heart of the Financial District, transforming a banal, privately owned public space into an otherworldly universe in which the concerns, debates, and indeed fantasies that had so long preoccupied exhibitions such as Democracy in America and Living as Form—protest, public space, democratic participation, decommodified social relationships, collective creativity, radical pedagogy—were being brought to life in all their messiness and difficulty, with a rapid multiplication of global media outlets on site to witness and spread the viral spectacle of occupation. As Dan Wang, who had been invited to speak about his own experience with the occupation of the Wisconsin capitol building earlier in the year, put it, “It was like seeing proof of the multitudes, the array of collective formations, endlessly divisible.”8

In a kind of historical displacement, contemporary art was at that moment thrown into relief as a distant prefiguration or prophecy of what was now happening in real time, too close for the comfort of the exhibitions, conferences, and catalogues within which the radical aspirations of contemporary art had sought refuge. As an historiographical provocation, one that admittedly borders on the eschatological, it might be said that this moment of passage represents the end of socially engaged art. I use “end” here in two senses, neither of which are reducible to simple chronology. First, “end” can mean purpose, goal, or destination, and from this angle, the crossing of the threshold from Creative Time to Zuccotti Park was arguably the realization or consummation of the deepest dreams and desires of the exhibition itself. Yet “end” can also mean completion, termination, or even death, and in this sense the trip to Zuccotti Park might be considered a kind of self-destruction on the part of Living as Form, which had arguably represented the vanguard of contemporary art in the institutional art world—a vanguard defined by its very flirtation with dissolving the category of art altogether into an expanded field of social engagement.

It would be a mistake however to see the move from Creative Time to Zuccotti Park as a move from the realm of “mere” art to the immediacy of “real” life. As we shall see, the OWS encampment itself would be widely described as a surreal environment—“a strange and fabulous land,” as Michael Taussig would later put it9—and many artists would be counted among its initiators, including some who had worked in the orbit of Creative Time projects like Democracy in America and Living as Form itself.

Key among those would be the duo of Ayreen Anastas and Rene Gabri, known for their facilitating role at 16 Beaver in Lower Manhattan and for works such as Camp Campaign (2006). In the latter, the artists undertook a summer-long psychogeographic détournement of the settler-colonial genre of the road trip, travelling around the United States in a van to test out Agamben’s thesis that “the camp is the nomos of the modern” in light of their own question, “How can a camp like Guantanamo exist in our own time?”10 The project comprises a constantly reconfigured archival assemblage of photographs, videos, sound recordings, maps, and field-notes, with the figure of the “camp” as a kind of poetic machine guiding their journey. The artists record their stops at camps and other “spaces of exception” including military camps, homeless camps, labor camps, prisons, immigrant detention centers, Native American reservations, and state parks, as well as the campsites where they themselves slept over the course of their trip. Woven throughout the project are meditations on the relationship of territory to violence, space to power, and life to law, with the camp largely appearing as a site for the exercise of sovereign state power. Yet Anastas and Gabri also highlight sites of biopolitical resistance encountered throughout their journey. For instance, set off against the New Orleans Superdome—which became a horrific refugee camp for displaced black people following Hurricane Katrina—the artists visit Common Ground, a grassroots reconstruction hub run according to the principle “solidarity not charity” in the face of governmental abandonment and disaster capitalism. They also visit a summer camp for young people in East Baltimore run by a former Black Panther in the spirit of that group’s Community Survival Programs, which had been designed to sustain territories of resistance in the face of both economic dispossession and police violence. Recurrent references are made throughout Camp Campaign to Palestinian refugee camps—exceptional spaces that have remained the norm since the mass displacements of 1948, and which bear an affinity to militarized subaltern zones such as East Baltimore.

Camp Campaign aimed to produce a new set of truths about “democracy in America.” It did this not by relying on simple documentary exposure, but rather, as T. J. Demos suggests, through a kind of poetic superimposition of places, histories, and voices that together seem to herald an unknown “coming community” that exceeds the politics of democracy as we know it. Retrospectively, the project stands as an uncanny prophecy of a different kind of camp campaign that would unfurl several years later at Wall Street, the symbolic epicenter of empire itself.

***

Facing up Broadway at the north end of Bowling Green Park in Lower Manhattan, there stands the monumental bronze sculpture Charging Bull. Measuring eight feet tall and sixteen feet long, the bull receives thousands of tourist-pilgrims every week, who line up to take their picture with the iconic sculpture. They often assume comic poses and gestures appropriate to the cartoonishness of the object; shots involving the hypertrophic testicles of the animal are among the most popular. The sculpture is reproduced as an image ad infinitum on T-shirts, postcards, and miniature replicas throughout Lower Manhattan, alongside those of the Statue of Liberty and the Twin Towers, kitschily embodying the swaggering self-mythologization of Wall Street.

Ironically, though, the sculpture was borne not from the self-assuredness of Wall Street, but rather from the global financial crisis of 1987 enabled in part by the neoliberal policies of Reagan and continuing the dismantling since the 1970s of the regulatory oversights imposed on the financial system during the postwar Keynesian system. Mainstream media channeled popular outrage over the crisis to “bad apples” and “crooks” on Wall Street, while in mass culture, Oliver Stone’s indictment of Wall Street in the 1987 film of the same name would end up inadvertently lending it a kind of cinematic allure in the figure of Gordon Gekko and his infamous soliloquy to “greed” as a world-historical force of creative destruction.

On December 16, 1989, without official permission, a little-known Italian artist named Arturo Di Modica had the three-ton bronze object ceremoniously delivered to the site of the iconic Wall Street Stock Exchange as a gift intended to “celebrate the power and endurance of the American people.” Though the object was summarily removed, it was, claimed the New York Post, “beloved” by Wall Street workers and ultimately re-sited at its current location by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation as a “temporary loan to the city.”11

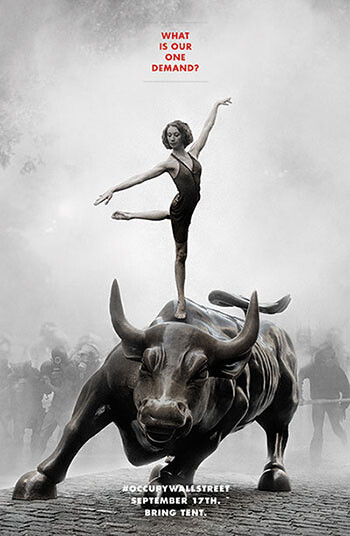

From its first installation in 1989 to the summer of 2011, Charging Bull was thus by and large a quaint tourist attraction, a mascot for the finance industry, and a grotesque market-populist work of “public art” devoted to celebrating the ethos of private profit. But in July 2011, it took on a new life when its iconic power was turned against itself in what would become the foundational meme of Occupy Wall Street (OWS) released by Adbusters. In the famous image, a ballerina stands atop the sculpture in an arabesque pose, her lithe, linear figure playing off against the lumbering bronze corpus of the bull. In the background, hordes of gas-masked militants surge forward toward the viewer through clouds of teargas. At the top of the image, at the apex of the ballerina’s pose, we read “What is Our One Demand?” At the bottom, against the cobblestones of Bowling Green: “#OCCUPYWALLSTREET SEPTEMBER 17TH. BRING TENT.”

The Adbusters image descends directly from the visual culture of the alter-globalization movement, especially the signature aesthetic device of collaging together carnivalesque absurdity—a ballerina surfing the inanimate icon of the Charging Bull—with those of anticapitalist militancy—throngs of gas-masked protesters who seem to have been displaced from the streets of Seattle in 1999 or Quebec in 2001. Recalling the cover of We Are Everywhere, the image evokes Emma Goldman’s famous (though apocryphal) dictum, “If I can’t dance I don’t want to be part of your revolution.”

Yet even as the image clearly channeled the legacy of Seattle, it also resonated with images emerging from the autonomous struggles unfolding across the world over the preceding years at the University of California (UC) and in London, Tunisia, Egypt, Greece, Spain, Wisconsin—the Global Springtime that, the poster seemed to prophesize, would soon be returning home to roost at the symbolic epicenter of the crisis.12 A crucial feature of these struggles that made them distinct from the earlier alter-globalization protests was the tactic and discourse of occupation—a commitment to collectively seizing space (a school, a factory, a square) and staying put physically rather than staging a one-off act of protest against, for instance, a mobile trade summit. Specifically, the transitive injunction to “Occupy” was taken from the UC struggles of 2009, where “Occupy Everything, Demand Nothing” was an essential rallying cry. The more militant elements among the UC occupiers combined this injunction with an analysis of “communization.”13 More than simply a protest demanding this or that finite reform, occupation from this angle involved the blockage of official flows and functions in order to reappropriate time, space, and resources for the reproduction of collective life against the relationships of the wage and private property. Thus, holding space per se is not an end in and of itself, but it provides a base of operations from which to expand and deepen the struggle beyond its immediate site. This combined movement of occupation and communization would also inform the occupations of The New School in New York in 2008–09, many participants in which would go on to work within the early phase of OWS two years later (and would stage a short-lived reoccupation in November 2011).14

The Adbusters call to “occupy Wall Street,” however, emphasized an element that had not come to the fore in the UC system, namely, the figure of the outdoor collective encampment that had captivated the world during the massive occupation of Tahrir Square in early 2011. Protest camps, of course, have a long and varied history, ranging from Resurrection City set up by the Civil Rights Movement in Washington, DC, to peace camps, border camps, and climate camps staged in the following decades around the world.15 Tahrir took this phenomenon to a hitherto unknown scale and level of intensity. It functioned simultaneously as an aesthetic spectacle, a mode of physical self-defense against the state, a living infrastructure of social reproduction for its participants, and a prefigurative zone of common life at odds with the oligarchic and authoritarian order it was opposing. These combined functions made it the territorial nucleus of revolutionary power, what Badiou would call an “evental site,” whose logic would be replicated and translated with different inflections at different sites in the following year.16

The figure of the camp, as we have seen, was central to Ayreen Anastas and Rene Gabri’s Camp Campaign. The home base of Anastas and Gabri’s practice over the prior ten years had been 16 Beaver, a collectively run discursive platform housed in a dingy light-industrial building directly adjacent to both the Stock Exchange and the Charging Bull sculpture. Throughout the 2000s, 16 Beaver was an essential political crucible for New York City. It mediated between the left-wing tributaries of the art system and academia, radical activists of various stripes and generations (especially of the autonomist and anarchist persuasion), and a never-ending flow of friends and guests from around the city, the country, and the world. Many of the latter were first encountered by Anastas, Gabri, and other participants in the collective such as Pedro Lasch, Malav Kanuga, Jesal Kapadia, Matt Peterson, Scott Berzofsky, Brian McCarthy, Amin Husain, and Nitasha Dhillon during their own peripatetic travels to Europe, Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America, oftentimes enabled by invitations from art institutions as well as by some participants’ own complex diasporic connections to places like Palestine, Armenia, Germany, Mexico, and India. 16 Beaver was thus a kind of shadow-formation to the anxious handwringing by art critics about the “nomadic” quality of the global art system at the time, tactically using the latter to build a dense network of connections anchored site-specifically in the autonomous space of 16 Beaver itself.17 The tropes of borders, flows, and networks that were often irritatingly ubiquitous in global art discourse in the 2000s took on a profound significance at 16 Beaver, which became a cosmopolitan incubator for what Hardt and Negri called at the time “a democracy of the multitude.”18 Taking as a theoretical touchstone Walter Benjamin’s ruminations on the importance of story-telling as a practice of intergenerational memory and trans-geographical imagination, 16 Beaver brought people together to collectively speculate about what revolution might mean beyond the nation-state, under conditions of capitalist crisis, exhausted representational politics, and imperialist war—not least in New York City itself.19

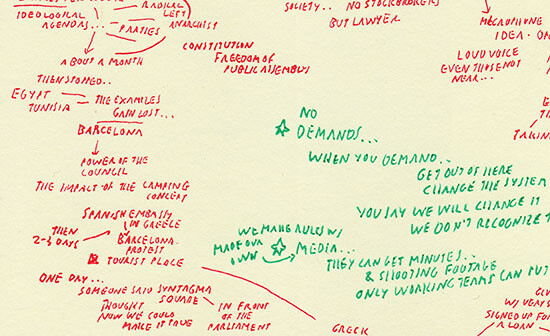

The summer of 2011 was an especially fertile period at 16 Beaver. A series of open seminars with George Caffentzis, Silvia Federici, and David Graeber on “debt and the commons” took place alongside report-backs—in-person and via live stream—from friends involved with the “movement of the squares” in North Africa and Europe. Along with recording these conversations by conventional means for the voluminous electronic archives of 16 Beaver, Gabri and Anastas also followed their custom of transcribing their own notes by hand in real time. The notes from these sessions far exceed mere transcription, instead appearing as gracefully calligraphic maps that track the multidirectional vectors of collective thought as revolutionary energies were transmitted from evental sites elsewhere—Tahrir, Puerta del Sol, Syntagma—into the minds and bodies of those present at the Lower Manhattan space. As our eyes travel across the pages of these notebooks, we follow uncannily prophetic ruminations on crises, camps, assemblies, demands, communities, alliances, fractures, affect, media, police, and beyond.

It was thus no surprise that 16 Beaver would be especially receptive to the Adbusters call to “occupy Wall Street” issued in July of 2011, particularly given the regular presence of Spaniards recently arrived from the M15 movement in Madrid.20 In a little-known text from July 31, 16 Beaver participants from the US, Spain, Greece, Argentina, India, Japan, and Palestine issued a collective statement “For General Assemblies in Every Part of the World,” keying it in turn to a call put out by an anti-austerity coalition called New Yorkers Against Budget Cuts to assemble on August 2 at the Charging Bull sculpture. The coalition involved labor, community groups, and radical students who had been inspired by the movement of the squares, with some of its members having previously set up a small sleep-out camp at City Hall called Bloombergville, an historic reference to the self-organized Hooverville shantytowns set up by homeless and unemployed workers throughout the United States during the Depression.

On August 2, those arriving at the bull found a permitted rally organized by sundry left organizations, with specially authorized speakers using a PA system to address a crowd that had been arranged in the form of an audience watching an actor on stage. Fatefully invoking her experience with radical democracy in Greece during the anti-austerity uprisings of previous years, performance artist and 16 Beaver denizen Georgia Sagri disruptively announced that a true “general assembly” would take place a few yards behind the bull. Rather than a stage with speakers, the assembly simply involved a group of ten to twelve people sitting in a circle on the ground and speaking to one another about what might be possible to do in response to the Adbusters call—a conversation that would evolve over the subsequent month into the full-fledged plan to set up camp a few blocks north of the bull at Zuccotti Park.21

Aside from its sheer interest as an historical anecdote, the story of the founding assembly is of special importance in bringing forth the artistic resonances of Occupy. Not only was it launched from a para-artistic space (16 Beaver) and held at an aesthetically charged site (Charging Bull, reframed by the Adbusters poster), but it was inaugurated with a call from an artist (Sagri) to desert the representational space of the stage, with its spatial hierarchy of speaker and audience, its dependence on official state permission, and its recycling of ideological incantations from left organizations that seemed incommensurate with the depth of the crisis and the opportunity it presented. Like the camp itself that would be set up in the following month, the founding assembly might be understood as a kind of embodied collage, transposing an alien political form into both the ossified landscape of the New York Left and the symbolic heart of global capital itself.

Further, the “horizontal” logic of this political form—a refusal of the stage in favor of “direct” democracy—tapped into a long-standing anti-representational impulse leading from Rousseau to Bakhtin to Debord of refusing politics qua theatrical spectacle in favor of immediate and full participation. As we have seen, “participation” was an essential concern of much contemporary artistic discourse at the time, yet its frequent conjugation with ideals of immanent consensus had been challenged by critics like Claire Bishop as regards the “quality” of participation—who participates, how, to what ends, and through what aesthetic means? To be sure, none of the participants imagined the inaugural assembly as an artistic intervention, and “art” as a horizon was irrelevant at the time. But the assessment of the event from an artistic angle throws into relief certain exemplary aesthetico-political antinomies that would structure Occupy as a whole: spectacle and participation, consensus and dissensus, consolidation and division. Though it would give rise to what would become a spectacle of democratic inclusion, it is important to note that the first microscopic assembly of Occupy at Charging Bull began not with harmonious cooperation but rather an act of cutting and separation.

Thus began a began a process in which the Financial District would be re-territorialized, its frozen spaces brought to life in a kind of psychogeographical dramaturgy pitting precarious bodies and communal infrastructures against the architecture of global capital and its violent police enforcers. This anticapitalist gesamkunstwerk, memorably described by Martha Rosler as “a work of process art with a cast of several thousand,”22 would become the crucible for a new avant-garde that in the subsequent five years has at once taken flight from the art system as we know it, while tactically engaging its institutions and resources for the expanded work of movement-building.

The present essay is a slightly amended excerpt from Strike Art: Contemporary Art and the Post-Occupy Condition (Verso). The book treats the eruption of Occupy Wall Street in the fall of 2011 as what Alain Badiou would call a “political truth-event,” one of four such kinds of event whose service as objects of fidelity fundamentally defines the terrain of subjectivity. The ongoing ramifications of Occupy are evident across the spectrum of the Left, ranging from the invocation of the “1 percent” as a general class enemy in the self-described democratic socialist campaign of Bernie Sanders, to the rich debates concerning questions such as the party-form, communization, and platform cooperativism in contemporary theory—all of which have been recoded and radicalized by the emergence of Black Lives Matter.The advent of Occupy has also had deep consequences for contemporary art. First, Occupy was a movement with artists at its core, not just as adjunct decorators, but as organizers, theorists, and propagandists working to articulate their own class composition of indebted, precarious cultural workers with a broader horizon of solidarity with the internally fraught figure of the “99 percent.” Second, the activity of artists in Occupy was decidedly autonomous from the institutions of the art system, even as the latter would become targets of mobilization in their own right by groups such as Occupy Museums, Arts and Labor, GULF, and Not an Alternative. This particular excerpt offers an historical snapshot at the moment of breakage between the institutional art system and the new space opened by Occupy.

Nato Thompson, “Exhausted? It Might be Democracy in America,” in A Guide to Democracy in America, ed. Thompson (New York: Creative Time Books, 2008), 14–25.

Holland Cotter, “With Politics in the Air, a Freedom Free-for-All Comes to Town,” New York Times, September 22, 2008.

See Springtime: The New Student Rebellions, eds. Clare Solomon and Tania Palmieri (Brooklyn: Verso, 2011).

See Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art, ed. Nato Thompson (New York: Creative Time Books/MIT Press, 2012).

Claire Bishop, “Participation and Spectacle: Where Are We Now?” in ibid., 34–55. This text draws on her earlier edited anthology of writings and documents from the twentieth century concerning these questions, Participation (Cambridge, MA: Whitechapel/MIT Press, 2005), and forms the basis for her authoritative summary and critique in Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (Brooklyn: Verso, 2012).

Brian Holmes, “Eventwork: The Fourfold Matrix of Contemporary Social Movements,” in Living as Form, 72–93.

Dan Wang, personal correspondence; also see Wang, “From One Moment to the Next, Wisconsin to Wall Street,” transveral, October 4, 2011 →.

Michael Taussig, “I’m So Angry I Made a Sign,” in Occupy: Three Inquiries on Disobedience (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 3.

See T. J. Demos, “Means Without Ends: Ayreen Anastas and Rene Gabri’s Camp Campaign,” October 126 (Fall 2008): 69–90; Nato Thompson, “Conversation with Ayreen Anastas and Rene Gabri,” in A Guide to Democracy in America, 135–138.

“Bah Humbug: Stock Exchange Grinches Can’t Bear Christmas Gift Bull,” New York Post, December 16, 1989. For a detailed history of the sculpture—including its reiteration in other sites around the world such as Shanghai—see chargingbull.com →.

For a pre-Occupy collection of voices from these global struggles, see Springtime.

See Research and Destroy, “Communiqué from an Absent Future,” in Springtime; also Communization and Its Discontents, ed. Benjamin Noys (Brooklyn: Minor Compositions/Autonomedia, 2011); and especially Daniel Marcus’s “From Occupation to Communization,” Occupy Gazette 3 (December 2011) →.

See Rachel Singer, “The New School in Exile, Revisited,” Occupy Gazette 3.

See Anna Feigenbaum, Fabian Frenzel, and Patrick McCurdy, Protest Camps (London: Zed Books, 2014). The authors focus mostly on European examples, but their analysis of the basic elements of the camp as a “biopolitical assemblage” and “collective infrastructure” is highly relevant to understanding both Tahrir and OWS as something more than a matter of liberal public assembly. For a close architectural reading of the encampment set up by the group Hog Farm at the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, see Felicity D. Scott, “Wood-Stockholm,” in Sensible Politics: The Visual Culture of Nongovernmental Activism, eds. Yates McKee and Meg McLagan (New York: Zone Books, 397–428).

Alain Badiou, The Rebirth of History: Times of Riots and Uprisings (Brooklyn: Verso, 2012).

For an early instance of critical anxiety around the accelerating travel-flows of the global art system, see Miwon Kwon, One Place After Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002).

Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire (New York: Penguin Press, 2004).

Walter Benjamin, “The Storyteller,” tr. Harry Zohn, in Illuminations (New York: Schocken Books, 1968), 83–110. In 2009, 16 Beaver developed a program of events at the New Museum called “Project for a Revolution in New York; or, How to Arrest a Hurricane,” intended to “assemble a possible diagram for a desiring revolutionary machine.”

Andy Kroll, “How Occupy Wall Street Really Got Started,” in This Changes Everything: Occupy Wall Street and the 99% Movement (Oakland: Berret-Koheler, 2011), 16–21. The Spaniards in question were, among others, Luis Moreno-Caballud and Begonia Santa-Cecillia, who would go on to form the Making Worlds working group in Occupy, devoted to theorizing and experimenting with models of the commons.

See David Graeber’s account of the August 2 assembly in The Democracy Project: A History, a Crisis, a Movement (New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2013), 24–30; and Nathan Schneider’s account of the weeks of meetings leading up to the September 17 occupation in Thank You, Anarchy: Notes from the Occupy Apocalypse (Berkeley: UC Press, 2013).

Martha Rosler, “The Artistic Mode of Revolution: From Gentrification to Occupation,” eflux journal 33 (March 2012) →.