There is no harmony in the universe. We have to get acquainted to this idea that there is no real harmony as we have conceived it.

—Werner Herzog1In the experience of deep sadness, the world itself seems altered in some way: colored by sadness, or disfigured … [This originates] in desolation, in the sense that the world is frozen and that nothing new is possible. This can lead to terrible paroxysms of destruction, attempts to shatter the carapace of reality and release the authentic self trapped within; but it can also lead away from the self altogether, towards new worldly commitments that recognize the urgent need to develop another logic of existence, another way of going on.

—Dominic Fox2

The Anthropocene is the era in which man’s impact on the earth has become the single force driving change on the planet, thus giving shape to nature, shifting seas, changing the climate, and causing the disappearance of innumerable species, including placing humanity on the brink of extinction. The Anthropocene thus announces the collapse of the future through “slow fragmentation towards primitivism, perpetual crisis and planetary ecological collapse.”3 Instead of being conceived as speculative images of our future economic and political system, the Anthropocene has been reduced to an apocalyptic fantasy of human finitude, world finitude, and the manageable problem of climate change. In the last decade, films about the end of the world have been characterized by an apocalyptic and doomsday narrative that may end with moral redemption—from The Day After Tomorrow (2004), and 2012 (2009), to Lars von Trier’s Melancholia (2011) and World War Z (2013). In parallel, we have seen in the mass media a narrative presenting climate change as a fixable catastrophe, just like any other (such as the 2008 financial crisis, or the 2010 BP gulf oil spill). Neither our condition of finitude nor the world after the human has been imagined, and the massive environmental impact from the industrial era onward, with its long-term geomorphic implications, has become unintelligible.

The Anthropocene has meant not a new image of the world, but rather a radical change in the conditions of visuality and the subsequent transformation of the world into images. These developments have had epistemological as well as phenomenological consequences: while images now participate in forming worlds, they have become forms of thought constituting a new kind of knowledge—one that is grounded in visual communication, and thereby dependent on perception, demanding the development of the optical mind.4 The radical changes in the conditions of visuality under the Anthropocene have brought a new subject position, announced by the reformulating trajectories between impressionism and cubism, and those between cubism and experimental film. While cubism culminated with the antihumanist rupture of the picture plane and converted the visual object, along with surrealism, into “manifestation,” “event,” “symptom,” and “hallucination,” experimental film introduced a mechanical, posthuman eye conveying solipsistic images at the sensorimotor level of perception. The consequence of these developments is that images, as opposed to being subject to our “beliefs,” or being objects of contemplation and beauty, came to be perceived as “the extant.” This involves a passage from representation to presentation, that is, instead of showing a perpetual present in a parallel temporality in order to make the absent partially present, the image has become sheer presence, immediacy: the here and now in real time. Made up of particles of time, wrested out of sensation and turned into cognition, the image deals more with concepts and saying than with intuition and showing.

With its break from the Renaissance point of view, cubism decomposed anthropomorphism. Based on linear perspective, Renaissance perspective had normalized a viewing position as a centered, one-eyed static entity within a mathematical, homogenous space. Creating the illusion of a view to the outside world, Renaissance perspective made the pictorial plane analogous to a window. Images constructed with traditional perspective bestow identities and subjects given a priori, configured by the point of view provided by the picture plane. Cubism, in contrast, turned space, time, and the subject upside down, redefining spatial experience by rupturing the picture plane.5 If classical representation conveys a continuous space, cubism invented discontinuous space by subverting the relations between subject and object, making identity and difference relative, questioning classical metaphysics. The cubist image renewed the image of the world by dissociating gaze, subject, and space, but without estranging them from each other, bringing about a new, antihumanist subject position.6 Moreover, with cubism, temporality—duration—and a multiplicity of points of view became embedded in the picture plane.

With North American experimental (or structural) film in the 1960s and 1970s, notably influenced by Andy Warhol’s filmic work, duration became a key component of aesthetic experience, grounded in an exploration of the filmic apparatus and seeking to make it analogous to human consciousness. By creating cinematic equivalents or metaphors of consciousness, experimental film brought about a prosthetic vision giving way to solipsistic visual experiences.7 A futuristic technoscape, Michael Snow’s experimental film La Région centrale (1971) is exemplary in this regard. In the film (as in all of his work), Snow explores the genetic properties of the filmic apparatus, using it to intensify and diminish aspects of normal vision. La Région centrale shows images from the wilderness collected by a machine specifically designed to shoot the film (De La). The machine was able to move in all directions, turn around 360 degrees, and zoom in and out, reaching places no human eye could perceive before. The resulting footage was independent of any human decisions and framing vision: a three-and-a-half hour topological exploration of the wilderness, a “gigantic landscape.”8

Because De La extracts gravity from the situation as well as human (preconstructed or given) referential points of view, La Région hypostazises the cubist relativization of identity and difference and its rejection of a priori space. Furthermore, the film puts forth an experience of matter within, decentering the subject, which is constituted by the experience of the work itself. To paraphrase Rosalind Krauss on minimalism, the film subverts the notion of a stable structure that could mirror the viewer’s own self—a self that is completely constituted prior to experience. That is to say, the film formulates a notion of self that exists only at the moment of externality of that particular experience.9 By presenting every possible position of the framing-camera in relationship to itself, La Région releases the subject from its human coordinates, creating a “space without reference points where the ground and the sky, the horizontal and the vertical inter-exchange.”10 The references to human coordinates are the screen’s rectangular frame and the breaks made by the intermittent appearance of a big glowing yellow “X” against a black screen. Every time the X comes up, it fixes the screen and transfers the movement in a different way or direction; thus, the Xs are the point of view embodying the apprehension of the passage from chaos to form. In viewing the film, the present is experienced as immediacy, a pure phenomenological consciousness without the contamination of historical or a priori meaning; the world is thus experienced as self-sufficient, pure presence, foregrounding an awareness of the presence of the viewer’s own perceptual processes. As Snow stated:

My films are experiences: real experiences … The structure is obviously important, and one describes it because it’s more easily describable than other aspects, but the shape, with all the other elements, adds up to something which can’t be said verbally and that’s why the work is, why it exists.11

In general, experimental film sought to posit alternatives to the mimetical inscription of lived experience into simulacral images (signs) by artistic neovanguardist practices that came to be embedded within the logic of spectacle—not in order to dislodge subjectivity (early modernism) or to constitute subjects by mapping out signs (postmodernism), but by exploring through film the conditions of cognition and perception. And while there is something in the image delivered by La Région that shares something with the condition of thought, it yields a solipsistic subject at the genetic level of perception; beyond auditory or optical perceptions, it delivers motor-sensory perceptions.12 Therefore, the machine delivers a posthuman, prosthetic enhancement of vision, inaugurating three important developments in the history of perception.

First, the machine introduces the incipient normalization of perception as augmented reality and the solipsistic visualization of data. Second, as Donna Haraway posited, the prosthetic enhancement of vision brings about the notion of limitlessness and an “unregulated gluttony” that desires to see everything from nowhere, spreading the assumption that anything can and is seen.13 Third, with La Région, machinic vision becomes an epistemological product of a centered human point of view (with the Xs) without stable reference points, foregrounding the conditions of contemporary visuality. While cubism embodies the antihumanist scission of the subject and the possibility of the construction of many psychical planes, La Région embodies the displacement of the human agent from the subjective center of operations.14 Both epitomize modernity’s fragmentation by mechanization, its alienating character, its inability to give back an image or to serve as a reflective mirror—it can never do this because the antihumanist image is indifferent to me.15 And yet, this was always going to be the fate of an image and of art based on contemplation. These works also attest to the fact that the foundational experience of modernity is to refuse, in advance, the “given” as a ground for thought.16

The Transformation of Everything into Data-Images

As previously explained, the Anthropocene era implies not a new image of the world, but the transformation of the world into images. Humanity’s alteration of the biophysical systems of earth is parallel to the rapid modifications of the receptive fields of the human visual cortex announced by cubism and experimental film. This alteration is also accompanied by an unprecedented explosion in the circulation of visibilities, which are actually making the outcome of these alterations opaque.17 For instance, the exhaustive visualization and documentation of wildlife is actually rendering its ongoing extinction invisible. Aside from having become shields against reality, images are not only substitutes for first-hand experience, but have also become certifiers of reality, and, as Susan Sontag points out, they have extraordinary powers to determine our demands on reality.18 In discussing the democratization of tourism in the 1970s, Sontag further described tourists’ dependence of photographic cameras for making real their experiences abroad:

Taking photographs … is a way of certifying experience, [but] also a way of refusing it—by limiting experience to a search for the photogenic, by converting experience into an image, a souvenir … The very activity of taking pictures is soothing, and assuages general feelings of disorientation that are likely to be exacerbated by travel.19

Almost forty years later, posing for, taking, sharing, liking, forwarding, and looking at images are actions that are not only integral to tourism; they actually give shape to contemporary experience. Arguably, representation has ceased to exist in plain view and manifests itself as experience, event, or the appropriation and sharing of a mediatic space. Instead of representation, we have media objects (i.e., a twitterbot) that purport to provide vague participatory representational events that ground our cultural and social experience. Thus, as Stephen Shaviro points out, in the contemporary world, the opposition between reality-based and image-based modes of presentation breaks down, and the most intense and vivid reality is precisely the reality of images.20

In other words, images have in themselves become opaque cognitive and empirical experiences. Each episode of the recent British science-fiction television series Black Mirror explores the implications of this precise phenomena—of images becoming not only an intrinsic part of our empirical experience but also our cognitive experience at large. The “black mirror,” then, is nothing other than the LCD screen through which we give shape to reality.

One of the show’s early episodes, “The Entire History of You” (2011), imagines a world in which almost everyone has a “grain” implanted behind their ear. This grain has the capacity to transform human eyes into cameras that record reality and projectors that can reproduce it, thereby amalgamating lived experience, memory, and image. In a later episode, “Be Right Back” (2013), a woman is able to revive her dead partner with a program that rebuilds him—first his writing habits, then speech patterns, and eventually his very self via a cloned, synthetic body—solely from the proliferation of information he uploaded on the internet when he was alive. The deathless and bodiless information, images, and signs—the inert map of a life—becomes embodied by an avatar that exists in actual, not virtual, reality, and that has the (albeit limited) capacity to exist and interact directly with humans. In the episode, the fabrication of subjectivity from data—which implies the automatization of subjectivity—foreshadows the relationship between determinist automatisms and cognitive activity, which, according to Franco Berardi, is the core goal of the Google Empire: to capture user attention and to translate our cognitive acts into automatic sequences. The consequence is the replacement of cognition by a chain of automated connections, seeking to automatize the subjectivities of users.21

Aside from the fact that images and data are taking the place of or giving form to experience, automating our will and thought, they are also transforming things into signs by welding together image and discourse, bringing about a tautological form of vision. With the widespread use of photography and digital imaging, all signs begin to lead to other signs, prompted by the desire to see and to know, to document and to archive information. Thus the fantasy that everything is or can be made visible coexists with the increasing automation of cognition, which, following Franco Berardi, is the basic condition of semiocapital (the valorization and accumulation of signs as economic assets).22

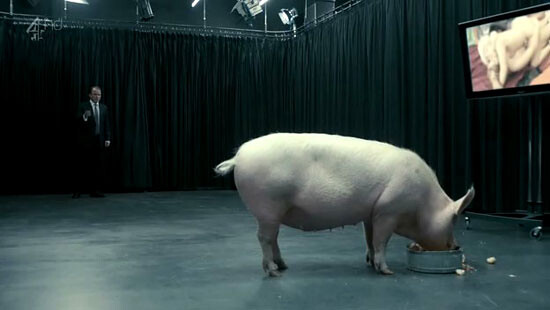

In the pilot episode of Black Mirror, “The National Anthem” (2011), an alleged terrorist group kidnaps a nationally beloved British princess in the early morning hours. In order to free her, the anonymous group demands that the prime minister have sex on live television with a pig at four o’clock that same afternoon. The video in which the princess announces the “price” of the ransom goes viral and the whole nation pressures the prime minister to fulfill the kidnappers’ demands. At the end of the episode, postcoitus, it is revealed that the kidnapping was a singular artist’s gesture, intended in its successful implementation to point critically to the obscenely inflated role the media has in shaping public opinion and official policy. The artist’s action, in other words, illuminates the highly visceral shift in power brought on almost instantaneously by the ransom video’s circulation in the infosphere. Insofar as the episode unfolds montages of the whole nation glued to televisions in the pub, workplace, and waiting room at four o’clock, the artist highlights how connective interfaces actually govern, as they have the direct capacity to manipulate and coordinate behavior on almost every level.23

Under the conditions of semiocapitalism, images and signs acquire value and/or power by means of being seen, largely through “likes” and retweets. The fact that sign-value has supplanted exchange-value means moreover that we no longer consume material things, but rather swallow cognitive signs embedded in and around them. Aside from consuming “experiences” or “moods,” we buy immaterial commodities (in the name of lifestyle and branding) and consume signs for “equality,” “happiness,” “wellness,” and “fulfillment.” In Don Delillo’s White Noise (1985), Jack Gladney describes a trip to the supermarket and makes clear how the signs found in the brands and labels of products that he and his wife buy have the power to relieve them of the mysteries and anxieties brought about by everyday life:

It seemed to me that Babette and I, in the mass and variety of our purchases, in the sheer plenitude those crowded bags suggested, the weight and size and number, the familiar package designs and vivid lettering, the giant sizes, the family bargain packs with Day-Glo sale stickers, in the sense of replenishment we felt, the sense of well-being, the security and contentment these products brought to some snug home in our souls—it seemed we had achieved a fullness of being that is not known to people who need less, expect less, who plan their lives around lonely walks in the evening.24

What becomes evident in this paragraph is Baudrillard’s assertion that objects are no longer commodities whose message and meaning we can appropriate and decipher, but rather, tests that interrogate us. For him, commodities are a referendum, the verification of a code, circularity as well as sameness and homogeneity: here the commodities bring a well-being that reflects the well-being of the consumer and his or her lifestyle.25 Furthermore, the acceleration in proliferation of cognitive signs since the time of Delillo’s novel is another of the features of communicative capitalism’s subjugation, submitting the mind to an ever-increasing pace of perceptual stimuli, and in so doing generating not only panic and anxiety, but also destroying all possible forms of autonomous subjectivation.26 Under communicative capitalism, images transformed into signs embody the current concatenation of knowledge and machines—that is, the technological organization of capitalism to produce value. With the enabling of the visualization of data by machines, images have become scientific, managerial, and military instruments of knowledge, and thus of capital and power.27 In this context, seeing means the accelerating perception of the fields of everyday experiences, or rather, the field of trivial visual analogies of experience: a kind of groundless, accelerated tautological vision derived from passive observation. This is for Berardi another of communicative capitalism’s forms of governance, as this kind of vision generates technolinguistic automatisms by carrying information without meaning, automating thought and the will.28

Images as Cognition and thus Forms of Power

Images circulating in the infosphere are also charged with affect, exposing the viewer to sensations that go beyond everyday perception. Hollywood cinema, for instance, delivers pure sensation and intensities that have no meaning. In Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity (2013), the main characters try to survive in outer space by solving practical and technical problems. The movie repudiates a point of view and a ground for vision in favor of immersion, transforming images into physical sensations mobilized by the visual and auditory (especially in its 3-D version), and thus into affect. The becoming-affect of images derives from communicative capitalism’s ruthless conversion of sensation and aesthetic experiences into cognition: its transformation of these experiences into information, sensations, and intensities without meaning is precisely what enables them to be exploited as forms of work and sold as new experiences and exciting lifestyle choices.29 One of the problems that arises is that affect cannot be linked to a larger network of identity and meaning. Gravity also presents itself as a symptom of the normalization of a groundless seeing brought about by modernity’s decentering of the subject parallel to our exposure to aerial images (for example, Google Earth). The hegemonic sight convention of visuality is an empowered, unstable, free-falling, and floating bird’s eye view that mirrors the present moment’s ubiquitous condition of groundlessness.30

According to many thinkers, this groundlessness characterizes the Anthropocene. The current fragmentation and transience of sociopolitical movements attests to the fact that we are first of all lacking ground on which to found politics, our social lives, and our relationship to the environment. Second, as Claire Colebrook put it, with the Anthropocene we are facing human extinction, as well as causing other extinctions, thereby annihilating that which makes us human. We are thus all thrown into a situation of urgent interconnectedness, in which a complex multiplicity of diverging forces and timelines that exceed any manageable point of view converge.31 In this context, criticality is both in trouble and spinning on its head. Many questions arise: How do we redefine the ground of deterritorialized subjectivation beyond the subsumption of subjectivity by the modes of governance of accelerated tautological forms of vision and communicative capitalism? How can we transform our relationship to the indeterminacy of deterritorialization and the multiplicity of diverging points of view in order to provide a heightened sense of place, giving way to the possibility of collective autonomous subjectivation and thus a new sense of politics and of the image?

In an era of ubiquitous synthetic and digital images dissociated from human vision and directly tied to power and capital, when images and aesthetic experience have been turned into cognition and thus into empty sensations or tautological truths about reality, the image of the Anthropocene is yet to come. The Anthropocene is “the age of man” that announces its own extinction. In other words, the Anthropocene thesis posits “man” as the end of its own destiny. Therefore, while the Anthropocene narrative keeps “man” at its very center, it marks the death of the posthuman and of antihumanism, because there can be no redeeming critical antihumanist or posthuman figure in which either metaphysics or technological and scientific advances would find a way to reconcile human life with ecology. In short, images of the Anthropocene are missing. Thus, it is necessary to transcend our incapacity to imagine an alternative or something better. We can first do this: draw a distinction between images and imagery, or pictures. Although it is related to the optic nerve, the picture does not make an image.32 In order to make images, it is necessary to make vision assassinate perception; it is necessary to ground vision, and then perform (as in artistic activity) and think vision (as in critical activity).33

Images to Come

Following Jean-Luc Godard, who operates in his work between the registers of the real, the imaginary, and art, only cinema is capable of delivering images as opposed to imagery, conveying not a subject but the supposition of the subject and thus the verb (substance).34 Alterity is absolutely necessary for the image, as the image is an intensification of presence—this is why it is able to hold out against all experiences of vision.35 In this light,Godard’s cinematic project can be interpreted as a conception of the image as a promise of flesh. For Godard, the image is incertitude, it is “trying to see” and the possibility of “giving voices back to their bodies.” For the filmmaker, images do not show; rather, images are a matter of belief and a desire to see (which is different from the desire to know or to possess).

An essay-film Godard made with Anne-Marie Miéville, The Old Place (2001), addresses the Anthropocenic concerns of life after the extinction of man, the current groundlessness of vision, and the lack of images of the world and of humanity. While we see images from outer space, Miéville and Godard discuss “CLIO,” the archaeological bird of the future, a microsatellite sent into space in 2001. The satellite is supposed to come back to earth in five thousand years to inform its future inhabitants about the past. Aside from carrying traditional human forms of knowledge, the bird will deliver messages written by the current inhabitants of the globe addressed to its future inhabitants. Miéville and Godard ponder whether humanist messages such as “Love each other,” or “Eliminate discrimination against women,” will be included in the satellite (they doubt it). Later on, they conclude:

We are all lost in the immensity of the universe and in the depth of our own spirit. There is no way back home, there is no home. The human species has blown up and dispersed in the stars. We can neither deal with the past nor with the present, and the future takes us more and more away from the concept of home. We are not free, as we like to think, but lost.

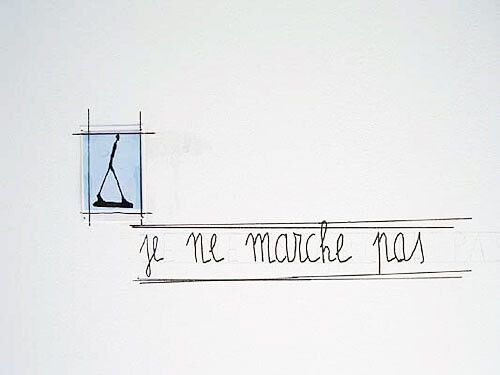

Here Godard and Miéville paint the termination of a world, its exhaustion and estrangement from its conditions of possibility. As they underscore the lack of a home for the spirit, they highlight the loss of a sense of origin and destination, implying that the active principle of the world has ceased to function.36 The last line is spoken while we see the image of a mother polar bear staring at her dead cub, followed by an image of Alberto Giacometti’s sculpture L’homme qui marche (Walking Man, 1961): life persists irrationally, not given form by imagination, ceasing to cohere into a higher truth.37

In The Old Place, Godard and Miéville explore the image of humanity throughout the Western history of art, underscoring the fact that for two thousand Eurocentric, Christian years, the image was sacred. We also see images of violence, torture, and death juxtaposed with beautiful sculpted and painted figures and faces created throughout all the ages of humanity: people by turns smiling, screaming, or crying.

For Godard and Miéville, the image is also something related to the origin that reveals itself as the new but that had been there all along: an originary landscape always present and inextricable from history. Marking the passage to the current regime of communicative capitalism, where images are permeated by discourse and tautological truths about reality, they state: “The image today is not what we see, but what the caption states.” This is the definition of publicity, which they further link to the transformation of art into market and marketing represented by both Andy Warhol, and by the fact that “The last Citroën will be named Picasso,” which has as a consequence that “The spaces of publicity now occupy the spaces of hope.” And yet, in spite of the ubiquity of communicative capitalism, for them there is something that resists, something that remains in art and in the image. Meanwhile, we see a blank canvas held by four mechanical legs moving furiously.38 This evokes the resisting image to come; this resisting image is a question of (sensible, un-automated) purity and, in post-Christian secular sense, of the sacred and redemption, of an ambivalent relationship between image and text, foreign to knowledge and intrinsically tied to belief. At the end of The Old Place, the filmmakers posit the Malay legend of A Bao A Qu as the paradigm of the image of these times in which “we are lost without a home,” as they state. “The text of A Bao A Qu is the illustration of this film.” The legend is rewritten by Jorge Luis Borges in his Book of Imaginary Beings:

To see the most lovely landscape in the world, a traveler must climb the Tower of Victory in Chitor. A winding staircase gives access to the circular terrace on top, but only those who do not believe in the legend dare climb the tower. On the stairway there has lived since the beginning of time a being sensitive to the many shades of the human soul known as A Bao A Qu. It sleeps until the approach of a traveler and some secret life within it begins to glow and its translucent body begins to stir. As the traveler climbs the stairs, the being regains consciousness and follows at the traveler’s heels, becoming more intense in bluish color and coming closer to perfection. But it achieves its ultimate form only at the topmost step, and only when the traveler is one who has already attained Nirvana, whose acts cast no shadows. Otherwise, the being hesitates at the final step and suffers at its inability to achieve perfection. As the traveler climbs back down, it tumbles back to the first step and collapses weary and shapeless, awaiting the approach of the next traveler. It is only possible to see it properly when it has climbed half the steps, as it takes a clear shape when its body stretches out in order to help itself climb up. Those who have seen it, say that it can look with all of its body and that at the touch, it reminds one of a peach’s skin. In the course of the centuries, A Bao A Qu has reached the terrace only once.39

In their film, Godard and Miéville explore the imprint of the quest of what it means to be human throughout the history of images. Humanity transpires as a mark that is perpetually reinscribed in a form of an address. A Bao A Qu is an inhuman thing activated by the passage of humans wishing to see the most beautiful landscape in the world. The act of vision is a unique event, and what delivers the vision of the landscape and of the creature are the purity and desire of the viewer. A Bao A Qu is an image of alterity; it stares back with all of its body. A Bao A Qu is an antidote to the lack of imagination in our times: an inhuman vision that undermines the narrative that holds the human as the central figure of its ultimate form of vision and destruction.

In the voiceover of his most recent film, Adieu au langage (Farewell to Language, 2014), Godard quotes Rilke: “It is not the animal which is blind, but man. Blinded by consciousness, man is incapable of seeing the world.” With a strident palette and saturated sound, the film evokes abstract, fauvist, cubist, and impressionist painting, and is Godard’s most radically experimental film (as in the genre, because all his work is experimental and radical) to date. Rilke’s quote, together with an aphorism he attributes to Monet, frame Godard’s quest in this film: “It is not about seeing what we see, because we do not see anything, but [it is about] painting what we cannot see.” In parallel, Godard revives the romantic poet’s wish to “describe” immediate reality, to hit the viewer with electroshocks that make a real visible and audible world emerge from language. In the film, as a way to enable a new form of communication beyond tautological digital communication (Godard points out that with texting there is neither the chance to interpret a code nor room for ambiguity) and to reestablish harmony between the couple in the movie who can no longer communicate face to face, Roxy Miéville’s dog appears. Roxy becomes the metaphor for the possibility of an “other” post-anthropocentric language “between” humans. In the movie, the dog asks, “What is man? What is a city? What is war?” Rocky’s comings and goings between the couple bear the possibility of giving back freedom to the face-to-face encounter. Godard compare’s Roxy’s “other” language to the lost language of the poor, the excluded, animals, plants, the handicapped—those who are out of the frame. In sum, the movie is a giant mirror that reflects a grammar of thought that no longer resides in enunciation (and this is the farewell to language): marking the absence of a relationship between the characters by using Roxy—the third person, the post-anthropocentric “other”—as a vehicle of communication.

In both The Old Place and Adieu au langage, Godard addresses spectacular modernity’s (semiocapitalism’s) crisis of visuality, which causes a lack of imagination, or even blindness. He also posits alternatives: an inhuman vision beyond a humanist-centered view, a post-anthropocentric “other.” In contrast to post-humanism, the filmic camera and technology are not what enable vision in these films. Rather, vision is enabled by a mythical being (A Bao A Qu) and by Roxy the dog, which, at the end of Adieu, barks in unison with the cry of a newborn baby, announcing the new to come.

Werner Herzog, Herzog on Herzog (New York: Faber and Faber, 2003), 164.

Dominic Fox, Cold World: The Aesthetics of Dejection and the Politics of Militant Dysphoria (London: Zero Books, 2009), 1.

Nick Srnieck and Alex Williams, “#ACCELERATE MANIFESTO for an Accelerationist Politics,” May 14, 2013, par. 23 →.

Stan Brakhage, “From ‘Metaphors on Vision,’” The Avant-Garde Film: A Reader of Theory and Criticism, ed. P. Adams Sitney(New York: Anthology Film Archives, 1978), 120.

Georges Didi-Huberman, “Picture = Rupture: Visual Experience, Form and Symptom According to Carl Einstein,” Papers of Surrealism 7 (2007): 5.

Ibid., 6.

Anthology Film Archives is a theater in New York where in the late sixties and early seventies filmmakers and artists (Snow amongst them) would gather to watch films. At the time, the theater had wing-like chairs that isolated the viewer sensorially in order to “equate” her field of vision to the screen, thereby delivering a solipsistic experience.

Michael Snow, The Michael Snow Project: The Collected Writings of Michael Snow (Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1994), 56.

Krauss, 50.

Gilles Deleuze, Cinema I: The Movement-Image (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986), 84.

Snow, The Michael Snow Project, 44.

Deleuze, Cinema I, 85.

Donna Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective” Feminist Studies, vol. 14, no. 3 (Autumn 1988): 575–99, 582.

Didi-Huberman, “Picture = Rupture,” 9.

Melissa McMahon, “Beauty: Machinic Repetition in the Age of Art,” in A Shock to Thought: Expression After Deleuze and Guattari, ed. Brian Massumi (London: Routledge, 2002), 4.

Ibid., 8.

Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011), 12.

Susan Sontag, On Photography (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977), 80.

Ibid., 177

Stephen Shaviro, “Post-Cinematic Affect: On Grace Jones, Boarding Gate and Southland Tales,” Film Philosophy 14.1 (2010): 12.

Franco “Bifo” Berardi, “The Neuroplastic Dilemma: Consciousness and Evolution,” e-flux journal 60 (Dec. 2014): pars. 21–23 →.

Ibid., par. 3.

Franco “Bifo” Berardi, The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance (New York: Semiotexte, 2012), 15.

Don Delillo, White Noise (New York: Picador, 2002), 20.

Jean Baudrillard,“Toward a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign,” trans. Carl R. Lovitt and Denise Klopsch, SubStance, vol. 5, no. 15 (1976): 111–116.

Franco “Bifo” Berardi, “Accelerationism Questioned from the Point of View of the Body” e-flux journal 46 (June 2013): par. 11 →.

Benjamin Bratton,“Some Trace Effects of the Post-Anthropocene: On Accelerationist Geopolitical Aesthetics,” e-flux journal 46 (June 2013): par. 16 →.

Berardi, The Uprising, 41.

Shaviro, “Post-Cinematic Affect,” par. 14.

Hito Steyerl, “In Free Fall: A Thought Experiment on Vertical Perspective,” e-flux journal 24 (April 2011): par. 6 →.

Claire Colebrook and Cary Wolfe, “Dialogue on the Anthropocene,” Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, Jan. 23, 2013 →.

Serge Daney, “Before and After the Image,” Revue des Études Palestiniennes 40 (Summer 1991): par. 2 →.

Didi-Huberman, “Picture = Rupture,” 17.

Georges Didi-Huberman, “The Supposition of the Aura: The Now, the Then, and Modernity,” Walter Benjamin and History, ed. Andrew Benjamin (New York: Continuum, 2006), 8.

Daney, “Before and After the Image,” par. 2.

Fox, Cold World, 7.

Ibid., 70.

I have been unable to locate the author, title, date and location of this evocative mechanical sculpture.

Jorge Luis Borges, The Book of Imaginary Beings, trans. Andrew Hurley (New York: Viking, 1967), 2.

I would like to thank π who knows why and Romi Mikulinski for her feedback and comments on an earlier version of this essay, which is a chapter from Art in the Anthropocene: Encounters Among Aesthetics, Politics, Environments and Epistemologies, eds. Heather Davis and Etienne Turpin (Ann Arbor: Open Humanities Press, forthcoming 2015).