Sarah Schulman has been a formidable presence in the New York cultural and queer activist milieu for more than thirty years. She has fought for abortion rights, for women’s reproductive health, for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer rights, and against the AIDS crisis. In addition to participating in action in the streets, Schulman has also published numerous novels, plays, screenplays, and nonfiction books. In these works, Schulman has chronicled her experiences and the politics of her various communities in sensuous and candid detail.

The impact and reception of Schulman’s work, however, has always been controversial. From her claims that the content of the successful 1996 musical Rent was lifted from her novel People In Trouble (1991) to her oft-cited difficulty publishing on politically volatile themes like intergenerational gay relationships and the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians, controversy is never far behind her. In the face of such circumstances, Schulman remains a prolific writer and committed political agitator. Despite the systemic exclusion of lesbian and queer writers from most mainstream publishing houses and the political exclusion she has faced from the politically atrophying queer community, she continues to demand accountability of both.

I talked with Schulman, Distinguished Professor of the Humanities at the City University of New York, about her two most recently published nonfiction books, The Gentrification of the Mind (2012) and Israel/Palestine and the Queer International (2012). We discussed queer collaborations, the rapidly changing publishing industry, queer mentorship, and the politics of always coming from the margins.

—Ryan Conrad

Ryan Conrad: Do you feel that there is something particularly queer about collaboration as a mode of art-making and political organizing? Together you and Jim Hubbard are responsible for some amazing projects, including the founding of what is now called the MIXNYC Queer Experimental Film Festival and the ACT UP Oral History Project. You two also coproduced the HIV/AIDS activism documentary United in Anger (2012). Can you talk a little bit about your ongoing investments in film and video and how you and Jim came to collaborate on so many large multi-year projects?

Sarah Schulman: Jim and I have been collaborators for twenty-seven years. I love Jim and we are mutually accountable people with a lot of follow-through and resonant values. I have collaborated with people all my life in one-on-one, small group, and large community settings, but I honestly don’t have any ideology behind it. It wasn’t a conscious decision. Jim is a filmmaker, and back in 1987 when we cofounded MIX, I was dating a filmmaker. We saw that experimental cinema was a natural match for queer audiences because our lives had no known form. Straight people had conventional narrative: romance, marriage, motherhood—but we had formal invention. At the same time, we saw that the experimental film world was homophobic and could not integrate most queer work. The few gay film festivals did not understand experimental. So the natural introduction of experimental into the broadly based, multi-class queer community made perfect sense. We cocurated the festival for seven years and then did the unheard of thing of handing over a fiscally and emotionally healthy organization to younger people, in this case, young curators of color—most notable Rajendra Roy, who is now film curator at MoMA, and Shari Frilot, now at Sundance. Today, MIX is lovingly run by Artistic Director Steven Kent Jusick and its programming committee, board, and volunteers.

RC: You and Jim are among what feels like very few role models for younger generations of queer artists and activists like myself. What excites and keeps you motivated to be part of more radical artistic and political projects over the long haul? Growing older and staying radical is something I think about often, as I’ve just turned thirty. For me, there weren’t many older queer role models out there who stayed radical and hadn’t either died during the AIDS crisis or dropped out of public view.

SS: One of the advantages of being in a cultural vanguard is that we are constantly defining our own terms, creating new community-based institutions, and having the joy of discovery that comes with breaking new ground. These kinds of activities attract the best people. I am constantly surrounded by great young people who are doing wonderful and exciting things with their open hearts and minds. It’s a real blast of life. I am almost always interested in being part of the world, engaging, thinking, listening, and doing. That’s the way I like to live.

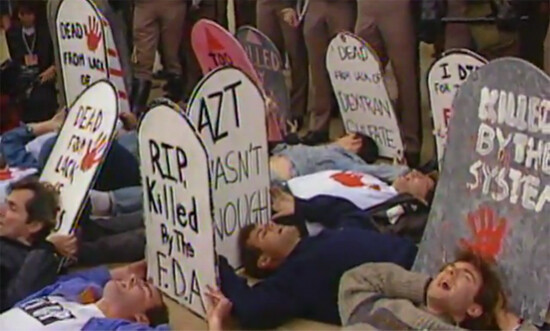

RC: One of your most recent projects was coproducing the documentary film about ACT UP called United in Anger (2012). This documentary, which combines archival footage, commentary, and excerpts from the ACT UP Oral History Project, will serve as a great popular education tool for future generations. What has the response to the film been like?

SS: The film argues that ACT UP was successful because of multiple communities acting in their own ways, simultaneously, which created a zeitgeist for change. We show a range of significant actions and campaigns, from forcing fast track for drug testing at the Food and Drug Administration, to the invention of video activism, to interrupting mass at Saint Patrick’s Cathedral when the Catholic Church got on public school boards to stop condom distribution, to ACT UP’s four-year campaign to get benefits and testing for women with AIDS. We included homeless people fighting for AIDS housing, poor women, women of color, drug users marching in the streets for treatment, and many other overlapping kinds of people and actions. This message appeals enormously to grassroots communities around the world because everywhere people want change, and the film is clear that it is possible for them to create it. We have shown the film in Brazil, all over Europe, and in the United States. Our international premiere was in Palestine and I am on my way to show the film in Abu Dhabi and Beirut. The only sector that has not responded to the film is the corporate sector. They have favored a different film, How to Survive a Plague (2012), which argues that a handful of white individuals working with pharmaceutical companies transformed the AIDS crisis. Corporate media loves individual white heroes and hates the idea of coalitions across class and race. Unfortunately, that mythic, nonexistent story does not work to create change, and anyone who tries to model it will not get very far. It is the critical mass that actually transforms paradigms.

RC: As a younger queer who didn’t live through the ‘80s and ‘90s as an adult, I take the content of these kinds of historiographical projects very seriously. They are among the few ways younger generations can learn more radical queer histories and make sense of the massive loss of life during the worst of the AIDS crisis. Watching David France’s film How to Survive a Plague, I couldn’t help but feel like everything I taught myself about ACT UP over the last decade was wrong, or at least that France’s film only told a very small and partial story about treatment activism within ACT UP, without really framing it as only part of the story. I was squirming in my seat as pharmaceutical representatives were uncritically given airtime throughout the second half of the film. Former ACT UP and Gran Fury member Avram Finkelstein pointed out in a December 2012 article entitled “AIDS 2.0” that “it’s likely we’re now witnessing the solidification of the history of AIDS. It would be bad if it were an incomplete one.”1 To say the stakes are high in how we frame our own histories in films like How to Survive a Plague and United in Anger is an understatement, isn’t it?

SS: The highest. If AIDS activism is historicized as the activities of white individuals cooperating with pharmaceutical machines, then not only will more lies be in place, but communities receiving this information will be deceived about how political transformation actually works. It’s a crippling piece of propaganda.

RC: But I also wonder how projects like United in Anger or your 2012 AIDS memoir The Gentrification of the Mind might encourage or inhibit activism in the present with their backwards-looking stance? Queer scholar Heather Love describes the necessity of looking back on queer history, but also warns against the ways queer histories of trauma and loss can be problematically recuperated, romanticized, or totalized into a disingenuous linear narrative of progress.

SS: These are two different projects. United in Anger was directed by Jim Hubbard to help audiences today understand how change is made and to show that regular people can transform the world. It is an organizing tool that looks forward by showing the contemporary audience not what to do, but how successful tactics are developed. The Gentrification of the Mind is about understanding the consequence of experience. Hopefully, it models a kind of awareness, a desire to understand, but this book is not a primer for change.

RC: How might either project fall into the trap of nostalgia? In the introduction to The Gentrification of the Mind, for example, you don’t respond too kindly to some seemingly naive younger queers who are unaware of older queer artists. There is a bit of a “back in the good old days” tone. Perhaps as one of those younger queers myself, I’m sensitive to how this gap in knowledge is articulated by people who experienced the AIDS crisis first hand. I think a lot about all the ways I had to struggle, with very little help or resources, to learn my own queer histories, especially as a small-town fag.

SS: I don’t agree that these works are nostalgic. The historic cataclysm of the mass death experience of AIDS—among its many consequences—facilitated the transformation of the Gay Liberation movement into the Gay Rights movement. In my book Stagestruck: Theater, AIDS, and The Marketing of Gay America (1998) I showed how an earlier stage of this diminishment was the transformation of a political movement into a consumer group, a niche market for advertisers. By the time I wrote The Gentrification of the Mind in 2012, it was clear to me that the goal of changing society has been replaced by society changing us. The outcome of this change is that queer people are tolerated only to the degree that we reflect dominant cultural values. Awareness and consciousness of these trajectories is essential to understanding why we are where we are. It is true that we live in a culture that falsely naturalizes events. When gentrification first started, we were told that it was a natural evolution. Now we understand that it was a deliberate policy. The global AIDS crisis was also constructed. It was a product of fifteen years of indifference and neglect by the US government and private pharmaceutical companies, an indifference that was only overturned through activism. There are material histories that produce our contemporary moments, and without understanding them we can’t see ourselves.

RC: Could you talk a little bit about why you decided to write The Gentrification of the Mind and Israel/Palestine and the Queer International as memoirs? Both books are first-person historical narratives. What does this style of writing accomplish that other modes of writing cannot? Do you see limits in working in the genre of memoir?

SS: I don’t consider Israel/Palestine to be a memoir. I was forced to call The Gentrification of the Mind a memoir because one of the readers at University of California Press wanted to block the book based on my pro-Palestinian views. University presses have this undesirable system where anonymous “readers,” chosen by the press, can block or censor passages or even entire books without having to discuss the issue with the writer or reveal their identities. In this case, she made many phony criticisms designed to repress any criticism of Israel. To avoid having the book blocked, I had to take out a chapter and call the book a “memoir” to avoid her charge that it was an improper publication for an academic press.

RC: If not memoir, what style of writing would you call these two books? I ask this because I think it’s interesting that both of your books were published by academic presses (Duke University Press and University of California Press) while neither of these books are particularly scholarly.

SS: I call them “nonfiction.” The publishing venues have to do with conglomerations in corporate publishing that push books that would, at one point in US history, be published by mainstream presses to smaller presses. For example, Lesbian Nation by Jill Johnson was published by Simon & Schuster in 1973. Now many of these kinds of books are published by university presses, which in turn makes it harder for non-academic nonfiction books to get published.

RC: In your newest book, Israel/Palestine and the Queer International, I can’t help but notice how generously vulnerable you make yourself throughout the text. The book focuses largely on your own personal journey, as a diasporic New York Jew, to understand the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians. You come to feel that you have an ethical responsibility to fight injustice perpetrated by the Israeli government against Palestinians. In the first half of the text, you acknowledge that you knew little about the politics of the struggle there, and you discuss all sorts of difficult and uncomfortable feelings you had while working through this issue. Can you talk about how it feels to have this very personal book published, a book that reveals a lot about you and your family history? How have people responded?

SS: I don’t think it really registers as vulnerable or even personal, just as true, or as trying to know what is true. I have been talking and writing conversationally all of my life, or at least it feels that way, so the book’s tone feels natural and consistent. In terms of reader response, I find that there have been two sets of reactions: interested Jews, queers, and others get a lot out of the book, since it takes something that they have been told is “very complicated” and makes it available for consideration. On the other hand, the reaction of fanatically right-wing Jews has been pretty pathological. Comments have ranged from “She should be raped by Muslims” to “This freak deserves a Rachel Corie moment” to being called “The face of self-hating Jewry.” And of course, the NYC LGBT Center banned me from doing a reading from the book. Meanwhile, the straight mainstream has entirely ignored the book. From Frank Rich to The Nation to The New York Review of Books, The New Yorker, The New York Times and NPR—it remains entirely ignored.

RC: The threat of rape and death seems to occur when any of us from the margins stick our necks out to demand political accountability. As cofounders of the Against Equality Collective—an online archive, publishing, and arts collective committed to challenging mainstream gay and lesbian organizations’ demand for inclusion in the institution of marriage, the US military, and the prison industrial complex via hate crimes legislation—Yasmin Nair and I have also received pretty graphic and detailed death threats. And these threats came from other gay people no less! In one of the chapters in Israel/Palestine and the Queer International, you detail the rather pathetic process through which the NYC LGBT Center created the ban that prevented groups organizing around the Israel/Palestine issue from meeting there. You even note that you weren’t able to screen a queer film related to the Israel/Palestine issue at the Center after the ban was put in place. When you tried to organize a reading there, you must have known it would not be accepted. Based on your writing and your activist history, it seems that you’re a pretty savvy political organizer, so I imagine your book reading was part of a political strategy to provoke dialogue and challenge the Center on the issue. Was this the case?

SS: Actually, I did not know that it would be rejected. Quite some time had passed since the ban was put in place and my request was as conventional as could be. I was asking to read from a book that had the word “queer” in the title and that was published by reputable publisher. It was a pretty nerdy request. I thought that they might be ready to ease into reason.

RC: Your book also has the words “Israel/Palestine” in the title, which is clearly something the Center had a policy banning, as described at length in your chapter “Backlash.” I’m surprised to hear that your decision to read there wasn’t politically strategic, when there is an entire chapter in your book on “Finding the Strategy.” Your proposed book reading and its subsequent rejection by the Center, which caused great uproar and actually forced the center to reevaluate its position on the matter, all happened sort of accidentally?

SS: New York Queers Against Israeli Apartheid (NYC-QAIA) asked me if I would let them propose a reading from my new book at the LGBT Center. I said yes. I felt it would be ridiculous for the Center to ban me from reading from a book on queer politics published by Duke University Press. I didn’t think they would be that completely out of it, or at least I hoped they wouldn’t. But they were. Fortunately, Tom Léger—a brilliant activist and the publisher at Topside Press—immediately put up a petition that automatically sent an email to Glennda Testone, the director of the Center, for each person that signed. Within two days she received a thousand emails. I was out of the country touring with United in Anger at the time and didn’t even know he was doing this. Jim and I are going to Beirut soon, where I am giving the exact same talk that was banned at the Center. Crazy, right?

RC: I think it’s pretty great that the proposal that you read at the LGBT Center has really helped push the issue there. From what I’ve read though, ever-vigilant opportunists like New York City mayoral candidate Christine Quinn have swooped in to praise the Center’s new “hate speech guidelines,” which seem a bit vague if not rather dubious.2 It will be interesting to see what happens in the future considering you still don’t have a date for your reading and the Center has a history of trying to ignore people until they go away.

SS: Quinn used to be a cut dyke when she was young. We got arrested together protesting Irish queers being excluded from the St. Patrick’s Day Parade in New York City. But she is on the wrong side of free speech because Stuart Appelbaum, a gay labor leader who supports current Israeli state policies, was her first big endorsement for mayor. He fed her language coming right from the Israeli Prime Minister’s office claiming that supporting a nonviolent boycott, divestment, and sanctions movement is “hate speech.”3 The Israeli government has tried this in Israel and in Toronto and now she is their dupe for trying it here.4 It’s vulgar anti-constitutional politics.

RC: It seems like Quinn has been on the wrong side of many issues since she gained institutional power through becoming a City Councilor in New York.5 She was the central focus for the now defunct theatrical queer activist group The Radical Homosexual Agenda. I imagine the mayoral race in New York City this year is going to be really interesting for queer New Yorkers. Speaking of the future, can you tell me a little more about what projects you have in the works and how you plan to continue building towards the queer international?

SS: Right now I am organizing both the Homonationalism and Pinkwashing Conference at CUNY in April and the first Palestinian Writers panel at The PEN Global Visions Conference in May. I will be teaching at the Lambda Literary Emerging Writers Retreat in Los Angeles in July as well as at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown in August. I’m also collaborating on three movies and have a play reading at both the New York Theater Workshop in April and the Trinity Repertory in May. I also have a new novel for sale called The Cosmopolitans. I wanted it to sound like a Henry James book. It is a rethinking of French novelist Honoré de Balzac’s Cousin Bette (1846). It is set in New York City in 1958 and for that reason it evolves into an answer book to James Baldwin’s Another Country. It’s set in that same bohemian milieu, with interracial and mixed sexualities, but this time the women are real.