Paradise absent is different from paradise lost … 1

A city, perhaps like a person, always exceeds the myth of its origins. It’s not a coincidence that as a cosmopolitan city Beirut became synonymous with loss. It may be impossible to establish the beginning and end of the Lebanese civil wars. They are generally given the dates 1975–1990: from a 1975 assassination attempt on Maronite Christian and Phalangist leader Pierre Gemayel—and the immediate retaliation by his followers against a busload of Palestinians in April of that year—until the 1990 implementation of the Taif Accord and Syrian intervention. Outside of these events, many historians have pointed to the fragile political conditions resulting from a governing system based on religious sects, patronage, powerful families, militias, and, after 1948, an influx of displaced Palestinians as providing the unstable—almost inevitable—conditions for internecine conflict. As journalist Sandra Mackey writes about the war:

At one point it was estimated that no fewer than 186 warring factions representing contending communal identities and ideologies, splinter groups within these larger blocs, and foreign governments pursuing their own interests were battling within a country seven-tenths the size of Connecticut.2

After 1975, this spiraling factionalism transformed the collapsed state of Lebanon into a dense mosaic of heavily fortified neighborhoods and mini-fiefdoms. Perhaps a better date to mark the end of the wars is the disarming of militias, excluding Hezbollah, in the spring of 1991. Yet given ongoing hostilities between Hezbollah and Israel (culminating in their 2006 war), the assassination of ex-Prime Minister Rafic Hariri in 2005, and the scattered sectarian violence of 2008, some would argue that the Lebanese civil wars have never really ended. Unlike many countries recently overwhelmed by internal ethnic, cultural, and racial violence, Lebanon has never had an official truth and reconciliation commission. The length and ferocity of the war left many wanting to forget and rebuild. But as Walid Raad’s art shows, forgetting is another form of remembering, and disaster wreaks havoc with law just as it does without law.

1. Performing the Archive

In the late 1990s, Raad created a fictional foundation called The Atlas Group in order to better organize and more subtly contextualize his growing output of works documenting the Lebanese civil wars. While The Atlas Group may be imaginary, Raad rightfully stresses its very material results.3 Raad produces artworks addressing the infrastructural, societal, and psychic devastation wrought by the wars; he then re-dates and attributes these works to an array of invented figures who in turn are said to have donated these works directly or by proxy to The Atlas Group archive. Regardless of medium, Raad processes and outputs all of his work digitally, thereby adding another layer of documentary intervention to his overarching fictional conceit.

Raad rarely allows materials from The Atlas Group to be exhibited without some form of public presentation. Before his identity with The Atlas Group became more widely known (and even after it did), Raad would present himself as a representative of the foundation lecturing on and presenting other people’s work from the archive.4 An extended question-and-answer session was central to these performances, during which Raad would plant audience queries and comments to help steer the conversation, including in the direction of unveiling the project’s fictional dimension for those who hadn’t deciphered the ruse. This oftentimes involved getting the audience to move beyond their own discomfort with subterfuge in order to engage Raad’s larger concerns: historiography as a process conceived as a concrete series of events; the ways in which archives are formed and disseminated; the effects of personal and collective trauma on memory and its articulation; and the ultimately unspeakable and unrepresentable dimension of the Lebanese civil wars. Each of these, not uncoincidentally, involves the use of fictional devices.

Raad writes:

We do not consider the [sic] “The Lebanese Civil War” to be a settled chronology of events, dates, personalities, massacres, invasions, but rather we also want to consider it as an abstraction constituted by various discourses, and, more importantly, by various modes of assimilating the data of the world.5

In The Archaeology of Knowledge, Michel Foucault famously argued that an archive is a discursive system regulating what can and cannot be said in and about any historical period.6 Much has been made, and at this point maybe too much has been imitated, concerning Raad’s use of fiction and artifice in fashioning his documents of recent Lebanese history. Yet what has sometimes been overlooked by scholars, critics, and Raad’s audience is that fiction was always the means and never the ends. During the course of an interview with Raad, John Menick comments: “The issue of what can and can not be discussed in relation to Lebanon and his immediate context comes up again and again during the discussion.”7 In other words, Raad’s goal is not a counter-memory, but an investigation of the ways in which memory is produced; not a counter-archive per se, but an interrogation of discursive formations constituting any archive as a compendium of present knowledge.

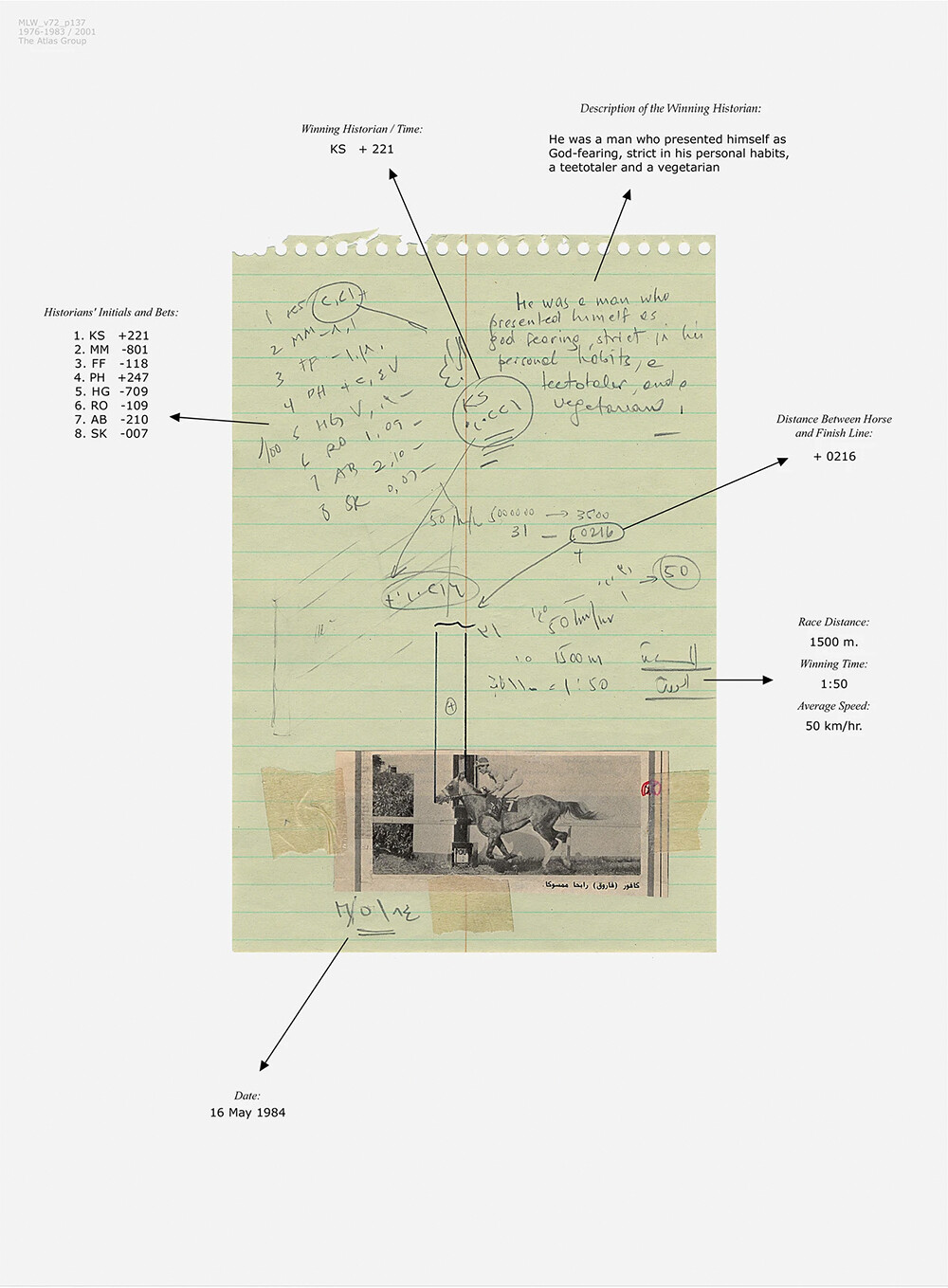

A good example of this approach appears in a project that partly launched The Atlas Group: Notebook Volume 72: Missing Lebanese Wars (1989/1998). (Here and in the following, first dates are attributions by The Atlas Group; the second refer to Raad’s production of the work. Artworks with only one date are not part of The Atlas Group’s “official” archive.) The project reproduces information recorded in a stenographer’s notebook by a “Dr. Fadl Fakhouri” concerning bets waged at horse races by his fellow historians of the civil wars. But rather than betting on the winning horse, these gamblers—including Maronites, socialists, Marxists, and Islamists—wagered on the amount of distance between the horse’s nose and the finish line as captured in the photo-finish image published in the next day’s newspaper.

For Raad, history can never be captured at the moment it occurs—or after. The historians themselves can only estimate the discrepancy between the event and its documentation. Yet their conjecture only compounds the disparity between history and its recording, as no historian manages to guess exactly the distance between horse and finish line; rather, the winner of the bet is the one who comes closest. In other words, Notebook Volume 72: Missing Lebanese Wars deals with how history is written as opposed to actual historical events.8 Rather than writing an unwritten history, Raad’s art aims to write the writing of history.

According to theorist of the photographic image John Tagg, “Photographs are never ‘evidence’ of history; they are themselves the historical.”9 Notebook Volume 72: Missing Lebanese Wars offers a strong critique of historical teleologies and grand narratives. After all, each of the ideologies represented by Raad’s imaginary historians envisions history as fulfilled one day. Raad also renders as fundamentally absurd the trajectory of the civil wars, consequently sapping the myth of Beirut as the realization of Parisian modernity in the Middle East (a self-fashioning story quickly revived after the wars). Fakhouri stands outside all of this as a more skeptical voice. He’s also deceased, his documents having been discovered and bequeathed to The Atlas Group after the fact. Or perhaps it’s more precise to say: after the fact of the fact. The various misdirections in Raad’s work expose the fictional elements in reconstructions of the past (especially personal ones) while undermining the presumed authority—Raad’s own first and foremost—to write a definitive historical account. In his performances as well, Raad assumes in order to vacate—or at least call into question—the notion of official spokesperson.

2. Trauma and Space-Time

Fakhouri’s obsession with temporal gaps and ruptures allows Raad to introduce the notion of trauma that is central to The Atlas Group project. Trauma theorist and historian Cathy Caruth writes:

Trauma is not experienced as a mere repression or defense, but as a temporal delay that carries the individual beyond the shock of the first moment. The trauma is a repeated suffering of the event, but it is also a continual leaving of its site. The traumatic reexperiencing of the event thus carries with it what Dori Laub calls the “collapse of witnessing,” the impossibility of knowing that first constituted it. And by carrying that impossibility of knowing out of the empirical event itself, trauma opens up and challenges us to a new kind of listening, the witnessing, precisely, of impossibility.10

This temporal disconnect combined with an epistemological crisis appears throughout Raad’s work. For example, in two films given to The Atlas Group entitled Miraculous beginnings and No, illness is neither here nor there, Fakhouri is said to have exposed a single frame of film every time he believed the civil wars had ended (in the case of the former work) and whenever he encountered a doctor’s or dentist’s office sign (for the latter) (1993/2002 & 1993/2002). These pieces, less than two minutes in length each, record a hunger for closure and healing while their literally hundreds of discrete images create an at first elegiac and then ridiculous cavalcade of frustrated hope. The desire for simultaneous personal and historical closure is conflated and then rendered sadly comical in Raad’s search to find a way of addressing a past that continually haunts, and displaces, the present.

Fiction is here, and throughout Raad’s work, in the service of an elusive real. “The real must be fictionalized in order to be thought. This proposition should be distinguished from any discourse—positive or negative—according to which everything is ‘narrative,’ with alternations between ‘grand’ narratives and ‘minor’ narratives,” writes Jacques Rancière.11 Resisting the narratives of conventional historiography, The Atlas Group refuses to capture the past and perhaps proposes that hope without closure may be the only kind of hope worth hoping for. Unlike other contemporary Lebanese artists who appropriate and manipulate imagery from the prewar years—such as Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige’s literally burnt and torn postcard series, Wonder Beirut: The Story of a Pyromaniac Photographer (1998–2006)—Raad’s work has almost never depicted an irrecoverable time or geography. Rather, what is lost is continually lost again in the present; it is absent. An exception appears at the beginning of Raad’s very early film The dead weight of a quarrel hangs (1997), where he fetishistically documents a set of small domestic objects carried to Lebanon by a female Palestinian (Raad’s mother is a Palestinian displaced in 1948). But in this case, absence has been precariously internalized within a familial space rather than projected onto a vanished external home.

If some of Raad’s earliest works addressed the end of the war (and its accompanying flickers of hope), he soon began to move backward in time, instigated partly by his interest in the car bomb as a weapon of military conflict and civilian terror. In Notebook volume 38: Already been in a lake of fire (1991/2002), Fakhouri cut out and pasted 145 color photographs of cars identical to ones used as bombs during the civil wars. In handwritten Arabic text, Fakhouri details the day, time, and place of the explosion, along with the number of people killed and injured, the area of the blast, the amount of explosives involved, and a short description of the vehicle. Of the many published print versions of Raad’s work,12 these carefully composed notebook pages reproduce the most directly, and in this sense come closest to contributing to, a conventional history of the civil wars.

At the same time, car bombs are for Raad the paradigmatic destroyers of space-time continuums during the wars, and as such have remained highly charged objects of fascination for him. Lebanese visual artist and theorist Jalal Toufic writes: “What is site-specific about Lebanon? It is the labyrinthine space-time of its ruins, what undoes the date- and site-specific.”13 Although Raad produced conceptual documentary-based work about the Lebanese civil wars for nearly fifteen years, the amount of concrete information pertaining to the conflict that might be extracted from this material would amount to no more than a few paragraphs (excluding facts and details conveyed during the question-and-answer sessions following his performances). What hard evidence does exist is sometimes inconsistent: at one point Raad claimed that 145 car bombs were exploded during the war; he then revised the number to 3,641 (the latter is more accurate). In a civil war characterized by the complete collapse of the state, how is historical knowledge produced and confirmed? Independently, by each warring faction. This is site-specificity taken to its illogical extreme. Confronted with a proliferation of competing realities, Raad (and Toufic in his own art and writing) decided instead to investigate the unreal, ruins, and a spectral sense of place.

The recent wars in Lebanon defy traditional narrative structures such as beginnings and endings, causes and effects, and suffering and redemption. At certain moments—in 1977, in 1983—the wars seemed to be subsiding. Conferences were organized; rebuilding plans were developed; books were published—only to have the fighting flare up again even more brutally.14 After the first few years of the wars, it became difficult to discern whether they were being fought over ideologies or profits. In a series of photographic prints entitled Let’s be honest, the weather helped (1998/2006), Raad mapped out at least twenty-three countries supplying arms to the various militias. Profiteering as a means to eradicate the past intensified after 1991 as rival plans and politicians battled over reconstruction contracts.

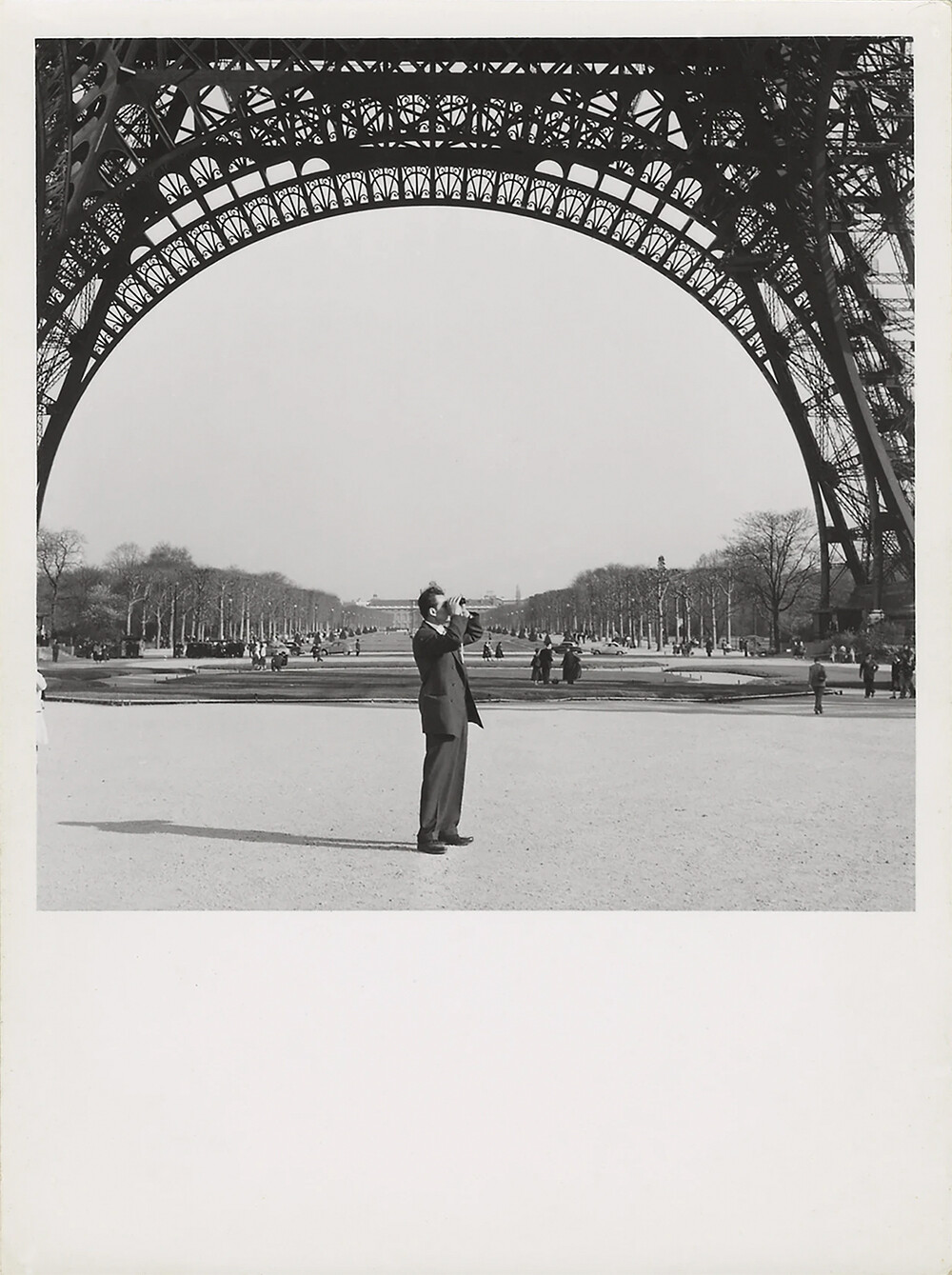

Looking at The Atlas Group project overall, one sometimes wonders whether Raad or Beirut is more haunted by ghosts. Fakhouri has already died when the archive is beginning to be assembled; as a result, his idiosyncratic documents gain in symbolic power what they lose in objective authority. (Fakhouri’s wife and daughter—vestiges of civil society—donated his notebooks, films, and photographs to The Atlas Group.) Yet Fakhouri is mysteriously resurrected near the project’s “end.” Does that make a female presence—Fakhouri’s vanished wife, the early traces of Raad’s mother—the most ghostly figure of all in The Atlas Group? Although Raad still occasionally produced work for The Atlas Group, he has historicized it with the dates 1989–2004. Fakhouri appears in one of its final set of documents: Civilizationally, we do not dig holes to bury ourselves (1958–1959/2003), a collection of twenty-four black-and-white self-portrait photographs Fakhouri made while visiting Paris and Rome in 1958 and 1959. A number of these pictures were taken in front of famous monuments such as the Eiffel Tower and Notre Dame. The bitter irony, as Raad surely knows, is that a person from the Middle East photographing himself or herself near such landmarks in a post–September 11 world would be cause for suspicion or even arrest.

The fact is that these are old photographs of Raad’s father. Thus, The Atlas Group loosely opens and closes with the conflation of fictional and actual father figures, thereby throwing into question the place of this traditional symbolically organizing presence. Rancière writes: “blocks of speech circulat[e] without a legitimate father to accompany them toward their authorized addressee. Therefore, they do not produce collective bodies. Instead, they introduce lines of fracture and disincorporation into imaginary collective bodies.”15 Civilizationally, we do not dig holes to bury ourselves is a primary example of this dynamic and of how certain aspects of Raad’s overall artistic project function: an authority figure is exposed as false while simultaneously being reinserted into the historical record so as to facilitate a disruption (“lines of fracture and disincorporation”) that might allow for a new understanding and experience of history to emerge. A significant family document is depersonalized before being snuck in as disguised autobiography.

An argument could be made that for all of its focus on Lebanon’s recent past, Raad has created a uniquely elaborated and extensive cosmology that rivals in idiosyncratic vision an artist as seemingly unrelated as Matthew Barney. Like Barney’s Cremaster universe, every piece in Raad’s fabricated world has its place; The Atlas Group archive is filled with cross-referenced files that intricately—almost intertextually—relate. Like Toufic’s Beirut, it’s a labyrinth more than a site. Raad’s project is as fantastical as Barney’s imaginary world, albeit more immediately serious in its engagements. This fanciful quality (Raad’s borderline excessively romantic titles are one clue) is oftentimes overlooked by critics and scholars committed to the very solemn discourse—with its geopolitical resonances and institutional ramifications—surrounding the reception of Raad’s art. For this reason, it helps to remember that one of the earliest motivations for Raad’s deadpan performances was as a critique and even parody of the standard artist talk.

As Raad’s current retrospective, Walid Raad (October 12, 2015–January 31, 2016), at the Museum of Modern Art in New York emphasizes, performance has always been a primary component of his work. After mostly concluding The Atlas Group in 2004, Raad turned his attentions to the rapidly burgeoning financial support and institutional infrastructure for art and artists in the Middle East: museums, galleries, art schools, collectors, collections, magazines, curators, critics, and so forth. The result is Scratching on things I could disavow (2007–ongoing). Like The Atlas Group it has numerous component parts, although this time the structure isn’t the documents, types, and files of an archive but the chapters, sections, indices, appendices, prefaces, and even the translator’s introduction of an imaginary book. Mostly concentrated in MoMA’s famed atrium, aspects of this project take up nearly half of the overall exhibition (the other half consists of The Atlas Group materials), and Raad’s Scratching on things I could disavow: Walkthrough talk-performance component is crucial to its full realization, with Raad conducting more than fifty iterations (sometimes two a day) during the show’s three-and-a-half-month run.

Origin stories are purposefully obscured in all of Raad’s work, but one impetus for Scratching on things I could disavow appears to have occurred in 2007 when Raad was asked to join the Artist Pension Trust—an entrepreneurial retirement plan for artists. Curious as much about the economics of the plan as he was about the two hundred and fifty artists from the Middle East who had been invited to participate, Raad began investigating online and in conversation with his international network. What he discovered rivaled The Atlas Group’s collated intricacies and cast of characters, but within a very real hyper-commercialized global art world that finds curators, financial consultants, tech startups, and former members of Israel Defense Forces elite military intelligence units linked with artists willing to donate their work to the Artist Pension Trust with the promise of later receiving a percentage of whatever money the company generates via the sale of the artwork of its members—nearly two thousand in total.

The result of this research is Translator’s introduction: Pension arts in Dubai (2012), a freestanding wall to which Raad has affixed paper cutouts with the faces of key players, names of participates, legal documents, organizational structures within Israel’s military, lines connecting all of these, and swirling flashes of surveillance video. The object serves as a kind of corporate archive, but more importantly it functions as the backdrop for a lecture on his findings.16 The circa thirty-minute performance is the first half of Walkthrough as Raad details the multinational interrelations of culture, finance, military, and technology with his trademark mix of the disconcerting and absurd. Every detail of his presentation might not be entirely factual, but—as with The Atlas Group—the larger allegory holds true: affectively and intellectually. Raad seems to take particular delight in using the phrase “risk management,” an investment field in which one of the Artist Pension Trust’s founding partners specializes, and an oxymoronic notion trumped by the catastrophe of war with its disruption of past, present, and future.

The second half of Walkthrough looks at artworks—Raad’s own and others—and cultural institutions in the Arab world that have been subject to a withdrawal or a refusal as a result of both recent geopolitical catastrophe in the Middle East and the rush by Westerners and Arabs alike to capitalize on the region’s exploding art scene: Raad’s first full presentation of The Atlas Group artworks in Lebanon in 2008 at Sfeir-Semler Gallery—built on the site of a massacre in Beirut in 1976—mysteriously shrunk to miniature (Section 139: The Atlas Group [1989–2004] [2008]); the color red unavailable for use to Middle Eastern artists of the future (Index XXVI: Red [2010]); a freshly constructed museum of modern and contemporary art somewhere in the Middle East that mysteriously blocks a visitor from entering (Section 88_ACT XXXI: Views from outer to inner compartments [2010] and Section 88: Views from outer to inner compartments [2010]). Perhaps most striking—and disturbing—in Raad’s narration is the loss of individual agency accompanying these phenomena as a form of postcolonial post-traumatic stress disorder in a region repeatedly destroyed by war and colonization also subject to economic forces seemingly beyond the control of anyone except oligarchs. Raad describes receiving the information about these works telepathically, and during this part of the performance almost pleadingly inquires of his audience: “I know that some of you have experienced this sort of thing before, and you know that you should never trust telepathic signals.”

Dominick LaCapra, Writing History, Writing Trauma (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001), 57.

Sandra Mackey, Mirror of the Arab World: Lebanon in Conflict (New York: W. W. Norton, 2008), 119.

Walid Raad, “Let’s Be Honest, the Rain Helped: Excerpts from an Interview with The Atlas Group,” in Review of Photographic Memory, ed. Jalal Toufic (Beirut: Arab Image Foundation, 2004), 45.

Before receiving regular exhibition opportunities (and before developing a body of art objects for exhibition spaces), Raad performed The Atlas Group on the European alternative theater circuit and at independent film festivals. His first prominent art-world appearance in the United States, as part of the 2002 Whitney Biennial, was for performance, not the exhibition component.

Raad, “Let’s Be Honest, the Rain Helped,” 44.

Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge, trans. A. M. Sheridan Smith (New York: Pantheon, 1972).

John Menick, “Imagined Testimonies: An Interview with Walid Ra’ad” →. Originally published at bbs.thing.net, March 25, 2002.

It may be helpful to know that “the Palais des Paix is a racetrack like no other. Situated near Beirut’s city centre and divided by the infamous Green Line, the track was a repeated theatre of war … Riddled with bullet holes, the track nonetheless remained intermittently open during the war” (Dina Al-Kassim, “Crisis of the Unseen: Unearthing the Political Aesthetics of Hysteria in the Archaeology and Arts of the New Beirut.” Parachute 108 (October/November/December 2002): 161, n. 6), or that in his foreword to a book detailing his company’s accomplishments in rebuilding Beirut, Nasser Chammaa, chairman and general manager of the construction and engineering firm Solidere (founded by Hariri), boasted, “By the end of 2001, those who had wagered on Beirut city center scored” (Robert Saliba, Beirut City Center Recovery: The Foch-Allenby and Etoile Conservation Area (Beirut: Solidere, 2004), 9). But these are secondary details buried in Raad’s work.

John Tagg, The Burden Of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993), 65.

Cathy Caruth, “Trauma and Experience: Introduction,” in Trauma: Explorations in Memory, ed. Cathy Caruth (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), 10; emphasis in original.

Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible, trans. Gabriel Rockhill (London: Continuum, 2004), 38.

For a compilation, see Walid Raad, Scratching on Things I Could Disavow: Some Essays from The Atlas Group Project (Lisbon: Culturgest; and Cologne: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther Köning, 2007).

Jalal Toufic, “Ruins,” in The Atlas Group (1989–2004): A Project by Walid Raad, eds. Kassandra Nakas and Britta Schmitz (Cologne: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther Köning), 56.

In 1983, the year between the Israeli invasion and a particularly violent stretch in the wars, Raad’s family sent him to the United States to live with a relative. He was also at the age when many adolescents were forcibly pressed into a militia.

Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics, 39.